Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Top 10 Intriguing Origins Of School Supplies

Many of us take for granted the tools and conveniences we use in our daily lives. Whether in kindergarten or grad school, students are no exception. Probably few have given any thought to how and why the supplies they use in the course of their studies came about. G.K. Chesterton wrote in his essay “A Piece of Chalk” that had he time enough, he could write “a book of poems entirely about things in [his] pockets.” The same is true of the school supplies that students take with them to class every day, as these ten intriguing origins suggest.

10 Pencil

An ancient Roman writing instrument, the stylus, gave rise to the modern pencil. Some early styluses were made of lead. When graphite was documented in Borrowdale, England, in 1564, the mineral replaced the heavy metal. Graphite left a darker mark on papyrus, but it was so soft that it crumbled easily. To protect the graphite, a holder had to be fashioned for it. The first holders were nothing more than string wound around graphite sticks. Later, hollow wooden sticks replaced the string, and the early modern pencil made its historical debut, its mass production following in 1662 in Nuremberg, Germany.

Although Henry David Thoreau made his own pencils, the first one to be machine-made was manufactured by William Monroe in 1812, when war with England put an end to English imports. By the end of the 19th century, pencils were being mass-produced in the United States. Made of red cedar, they weren’t painted until 1890, the better to exhibit their fine finish. When they began to be painted, bright yellow was chosen because the color is associated with Chinese royalty, and the finest graphite came from China. Yellow pencils signified the royal quality of the mineral.[1]

9 Eraser

In the United States and Canada, it’s an eraser. But in the United Kingdom, India, Ireland, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, the object used to eradicate pencil or ink marks is known as a rubber. Before 1770, when erasers first appeared, many people used small rubber or wax slabs to rub out their penciled mistakes. To eradicate errors in ink, they employed sandstone or pumice. Japanese writers used soft bread to erase pencil marks.

English engineer Edward Nairne was the first to use crumbs of gum elastic, as rubber was then called, instead of bread crumbs, to erase pencil marks. Impressed with its effectiveness, he began selling the material for that purpose. Between 1770 and 1778, the material acquired the name “rubber,” which originated from the action of rubbing.

The problem with early erasers was that gum elastic crumbled easily. It also had an unpleasant odor and was adversely affected by the weather. When Charles Goodyear invented vulcanization to cure rubber, these problems were solved, and rubber gained durability. Erasers were attached to the ends of pencils after Hymen Lipman patented the idea, and the humble eraser took on a bit of personality when novelty versions were later introduced.[2]

8 Ballpoint Pen

Starting in 1888, when American tanner John Loud patented his version of a ballpoint pen to mark hides, over 350 other inventors began patenting additional designs for a ballpoint pen, but none of them saw production. The viscosity, or thickness, of the ink had to be just right: Too thin, and it leaked; too thick, and it clogged. The ink’s viscosity was often at the mercy of the temperature.

In 1935, newspapermen Ladislas and Greg Biro, frustrated by the performance of the fountain pens they used, set out to invent a better pen and to perfect an ink. After a setback caused by their design’s dependence on gravity to feed the ink to their pen’s roller ball, the brothers created a spongy ball that, using capillary action, more easily absorbed ink, allowing the pen to be held at an angle, rather than straight. They made their Biro pen in Argentina, where it didn’t sell well, and they sold the design to the the Eberhard Faber Company for $500,000 sometime after World War II. The company put production on hold, and the patent expired.

Milton Reynolds, a Chicago salesman who’d seen the Biro pen, became a multimillionaire after he began to manufacture the design and sell his product in the United States. Competition became widespread, and extravagant claims for the ballpoint were commonplace. Business boomed—until buyers discovered that the pens still had many flaws.

Patrick J. Frawley went into business with an unemployed chemist, Fran Seech, and they improved the ballpoint’s design, introducing the Papermate pen, which boasted a retractable ballpoint tip and “no-smear ink” that would wash out of fabric. After studying all the ballpoint pens on the market, sometimes microscopically, Marcel Bich, a French manufacturer of penholders, introduced the Ballpoint Bic, and dependable Papermate and Bic ballpoints became staples among students’ school supplies.[3]

7 Highlighter

Before the 1960s, when Japanese inventor Yukio Horie invented a felt-tip pen that used water-based ink, students kept track of important textbook information by making marginal notes and underlining key words and passages. In 1963, Carter’s Ink produced the Hi-Liter, a marker similar to Horie’s pen. Both instruments rely on capillary action to draw ink into their tips. Fluorescent colors were introduced in 1978. Since then, polyethylene beads molded into porous heads have replaced felt tips, and there are retractable and scented models.

