Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Fateful Telegrams That Changed The Course Of History

One of the most fateful telegrams in history was perhaps the very first, sent by Samuel F.B. Morse in 1844. Referencing the Book of Numbers, it said, “WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT?” This extremely important communications method helped to bridge distances in a way never before seen and shaped the course of modern history.

10 Goering Telegram

Hermann Goering was one of Hitler’s most trusted advisers, and in June 1941, the fuhrer issued a secret decree stating that if he were incapacitated, kidnapped, or killed, Goering would assume control. But as the war dragged on, Hitler became increasingly suspicious of Goering, egged on by Goering’s enemy Martin Bormann. While Hitler was surrounded by advisers in his bunker with Soviet troops closing in, Goering was holed up in the town of Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, 800 kilometers (500 mi) south.

At 12:56 AM on April 23, 1945, Goering sent a secret telegram to Hitler:

My Fuhrer:

General Koller today gave me a briefing on the basis of communications given to him by Colonel General Jodl and General Christian, according to which you had referred certain decisions to me and emphasized that I, in case negotiations would become necessary, would be in an easier position than you in Berlin. These views were so surprising and serious to me that I felt obligated to assume, in case by 2200 o’clock no answer is forthcoming, that you have lost your freedom of action. I shall then view the conditions of your decree as fulfilled and take action for the well being of Nation and Fatherland. You know what I feel for you in these most difficult hours of my life and I cannot express this in words. God protect you and allow you despite everything to come here as soon as possible.

Your faithful Hermann Goering

According to Albert Speer’s autobiography, Martin Bormann seized on this and a follow-up message as evidence that Goering was a traitor planning a coup. Hitler was listless at first but flew into a rage with increased prodding, stripping Goering of his titles, expelling him from the Nazi party, and calling him lazy and corrupt. After this, according to Speer’s account, the fuhrer sank into a bitter depression. A week later, he and Eva Braun killed themselves, and many believe that the Goering telegram was a major factor in that decision.

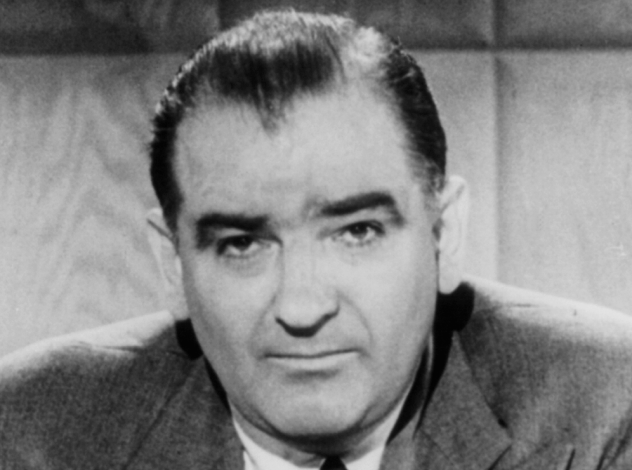

9 McCarthy’s Telegram To Truman

On February 9, 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy gave a speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, in which he accused 200 US State Department employees of being members of the Communist Party. Two days later, he sent a telegram to President Truman, mentioning his revelation at Wheeling that, “The State Department harbors a nest of communists and communist sympathizers,” and claiming to have the names of 57 of them. McCarthy reminded Truman that he had himself created a board to investigate the State Department and found hundreds of “fellow travelers . . . dangerous to the security of the nation,” of which supposedly only 80 were expelled, possibly due to the influence of suspected Communist spy Alger Hiss.

He would go on to demand that Truman order Secretary of State Acheson to hand over the original list of names and give Congress a full accounting of the infiltration. Failure to do so would “label the Democratic Party of being the bed-fellow of international communism.” Truman wrote (but probably never sent) a nasty reply accusing the McCarthy of insolence, dishonesty, and irresponsibility, saying it was the first time he’d ever heard of a senator trying to discredit his government before the world.

McCarthy handed out copies of his telegram to the president to reporters, helping to spark a media firestorm over his claims, featuring headlines like “Purge State Department Reds, Senator Urges” and “Get Acheson’s List of Commies on Staff, Senator Bids Truman.” An article about the telegram in the Gazette explained that the reason the FBI couldn’t act against communists in the State Department was due to the fact that they couldn’t legally do so without the approval of the Justice Department, which would not act without State Department approval. The firestorm of speculation over McCarthy’s telegram helped usher in a new era of Red paranoia.

8 Zimmerman Telegram

While World War I raged in Europe, US president Woodrow Wilson had been elected to a second term in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” The United States had already severed diplomatic relations with Germany over their decision to begin unrestricted submarine warfare, but there was still a general reluctance to get involved in a European quagmire. One of the factors that helped to reduce that reluctance was the Zimmerman telegram.

