Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

10 Bizarre Dishes on Victorian Dinner Tables

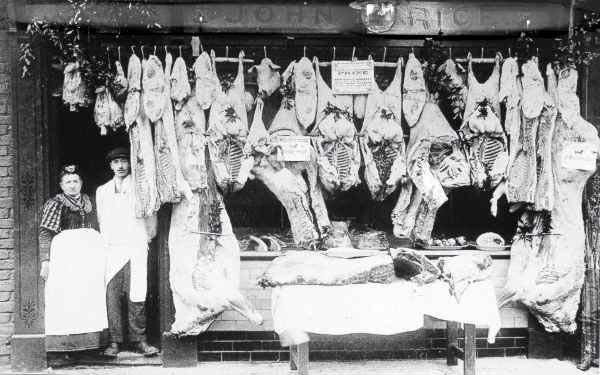

The Victorians didn’t just carve off steaks and chops from cows, pigs, sheep, etc., and dump what was left of the carcasses into a sausage grinder. Embracing the whole critter from snout to tail, they enjoyed offal and other bits that normally go into hot dogs. Brains, tripe, tongue, head, feet, tail, ears … you name it, a nineteenth century cook knew what to do with it.

The dishes on this list can be found in many cookbooks of the period on both sides of the Atlantic. If you enjoy offal, you’ll probably be reaching for a knife, fork, and napkin when you get to the end of the list. The rest of us will be over there, cherishing our desperate self-delusion that hot dogs come from some mysterious region of meaty, non-wobbly goodness on the cow and/or pig that’s just missing from the butcher’s diagram.

Bon appétit!

This is exactly what it sounds like. A calf’s head was purchased from the butcher, who often left it up to the cook to clean off the hair and tidy it up before popping the head into a pan and boiling until tender. The tongue was removed, cut into slices, and arranged on a platter with the picked flesh. The eyeballs were cut in half and included—not as garnish, but a delicacy. The dish was served with the brains minced into a sauce, if you were getting the nice version. Otherwise, if it was just family for dinner, you might have the pleasure of the entire steaming head, jellied white eyeballs and all, plunked down in front of you.

Considered the proper food for invalids, this aspic-type dish was prepared with a calf’s head and calves feet boiled a long time and strained. The cooked calf’s brains were added, and the jelly clarified, and strained again into a mold or bowl and cooled. The unappetizing, grayish jelly was supposed to be congealed enough to slice. As a treat, you might arrange the brains and a few boiled egg slices on the bottom of the mold before you poured in the jelly. This is not unlike head cheese, except the dish contains little actual meat.

It’s not the dish itself that’s necessarily weird, but the method of preparation doesn’t sit well with modern sensibilities. Victorian cooks believed most types of fish simply didn’t have firm flesh unless they were crimped—that is, had large, deep gashes cut into their sides with a knife while they were still alive and struggling. Cod were especially targeted for this treatment. Even then, the practice was considered cruel. Nevertheless, chefs and cooks alike continued to crimp fish and skate, though as the century turned, it became less commonplace.

A simple recipe: one first makes a brown roux by cooking butter and flour in a pan. Add boiling water, salt, and caraway seeds, stirring until smooth. Voilà! Soup. Another variation substitutes nutmeg for the caraway. I can only imagine the desperation and empty cupboard of the cook who had to serve this dish. While “mehlsuppe” is a traditional soup of Switzerland, modern recipes include such tasty things as onions, chicken or beef stock, and grated cheese like Parmesan. Nineteenth century dinner guests received a literal flour soup.

Related to #10 on the list, this was not a euphemism, but a pig’s head, boiled for hours with cow’s heels, and rubbed with salt before being brined for several days. The brine was flavored with lemon or lime, pepper, and a touch of cayenne. The dish of snout, ears, eyes, grinning jaw, etc., was served with mustard and vinegar to those with a hearty appetite for pickled meat. If a daintier dish was desired, after the brining, the meat was removed from the bones, chopped, placed in a stoneware jar or mold, and the strained liquid from the original cooking poured over and cooled until set. Not unlike a modern brawn.

