Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Ominous Italian Mysteries That Are Still Unexplained

Italy is globally renowned for its breathtaking art, historical importance, and delicious cuisine. Unfortunately, it’s also notorious for its turbulent history, government corruption, and organized crime, which have combined to give the country some pretty intriguing mysteries.

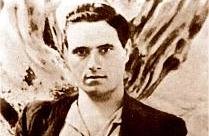

10The Assassination Of Salvatore Giuliano

In the 1940s, the bandit Salvatore Giuliano styled himself as a Sicilian Robin Hood, stealing from rich landlords and redistributing the spoils to the peasants. He was also a Sicilian nationalist, longing to end Italian rule and give the island its independence. He even wrote President Harry Truman, suggesting that Sicily be made an American state. But by the time World War II was over, Giuliano had shifted his support from the peasants to the Mafia and landowners, who could provide the funds he needed for his guerrilla army. He fought communists and the government alike until his death in 1950, when he was shot by the police while resisting arrest.

Or was he? An investigation by the journalist Tommaso Besozzi eventually revealed that the official version of Giuliano’s death was false, as the bandit’s cousin and trusted friend Gaspare Pisciotta confessed to betraying Giuliano in exchange for a pardon from the authorities. In this version of events, it was not the police who shot Giuliano, but Pisciotta himself. Curiously, Pisciotta also ended up perishing in mysterious circumstances, dying four years later in a Palermo prison after drinking a poisoned cup of coffee.

Inspired by these strange events, many conspiracy theorists insist that Giuliano faked his own death and fled to the United States. The body in Giuliano’s grave, they contend, is much too short. Moreover, Giuliano’s mother and sister both fainted when they heard of his death, so his family never actually identified the body. After a decade-long investigation, Giuliano’s supposed remains were exhumed in 2012 and DNA tests found a 90 percent chance that the body was his. Still, others are certain that Giuliano still lives, which would make him an impressive 92 years old.

9The Caronia Fires

Caronia is a small town on the northwest coast of Sicily, situated between a railroad and the sea. In the early months of 2004, the town’s Canneto area was the site of a string of inexplicable fires and bizarre electrical activity. There were reports of mattresses, chairs, televisions, kitchen appliances, unconnected electrical wires, and a variety of other objects suddenly bursting into flames for no apparent reason. Cars locked themselves and mobile phones rang without being called. The incidents briefly stopped when the town’s power supply was shut off, but they began again several weeks later and have struck periodically since then.

While the local population has attributed the source to everything from the devil to poltergeists to UFOs, government officials, scientists, and representatives from the railway and telephone companies have all been unable to provide a conclusive answer. Some experts have suggested electrical charges released by underground volcanic shifts are to blame, but the head of the Sicilian Civil Protection Agency felt no clear cause could be found: “The cause of the fires seems to have been static electric charges. What we don’t understand is why there were these static electric charges.”

8The Disappearance Of Mauro De Mauro

During the 1960s, Mauro De Mauro was one of the biggest investigative journalists in Italy. He worked for the communist paper L’Ora, which notably covered links between the Mafia and corrupt politicians. In 1970, De Mauro was hired to do research for the Francesco Rosi movie The Mattei Case, which dramatized the life of Enrico Mattei, an influential businessman and politician who died in a mysterious plane crash in 1962. In September, he told colleagues that he had uncovered “a scoop that is going to shake Italy.” But he never got a chance to reveal it. On September 16, 1970, he was seen getting out of his car to talk with some men in front of his house. De Mauro then climbed into their car, and the party drove away. He was never seen again.

It was well-known that De Mauro had a dark past. During World War II, he was a strong supporter of Mussolini’s fascist government. He even joined the Decima Flottiglia MAS, a notoriously violent unit of the Italian Royal Navy that mostly operated on land and fought members of the Italian Resistance. Because of his old fascist connections, De Mauro might have stumbled onto plans for the Golpe Borghese, a coup plotted by the Mafia and various Italian fascists, which was ultimately never carried out. Over the years, informants like Tommaso Buscetta have alleged that De Mauro was murdered by the Mafia for knowing too much.

