Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Fascinating Cultures That May Soon Disappear

Tribal people throughout the world are defending themselves against the incursion of a modern society that scorns their rights and their unique ways of living. Here are 10 fascinating indigenous cultures that are on the verge of extinction.

10The Korowai

The primitive Korowai have a long tradition of cannibalism, but it’s their tree houses in southeastern Papua, Indonesia that make them fascinating. A family of up to eight people will live in a wooden house with a sago-leaf ceiling that’s built 6–12 meters (20–40 ft) above the ground on a single tree. Sometimes, a house rests on several trees with wooden poles adding support.

The Korowai live in the trees to avoid imagined attacks after dark by walking corpses and male witches on the ground. Each house physically lasts about a year. But they’re so critical to each person’s identity that time is defined by the houses that a person has lived in. For example, a unit of time may be described by the number of houses that fell apart during it. An event such as a birth, death, marriage, or killing happened at the time of a specific house. An era consists of a series of events that occurred when a series of houses were inhabited.

The Korowai usually die before middle age because they lack any kind of medicine. There are about 3,000 tribe members left. Wearing only banana leaves, these hunter-gatherers eat bananas, sago, deer, and wild boar.

Until the 1970s, when anthropologists came to study them, most Korowai didn’t know that outsiders existed. But in recent decades, the younger Korowai have drifted away to settlements built by Dutch missionaries. Soon, only old tribe members will remain in the trees. Their culture is expected to disappear within the next generation.

9The Samburu

For hundreds of years, the Samburu roamed semi-arid northern Kenya in search of water and grass for the livestock that are their sole source of food. The Samburu are now threatened by intense droughts, and they face an ever greater threat from the Kenyan authorities. The police rape the Samburu, beat them, and burn their houses down.

The recent harassment began after two American wildlife charities bought Samburu land and gave it to Kenya to create a national park. The charities believed that they were purchasing land from a private owner, possibly former Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi. Thousands of Samburu families were forced to relocate or live like squatters on the edge of their disputed land. The Samburu are now challenging their violent eviction in court.

But life for young Samburu girls is brutal within their tribe, too. A systematic rape ritual called “beading” is supposed to prevent promiscuity in girls, some as young as six years old. A close male acquaintance, often a relative, who wants an early promise of marriage will contact the child’s parents and put a necklace of red beads on the girl. “Effectively, he has booked her,” says Josephine Kulea, a Samburu woman. “It’s like a [temporary] engagement, and he can then have sex with her. ”

The girls are forbidden from getting pregnant, but no contraceptives are used, so many become pregnant despite the taboo. The infants who don’t die naturally are killed or given away. If a girl keeps her baby, she won’t be permitted to marry when she’s an adult.

Kulea has tried to rescue some of these girls by placing them in a shelter and moving their babies to orphanages.

8The Loba

Hidden in the harsh terrain of the Nepalese Himalayas is the former Tibetan kingdom of Mustang, also known as Lo. To enter its capital, Lo Manthang, is to step back in time to a 14th-century walled city steeped in a purely Tibetan Buddhist culture.

Mustang was closed to most foreigners until 1992 and was only accessible by foot or on horseback until recently. We’re now learning about its history from ancient texts, painted murals, and other religious artifacts discovered in Mustang caves built into steep cliffs.

The people of Mustang, called the Loba, live off the land with almost no modern technology and few educational opportunities for their children. But the Loba do have a history of cultural resistance against Chinese rule. When the Dalai Lama sought refuge in India in the 1960s, CIA-backed resistance fighters (called the Khampas) made Mustang their base. Eventually, the CIA stopped its support, and Nepal was pressured by China into taking military action against the Khampas. The Dalai Lama called on the Khampas to surrender. The few who didn’t committed suicide, and the resistance was formally over. China has closely watched this region ever since.

Now, China is funding a new highway between the cities of Lhasa in Tibet and Kathmandu in Nepal that will make Mustang part of a major trade route. While some of Mustang’s people welcome modernization, their leaders are concerned that their Tibetan Buddhist culture will be lost forever, especially as more residents leave the area for better jobs and education elsewhere.

7The San

We’ve previously looked at the San’s religious beliefs, their language and even their giraffe dance. Now, we’re going to examine the possible extinction of Africa’s first people.

The government of Botswana evicted these hunter-gatherers from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) in the name of conservation while permitting diamond mining, fracking, and tourism. The San (or Bushmen) were forcibly resettled into camps with goats or cattle to become herders, a lifestyle they don’t understand. Unemployment is rampant.

As Goiotseone Lobelo described it, “The police came, destroyed our homes and dumped us in the back of trucks with our belongings and brought us here. We are getting AIDS and other diseases we didn’t know about; young people are drinking alcohol; young girls are having babies. Everything is wrong here.”