Often, since Bibles have especially thin pages, highlighters’ ink seeped through the paper. G.T. Luscombe, a Bible-study materials distributor, solved this problem by introducing highlighters that, thanks to special pigments made in Japan, could mark the Good Book without bleeding through its pages. G.T.’s son, John Luscombe, the president of the family business, said the colors of the Bible markers are associated with various biblical topics: yellow for blessings, blue for the Holy Spirit, pink for salvation, and green for growth and rebirth.[4]

6 Protractor

The protractor has been measuring angles for 500 years. Mapmaker Thomas Blundeville first described the instrument in his 1589 monograph, Briefe Description of Universal Mappes & Cardes. Whether he invented it or not is unknown, as his contemporaries wrote of similar objects. By the early 17th century, protractors were commonly used by maritime navigators. By the 20th century, their use among students in elementary and intermediate schools became prevalent.

The variety of uses for protractors dictates their range of shapes. Protractors made of brass, steel, ivory, and plastic appear in the forms of circles, rectangles, squares, semicircles, quarter-circles (or quadrants), and sixth-circles, with diameters ranging from 5 to 30 centimeters (2–12 in). They may be marked in degrees, half-degrees, millimeters, or inches. Some protractors are combined with rulers, squares, French curves, stencils, circle gauges, templates for drawing basic polygons, and slots for drawing circles. A Japanese protractor exhibited at the 1876 World’s Fair included a notched crossbar and a different character of the Chinese zodiac at each 30-degree mark.[5]

5 Drawing Compass

The drawing compass has been around since ancient times. Specimens of these Roman instruments are housed in the British Museum. Originally, both legs of the drawing compass ended in sharp points so that a circle could be scratched into paper. Later, the circle would be inked. In the 18th century, one leg was adapted to accept a pencil for the graphite tip to draw circles on paper. Compasses can be used by themselves or with a sector.

In the past, drawing compasses were made of a variety of materials, including brass, German silver, aluminum, steel, wood, and plastic. They often featured ornamental design elements. Many were equipped with small knobs on the legs to allow for width adjustments. Americans are typically acquainted with the drawing compass during their elementary school days, but the simple instrument is also a staple among mathematicians, mechanics, and engineers.[6]

4 Three-Ring Binder

German inventor and office supplier Friedrich Soennecken invented the ring binder in 1886. Later, two holes in the side of the binder were added, 80 millimeters apart from one another, setting the standard distance between these openings.

When loose-leaf paper appeared in 1854, Henry T. Sisson of Rhode Island invented the two- and three-ring binders, but they weren’t mass-produced until 1899, when the Chicago Binder and File Company began to sell the product. Although D-ring binders and four-ring binders appeared half a century later, the three-ring version remains the most favored by today’s students.[7]

3 Paper Hole Reinforcements

Although loose-leaf paper was invented in 1854, Kenneth J. Russo and George Block didn’t patent paper hole reinforcements until 1992. Today, the circular adhesive labels with punched-out centers often come in sheets, but originally, they were mounted on rolls. They were designed for use in hospitals and other institutions in which “there is a great demand for removable record sheets” because of the wear and tear such documents typically receive.

