Travel

Travel  Travel

Travel  Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

20 Examples of Why You Should Enjoy Poetry

Here is a sampler of various English-language poetry which, I hope, will give non-readers of poetry, in particular, the impetus to follow through and discover the joys of poetry for themselves.

The samples I have included are representative of the development of poetry over some 800 years, but without going into technical or critical detail; that is to say, I have tried to provide examples that may, notwithstanding any deeper meaning, be appreciated at face value.

Note that the list is fairly traditional, in that there are no examples of ethnic verse. This is purely for the reason that I have limited my selections to works with which I am familiar (ie. largely British and, to a lesser extent, American). It was extremely difficult restricting the list to the 20 excerpts detailed below and, whilst literary merit was my primary criteria, (arguably) my one indulgence was the William Carlos Williams poem.

If your own favourite is not here, tell us about it.

Lhude sing cuccu!

Groweth sed and bloweth med,

And springeth the wude nu –

Sing cuccu!

Awe bleteth after lomb,

Lhouth after calve cu;

Bulluc sterteth, bucke verteth,

Murie sing cuccu!

[Loose translation]

Summer has arrived,

Sing loudly, Cuckoo!

Seeds grow and meadows bloom

And the forest springs anew

The ewe bleats after the lamb,

The cow lows after the calf.

The bullock leaps, the buck farts,

Sing merrily, Cuckoo!

This wonderful lyric is one of the most famous examples of Middle English (1066-1450) and, although it was traditionally sung as a “round”, is also commonly taught as an introduction to Middle English literature. It is thought to be written in the Wessex Dialect. W. de Wycombe, a late 13th century English composer and copyist has been suggested as being the author, but there is little evidence to support this. It is typically attributed as Anonymous.

Note that a round is a musical piece in which two or more voices repeatedly sing the same melody, but with each voice starting at a different time. “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” is an example of a round that most people will be familiar with.

Interesting fact: whilst some commentators translate verteth as “twisting” (or whatever) the word is, in fact, the earliest written example of vert, the Middle English version of fart!

And here is a very nice choral version for your listening pleasure, in counterpoint.

Image: Shakespeare’s First Folio, 1623

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Shakespeare who? A great sonnet from the nonpareil!

Interesting fact: Shakespeare ultimately had no descendents – apparently, his grandchildren all died!

Before rude hands have touch’d it?

Have you mark’d but the fall of the snow

Before the soil hath smutch’d it?

Have you felt the wool of beaver,

Or swan’s down ever?

Or have smelt o’ the bud o’ the brier,

Or the nard in the fire?

Or have tasted the bag of the bee?

O so white, O so soft, O so sweet is she!

I was so tempted to quote Jonson’s famous Song : To Celia, which includes the famous line “Drink to me only with thine eyes”, but this lesser known example of his work is typical of his lyricism. It was published as one of ten linked pieces in 1623. A friend of William Shakespeare, Jonson was a complex character; he apparently liked an argument and could be arrogant, but was also noted for his sense of honour and integrity. Not quite a genius…but still one of the giants of English literature.

Interesting fact: Jonson is the only person buried standing up in Westminster Abbey (London). His grave bears the famous epitaph “O Rare Ben Johnson” – yes, the inscription erroneously includes an “h” in his name – the engraver made a mistake!

According to Westminster Abbey:

In 1849, the place was disturbed by a burial nearby and the clerk of works saw the two leg bones of Jonson fixed upright in the sand and the skull came rolling down from a position above the leg bones into the newly made grave. There was still some red hair attached to it.

Entire of itself.

Each is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less.

As well as if a promontory were.

As well as if a manor of thine own

Or of thine friend’s were.

Each man’s death diminishes me,

For I am involved in mankind.

Therefore, send not to know

For whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.

These famous words by John Donne (pronounced “Dunn”) were not originally written as a poem – the passage is taken from the 1624 Meditation 17, from Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions and is prose. The final 3 lines are possibly amongst the most quoted excerpts of English verse.

Interesting fact: Donne was Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral (London)

Old Times is still a-flying:

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.

Born in London’s Cheapside, Herrick was the seventh child and fourth son of Nicholas Herrick, a prosperous goldsmith, who committed suicide when Robert was a year old. He ultimately took religious orders, and became vicar of the parish of Dean Prior, Devon in 1629, a post that carried a term of thirty-one years. It was in the secluded country life of Devon that he wrote some of his best work.

The over-riding message of Herrick’s work is that life is short, the world is beautiful, love is splendid, and we must use the short time we have to make the most of it (“carpe diem”). He is also renowned for frequent references to lovemaking and the female body.

