Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Terrifyingly Huge Rodents

The mere mention of rodents evokes dread. For millennia, they have been our unwanted guests, creeping in the shadows, feasting on garbage, and spreading disease. Why do these critters elicit such powerful emotions? Is it because they are so alien? Because rodents offer a shadowy reflection of humanity? Or is it because they’re so small, they could be hiding anywhere? That last one actually isn’t always true. Some specimens reach nightmarish proportions. Here are some of the giants.

10Nutria

The Louisiana bayou is under attack. The enemy: nutria, a 6-kilogram (14 lb) South American rat. With a voracious appetite for aquatic vegetation, these rodents turn wetlands into open water. Without the bayou to absorb storm surges, flooding could wash away southern Louisiana.

The family behind Tabasco sauce released nutria into Southern swamps in the 1930s, hoping to provide an alternative to the beaver fur trade. However, the Argentinian swamp rat pelt lacks beaver’s luster, so nutria fur never caught on. Now they are breeding out of control.

A culinary event called Nutriafest was launched to promote eating the invasive rodent. Enthusiasts tout their flesh as having more protein than beef and less fat than farmed catfish. The stats might be on the nutria’s side, but they have a public relations problem. Attempts to overcome their “wharf rat on steroids” image include re-branding them as “the bayou rabbit” or their French name, ragodin. Some suggest serving nutria to Louisiana’s prison population, but there is a fine line between experimental cuisine and cruel and unusual punishment.

9Laotian Giant Flying Squirrels

Not all enormous rodents scurry in the shadows. Some take to the air. At around 108 centimeters (42 in) long, the Laotian giant flying squirrel is not just the largest flying squirrel—it’s the largest squirrel, period. Experts observed the first known specimen in a bush meat market in Laos, and no one knows how many exist. Only 10 other specimens have been found, and they all came from freezers.

These flying squirrels don’t actually fly—they glide. A membrane of skin attached from ankle to wrist acts more like a parachute than true wings. Their tail acts as a stabilizer and cartilage rods in their wrist help steer. These arboreal adaptations weren’t enough to give the Laotian giant an edge, though—they are critically endangered.

The Laotian giant is the second known species of the Biswamoyopterus genus. The other is the Namdapha flying squirrel, which is known by a single specimen collected in 1981 from northeast India. Given the limited number of Biswamoyopterus in existence, no one knows the extent of their ranges. Other giant flying squirrels, like the red giant variety, range from Afghanistan to the islands of Southeast Asia. Like all flying squirrels, the red giant is arboreal and nocturnal.

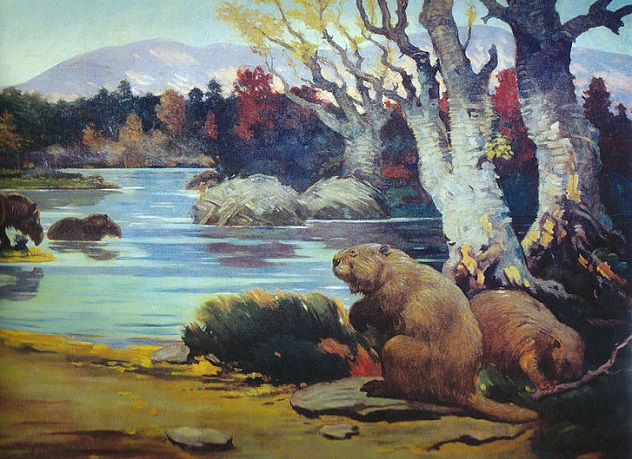

8Castoroides

Monster rodents haunted New York City long before the arrival of the sewer rat. The Big Apple had once been the home of Castoroides—bear-sized beavers who were 213 centimeters (7 ft) long and weighed over 90 kilograms (200 lb). For comparison, the largest modern beavers top out at 27 kilograms (60 lb).

These prehistoric beasts died out 10,000 years ago, along with the other Pleistocene mega-fauna of New York like mammoths and saber-tooth cats. These mega-beavers figure prominently in the mythology of several Native American tribes of the Northeast. In the legends of the Pocumtuk of Massachusetts, giant beavers are man-eaters. Given the limits of fossilized specimens, we have no idea whether they had webbed feet or a flat tail. Their teeth, however—15-centimeter (6 in) incisors—have remained for us to find. Did they use these dental daggers to chop trees? Or were these terrifying teeth designed to tear flesh?

