Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Overwrought Media Scare Campaigns About The Internet

Moral panics over new social developments and technologies date back to the time that people grumbled over how reading and writing stunted memory and how imported Minoan artwork was turning good Egyptian youths into deviants. In an era where old media is barely clinging to life, it’s not surprising to see a few media-driven moral panics about the Internet and social media.

10 Game Of 72

A 13-year-old girl named Emma from France who disappeared for three days told police she had been playing the “Game of 72” (or “12, 24, 72”), a social media challenge in which participants try to disappear and stay out of contact with friends and family for either 12, 24, or 72 hours. The story was published in the English-language French newspaper The Local and soon spread to the hysterical British tabloid media and the United States.

Meanwhile, terrified parents posted about the supposed game in social media, warning each other to be vigilant lest their children suddenly disappear. One French group opposed to dangerous games for children advised parents to warn their children that it would be better to fail the game than risk something tragic happening.

However, it soon emerged that the game was most probably imaginary, made up as an excuse by the girl to cover her disappearance with a boyfriend for three days. While some pointed to the fact that secrecy was supposedly part of the game, authorities could not find any evidence of the game actually taking place. Most posts and tweets about the game merely linked to news reports.

When police responded to media questions about the game in Vancouver, a newspaper article was written as if there had been an official police warning. It was included next to a quote from a supposed online awareness expert saying, “The game’s popularity shows that parents need to stay up to the minute on their kids’ computer habits.” But Vancouver police had issued no such warning. Other than a single tweet from a small Massachusetts police station, neither had anyone else.

9 Miss Lebanon’s Selfie

In early 2015, Miss Israel, Doron Matalon, posted a selfie to Instagram featuring her, Miss Japan, Miss Slovenia, and Miss Lebanon, Saly Greige. The Lebanese media and the Internet immediately erupted in fury as technically Israel and Lebanon were in a state of war. Lebanese television station Al Jadeed noted that one of Greige’s hobbies is reading, so she should have known enough about the political situation to avoid being in such a position. Lebanese newspaper The Daily Star ran the headline “Miss Lebanon’s selfie with Miss Israel sparks uproar.”

With some calling for her to be stripped of her title, Miss Lebanon took to Facebook to defend herself, saying that she was preparing to take a picture with Miss Japan and Miss Slovenia when she was photobombed by Miss Israel. “Since the first day of my arrival to participate to Miss Universe, I was very cautious to avoid being in any photo or communication with Miss Israel,” Greige wrote in English on her Facebook page. “I was having a photo with Miss Japan, Miss Slovenia and myself, suddenly Miss Israel jumped in, took a selfie, and put it on her social media.”

Miss Israel also responded on Facebook to the outcry: “It doesn’t surprise me, but it still makes me sad. Too bad you cannot put the hostility out of the game, only for three weeks of an experience of a lifetime that we can meet girls from around the world and also from the neighboring country.”

Some Lebanese wondered why the Miss Universe contestant was getting so much heat when Lebanese Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil had been so recently photographed with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a rally against terrorism in Paris.

8 Time Magazine’s Usenet Scare

Long ago in the hoary age before Facebook, YouTube, or any kind of real social networking service, there was Usenet. Even in those days, there were media scares about frightening, new technology. In July 1995, Time published an article entitled “On Screen Near You: Cyberporn.” The cover image showed a young child staring wide-eyed and scared at a screen, while images inside showed a man having sex with a computer and a lollipop on a computer monitor in front of a small child with a suspicious person lurking behind the computer.

Time said that Internet porn was “popular, pervasive and surprisingly perverse.” While that is true enough today, it wasn’t the case in 1995. Time‘s methodology in researching the article was fatally flawed and soon discredited.

Time claimed that a research team at Carnegie Mellon University had surveyed Usenet and the wider Internet and discovered “an awful lot of porn online,” with “917,410 sexually explicit pictures, descriptions, short stories, and film clips” uncovered in the course of the survey. They also claimed that 83.5 percent of the images in Usenet groups were sexually explicit and that they could be accessed by any man, woman, or child with an Internet connection.

The problem was that the “research team” was actually just a single undergraduate student, Martin Rimm. He had actually compiled most of his research from private adult bulletin board services, most of which were not accessible through the Internet and sold pornography to adults with credit cards. The claim about images on Usenet was also a misinterpretation because Rimm had only said that 83.5 percent of images on specifically pornographic Usenet groups were sexually explicit.

