Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Fascinating Stories From Legendary Mercenaries

It is a common refrain that prostitution is the oldest profession in the world. If that is true, then the second oldest is being a soldier-for-hire. Mercenaries have always been a part of warfare, and even though national armies, whether predicated upon voluntary professionals or conscripts, have ruled the battlefield since the 18th century, mercenaries haven’t gone anywhere. In fact, mercenaries (otherwise known by the more antiseptic term “private military contractors”) have enjoyed a renaissance since the 2003 war in Iraq. Most recently, in late 2017, Erik Prince, former US Navy SEAL and the founder of Blackwater, wrote an editorial suggesting that the war in Afghanistan could be won by replacing thousands of American troops with military contractors.[1] The idea was not accepted by the Trump administration, but it got a serious hearing.

Mercenaries and privateers (the seaborne version of a mercenary) have been responsible for some of the greatest triumphs and darkest deeds in the history of warfare. Stories about these men have dazzled readers for centuries. The exploits of history’s mercenaries can also tell us a lot about human interactions and how mercenaries were some of the first people to cross cultural barriers and interact with different civilizations.

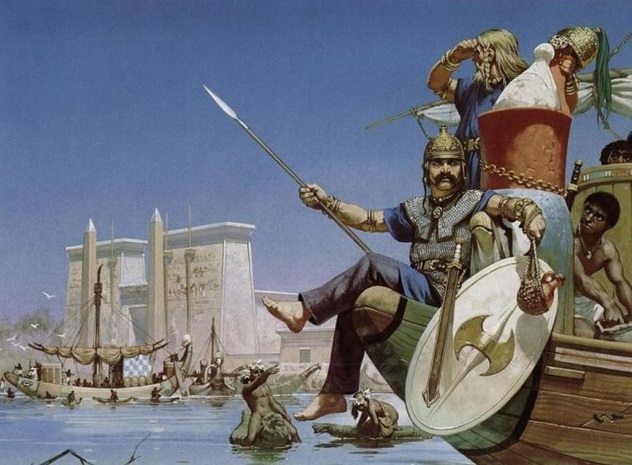

10 The Celtic Mercenaries Of Egypt

Ancient history makes it clear that some tribes and peoples have always been considered warlike. Between the Western Roman Empire and the end of the Early Modern Era, Europe’s most feared mercenaries were German-speakers from the Holy Roman Empire or Switzerland (more on some of these men later). However, prior to this epoch, Europe’s most sought-after warriors were the Celtic peoples of Gaul (France), Northern Italy, the Balkans, and the British Isles.

Beginning in the fourth century BC, Celtic tribes began raiding the city-states of the Mediterranean. In 390 BC, Celtic warriors sacked an Etruscan city on the Tiber River.[2] Thus began a long feud between the Celts and the people of the Italian Peninsula. This feud would reach its apogee on July 18, 387 BC, when Gallic tribesman led by Brennus defeated a Roman army and sacked Rome, taking with them slaves, women, and gold.

Word quickly spread concerning these fearsome red- and blond-haired warriors from the north. The Greek city-states of Syracuse and Sparta often employed Celtic mercenaries to fight their battles, and the Carthaginian general Hannibal also used Celts in his army during the Second Punic War.

Celtic mercenaries saw fighting outside of Europe, as well. During the reign of the ethnically Greek Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, Celtic mercenaries were often hired as part of the kingdom’s official army. Many of these Celts came from the tribes of Eastern Europe and Galatia in central Anatolia (today’s Turkey). During the reign of Pharaoh Ptolemy III Euergetes, Celtic mercenaries played a decisive role in conquering Syria and Judea and defeating the armies of the Seleucid Empire, another ethnically Greek kingdom in Asia. The Greek historian Polybius even recorded that many Celtic mercenaries settled in Egypt and took Egyptian or Greek wives. To the Greeks, these Celto-Mediterranean children became known as e pigovoi.

9 The Wild Geese

The so-called “Wild Geese” of the 17th and 18th centuries are in many ways the direct heirs of the ancient Celtic mercenaries of the Mediterranean. Following the Treaty of Limerick in 1691, which ended the Williamite-Jacobite War in Ireland, Irish Jacobite general Patrick Sarsfield agreed to let as many as 20,000 Irish Catholic troops board French ships and become mercenaries in Europe. Like their Celtic forebears, these battle-hardened troops were known for their toughness and were considered to be the best light infantry force on the continent. The Irish soldiers of Sarsfield later became known as the Wild Geese, and their Catholic fighters would serve honorably in the armies of France, Spain, and Russia.