7The Ustica Massacre

On June 27, 1980, Itavia Airlines Flight 870 departed from Bologna to Palermo, carrying 81 people. Almost an hour into the flight, the plane vanished from radar screens. A few hours later, plane debris was noticed in the Tyrrhenian Sea, near the island of Ustica. The crash left no survivors.

It is still unclear why Flight 870 crashed. One popular theory asserts that terrorists had planted a bomb onboard, an idea supported by Senator Giovanni Pellegrino of the Parliamentary Commission on Terrorism. Another theory is that the DC-9 might have been hit by a military missile intended for a Libyan plane.

The missile theory became more and more prominent during the 1990s, with the Italian government and its NATO allies being accused of accidentally shooting the plane down. Radar records released to the public in 1997 showed seven warplanes in the area during Flight 870’s disappearance. It was also discovered that the debris of a Libyan fighter jet was found three weeks after the crash near the southern region of Calabria. Flight 870, it has been suggested, might very well have been hit by a missile intended for that plane.

6The Bruno Facchini UFO Case

Bruno Facchini was an honest and hardworking factory worker in Varese, a northwestern city near Milan. On April 24, 1950, Facchini working a late shift when he stepped outside to make sure none of the factory’s circuit breakers had been damaged in a thunderstorm. Near the factory doors, he saw a brightly glowing light and went to investigate. As he approached the light, he realized it was coming from a hovering circular object, with a sort of ladder hanging from a rectangular opening. He then saw two small figures wearing what looked like masks and diving suits on the ground. Terrified, he immediately turned and ran.

As he fled, Facchini reported being struck by a beam of light, which threw him to the ground. Facchini then watched the figures climb the ladder into the craft, which flew away. He filed a police report the next day, which resulted in investigators finding burn marks on the ground, along with a green metallic substance analysis later found to contain copper and tin. About a week later, Facchini claimed that his back had turned black, then yellow, before gradually returning to normal. He also experienced pain in his neck, where the beam of light had hit him. In a 1981 interview, Facchini said the encounter had given him a psychological trauma he was never able to recover from. Even after such a long time had passed, he still suffered fevers and a feeling of hot flashes on his face. In hindsight, he suggested that the figures resembled the astronauts who later walked on the moon.

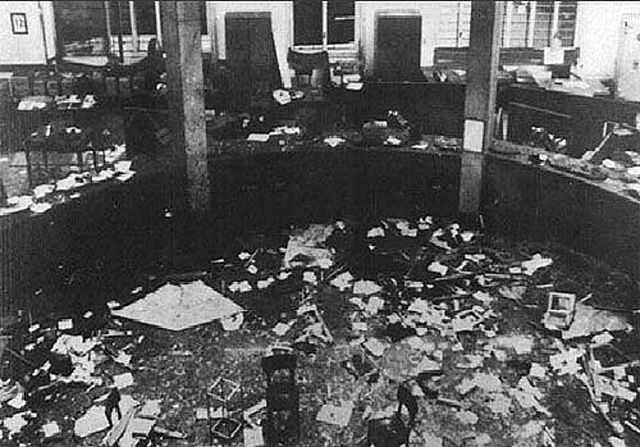

5The Perpetrators Of The Fontana Bombing

On December 12, 1969, a bomb exploded in Milan’s Piazza Fontana, killing 16 people and wounding 58 others. The same day saw two further bombs detonate in Rome, while another went off near a Milanese opera house, but there were no other deaths. The attacks were initially blamed on anarchists. One of the suspects, a railway worker named Giuseppe Pinelli, apparently jumped to his death from the police station where he was being held. Pinelli’s bizarre defenestration was officially labeled a suicide, but leftists insisted he was murdered by one of the policemen guarding him, Luigi Calabresi. Three years later, Calabresi was shot on his way to work. His murderer was never caught.

The far right and far left each accused the other of planting the bombs, sparking a series of terrorist attacks by extremist groups on both sides. Most notably, the neo-fascist group Ordine Nuovo launched a terror campaign called “The Strategy of Tension,” which was allegedly intended to intimidate the public into accepting an overthrow of the Italian government. For the next five years, Ordine Nuovo seem to have bombed train stations and pinned the blame on communist groups like the Red Brigades. Eventually, suspicion fell on them, and three of their members were arrested in 1972. The accused were acquitted in 1985. Another trial in 1999 led to the accusations of three other members, but they were also acquitted in 2004.