Internet activists quickly tore apart the data and methodology, with one comparing the article’s methods with surveying adult bookstores at Times Square and applying the findings to merchandise at Barnes and Noble. Time backpedaled, and the study was quickly repudiated, perhaps one of the first victories of the Internet over old media.

7 Predators Of Myspace

Back when people still used Myspace, it was considered a dangerous haven for online predators to exploit young people who had placed their personal information online for all to see. NBC’s Dateline called the site “a cyber secret teenagers keep from tech-challenged parents . . . It’s a world where the kids next door can play any role they want. They may not realize everyone with Internet access, including sexual predators, may see the pictures and personal information they post.”

The panic led to the raising of a bit of dodgy legislation to force schools and libraries to restrict minors from accessing commercial social networking websites and chat rooms, a category so broad that it could theoretically apply to almost any website. The effect of the legislation was so costly that it would disproportionately impact poorer school districts. Much of the impetus for this moral panic came from Dateline’s program “To Catch a Predator,” which helped to create much of the mythos of the online predator.

However, Myspace actually made a solid effort to root out sexual predators on their site. Between 2007 and 2009, Myspace identified and blocked 90,000 registered sex offenders from using the site. In 2009, a task force led by the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University released a 278-page report which concluded that the danger to children from sexual predators on social media networks was minimal.

Chief Executive John Cardillo of Sentinel Tech Holding said, “This shows that social networks are not these horribly bad neighborhoods on the Internet. Social networks are very much like real-world communities that are comprised mostly of good people who are there for the right reasons.”

6 Social Media And Suicide

In July 2015, The New York Times reported on the contemplated suicide of Kathryn DeWitt, a gold-medal decathlete and straight A student who had engaged in self-harm and considered committing suicide over perceived failures. According to the article, DeWitt’s feelings of failure and hopelessness were exacerbated by exposure to idealized representations of the social lives and successes of her classmates and peers on social media networks like Facebook and Instagram. Some psychologists believe that the “perfect” images posted on social media give the impression that everyone except you is doing great, when the reality is that everyone has problems.

But the idea that social media is causing suicide is not entirely backed up by statistics. The suicide trend for school-age children stayed relatively constant from 1993 to 2012, with suicides declining slightly from 1.18 to 1.09 per 1 million children. According to the CDC, suicide rates for persons aged 10–24 years decreased between 1994 and 2012 for males and fluctuated for females, ending up slightly higher in 2012 than in 1994. The CDC doesn’t blame this on social media but instead on the increasing popularity of suffocation as a means to commit suicide, which has a higher lethality rate than other methods.

A report by the American Journal of Public Health paints a more nuanced picture. Social media can facilitate suicide in some cases. Pro-suicide websites and chat rooms distribute information about suicide preparation and methods. Victims of cyberbullying and online harassment are twice as likely to attempt suicide as those who are not victims. In Japan and South Korea, suicide pacts organized through the Internet have become a scourge. Basically, the spread of information through social media and the Internet in general provides suicide information to people who might not otherwise have it.

However, social media can also reduce the number of suicides by providing easy access to prevention programs, crisis help lines, and other support and educational resources that help to fight against suicide. YouTube features many public service videos related to suicide prevention, while Facebook has installed a number of features designed to combat cyberbullying and provide suicide risk alerts.

5 Snapchat Sexting

Snapchat’s ability to send photo messages with a self-destruct feature proved popular with young people but was a nightmare for parents. They believed that their children would soon be sexting each other without the parents ever finding out. They were also worried that images sent through Snapchat could be saved by taking a screen capture or recovering them with special software. One nightmare scenario was having one’s child send a naked photo to a girlfriend or boyfriend and then watching it spread throughout social media. Another nightmare scenario was having the technology used as a medium of child pornography.

While many of these concerns are valid, they are often exaggerated. Only around 1 percent of teenagers have ever sent a sext, a much lower rate than the number of teenagers who’ve pilfered their parents’ liquor cabinet or had a smoke behind the woodshed. Earlier studies claiming that 20 percent of teenagers had sexted were severely skewed by including young people in their early twenties, who are much more likely to engage in the behavior.