In January 1917, British cryptographers decoded an encrypted telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German minister to Mexico, von Eckhardt. The telegram informed the ambassador that while Germany hoped the United States would remain neutral, Germany extended a proposal for alliance with Mexico, on the basis of making war and peace together, with Germany providing generous financial aid and an understanding that Mexico was to reclaim the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The exact details were left up to von Eckhardt, and Zimmerman also requested that the Mexican president help mediate between Germany and Japan.

On February 24, 1917, the British authorities gave a copy of the telegram to the US Ambassador to the UK, who promptly sent it to President Wilson. Shocked, Wilson proposed to Congress to start arming ships against possible German attacks and authorized the State Department to release the telegram to the media on March 1. The public was outraged, though many saw it as a forgery. Then, for some bizarre reason, Zimmerman himself announced that it was real. The combination of the telegram and German attacks on US shipping helped to harden the resolve of the American population against Germany, allowing Congress to declare war against the Second Reich.

7 Deptel 243

On August 24, 1963, Henry Cabot Lodge, US ambassador to South Vietnam, received a hastily written telegram which revealed a sudden shift in US policy toward Ngo Dinh Diem, the South Vietnamese president. The US had supported him for 10 years, and Lyndon Johnson once referred to him as the “Churchill of Asia.”

Though possessing impeccable anti-Communist credentials, Diem’s nationalism and independent streak had ruffled American feathers, but it was his brother-in-law and right hand man Ngo Dinh Nhu who really annoyed them. Nhu had ordered a crackdown on Buddhist monk protesters, which led to a distressing number of self-immolations, which Nhu’s wife Tran Le Xuan mockingly referred to as “barbecues.” It was also rumored that Nhu was planning to make peace with the North Vietnamese and possibly stage a coup against Diem.

The telegram stated in no unclear terms:

US Government cannot tolerate situation in which power lies in Nhu’s hands. Diem must be given chance to rid himself of Nhu and his coterie and replace them with best military and political personalities available. If, in spite of all of your efforts, Diem remains obdurate and refuses, then we must face the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved.

By November, the military had staged a coup with Washington’s backing and assassinated Diem and Nhu. Hopes of a renewed military effort against the North unraveled, and a period of chaotic and inept rule caused political unrest and military setbacks, eventually forcing the US to intervene directly in the Vietnamese conflict. Some consider the diplomatic telegram to have set off a course of events that led to the inevitable destruction of South Vietnam.

6 Indian Mutiny Telegram

The 1857 revolt by Indian soldiers could easily have taken the British completely by surprise if it wasn’t for the telegraph system. The first telegraph line on the subcontinent had been laid by the East India Company in 1850 between Kolkata and Diamond Harbour, one of many technical innovations that the locals viewed with suspicion but which ultimately served as investments to secure imperial power.

On May 11, 1857, telegraph master Charles Todd went out to check on the telegraph lines when he was murdered by mutineers sent to take out the lines of communication. However, his two assistants, William Brendish and J.W. Pilkington, remained at their posts waiting for word from the military while providing updates on the mutiny breaking out in Delhi to the telegraph station at Ambala.

Eventually, Brendish and Pilkington were forced to flee, sending one final dispatch:

We must leave office. All the bungalows are on fire, burning down by the sepoys of Meerut. They came in this morning. Mr. C. Todd is dead, we think. He went out this morning and has not yet returned. We learn that nine Europeans were killed. We are off. Goodbye.

General George Anson, commander-in-chief in India, was at a dinner party in Simla, 106 kilometers (66 mi) from Ambala, on May 12 when he finally received the message. The word from Delhi would spur Anson into action, giving him time to mobilize troops to crush the rebellion. H.C. Fanshawe would write begrudgingly of the event in 1902: “Irresponsible chatter of one clerk with another that warned Punjab of what happened at Delhi, and enabled the authorities there to take steps which at least scotched further mutiny and saved the position for the time being.”

5 George Kennan’s Long Telegram

In 1946, the American charge d’affaires in Moscow George Kennan sent a long, detailed, 8,000-word telegram to the State Department outlining his opinions on the Soviet Union and US policy toward the communist power. In it, he described the basic outlook of the Soviet Union in the postwar era and its background, the outlook on practical policy on both official and unofficial levels, and practical deductions to be drawn to formulate US policy.

Marxist-Leninist doctrine as well as the culturally based “instinctive Russian sense of insecurity” meant that the Soviet Union could not foresee long-term peaceful coexistence with the capitalist world. According to Kennan, the Soviets saw themselves as encircled by antagonistic capitalist powers and beset by reactionary and bourgeois elements as well as by capitalism’s very nature, which was prone to internal struggles and wars. The implications for Soviet policy were to strengthen their own power, while exploiting divisions within and between capitalist societies, by supporting Communist elements and undermining socialist and social democratic “false friends.”