The San fought the government in court and won the right to return to CKGR. But government officials only granted this to the few whose names were in the court documents. The government has also banned all hunting except on ranches or game farms, which effectively destroys the San way of life.

According to Jamunda Kakelebone, another displaced San, “Our death rate is increasing. They want to develop us. To eradicate us. Our people die of HIV and TB. When we were on our own, our death rate was low. Old people died of age. Now, we go to funerals. It’s terrifying. In 20 years, it’s going to be bye-bye, Bushmen.”

6The Awa

Before their territory was invaded, the nomadic Awa tribe had lived in harmony with the Amazon rain forest in Brazil for centuries. They were hunter-gatherers who made pets of orphaned animals. They shared mangoes with parakeets and their hammocks with coatis, which are similar to raccoons. The women sometimes breastfed monkeys and even small pigs.

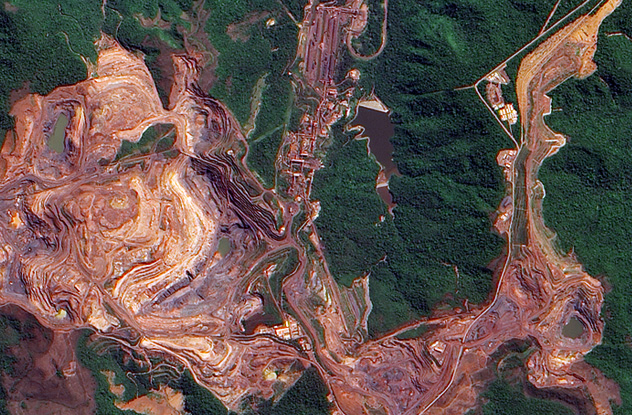

Then, in 1967, American geologists on a survey mission accidentally landed their plane on the world’s largest iron ore deposit, which was in the Carajas Mountains. That led to the Great Carajas Project, a huge mining operation backed by the World Bank and industrialized nations such as the US and Japan. The Awa’s territory was invaded by loggers, ranchers, and settlers, who destroyed large swaths of the rain forest for the minerals and other resources there.

The invaders also killed many of the Awa, sometimes by shooting them and other times by giving them gifts of poisoned flour. There are only about 350 Awa left, 100 of whom have no contact with outsiders.

Finally, under pressure from rights groups such as Survival International, the Brazilian government launched Operation Awa to evict the invaders and return the dwindling Awa to their land. The question is whether Brazil will make sure the loggers and ranchers don’t return.

5The Cocopah

The Cocopah (which means “River People”) are fighting to preserve their dying culture against governments that manipulate the tribe’s access to water. These natives farmed and fished for over 500 years in the delta of the lower Colorado River, which lies in Arizona in the US and the states of Baja California and Sonora in Mexico. At one time, this people numbered around 22,000, but now they’ve dwindled to about 1,300. Only 10 native speakers remain. Traditionally, there was no written language.

Starting in 1922, the US and Mexico diverted most of the Colorado River away from the delta where the Cocopah lived. Two million acres of wetlands dried up, crippling the tribe’s ability to farm and fish. Then, during the 1980s, the US managed El Nino flooding by opening dam reservoirs, sending floodwaters surging through the delta and destroying the Cocopah’s homes. The tribe was forced to move to El Mayor, which had no water rights or arable land.

A couple of years ago, the US and Mexico agreed to let about 1 percent of the Colorado River flow to the delta in an effort to restore the wetlands. But even if that works, the Cocopah face another problem.

In 1993, the Mexican government created the Alto Golfo de California y Delta del Rio Colorado Biosphere Reserve, a conservation project that soon restricted the Cocopah’s fishing so much that they couldn’t make a living. Many members of the tribe left to find jobs elsewhere. As 44-year-old Monica Gonzalez says, “Sometimes I think our leaders talk about the Cocopah as if we had already died, but we are alive and still putting up a struggle.”

4The Mursi

A tribe of less than 10,000 people from southwestern Ethiopia, the Mursi are known for the lip-plates worn by their women. Lip-plates are a symbol of social adulthood and potential fertility. At 15 or 16 years old, a girl has her lower lip pierced, inserting a wooden plug to hold the cut open until it heals. Over the next several months, the girl will stretch her lip with a series of increasingly larger plugs. The most persistent girls will eventually wear lip-plates of at least 12 centimeters (5 in) in diameter.

Although the Mursi are considered nomads by the Ethiopian government, they’re actually quite settled. Depending on the rainfall, they may move to find a place with water to grow crops like sorghum, beans, and maize. They also need grasslands to feed their cattle—which are not only a food source, but also a currency to trade for grain and to validate social relationships like marriage.