New technology has almost always been used to facilitate sex, from selling nude photos taken at early photography studios to the early success of VHS porn. Much of the moral histrionics from the older generation comes from that all-too-familiar juxtaposition of young people, sex, and unfamiliar and bewildering new technology. As Dan Savage put it: “It’s a generational paranoia, because young people are doing something that old people didn’t—because they couldn’t—and can’t now, because no one wants to see them naked.”

Indeed, Snapchat was originally designed to prevent long-term consequences of posting photos, such as having your embarrassing photos seen by a future employer. When a recipient takes a screen capture of a Snapchat photo, the application alerts the sender. In general, this serves as a deterrent against posting photos sent through Snapchat without permission. There is usually enough social stigmatization of such behavior to make violations rare and seen as extremely rude.

4 Paracetamol Challenge

The painkiller paracetamol, usually known as Tylenol or acetaminophen in North America, has been linked in the UK to a teen suicide craze driven by social media. A moral panic erupted after a schoolboy from Ayrshire in Scotland was supposedly taken to the hospital after overdosing on the drug, leading the Coatbridge police to tweet: “We’ve heard about the #paracetamolchallenge. DONT get involved in this. It causes liver & kidney failure . . . and death.”

The warning was later picked up by The Scotsman, which wrote about a supposed social media craze of children using Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to encourage each other to take excessive amounts of paracetamol. The British tabloid the Daily Mirror also published two articles on the subject, and soon, the hashtag #paracetamolchallenge was dominated by people posting warnings against taking part in the dangerous challenge.

However, the challenge wasn’t real. The Guardian reported that Alan Ward, head of schools at East Ayrshire council, had been contacted by police and told ITV News: “We have been communicating with parents, encouraging them to monitor their child’s safety on social media. We are urging parents to talk to their children about the potential dangers of taking paracetamol, and to discourage their children from engaging in any online activity in support of this dangerous craze.”

But there was no actual evidence of the challenge on the Internet and no evidence that any teenager had taken part in it. A few weeks later, the Coatbridge police took a somewhat sensible route when they followed up with this tweet: “Hoax or not our advice remains the same . . . DONT DO IT.”

3 Collarbone Challenge

Emerging from the Chinese social media site Weibo, the collarbone challenge was meant to show off how skinny you were by trying to balance as many coins on your collarbone as possible. Soon, thousands of young women across China were uploading photos of themselves laden with as many coins as possible. One of the more popular images was of actress Lv Jiarong, who managed an impressive 80 coins. From China, the trend soon spread to Japan, Southeast Asia, and India.

The collarbone challenge came soon after the belly button challenge, the object of which was to reach around your waist and touch your belly button. There has been somewhat of a negative reaction to these challenges on the Western Internet. The trend is seen as yet another example of body shaming through social media.

Believing the trend to be harmful, body image blogger Leyah Shanks told the HuffPost UK Lifestyle in an interview:

It’s accentuating the idea that thinner is better and subsequently pushing down every other body type. Being able to do this is not what we should be basing our beauty and self worth on. I’m not sure why these odd trends keep appearing. I wish that the power of social media would be used to spread body love instead of encouraging dangerous comparisons.

If you view the pictures, it soon becomes clear that many of the participants are just doing it for fun. People were soon trying more and more ridiculous items for the challenge, including strawberries, coffee cups, cell phones, pasta, liquor bottles, chocolate, live turtles, and durians. This shows that the Chinese Internet community is usually capable of lampooning its own silly social media trends without the Western media tut-tutting.

Besides, the challenge doesn’t make sense as a celebration of thinness. According to Dr. Lu, chief of the orthopedics department at Chongqing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, success at the challenge depends on how one’s individual collarbones are structured, not on one’s fitness level.