4The Monster Of Florence

“Il Mostro di Firenze” (“The Monster of Florence”) was responsible for a series of unsolved double homicides between 1968 and 1985. His victims were always couples, usually caught while parked in their cars. They were all shot at close range with the same weapon, a .22-caliber Beretta. The female victims always had their genitals elaborately mutilated, suggesting the killer might have been a skilled surgeon or butcher. Despite one of the longest and most expensive investigations in Italian history, the Monster of Florence has never been caught.

The killer first came to public attention in June 1981, when 30-year-old Giovanni Foggi was found dead in his car. His 21-year-old girlfriend Carmela Di Nuccio was discovered lying nude a short distance away. The couple had been shot and then stabbed, apparently with a type of knife specifically used by scuba divers. Di Nuccio’s genitalia had also been carefully removed. Reporting on the case, La Nazione noted its similarity to a double homicide that had taken place seven years earlier, also in the Florentine countryside. The next killing occurred a few months later, throwing Florence into panic and bringing national media attention.

A fourth killing happened about eight months later, accompanied by a letter to the Florence police containing a newspaper cutting about the 1968 double murder of a man and woman caught having sex in their car. However, that case had already been solved. The murderer was the woman’s husband, Stefano Mele, a Sardinian immigrant who confessed to the crime the next morning. A La Nazione reporter who interviewed Mele discovered that he had killed his wife with several other Sardinian men, and the police came to believe one of these men was the Monster of Florence.

A Sardinian named Franceso Vinci was arrested, but was released after a gay German couple were found dead in their Volkswagen (the killer is thought to have mistaken one of them for a woman). Ten months passed before the Monster killed again, this time cutting off the female victim’s left breast. The government offered a hefty bounty for help in catching the Monster and a special team was assembled to investigate.

The final killing happened in the summer of 1985, with the killer again removing the female victim’s left breast. A few days later, a female prosecutor in the case received an envelope containing the victim’s nipple. The Monster was never heard from again.

In 1994, a Tuscan farmer named Pietro Pacciani was arrested for the murders. Pacciani was a reasonable candidate—he was a violent alcoholic who had once killed a traveling salesman in a jealous rage after catching him with his wife. He had also served a prison sentence for raping his daughters. However, Pacciani insisted he was innocent and was eventually acquitted. Since then, theorists have been split between blaming the Sardinians, Pacciani, or even Satanists.

3The Lucedio Abbey

The Lucedio Abbey, located in the province of Piedmont, is said to be one of the most haunted places in Italy. It was built by Cisternian monks in 1123 on land given to them by the Marquis of Monferrato. It later became a major cultivator of rice in the region, until it was secularized and sold off by the Vatican in 1784. After passing through a number of different owners (including Napoleon) the abbey has now been incorporated into a modern rice farm.

Due to its (alleged) grisly history, the abbey has spawned a number of legends. When the area is foggy, ghostly monks can be discerned wandering through the mist. One of the buildings possesses a pillar that inexplicably becomes wet, “crying” for all the evil things it has seen. During a restoration of one of the abbey’s houses, a perfectly preserved man is said to have been found buried inside a wall. More corpses can supposedly be found in the crypt, where the mummified bodies of former abbots sit in a circle of thrones, preventing the release of a monster trapped underground. The surrounding countryside is also said to be haunted: A hooded figure can be seen roaming the countryside, and one local church possesses a painting of an organ pipe and piece of sheet music known as the “Sheet of the Devil.” If the notes on the painting are played in reverse, the piece can apparently summon Satan himself.

2The Murder Of Wilma Montesi

In April 1953, the body of 21-year-old Wilma Montesi was found on a beach in Ostia, a town near Rome. She was half-naked, dressed only in her blouse and panties. Prior to the discovery of her body, nobody had seen her in two days, after she left dinner with her family to board a train to Ostia. The police quickly ruled out suicide and any foul play. Montesi was, after all, an ordinary working-class girl, engaged to a policeman and very much looking forward to the wedding. What could she possibly get mixed up in? Instead, the police concluded that Montesi went to dip her feet in the water, was swept in by an sudden wave, and drowned. After five days, the case was closed. It was nothing but a tragic accident.