In recent decades, the Ethiopian government has begun large-scale development of the Mursi’s land into national parks and commercial irrigation schemes. Thousands of the tribe have been evicted. Aid agencies agree that abuses such as beatings and rapes have occurred, but not in a “systematic” way. It’s possible that some international aid to Ethiopia, though intended for local road construction and other services, is being used by the government to forcibly resettle the Mursi. This will likely destroy their traditional culture.

3The Tsaatan

The Tsaatan’s affection for and dependence on their reindeer makes them unique. The reindeer give them milk and cheese as well as transportation across the frigid mountains and taiga (a swampy forest) of their homeland in northern Mongolia.

There are only about 500 Tsaatan left. Disease and problems from inbreeding have caused their reindeer to dwindle, too. So the Tsaatan no longer wear reindeer hides or use animal skins to cover their tepees. They’re nomads, moving every five weeks to find lichen for their beloved animals.

The tribe has an uneasy relationship with tourists. Too many visitors come without an interpreter, litter the environment, and take photos as if the Tsaatan are in a zoo. It’s also important to them that tourists ride horses that won’t hurt the reindeer.

But the Tsaatan’s biggest problem is that their 3,000-year-old culture may not survive past this generation. Without the government assistance that they once relied on, the Tsaatan are struggling. The children turn to computers and other technology to prepare them to live in the modern world. Younger people are leaving the taiga for the cities, and the older Tsaatan are afraid they’ll be left alone.

2The Ladakhis

Imagine the most idyllic culture you can. Patience, tolerance, and honesty are held above all other values. People always help one another, and there’s no money but also no poverty. Lying, stealing, aggression, and arguments are almost unknown. Major crimes simply don’t exist. Everybody is irrepressibly happy. You’re imagining the actual Ladakh culture that existed for centuries before the modern world intruded to destroy it like the serpent in the Garden of Eden.

Of course, life wasn’t really perfect. Set high in the Himalayas in the northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh is a barren desert in the summer and a frozen moonscape in the winter. With few resources and no modern technology, the Ladakhis established farms, supplemented by herding. Ladakh was almost completely isolated until a road was built in 1962 to connect this area with the rest of India. But modernization didn’t have a major impact on this society until 1975, when tourism slithered in.

Then, like Adam and Eve after eating the fruit, the Ladakhis saw their nakedness (or, in this case, their primitive lifestyle) and became ashamed. They compared themselves to the free-spending tourists and the glamorous people they saw in films and on TV. For the first time, they felt poor and inferior. Their self-sustaining culture and their family structure began to break down as they chased happiness through material wealth.

As they modernize, they’re becoming selfish, competitive, frustrated, and argumentative. They’re becoming intolerant of other religions, dependent on the government, insecure, and alone in a crowded world. They’re becoming us.

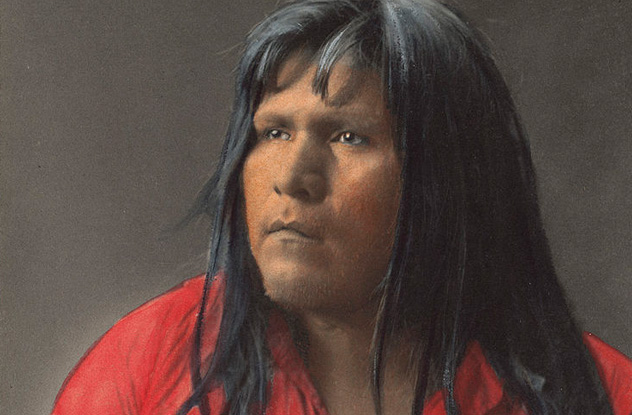

1The Huaorani

The Huaorani have a long history of using deadly spears and blowguns against everyone else in their Amazon rain forest home in Ecuador. For them, revenge is a lifestyle.

Energy companies want to drill in the Amazon rain forest to extract the huge reserves of crude oil that lie beneath the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) area of Yasuni National Park. Despite environmental concerns, it’s coming down to a battle between the Ecuadorian government and the Huaorani. Both sides have alternated between high-minded words and possible ransom demands whenever it suits their purposes.

In 2007, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa proposed that governments around the world give Ecuador $3.6 billion in exchange for Ecuador not drilling the ITT. In 2013, when it became clear that world leaders weren’t paying up, Correa went to Plan B, drilling for oil. He also abandoned his commitment to protect Amazon tribes from drillers by denying that the tribes exist. Correa claims to need the Amazon oil revenue to help the poor.

As for the Huaorani, some claim that they’ll fight to the death with blowguns, machetes, and spears if oil companies drill on their land and threaten their way of life. But the Huaorani are no military match for the government.

Weya Cahuiya, who represents a Huaorani tribal organization, says, “Every time the oil companies expand, they divide us. There are fights between families because some people get things and others don’t. The government needs to pay us. All of us. They need to respect us and if they want to come in, they have to pay us or we’ll kill them.”