Irish mercenaries had served in Habsburg Spain since at least the 1580s, when the English crown sent rebellious Catholics to Spain as a way to both fight the Spanish and keep Ireland quiet. Unfortunately for London, many of these Irish soldiers pledged allegiance to Spain and fought against English and Dutch armies. Irish soldiers in Spain would see service later against Napoleon, while during the apex of the Spanish Empire, Irish mercenaries saw action in Mexico and South America.[3] Many of these Irish mercenaries would establish noble families in the New World, and as a result, several leaders of the Latin American independence movements turned out to be ethnically Irish. (See, for instance, Bernardo O’Higgins of Chile.)

The Wild Geese truly earned their fighting reputation in France. The Irish Brigade of King Louis XIV’s army would fight in the War of Spanish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession, and the Seven Years War. Irish mercenaries also fought for the Spanish-French forces against the British during the siege of Pensacola, Florida, in 1781.

8 American Mercenaries In China

Americans of all stripes have long taken an active role in Chinese affairs. During the 19th century, American Christian missionaries, doctors, and school teachers were all over China, especially in coastal cities like Shanghai, Tientsin (Tianjin), and Tsingtao (Qingdao). Another group of Americans came to China as mercenaries either in the employ of the Qing Dynasty or the various warlords who came to power following the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912.

Notable American mercenaries in China included Homer Lea and Philo McGiffin. Lea was a native of Colorado who became interested in Chinese affairs after befriending Ng Poon Chew in Los Angeles’s Chinatown. Seeing in China a chance for glory and adventure, Lea learned Cantonese, joined a secret society, and began training Chinese men for military service in China while they lived in California. In 1899, the Stanford-educated Lea joined an army loyal to the warlord K’ang Yu-wei and stayed in China until Empress Dowager Tz’u Hsi began reforming the Qing monarchy along Western lines. Lea would later befriend Dr. Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong, and in 1909, his book, The Valor of Ignorance, predicted that a militarily aggressive Japan would try to conquer America by attacking the Philippines and Hawaii.

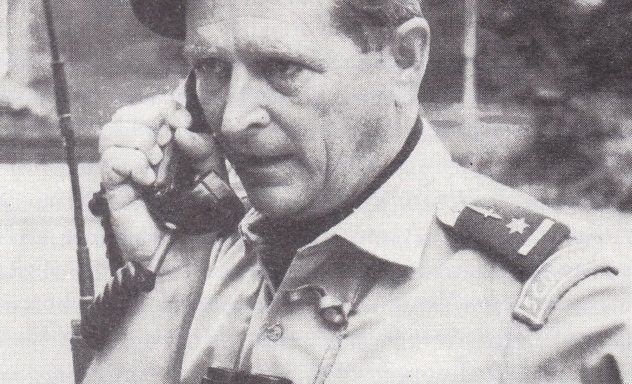

Philo McGiffin was born in Pennsylvania to a family with a long history of fighting in America’s wars. McGiffin attended the US Naval Academy at Annapolis but failed to attain an officer’s commission due to poor test scores. Still seeking to put his naval skills to use, McGiffin sailed to Tientsin during the Tonkin War (1884–1885) and volunteered for the Imperial Chinese Navy. After serving as an instructor at the Chinese Naval Academy, McGiffin was an officer aboard the Chinese battleship Chen Yuen during the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894. Although the Japanese fleet destroyed its Chinese foe, McGiffin’s battleship managed to fight on for hours without sinking.[4] McGiffin is pictured above recovering from wounds sustained in the battle.

The most famous American mercenaries to ever serve in China were the members of the First American Volunteer Group, or “Flying Tigers,” who served as members of the Chinese Air Force between 1941 and 1942.

7 The Mercenary Revolt In Brazil

Because most of them fight for nothing more than money, mercenaries have shown a propensity to engage in unruly behavior. This is certainly what happened in 1828, when Irish and German mercenaries revolted against the Empire of Brazil, the very government that had hired them in the first place.