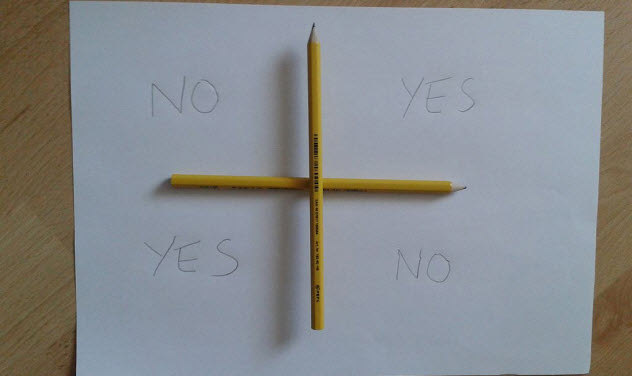

2 Charlie Charlie Challenge

Based on a traditional Spanish children’s game called Juego de la Lapicera, the “Charlie Charlie” challenge appeared on the English-speaking Internet as a supposed way to contact either a Mexican demon or the ghost of a child who had died of child abuse.

The game is played by drawing a cross on a piece of paper, labeling two quadrants as “yes” and the other two as “no.” Then you put two pencils crossing each other on the paper as dividing lines for the quadrants. First, you ask: “Charlie, Charlie, are you there?” Then you ask a yes or no question, like “Does Suzy Jenkins like me?” The ghost or demon named “Charlie” supposedly moves the pencil, making a prediction.

The game was given some spooky creepypasta history, with a reference on a website of spooky stories from 2008 saying that failing to properly bid farewell to Charlie after the game caused a group of friends to be harassed by a terrifying, dark figure. In 2015, the game mysteriously started trending again on social media, possibly due to a hysterical local news broadcast in the Dominican province of Hato Mayor that warned of a “Satanic” game being played by young people.

The incorrigible Daily Mail soon picked up on the trend, reporting that parents in Hato Mayor were convinced that their children were possessed by Satan due to the game. According to the UK tabloid, deputy headmistress Jovita Jimenez of the Juan Pablo Duarte Primary School said: “The students and parents alike have been terrified. Many have appeared with inexplicable bruises on their bodies.” A local doctor was also quoted by the tabloid as saying: “It’s a craze that has gone too far . . . It’s very dangerous for a young child to play with contacting the paranormal and diabolical.”

The truth of the Charlie Charlie phenomenon is more prosaic than paranormal. Balancing one pencil atop another creates an unstable system. A slight breeze or whispered question can easily cause one of the pencils to move, appearing to indicate an answer to a question. The power of suggestion also plays an important role, just as in similar games such as Ouija boards.

1 Happy Slapping And The Knockout Game

Back in 2005, there were concerns in the UK over a supposed trend called “happy slapping,” which involved youths attacking an innocent person while accomplices filmed it with a mobile phone to share or upload to the Internet. The trend was real. One uploaded video called “Bitch Slap” showed young men attacking a woman at a bus stop. Another entitled “Bank Job” showed criminals attacking an ATM customer. On a London community web forum, a user named “Happyslapper2” described the trend this way: “If you feel bored wen ur about an u got a video phone den bitch slap sum norman, innit.”

While there were media concerns about the trend, there simply weren’t enough videos online to describe happy slapping as an epidemic. Besides, such videos were the perfect evidence for prosecution, so concerns about happy slapping were short-lived.

In 2013, a similar phenomenon called the “knockout game” emerged in the United States. Reports from Brooklyn described groups of teens playing a vicious anti-Semitic game called “knock out the Jew.” Rabbi Yaacov Behrman, executive director of the Jewish Future Alliance, reported that many of the victims were children. “Kids talk, especially on social media,” Behrman said in an interview with CNN. “There’s a buzz about this.”

Some reports stated that gangs of youths were competing in an expanded version of the game, often called “knockout,” the object of which was to knock out an unsuspecting victim with a single punch while filming the episode with a cell phone. The results were then uploaded to YouTube.

There is no doubt that random violence and horrific incidents like these took place. But the narrative of a violent trend driven by social media was exaggerated. Alan Noble wrote on Patheos:

Nobody seems to have any evidence that it’s spreading, or that it’s new, or that it’s racially motivated, or that black youths are the ones typically responsible, or that whites are typically targeted. This hasn’t stopped Mark Steyn, Thomas Sowell, and Matt Walsh from describing this specifically as a crime committed by blacks against whites, CNN from claiming that it is “spreading,” or Alec Torres at NRO from say it is “evidently increasing [in] popularity.” Most sources claim that it is spreading, and a number of sources claim that it is racially motivated. But how do they know? Where are they getting their data from?

David Tormsen is sad he hasn’t caused an online moral panic yet. Email him at [email protected].