Modern beavers are no small animal themselves. These aquatic workaholics are the second-largest rodents alive, only outweighed by the South American capybara. Seventeenth-century fashionistas’ insatiable appetite for beavers’ lustrous, waterproof fur nearly drove the European variety to extinction and served as one of the primary justifications for exploration of Canada. These remarkable creatures can chop down trees, swim underwater for 15 minutes without breathing, and turn open fields and forest into ponds with their compulsive dam-building. Only humans outmatch beavers in their ability to alter environments.

7Swedish Viking Rats

A giant brown rat recently fell victim to an industrial-sized snap trap in a Swedish suburban kitchen. The creature was over 40 centimeters (16 in) long and chewed through solid concrete to enter the home. The rat survived the snap only to suffocate when it tried to drag the trap back into its lair. While there’s no evidence that rats in general are getting bigger in developed countries, the Viking rat could be the harbinger of a coming trend: mutant monster rats.

Reports of mega rodents have emerged from all over Ireland, the UK, and the US. Experts say the brown rats are the size of cats, twice as big as they once were. Exterminators recently trapped a 61-centimeter (24 in) specimen in a Dublin flat. Not only are the rats getting bigger, they are mutating. These fast-breeding rodents have evolved an immunity to poison. Exterminators currently use bromadiolone but claim it no longer works. A 2009 study at the University of Huddersfield proved that genetic mutation has resulted in poison-resistant “super rats.” Are newer, more toxic cocktails needed? If so, how long until the rats mutate again?

6Capybara

The capybara is the largest living rodent. Haunting the steamy plains of South America, these semi-aquatic beasts top out over 45 kilograms (100 lb), about the size of labrador retrievers.

Traditionally, Venezuelans eat capybara on Easter. Their meat is a delicacy, described as “anchovy meets pork.” According to Venezuelan tradition, capybara can be eaten during Lent because the Catholic Church supposedly condoned the practice in the 18th century, claiming it is actually a type of fish. Most diners would probably prefer not to know that this monster rodent has a nasty habit of eating its own feces.

Some folks have domesticated these rodents. Pet capybara spend most of their days in pools. They get along well with cats, dogs, and horses, but reports suggest they enjoy taunting rabbits and get vexed by tortoises. A word of warning: Capybara can be aggressive. Their teeth are sharp, and bites are no laughing matter.

Far larger rodents than capybara once roamed Venezuela. In Urumaco, 400 kilometers (250 mi) west of Caracas, scientists unearthed a rodent 10 times bigger than the current heavyweight champ. Phoberomys pattersoni was a relative of modern guinea pigs. Eight million years ago, this 700-kilogram (1,500 lb) “Guineazilla” roamed the banks of ancient rivers, possibly in huge packs. Urumaco was a home to giants of all varieties—the largest turtle ever, some of the largest crocodiles, and an array of unidentified monstrous fish once lived alongside Guineazilla. Experts believe these oversize rodents went extinct because they were too large to hide from predators. Bigger isn’t always better.

5The Gough Island House Mouse

Killer rodents have taken over Gough Island. Two million mice run rampant on this lonely outpost in the South Atlantic. These bloodthirsty rodents are 50 percent larger than mice elsewhere. The non-native critters fuel their supersized growth with Atlantic petrel chicks. Gough Islands is a principal breeding ground for the sea bird—but it won’t be for long.

On nearby Tristan da Cunha, black rats have already devoured a separate petrel population. These invasive rodents have no predators to fear on these far-flung islands. The Gough Island mice have been known to attack and devour chicks of the Tristan albatross, which are 300 times larger than the mice. Analysis reveals that 1.25 million of the 1.6 million petrel chicks born per year on Gough Island are gobbled up by mice.

Remote South Atlantic outposts aren’t the only islands affected by invasive rodents. The Farallon Islands, 45 kilometers (28 mi) from San Francisco’s Golden Gate, have developed a nasty reputation for infestations. As a refuge manager at the US Fish and Wildlife service explained, “There are so many mice it looks like the ground is moving . . . When you stay on the island, they crawl over you when you sleep in your bed.”

Brought over accidentally by fur traders, the Farallon mice boast the highest population density of non-native island rodents anywhere in the world. Everyone agrees that something needs to be done to combat the mice and stop their predation of the endangered ashy storm petrel, but not everyone agrees on the method. The plan to carpet bomb the island with pesticide from helicopters has been met with disapproval. Many are concerned with the ethics of poison and the impact it will have on both petrels and burrowing owls, which prey on the island’s mice. Plus, the poison would need to kill every mouse. A single pregnant female could repopulate the island.