The roots of this revolt originated in the Cisalpine War between Brazil and the United Provinces. By July 1828, Brazilian war-weariness was at an all-time high, thanks to several military defeats. Incensed that the terms of their contracts had not yet been met, two battalions of Irish and German mercenaries revolted and took control of a large swath of the city of Rio de Janeiro.[5]

Unsurprisingly, violence was used to put this revolt down. A force of 300 Brazilians, 300 French sailors, and 224 British Royal Marines managed to suppress the revolt by killing approximately 150 of the mercenaries. Many of the Irish who survived were sent back to their homeland, while a large percentage of the Germans were sent to live in the remote provinces of Brazil.

6 Swiss Mercenaries

Today, Switzerland is synonymous with its pacifist foreign policy. Switzerland simply does not fight wars. However, Swiss mercenaries have been fighting on battlefields since the Middle Ages. The first written accounts of Swiss mercenary companies date from the 13th century, but the fearsome Swiss soldiers of Europe did not become infamous until the 16th century. At that time, Swiss mercenaries fought in the army of King Louis XII of France during the Italian Wars. Between 1516 and 1793, Swiss mercenaries almost exclusively served the French throne as part of an unofficial agreement.

The most elite of these Swiss mercenaries were the pikemen. Usually formed into phalanxes, Swiss pikemen used 6-meter (20 ft) spears to devastating effect. In 1386, 1,200 pikemen defeated a Holy Roman army of 6,000 soldiers who had invaded Swiss territory. In 1444, at the Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs, the French army of King Louis XI was routed by 1,200 to 1,600 Swiss pikemen.[6] This was despite the fact that the Swiss were outnumbered 15–1.

Recognizing that mobile formations of battle-hardened Swiss pikemen could defeat almost any European army, France and Austria employed them to great effect. Swiss pikemen helped the Spanish and Holy Roman forces to take Milan in 1525. The notoriety of the Swiss pikemen also encouraged the Vatican to hire Swiss mercenaries. The Swiss Guard, a body of Swiss Catholic soldiers, was officially formed in 1506 and still serves the papacy to this day.

5 The Black Army

It was a mostly mercenary army that turned the Kingdom of Hungary from a backwater into one of the most powerful states in Christendom. The Black Army was the idea of King Matthias Corvinus (Matyas Corvinus), the so-called “Renaissance King” who was known for his large library, his scientific work, and his excellent statecraft. Realizing that Hungary needed a skilled military to protect itself from the growing power of the Ottoman Turks, Corvinus taxed Hungarian nobles in order to raise a force of 30,000 mercenaries. These fighters came from Bohemia, Austria, Poland, Croatia, Serbia, Bavaria, and Switzerland. Until Corvinus’s death in 1490, the Black Army ruled Central Europe as the premiere fighting force in the Balkans and Eastern Europe.[7]

The Black Army would eventually lose power in Hungary thanks to the tax legislation of the 16th century. Before that, the Black Army won several notable victories, witnessed several mutinies, and was one of the first European armies to embrace a terrifying new technology—the firearm.

4 The White Legion

In the modern world, Africa has seen the most mercenary activity. Since at least the late 19th century, several African colonies and states have employed foreign nationals to serve as mercenaries in the continent’s many bush wars. One of the more infamous mercenary units was the White Legion of the First Congo War.

The White Legion consisted of about 200 Eastern European mercenaries who served on behalf of the Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko.[8] The White Legion primarily guarded the important city of Kisangani. By 1997, it was clear to all observers that Mobutu would not be able to hold on to power, and therefore, the White Legion left the country in that same year after several insignificant battles.

Although the White Legion played no role in the outcome of the First Congo War, their presence on the battlefield did speak volumes about how globalized the mercenary trade had become. The White Legion mostly came from the former state of Yugoslavia, and more specifically, a majority of these mercenaries had once served under the Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladic. Mladic was nicknamed the “Butcher of Bosnia” for his gruesome exploits during the Bosnian War of the early to mid-1990s. In 2017, Mladic received a life sentence for war crimes.

3 The Eagle Of Brittany

Arguably the best-known mercenary of the medieval world is the Englishman John Hawkwood, the leader of the White Company. Another great warlord of medieval Europe was the Breton knight Bertrand du Guesclin, a man so fearsome that he was nicknamed the “Eagle of Brittany” and the “Black Dog of Broceliande.”

Guesclin was born in 1320, and he first saw serious action in the 1340s. At that time, Guesclin fought for the House of Blois against the House of Montfort. Known as the War of Breton Succession, this inter-noble fighting ended in a victory for the Montfort family. At the Battle of Auray, Guesclin was captured by the Anglo-Breton army and ransomed for 100,000 francs. Following his release, Guesclin briefly left France in order to fight as a mercenary in Spain under the command of Count Henry of Trastamara, the future King Henry II of Castile and Leon.

