Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 People Who Shaped Our View Of History

When it comes to our view of the past, be it an entire era or one man’s lifetime, the details often come mainly from one source. Even today, we see attempts at rewriting history (such as Turkey’s repeated denials of the Armenian genocide), and that’s with all of the technological advances we have at our disposal. Though fragments are usually all we have left, a few men have stood out through history, shaping our opinions and beliefs about the outcomes of wars and millennia of cultural history.

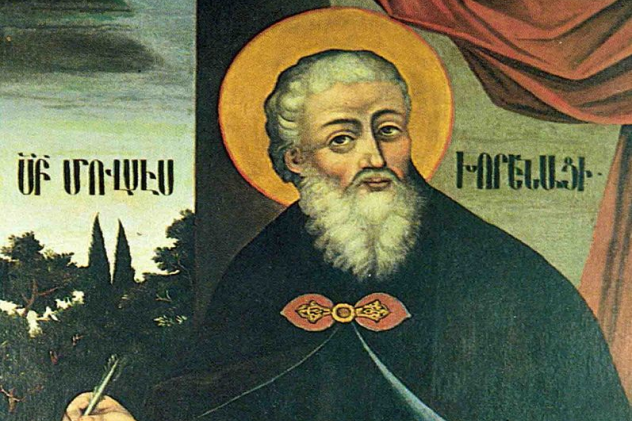

10 Movses Khorenatsi

All Of Armenian History (Up To That Point)

Movses Khorenatsi (sometimes Anglicized as Moses of Khoren) was born shortly after the start of the fifth century AD and is one of the largest and most important figures in Armenian historiography. His life’s work, Patmut’yun Hayots (The History of Armenia), was written thanks to the insistence of a prince in the Bagratuni dynasty. It was the first attempt to look at the country’s history before it converted to Christianity about two centuries prior.

In addition, he was the first to document the oral history of Hayk, the legendary patriarch of Armenia, and Bel, a Titanid of Babylon who followed him when he immigrated to Armenia’s current location near Mount Ararat. Hayk and Bel, as well as their massive armies, fought a violent battle, which ended in Bel’s death. (The Greeks have a similar story, with Zeus taking Hayk’s place.)

Khorenatsi also claimed to have gone to Babylon for his research, determined to use their ancient records to uncover the date on which his country was founded. Initially seen as simply another myth by many scholars, recent genetic work has found that his stated date, 2492 BC, is possibly quite accurate.

9 Manetho

3,000 Years Of Egyptian History

Though details of Manetho’s life are scarce (as is often the case), approximations place his life sometime in the third century BC. He was an Egyptian priest as well as a prominent historian. He was so prominent, or at least well-respected, that the Macedonian king of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, is said to have been the one who commissioned his life’s work, Aegyptiaca (The History of Egypt).

Unfortunately, none of Manetho’s original writing still exists. The only surviving pieces come from later historians or translations, some over 1,000 years after the fact. On top of that, his work was later used in polemics written by various Egyptian, Jewish, and Greek authors, each of whom had a different opinion on which was the oldest (and therefore the best) civilization. (The references were often heavily edited in order to conform to the author’s viewpoint.)

To Egyptologists, the most important part of his work, one which has survived mostly intact, is his king list, his most commonly cited list and the one that ordered Egyptian history into dynasties. However, the surviving citations often differ on the years, order, and names of various pharaohs, another unfortunate side effect of not having Manetho’s original text.