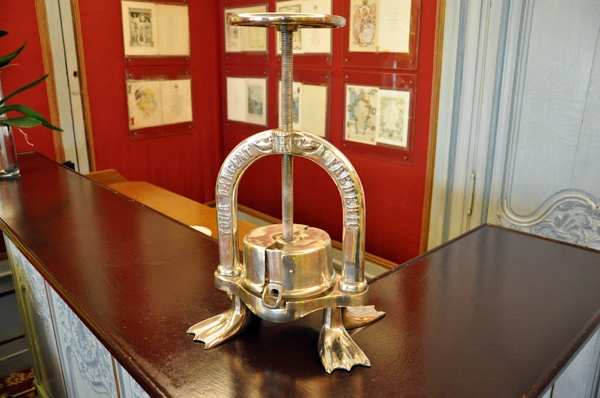

First, you need to strangle your duck. Once again, this isn’t a euphemism. The duck was strangled instead of decapitated to preserve the bodily fluids. To continue the preparation, the duck was semi-roasted, the legs, breast, and liver removed, and the rest of the carcass crushed in a special press to squeeze out the blood and juices, which were made into a sauce served over the reserved meat. The dish was created at the Tour d’Argent restaurant in Paris. It didn’t take long for duck presses to make their way into home kitchens. If you’re curious and happen to visit Paris, the specialty dish is still on the restaurant’s menu.

A soup of the “waste not, want not” variety. Essentially, one took a bunch of miscellaneous small fish, such as anything that might be left at the end of the fisherman’s day, and boiled them in water with parsley roots, a bit of wine, and some vinegar if available. The resulting soup was thin, green, and fishy. If freshwater fish were used, care had to be taken to avoid the soup tasting like mud. The fish weren’t boned, by the way, so a degree of caution when eating was required. An upscale version consisted of chunks of bigger fish cooked in much less water, and flavored with bouquet garni and leeks. More of a rustic stew.

Before you ask, no, this isn’t the name of a porn film extra. Game such as venison and game birds like pheasant, grouse, partridge, etc. were hung up to age and improve the meat’s flavor and tenderness. Victorians liked their meat very well hung, indeed. Recommendations for hanging pheasant ranged from 6-7 days, or until blood ran out of the beak (via Louis Eustache Ude, The French Cook) to hanging from the feet until they dropped off. No refrigeration, so you can guess the inevitable result. Some preferred their meat or bird hung until it went green and maggoty. Meat is still hung today, though under much cleaner conditions, but a few hunters still like their dinner so gamey, it tries to crawl off the plate.

A meat for those who couldn’t afford better, broxy was the name given to diseased sheep that had dropped dead of an illness. The butchered animals were sold in lower class shops. Broxy was much cheaper than mutton, and eaten by the rural and urban poor. Having broxy for dinner meant rolling the dice against a worse outcome than an upset tummy or heartburn. Among the sheep sicknesses that affect humans are tetanus, toxoplasmosis, scabby mouth disease, salmonella, cryptosporidia, ringworm, Q-fever, and campylobacter infections.

When cows or sheep are slaughtered, if they’re pregnant, they often spontaneously abort the fetus when they die, or the fetus is removed when the carcass is processed. Victorian butchers offered these aborted calves and lambs to their customers (and farmers to their families and employees) as slink veal or slink lamb, a protein for those who couldn’t afford better cuts of meat. A unique, taboo, somewhat legendary delicacy from Anglo-Indian cuisine is kutti pi, a slow braised goat fetus. Apparently, the undeveloped bones are soft and can be eaten with the meat, which has a mouth-feel similar to liver, or so I’ve read.

Nineteenth century diners weren’t quite as picky as us, and the cuisine reflected their all-inclusive tastes. What to eat didn’t mean choosing between a pizza delivered to the house or sticking frozen taquitos in the microwave. At mealtime, you usually found yourself at the table staring down at your dinner … and sometimes, dinner stared right back at you.