Guesclin saw heavy action during the Castilian Civil War, and his “free company” (a medieval term for mercenaries) helped to win the day at the Battle of Montiel in 1369. A year later, French king Charles V recalled Guesclin back to France in order to fight the English army. In that same year, Guesclin was named as the constable of France, the highest military position at that time.[9] Under Guesclin, French soldiers and mercenary bands frequently defeated the English by employing the Fabian strategy, or the art of avoiding pitched battles in favor of small skirmishes.

2 The Landsknechts

The most controversial, yet most successful, mercenary unit of the Early Modern Era was the Landsknechts, an almost exclusively German force from the mountainous states of the Holy Roman Empire. During the 16th century, the Landsknechts were known for their bloodthirsty ways and their often disloyal behavior. (It was reported widely at the time that Landsknecht soldiers would switch sides during battles.)

What is known about the Landsknechts for sure is that they were created by the Holy Roman emperor Maximillian I. Inspired by the Swiss pikemen used by the French army, Emperor Maximilian began recruiting tough men from places like Swabia, Alsace, Tyrol, and the Rhineland. These men literally stood out on the battlefield because they were exempt from clothing regulations, thus Landsknecht soldiers became easily identifiable due to their flashy and bright clothing.

At the height of their power, the Landsknechts utilized such weapons as the halberd (a poleaxe), a two-handed sword called the zweihander, and the arquebus long gun to defeat better-trained and larger armies.[10] At the battles of Bicocca and Marignano, the Landsknechts defeated the Swiss pikemen. Like their adversaries, the Landsknechts employed squares of pikemen, but these pikemen were flanked by supporting troops armed with halberds, guns, and swords. The Landsknechts also used a tactic called the forlorn hope, whereby swordsmen would run in between pikemen in order to disrupt battle formations.

By the time of the Protestant Reformation, many of the Landsknechts had become Lutherans. However, this did not stop many from serving Catholic masters. Similarly, the Landsknechts were not known for their Christian behavior. They almost always traveled with prostitutes, drank hard, and were known to rape and pillage cities if their pay was late. The Landsknechts can easily be summed up by the motto used by their most famous commander, Georg von Frundsberg: “Many enemies, much honor.”

1 5 Commando

Following the declaration of independence from Belgium in 1960, the Congo dissolved into a horror show of insurgent warfare and racial violence. The left-wing radical Patrice Lumumba tried to become the strongman of the country by squashing all nascent federalist and independence movements. The strongest anti-Lumumba force was the State of Katanga. Katanga was the most economically dynamic part of the Congo, with numerous copper mines and large reserves of cobalt and diamonds. Katanga’s leader, Moise Tshombe, was a Christian whose pro-European stance earned him the support of Congo’s white population. During the 1961 siege at Jadotville, the Irish soldiers of the UN met violent resistance from many of the whites who had moved to Katanga in order to escape the anti-white pogroms that began during an army mutiny in Stanleyville in 1960.

Three years later, in Northeastern Congo, a group of young communists called the Simbas revolted against the central state and took over almost 50 percent of the entire country. Since the Congolese Army proved so inept, Prime Minister Tshombe (Lumumba had been assassinated in 1961) hired approximately 300 mercenaries under the command of Mike Hoare. Known as “Mad Mike,” Hoare had served in the British Army in India and Burma during World War II. After the war, Hoare moved to South Africa and became a big game hunter and mercenary.

Taking inspiration from the Wild Geese, Hoare created 5 Commando, a pro-Tshombe force of white mercenaries drawn mostly from the Boer population of South Africa. (Even today, white South Africans serve as mercenaries all across Africa.) 5 Commando, along with other mercenary units, successfully put down the Simba rebellion by 1965. 5 Commando is one of the most well-documented mercenary units because several journalists, including the South African Hans Germani, served in the unit and documented its many battles against the genocidal Simbas.[11]

The legacy of 5 Commando was cemented with the 1978 action film The Wild Geese, which Hoare worked on as a technical consultant. Many of the veterans of Hoare’s unit would go on to serve in the Rhodesian Bush War and the many insurgency wars between apartheid-era South Africa and its neighbors.

Read more mercenary exploits on 10 Swashbuckling Mercenaries Who Ravaged Medieval Europe and 10 Movie Worthy Real-life Mercenaries.