There was a spirited reaction to the telegram in Washington, which highlighted the Soviet threat to countries like Turkey and Iran and argued that the only logic the Soviets understood was the “logic of force.” Kennan’s opinion that Soviet expansionism could only be curtailed by strong resistance struck a chord with a Truman administration which was increasingly inclined to deal with the Soviets with military and economic pressure rather than diplomacy. This helped to lay the foundation for the American containment policy toward the Soviet Union. For his efforts, Kennan was named the ambassador to the Soviet Union.

4 ‘Work On The Mouse Fast’

The first major character for Disney Studios was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a mischievous character with a personality and appearance very similar to a certain famous mouse, though with obviously different ears. He was created by animator Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney, who had heard from Disney’s film distributor Charles Mintz that Universal Studios was looking for something with a rabbit. The character appeared in 26 silent animated shorts from 1927–28. After the first short, “Trolley Troubles,” Oswald delighted audiences with his antics until Disney went to Mintz hoping for an increase in pay due to the increasing costs of producing the shorts.

Instead, Mintz wanted to cut Disney’s pay by 20 percent, and Disney learned that Mintz controlled the rights to the character. Disney decided to relinquish control of Oswald, sending his brother Roy a fateful telegram:

Roy, I just lost the rights to Oswald. Tell Ub to get to work on the mouse fast or we are screwed!

Disney made some sketches of the new character himself on the way back to Los Angeles from New York by train and initially sought to name the character Mortimer after a childhood pet. His wife intervened, and the character of Mickey Mouse was born, animated by Ub Iwerks but with the personality and voice of Walt Disney. In the end, Mickey proved more popular than Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a character that eventually ended up absorbed into Disney intellectual property in 2006.

3 Willy-Nicky Telegrams

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia were third cousins and frequently corresponded with each other using the common language of English, referring to each other affectionately as “Willy” and “Nicky.” The kaiser and tsar were close, often taking vacations and hunting together and even dressing each other up in the other’s respective military uniforms (pictured above). Neither of the cousins wanted war, but they were divided by differing interests and the inexorable pull of power and politics.

During July 1914, Willy and Nicky exchanged a series of telegrams trying to find a diplomatic solution to the growing conflict. Nicolas hoped to avoid a war entirely, while Wilhelm was concerned with keeping Russia neutral, believing that a conflict in Europe was inevitable.

At 1:00 AM July 29, the tsar wrote:

Am glad you are back. In this serious moment, I appeal to you to help me. An ignoble war has been declared to a weak country. The indignation in Russia shared fully by me is enormous. I foresee that very soon I shall be overwhelmed by the pressure forced upon me and be forced to take extreme measures which will lead to war. To try and avoid such a calamity as a European war I beg you in the name of our old friendship to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.

Nicky

This telegram crossed with one sent by the Kaiser at 1:45 AM:

It is with the gravest concern that I hear of the impression which the action of Austria against Serbia is creating in your country. The unscrupulous agitation that has been going on in Serbia for years has resulted in the outrageous crime, to which Archduke Francis Ferdinand fell a victim . . . all the persons morally responsible for the dastardly murder should receive their deserved punishment . . . On the other hand, I fully understand how difficult it is for you and your Government to face the drift of your public opinion. Therefore, with regard to the hearty and tender friendship which binds us both from long ago with firm ties, I am exerting my utmost influence to induce the Austrians to deal straightly to arrive to a satisfactory understanding with you. I confidently hope that you will help me in my efforts to smooth over difficulties that may still arise.

Your very sincere and devoted friend and cousin

Willy

In spite of several days of trying to find a solution, the logic of the European network of interlocking alliances and military mobilization timetables meant that there was little way for the two leaders to avoid their countries going to war, regardless of the love and affection they may have felt for each other. Still, their correspondence was perhaps the diplomatic effort that came closest to halting the march of Europe toward years of bloodshed and brutality.

2 Kruger Telegram

Kaiser Wilhelm II seems to have abominable luck with telegrams. On January 3, 1896, the Kaiser approved the dispatch of a telegram to Paulus Ohm Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, a state unrecognized by Great Britain. Wilhelm congratulated the president on the successful repulsion of a group of British irregulars sent from the Cape Colony to Transvaal under the command of Leander Starr Jameson with the hopes of inciting an anti-government uprising against the Transvaal Republic by mostly British miners. It ended in fiasco with 65 British dead and one Boer commando killed.

The Kaiser’s message read:

I express my sincere congratulations that you and your people, without appealing to friendly powers for help, by dint of your own vigor, have been able to restore the peace against the armed hordes that invaded your country as disturbers of the peace, and to preserve the independence of the country against outside attacks.