There is a precedent for island rodent eradication. Recently, Rat Island in the Aleutian chain re-branded itself “Hawadax Island” after biologists successfully exterminated the invasive brown rat population on the island with poison. Not surprisingly, there are fewer bleeding hearts in Alaska than the Bay Area.

4Josephoartigasia

In 1981, scientists excavating around Montevideo, Uruguay found the remains of a 53-centimeter (21 in) skull. It was larger than a cow’s, but it bore an unmistakable pair of incisors. The bones belonged to the Josephoartigasia, the largest rodent ever. This prehistoric beast dominated the woodlands of South America four million years ago.

Analysis of the skull suggested a creature as large as a bull, up to 244 centimeters (8 ft) long and weighing over a ton. This monster resembled a giant capybara and was more closely related to guinea pigs and porcupines than mice and rats. The teeth of the Josephoartigasia suggest a diet of aquatic vegetation and fruit, but that does not imply passivity. These mega-rodents lived in a hostile world of saber-tooth cats, meat-eating marsupials, and 3-meter (10 ft) birds of terror. Perhaps their teeth were used for defense or by males to fight over breeding rights.

3Bosavi Woolly Rats

In 2009, scientists stumbled upon a lost world: the Bosavi crater. Even the local Kasua tribe, who provided trackers for the research party, rarely set foot inside the crater. With steep walls nearly 800 meters (0.5 mi) high, the Bosavi crater is an evolutionary island. This volcanic depression in the Papua New Guinea highlands contained 40 species new to science and believed to exist nowhere else on Earth: 16 amphibians, one gecko, three fish, a gang of spiders and arachnids, a marsupial, and the largest known true rat. The rat has been tentatively named the “Bosavi woolly rat,” as it is so new to science that it has no official name. The 81-centimeter (32 in) creature with a lush, silvery coat was incredibly docile, indicating that it has had no exposure to humans.

While the Bosavi woolly rat is the largest living rat, much larger specimens stalked the jungles of Southeast Asia as recently as 1,000 years ago. Archeologists in East Timor unearthed the bones of a rat three times larger than the Bosavi specimen dating from this period. These extinct giants weighed up to 6 kilograms (13 lb).

East Indonesia is a “hot-spot” for rodent evolution. The giant rat expedition uncovered the remains of 13 rodent species, 11 of which were unknown to science. Given the dense forest and difficult terrain of East Timor, it is possible that new, even larger specimens are waiting to be discovered. No one knows what is out there.

2Giant Hutia

Over 100,000 years ago, the Caribbean island of Anguilla was ruled by monsters: rats twice the size of men. These bear-sized beasts are known as Ambyrhiza, also called the giant hutia, and they were 1,000 times larger than a modern rat. These creatures were heavy and slow, indicating that they had no predators. The fossil record confirms that there were no other large mammals on the island at this time.

The island the giant hutia stalked was much larger than it is today. Due to reduced sea levels during the last ice age, St. Barts, St. Martin, and Anguilla were all part of one island known as Greater Anguilla, which was 12 times larger than the current island. When the ice age ended and the sea level rose, the giant hutia could not adapt to its smaller environment. It went the way of the dodo.

There are much smaller hutia cousins still alive in the Caribbean, though most top out at just over 2 kilograms (5 lb), a far cry from the giants of Anguilla. Modern hutias are all too common around Guantanamo Bay, where they are known as “banana rats.” The “banana” part of their name refers not to their taste in food but the size and shape of their feces.

1Cape Porcupines

The Cape porcupine of southern Africa is the largest of its prickly brethren. These beasts can grow up to 27 kilograms (60 lb), making them the third-largest living rodents. Only the capybara and beaver outweigh these monsters.

Cape porcupines have over 30,000 individual quills. These 8-centimeter (3 in), razor-sharp hairs detach easily and regrow, providing the most terrifying line of defense in the rodent family. Porcupine quills have been used in decorations and tools for millennia, and new applications are emerging all the time. For example, experiments revealed that porcupine quills pierced pig flesh with half the pressure required for a hypodermic needle. Additionally, their barb-like design makes them extremely difficult to remove, which could prove beneficial for securing medical implants.

Given their truly terrifying weaponry, it’s fortunate that Cape porcupines are not aggressive. They spend their time on the ground, foraging for roots, tubers, and other delicacies from the forest floor at night. These mellow monsters are among the longest-lived in the rodent family, holding on for 20 years in captivity. Cape porcupines mate for life, meaning their marriages often last longer than the human variety.

Abraham Rinquist is the Executive Director of the Winooski, Vermont branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is co-author of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.