Prior to Russo and Block’s reinforcements, fabric or plastic with glue on their mounting sides was used to strengthen paper holes. The mounting sides were covered with a backing, which was difficult to remove. Pressure-sensitive reinforcements lacked such a backing, making them easier to use than their fabric and plastic predecessors. The reinforcements, available in either transparent or opaque plastic or in polyethylene, polyester, acetates, or polystyrene, were packaged on rolls in configurations designed to align with the holes in standard three-ring and five-ring binders. Although they were thin, they had a “preferred” tensile strength of 70 pounds per square inch. In school, they were handy in preserving assignments students didn’t want to lose and have to complete anew.[8]

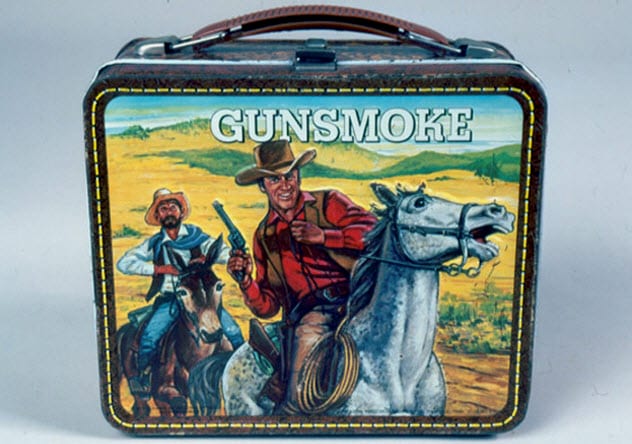

2 Lunch Box

Lunch boxes started out, late in the 19th century, as lunch pails. As the name suggests, they resembled buckets, but they were equipped with lids. Later designs were still metal, but they were shaped more like breadbaskets than pails, and many featured clasps by which their lids could be opened or closed. Students began to carry their own lunch boxes to school, just as their fathers took theirs to work.

The first commercial lunch boxes appeared in 1902 and were designed to look like picnic baskets. Perhaps to indicate the product’s intended consumer, images of children frolic about the containers. Mickey Mouse lunch boxes were the rage in the 1950s. One of them, painted to resemble a school bus, bore Mickey and friends like Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Goofy.

Lunch boxes, many manufactured by Thermos, often related to television programs. Over the years, Gunsmoke, Lost in Space, Julia, and The Partridge Family were popular. Others capitalized on Barbie, the Beatles, and the Harlem Globetrotters. As TV shows came and went, lunch boxes reflected this change, with Woody Woodpecker, Kung Fu, and Knight Rider appearing on retailers’ shelves.

120 million lunch boxes were sold during their heyday (1950–1970), but today, students favor soft, insulated polyester versions that can easily be placed in backpacks. But the lunch box hasn’t become extinct yet. In fact, it’s currently enjoying a revival. Merchants are selling lunch boxes again, sometimes as “reissues of classic designs” and sometimes as “new but with a retro look.”[9]

1 Backpack

Backpacks haven’t been around for very long. Before their advent, students strapped stacks of books together and carried them at the end of leather or cloth thongs. Alternatively, they carried them by hand, boys slung under their arms, girls cradling them as though they were babes in arms. In 1938, outdoor clothing and gear retailer Gerry Outdoors invented the first zippered backpack, but students weren’t interested in them at the time. They sold mostly to campers, hikers, and skiers. Students stuck with straps or used small briefcases called satchels.

Backpacks haven’t been around for very long. Before their advent, students strapped stacks of books together and carried them at the end of leather or cloth thongs. Alternatively, they carried them by hand, boys slung under their arms, girls cradling them as though they were babes in arms. In 1938, outdoor clothing and gear retailer Gerry Outdoors invented the first zippered backpack, but students weren’t interested in them at the time. They sold mostly to campers, hikers, and skiers. Students stuck with straps or used small briefcases called satchels.

Gerry Outdoors also created the first modern nylon backpack in 1967. It was an instant hit among people who enjoy outdoor life. But students didn’t take to the backpack until JanSport marketed their own lightweight version and University of Washington students adopted the practice of using them to carry their textbooks and school supplies. The backpack was soon used by public school and college students nationwide. To keep up with the times, backpacks have since become smaller and are equipped with multiple pockets and pouches for smartphones, laptops, and accessory equipment.[10]

Gary Pullman lives south of Area 51, which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His 2016 urban fantasy novel, A Whole World Full of Hurt, available on Amazon.com, was published by The Wild Rose Press. An instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, he writes several blogs, one of which is Chillers and Thrillers: A Blog on the Theory and Practice of Writing Horror Fiction.

Read more about the origins of every day things 10 Disney Movies With Horrific Origins and Top 10 Famous Companies With Unexpected Origins.