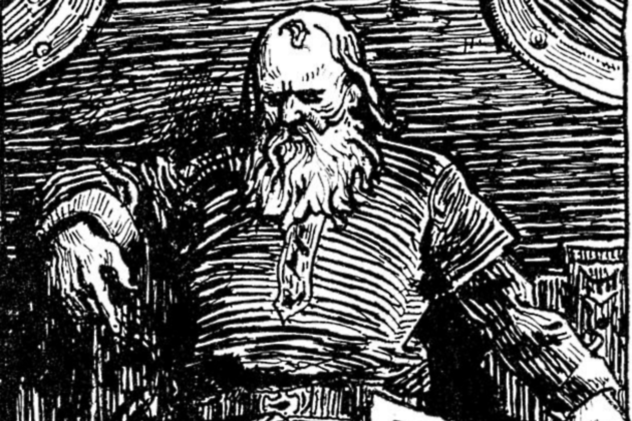

8 Snorri Sturluson

Northern European History And Mythology

One of the most important figures in the historiography of Iceland as well as one of the first to organize and document their national myths by compiling oral traditions, Snorri Sturluson was born at the tail end of the 12th century. In addition to being a prolific writer and historian, he was an accomplished politician, twice holding the office of law speaker at the Althing, an extremely respected position. However, politics would be his downfall, as Sturluson didn’t want to bring Iceland under Norwegian rule. When Norway eventually took control, he was branded a traitor (for his role in attempting to overthrow the king), and he was later killed by one of his sons-in-law.

As far as his literary and historical life go, the Prose Edda is perhaps his best-known work, forming the basis of our knowledge of Norse mythology. Almost entirely consisting of poetry, the Prose Edda is also one of the earliest examples of euhemerism in Northern Europe. Euhemerism derives its name from the Greek mythographer Euhemerus, who was one of the first to suggest that much of mythology could be rationalized as natural events which had undergone a supernatural transformation as their stories spread throughout the centuries.

Heimskringla is Sturluson’s other major work, and it contains sagas of all the Norse kings, from their mythological and prehistoric origins to his own time. However, its use as a historical document is up for debate.

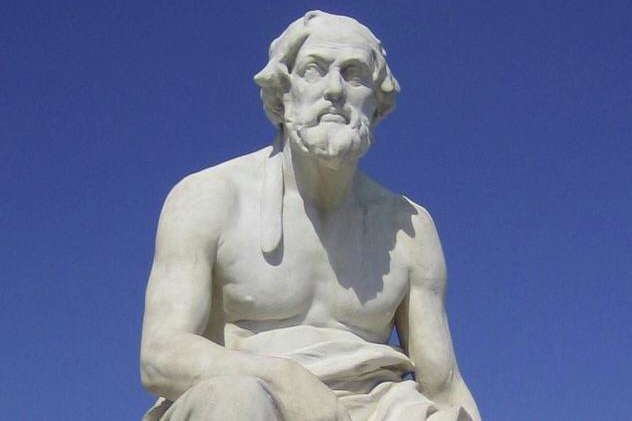

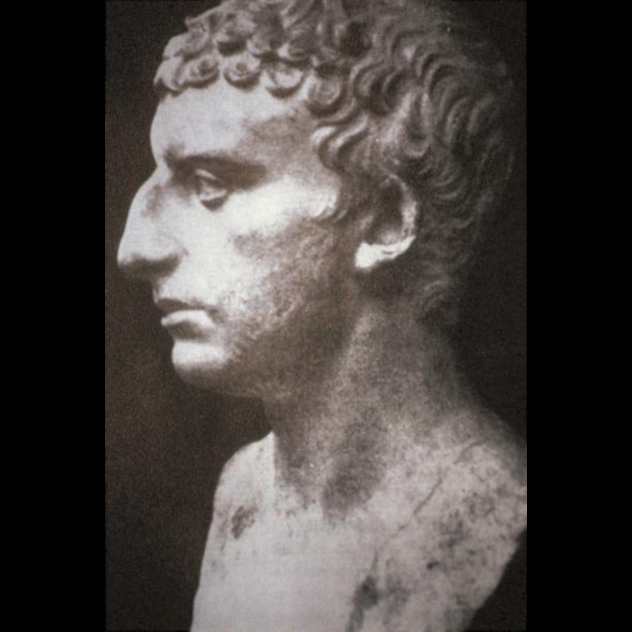

7 Thucydides

The Peloponnesian War

Thucydides was one of the foremost Greek historians, though much of his life is obscured in the fog of antiquity. Ever the self-aggrandizing man, he once wrote that his “history is an everlasting possession, not a prize composition that is heard and forgotten.” He was exiled after a failure on his part to protect the city of Amphipolis from the Spartans. Thucydides then began to compile his great work, History of the Peloponnesian War, the only continuous contemporary account of the fight between Athens and Sparta.