But the Montesi Affair, as it came to be known, wasn’t quite that simple. In fact, it soon shook the entire political establishment, leading to the resignation of the foreign minister and a loss of faith in the democratic government of post-Fascist Italy. It all started a few months after Montesi’s death, when a neo-Facist newspaper called Attualita claimed that Montesi’s death was not an accident. Instead of the good girl the media portrayed her as, she was involved with a narcotics ring and a participant in wild orgies at the nearby estate of Capocatto, owned by an elderly nobleman named Marquess Ugo Montagna. After an opium overdose, Montesi passed out. She was then dumped on the beach, where she was left to die.

The paper’s editor, Silvano Muto, soon found himself in court, charged with “spreading false and tendentious news to disturb public order.” Challenged to support his claims, Muto brought in the Milanese aristocrat Anna Maria Caglio, one of Montagna’s former mistresses. Caglio alleged that Montagna and his musician friend, Piero Picconi, the son of the foreign minster, ran a drug ring and were behind the disappearances of a number of other young women. The local authorities had been bribed to keep things quiet and close the case.

Caglio’s tesimony caused an uproar. Public opinion was polarized, and both the elder Picconi and the Roman chief of police, Saverio Polito, resigned from their posts. Montagna, Piero Picconi, and Saverio Polito were later tried for their alleged crimes, but all three were acquitted. Montesi’s father, a respectable carpenter, while at first skeptical of his daughter’s activities, soon came to believe that she was murdered. Some 62 years later, the events that led to Montesi’s death are still not clear.

1The Death Of Pier Paolo Pasolini

Outside of Italy, Pier Paolo Pasolini is best known for his extremely controversial 1975 film Salo, still infamous to this day for its scenes of sexual violence and (simulated) coprophagia. Aside from his role as an iconoclastic filmmaker, Pasolini was also a gifted poet and public intellectual, somehow finding time to be gay, Marxist, and a Catholic.

In the early morning of November 2, 1975, several weeks before Salo‘s Paris premier, Pasolini’s badly mutilated corpse was found on a beach in Ostia (the city’s beaches seem to be a popular spot for shocking unsolved murders). A few hours previously, police had arrested a 17-year-old male prostitute named Pelo Pelosi for speeding in an Alfa Romeo, accusing him of stealing the car after he tried to run away. The car was later identified as belonging to Pasolini, and Pelosi quickly confessed to murdering him.

According to Pelosi, Pasolini had picked him up that night at a train station, taking him to a restaurant and then the beach. When Pelosi refused his request to sodomize him with a wooden stick, Pasolini snapped and struck him. Overpowered by an older man who was far stronger than him, Pelosi panicked and grabbed the stick, beating Pasolini to death with it. He then fled to the car and sped away, hitting what he thought was a bump. He was initially convicted along with “unknown others,” but the authorities came to agree that he had acted alone.

Pasolini’s family and friends, however, were not convinced. The forensic examiner insisted that “Pasolini was the victim of an attack carried out by more than one person.” Additionally, Pelosi’s confession contradicted several details of the crime scene. A green sweater that belonged to neither man was found in the backseat of the car and a bloodstain was found on the roof of the passenger’s side. Some motorcycles and another car were also reportedly following Pelosi before he was stopped by the police.

In 2005, Pelosi changed his story, claiming to be an innocent in a television interview. The real murderers, he insisted, were three neo-fascists who shouted that Pasolini was a “queer” and a “dirty communist” as they killed him. Pasolini’s murder being politically tinged is not entirely far-fetched—he had repeatedly criticized the right-wing Italian government of the day.

However, Pasolini’s friend, Sergio Citti, launched an investigation of his own, which concluded that Pasolini was killed while negotiating with a gang of thieves who had stolen spools of film from Salo. The writer Fulvio Abbate argued he was murdered by the notorious Magliana gang. And then there is his cousin and fellow gay poet, Nico Naldini, who accepts the official version of what happened. Pasolini, he wrote, was a victim of his own “fetishistic rituals” and “attraction to boys who made him lose his sense of danger.”

Tristan Shaw is an American college student obsessed with mysteries, literature, and cannoli.