Wilhelm I.R.

This telegram proved to be a miscalculation. The Jameson raid had been immensely popular with the British public, who were incensed by German gloating and perceived interference. The British were irritated at the very notion that Kruger could have appealed and received help from “friendly powers,” and that the kaiser was treating the Transvaal Republic as a legitimate state.

The result of all this was that the botched Jameson Raid became a point of patriotic pride rather than national embarrassment and stirred up anti-German sentiment among the British people. Queen Victoria wrote:

As your Grandmother to whom you have always shown so much affection, I must express my regret at the telegram you sent President Kruger. It is considered very unfriendly towards this country . . . The action of Dr Jameson was of course very wrong . . . but . . . I think it would have been far better to have said nothing.

In the end, the fallout over the Kruger telegram helped Britain to avoid political fallout from the failed raid, galvanized the public’s support for further action against the Transvaal, and likely hastened the arrival of the 1899 Boer War.

1 The Last Telegrams

New technologies eclipsed the telegram in the late 20th century, and telegram couriers were phased out in the late 1960s and early 1970s. By the 21st century, most preferred more convenient communication methods like e-mail and SMS. In 2006, Western Union ended its famous telegraph service after 155 years of operation, having gone from a peak of 200 million telegrams in 1929 to a mere 20,000 messages in 2005. Western Union reported that the last 10 telegrams sent in the US included birthday wishes, condolences on the death of a loved one, notification of an emergency, and a couple of people deliberately trying to send the last American telegram ever.

Another era came to a close in 2013 when the Indian Telegraph Service, a state-owned BSNL communications company, was shut down 163 years after the technology was first introduced to the country. The system, known as Taar, once a network of telegraph offices spread across the country dealing with millions of telegrams every year, was the last of its kind in the world, though only 75 telegraph offices remained. The last days of operation were unusually busy as people thronged to send telegrams to friends and families as keepsakes.

The last telegram sent in India was sent to Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi, called Pappu (“the simpleton”) by many social media users. Some claimed Gandhi family cronyism to have been behind it. Netizens responded with posts like, “Out of 1.2 billion people, Pappu gets the last telegram. Holy crap,” and, “(Narendra) Modi sold tea when he was six. Sonia (Gandhi) waited tables when she was a teenager. The real problem is Rahul Gandhi. He can do neither even after 40. But meanwhile he is busy saying ‘hello hello’ to the last telegram he received and assures us that bad news will continue to flow even if telegram is discontinued.”

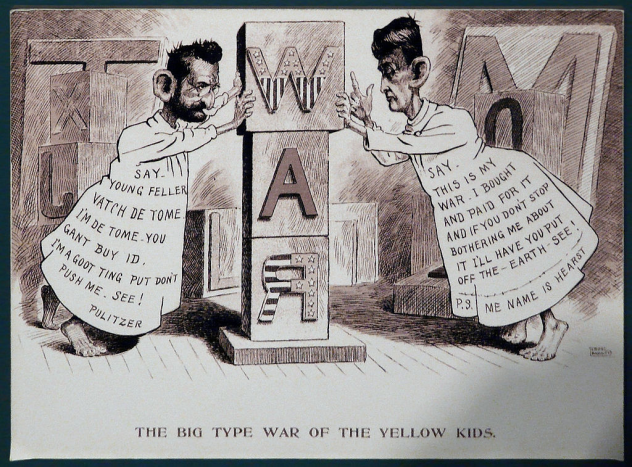

+ Remington-Hearst Telegrams

These telegrams would have had more impact if there was any real evidence that they were ever sent, but there is more reason to believe them apocryphal. Telegraphy legend describes an exchange between distinguished artist Frederic S. Remington, who was stationed in Cuba in January 1897, and William Randolph Hearst, the notorious newspaper magnate. Remington supposedly sent this message to Hearst in New York:

Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return.

Hearst allegedly replied tersely:

Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.

The exchange is meant to represent Hearst’s arrogance and the role that his media empire played in drumming up American public support for war against Spain. The original source of the memoir is James Creelman, who gave the anecdotal evidence of the telegrams as proof of the sinister power of yellow journalism to mold and manipulate public opinion.

Hearst denied sending any such telegram, and there are a number of factual problems with the anecdote. In January 1897, Creelman was far off in Europe, and the timeline doesn’t match up. The US didn’t declare war on Spain until February 1898, while in January 1897, Hearst’s New York Journal was still confidently predicting that the Cuban rebels would defeat the Spanish and achieve independence. Furthermore, the contents of the telegrams would have been uncharacteristic of both Hearst and Remington, and even if they were sent, they would have been extremely unlikely to pass by the draconian Spanish censors.

David Tormsen is still available for singing telegram services. Email him at [email protected].