Valuing firsthand accounts above all else, Thucydides included a number of speeches within his writing as well. Perhaps the best known is the funeral oration of Pericles, which some historians suggest may have been an inspiration for Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address, as they share a similar tone, theme, and structure. Though his place in the upper echelon of Western historians was in doubt for much of the time since his death, since the 19th century, his reputation as one of the greatest historiographers has been unassailable.

6 Titus Flavius Josephus

Jewish History (From Adam And Eve To AD 93)

Born into a priestly Jewish family in Jerusalem, Titus Flavius Josephus appeared to be predestined to do something religiously important. In AD 54, at the age of 16, he joined an ascetic Jewish sect and stayed with them for three years, before returning to Jerusalem and becoming a Pharisee. This was an important decision which influenced much of his later life, including his interactions with the Romans, though some sources say that he simply pretended to be a Pharisee, as he was born a Sadducee.

Nevertheless, he began his life as an ardent Jewish man, one who even fought against the Romans during the First Roman-Jewish War, heading up the Jewish forces in Galilee. However, he surrendered to Vespasian, the leader of the Roman forces. He told Vespasian that he felt the Judaic Messianic prophecy was about him and that he was to become emperor. Only a few years later, Vespasian did become emperor, and he rewarded Josephus with Roman citizenship as well as a new name. (He had been born as Joseph ben Matityahu.)

Eventually, an influential Roman named Epaphroditus became a patron of Josephus’s and commissioned him to write his most important works—The Jewish War, which was a collection of books detailing Jewish conflict from 164 BC to 68 AD, and Antiquities of the Jews, which was a 20-volume set of books following the Jewish people from the Garden of Eden straight to Roman rule in AD 93. Though much of the early Jewish history that Josephus wrote about was lifted from the Tanakh, the book has proven invaluable to historians for its description and information about Jewish history for the Second Temple period (580 to 70 BC).

5 Bartolome De Las Casas

Colonization Of The West Indies

Born toward the end of the 15th century, Bartolome de las Casas was a Spanish historian as well as a Dominican friar, a profession which had a great influence on his dealings with the native population of the Americas. At the age of 18, he sailed for Hispaniola, the second-largest island in the West Indies, and was given an encomienda, a land grant that included native slaves, as a reward.

Though he witnessed the brutality of the Spanish settlers firsthand, it took nearly 12 years for de las Casas to have what scholars refer to as his “first conversion.” In 1514, he gave up his rights to his encomienda and began to preach against the system, going so far as to call it a mortal sin. De las Casas spent the next few years sailing back and forth between Spain and the West Indies, trying anything he could to stop the mistreatment of the native population. However, all of his efforts amounted to nothing. Distraught, he abandoned his plans and joined the Dominican Order in 1523 (his “second conversion”).

After serving as a prior for a few years, de las Casas began his writing career, starting with Historia Apologetica, a comparative book defending the native population and arguing that they were just as civilized as any of the great European and Egyptian civilizations. However, his Historia de las Indias was much more influential, and it was twofold: First, it was an account of all the mistreatment inflicted by the Spanish in their conquest and subjugation of the New World. Second, it was a prophecy of sorts, with de las Casas intending to show the Spanish people the punishment that God had in store for them.

Eventually, he reached his goal, and King Charles V of Spain called for the establishment of the New Laws, which required encomiendas to be disbanded after a generation. Afterward, de las Casas was named bishop of Chiapas in Guatemala and wrote a confesionario (or manual), in which he forbade the absolution of those involved with encomiendas.

4 Einhard

Charlemagne’s Real Life

Born in 770, Einhard was sent to a monastery to study at the age of nine. It was there that his intellect was first noticed, and he was eventually sent to Charlemagne’s Palace School at the age of 21. Quickly ascending through the ranks, Einhard became a trusted friend of the king. After Charlemagne’s death in 814, he became even more politically active, helping Louis I the Pious to the throne, an act for which he was rewarded with vast tracts of land and appointment as the abbot of several monasteries.