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage;

If I have freedom in my love,

And in my soul am free,

Angels alone that soar above

Enjoy such liberty.

Richard Lovelace was born a nobleman, being the firstborn son of a knight. On April 30, 1642, on behalf of Royalists in Kent, he presented to Parliament a petition asking them to restore the Anglican bishops to Parliament; as a result he was immediately imprisoned in Westminster Gatehouse where, whilst serving his time, wrote “To Althea, From Prison”, which contains – as per the excerpt given – one of the more famed lines of English verse “Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage”. Basically, Lovelace is saying that physical imprisonment/oppression cannot stifle his imagination or spirit.

Interesting fact: While in prison, Lovelace worked on a volume of poems, titled Lucasta, which was considered to be his best collection. The “Lucasta” to whom he dedicated much of his verse was Lucy Sacheverell, whom he often called Lux Casta. Unfortunately, she mistakenly believed that he died at the Battle of Dunkirk in 1646 and so married somebody else. Oops!

Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that, on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd who first taught the chosen seed

In the beginning how the Heav’ns and Earth

Rose out of Chaos;

Milton ! Another literary giant. Possibly ranked, in terms of sheer literary genius, second to Shakespeare. Paradise Lost is an epic, dealing with the fall and subsequent salvation of Man. So great was the contemporary acclaim for Milton’s poetic epics, that other writers began to avoid writing long poetical works…which contributed to the birth of the novel as a literary genre.

Interesting fact: Milton became blind, and most of his prodigious works were dictated to a secretary.

Also: as a student at Cambridge University, Milton was so vain about his appearance that he was nicknamed “the Lady of Christ’s College”.

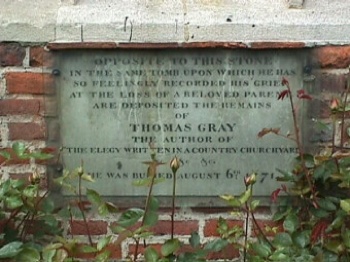

Image: Inscription on the Church at Stoke Poges refering to Gray’s Elegy

The lowing Herd winds slowly o’er the Lea,

The Plowman homeward plods his weary Way,

And leaves the World to Darkness, and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

?And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

?Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

?And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds.

Gray’s Elegy (an elegy commemorates death) was written after the passing of one of Gray’s close friends, and is a meditation on the mortality of man. Gray was Professor of History and Modern Languages at Cambridge and, despite not being a prolific writer, was one of the most prominent poets of his day He was buried in Stoke Poges (near Windsor, England) the village whose churchyard was where he composed the Elegy.

Interesting fact: although he became a literary giant of his age, Gray only published 1,000 lines of poetry during his lifetime – this was due, largely, to his acute fear of failure.

A stately pleasure dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

This is a good example of a poem having as many dimensions as you might like to afford it. On the one hand, there is no certainty as to exactly what Coleridge is talking about. However, it is also deemed by many critics to be profoundly symbolic (art v nature etc.). The poem does appear to most to have obvious sexual imagery, though Coleridge himself did not elaborate on any hidden depths or symbolic undertones. Kubla Khan was, upon its publication, widely denigrated by contemporary critics. Today, it is viewed as a work of genius.

Interesting fact: Coleridge (possessor of an egregious opium addiction) stated that he woke one morning having had a dream/vision of the entire text of Kubla Khan. The poem remained unfinished because, as he was in the midst of writing it down, he was interrupted by a knock at the door – it was a local village tradesman. After some small talk the villager departed, but Coleridge had now lost his train of thought and could not remember the rest of the poem! Bummer!

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

Much of Wordsworth’s poetry was concerned with nature. He was a well-traveled individual, accompanied on his excursions by his sister, and lifelong companion, Dorothy. He was a prolific poet, and every school pupil will probably be familiar with his poem Daffodils.

Interesting fact: Wordsworth was born in a town with the improbable name of Cockermouth.

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes:

Thus mellow’d to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

George Gordon Byron (the 6th Lord Byron) was an egotistical and temperamental person who during his own lifetime witnessed his reputation as an individual and as a poet reach lofty heights for a time only to plummet due, in no small part, to his scandalous private life (he married a wealthy heiress who left him after a year of marriage for reasons that were greatly speculated upon but never divulged). In fact, his poetry was thereafter belittled so much he left England, never to return. His literary reputation has, of course, been more than restored since his death.

She Walks in Beauty was inspired by his being smitten at the beauty of his first-cousin, whom he met at a funeral – she being dressed in black mourning attire.

Interesting fact: Byron had a club foot, and his sensitivity to this is reflected in some of his works.