After Charlemagne’s death, Einhard wrote and compiled his greatest work, Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charles the Great). Described as “one of the most precious literary bequests of the Middle Ages,” it forms the basis for much of our knowledge about the holy Roman emperor and the Carolingian Empire. Wishing to acknowledge a man whose deeds “can scarcely be imitated by the men of our age,” Einhard wrote what is commonly seen as the first biography of a European king. Created in the style of the great Roman biographer Suetonius, especially his biography of Emperor Augustus, Vita Karoli Magni is our source for “almost all our real vivifying knowledge of Charles the Great.” Although many medieval biographies shy away from any negative details about their subjects, Einhard’s book is believed to be a trustworthy document, for the most part.

3 Sima Qian

2,500 Years Of Chinese History

Perhaps the first great Chinese historian, Sima Qian was born in 145 BC, during the Han dynasty. The son of a grand historian in the Han court, he succeeded his father upon his death in 108 BC. The duties of a grand historian (sometimes translated as “royal astronomer”) included observing astronomical events and documenting the daily happenings of the government. Three years later, Sima began to assemble what would become his masterpiece—Records of the Grand Historian, a book which covers Chinese history from 94 BC back to the legendary Yellow Emperor.

However, as it has been throughout human history, trouble was just around the corner. In 99 BC, two military officers failed spectacularly in a campaign in the north and were captured. Though all other government officials condemned one of them (Li Ling), Sima stood alone. Unfortunately, the emperor took offense to this and condemned him to death. At the time, one could pay to avoid execution, either by money or by genitalia. Lacking the necessary funds, Sima chose castration.

Rather than commit suicide, which was customary for those disgraced by castration, Sima Qian chose to finish his work, for which society owes him a great debt. As noted sinologist Jean Levi proclaimed about Sima Qian, “The history of China [ . . . ] is mixed to one degree or another with the history of one man.”

2 Polybius

The Battle Of Carthage (Circa 149 BC)

Although his largest collection of writings, The Histories, deals with the entirety of the rise of ancient Rome from 264 to 146 BC, the Greek historian Polybius’s most valuable contribution is his work on the battle of Carthage, an event for which he was a firsthand witness. Over 50 years old by the time Carthage’s demise, he had spent most of the last 19 years in Rome as a hostage. However, he grew to love the city and befriended a Roman commander named Scipio Aemilianus, a man who would play a large role in the battle of Carthage. So friendly was their relationship that Polybius boasted, “Our friendship and intimacy grew so close that it was well-known [ . . . ]in the countries beyond.”

In 150 BC, after the Third Punic War, all of the hostages were granted freedom and allowed to return to Greece, but Polybius decided to stay with Aemilianus, accompanying him during his siege of Carthage. Certain details of the battle, as well as the aftermath, were recorded only by Polybius, including an account of the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal’s wife committing suicide by jumping into a burning temple after her husband surrendered.

One of the most famous anecdotes in all of antiquity came from Polybius, whose account of Aemilianus after the looting of Carthage is as follows: “Scipio, beholding this spectacle, is said to have shed tears and publicly lamented the fortune of his enemy.” The image of Scipio weeping not only for the destruction of Carthage, but for the future destruction of Rome itself, became the central theme for Polybius’s Histories, namely the mutability of human affairs. As a side note, Polybius never said anywhere in his writing that the Romans salted the earth around Carthage.

1 Kim Bu-sik

Korean History

Though he had plenty of assistance from at least 10 others, Kim Bu-sik is widely recognized as the author of Samguk Sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms), the oldest extant book dealing with Korean history written by a native Korean. Inspired at a young age by China’s major history books, he spent much of his life hoping to write one for his homeland. It didn’t help that any mention of Korea in Chinese literature was brief or inaccurate, and it was impossible to separate fact from fiction.

Spending much of his early life involved with politics and the military, Bu-sik retired at the age of 67, hoping to complete his historical book before his death. Although he was personally responsible for the introductions to each of the 50 books which make up Samguk Sagi as well as personal flourishes throughout, he nevertheless had help, with the bulk of the writing being done by his assistants. Criticized for being too focused on the government, Bu-sik’s writing follows the lives of around 80 historical figures from the three kingdoms of Korea—Silla, Goguryeo, and Baekje. (However, being of Silla origin, Bu-sik was a little biased in his depiction.)