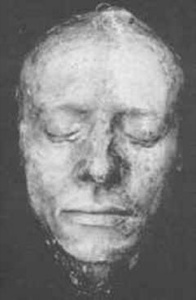

Image: Keats’ deathmask

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

’Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,-

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

Having already lost both parents, Keats wrote these soulful lines upon learning that his brother was dying and that he himself was suffering from tuberculosis. He views the nightingale’s song as lasting and eternal, and as a counterpoint to his own deeply-felt mortality. Having said this, Keats could also turn his hand to some of the most beautiful lines in the English language eg. To Autumn).

Interesting fact: Keats was a doctor who was tormented by operations carried out – as was the norm in his day – without anaesthetic.

Also, it seems that our friend Lord Byron was a little jealous of Keats’ obvious poetic talents. In letters to contemporaries he described Keats’ works as “mental masturbation”, and wrote of “Johnny Keats’ piss-a-bed poetry” Charming! To be fair, he wrote generously of Shelley (well, of his personality, if not of his works).

Now that April’s there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England – now!

Wonderful words imaginatively expressing an ex-patriate’s nostalgia for his home country

Interesting fact: Stephen King’s Dark Tower series was inspired by Browning’s famous work “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”.

Also… Browning was the first person ever whose voice was able to be heard after his death ! He attended a dinner party in 1889 (the year he died) and was persuaded to talk into a phonogram (a wax-cylinder recording device). He (somewhat falteringly) read his famous work How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix, which you can listen to here .

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with a passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints, — I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! — and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was the wife of the poet Robert Browning and, though the theme of her works was often social injustice, she shows in these well-known lines that she could turn her hand to romantic poetry – a fact well understood by her husband, who had to insist that she publish them. I think the words speak for themselves, and that it is fairly pointless to try and attribute any profound meaning to them.

Interesting fact: Barrett-Browning, having never been unwell, was prescribed opium at age 15 and suffered from unknown illnesses (so called “nervous disorders”) for the rest of her life.

Image: Fitzgerald’s grave.

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread – and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness –

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát is a (loose) translation of the work of 11th century Persian poet Omar Khayyam. It’s not a particularly consistent translation, but was a staple text for English students for many years (not so much today). It has been pointed out that the “thou” to which Fitzgerald refers in the second line of the famous tract, above, refers to a male (given that there does not appear to be any reference to women in this work).

Interesting fact: Fitzgerald was a vegetarian who, erm, apparently hated vegetables. He mostly lived off of bread and butter and fruit.

He kindly stopped for me—

The Carriage held but just Ourselves—

And Immortality.

We slowly drove—He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility—

Another who is commonly held to merit the title “genius.” This poem is reflecting, in a remarkably nonchalant manner, upon death. This particular poem has been described as “flawless to the last detail” by at least one eminent critic.

Interesting fact: reclusive in nature, only 2 of Dickinson’s 1,000+ poems were published during her lifetime – and these 2 without her permission!

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

from The Road Not Taken (1916)

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Just a few lines from two of Robert Frost’s more famous works. Frost remains one of America’s pre-eminent poets, and there is often a genial simplicity in his words that continues to make his poetry accessible. Although a common theme in Frost is individuality or independence, I cannot help but think that he doesn’t follow through enough.

Listen to Frost read The Road Not Taken.

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast.

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold.

I’m not sure what is so compelling about this; maybe it is the simplicity of a writer who liked to create imagery about everyday people in their everyday lives. Whatever the case…I do know that most people, after a few readings, come to also love this short poem without really knowing why.

Interesting fact: Williams was a doctor.

Listen to him read one of his other works (Elise)

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

…

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas, one of the 20th century’s more influential poets, wrote this to commemorate the death of his father. The poem (which in its entirety has 19 lines) has only 2 rhymes throughout.

Interesting facts: it is widely held that Robert Zimmerman adopted the name Bob Dylan as a homage to Dylan Thomas, who was somewhat of a Bohemian cult figure in the USA.

Widely believed to be an alcoholic (a rumor that Thomas himself “promoted”), there is much evidence to suggest that this was not the case (including the state of his autopsied liver).

Listen to Dylan Thomas, himself, reading the above poem.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

Who said modern poetry is dead! Undoubtedly Larkin’s best known poem, according to wikipedia “It appears in its entirety on more than a thousand web pages. It is frequently parodied. Television viewers in the United Kingdom voted it one of the Nation’s Top 100 Poems”. Cynical..yes, but also memorable.

Interesting fact: Larkin’s reputation was tarnished after his death. A biography based on his papers suggested that he was preoccupied with pornography and racism.

Contributor: kiwiboi