Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Ten Groundbreaking Tattoos with Fascinating Backstories

Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

10 Lesser-Known Disasters of the 20th Century

Disasters, whether natural or manmade, leave scars on the landscape and the victims. Time passes, the wounds heal, and the event slowly fades from public consciousness. Here are 10 disasters which happened in the 20th century that may not be so very well known today.

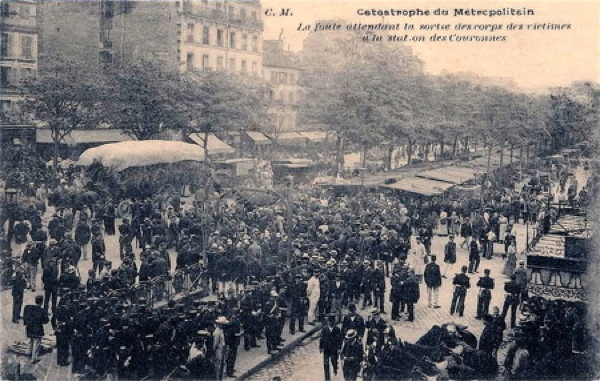

The Paris Métropolitain—the city’s underground mass transit system—opened for business in 1900. By 1903, certain problems were well known: the train carriages were made of wood and posed a fire hazard, the tunnels had no ventilation, and exits at the stations hadn’t been designed to accommodate the increasing number of passengers. In August of that year, these factors combined to create a deadly chain of events ending in the deaths of 84 victims.

It began when a train bound for Ménilmontant suffered an engine breakdown. Another train hooked up to act as a pusher. Passengers from both trains were stuffed into the carriages of a third, which was already crowded. As the first train was being pushed toward Les Couronnes station, faulty wiring in the electric motor began to spark, creating a small fire. However, rather than stop, the driver of the second train accelerated, hoping to reach Ménilmontant station to take care of the fire.

The increased flow of air fanned the flames. When the trains almost reached Ménilmontant, the first train’s engine exploded in a fireball that quickly engulfed the wooden carriages of both trains. The crews fled into the darkened tunnel as the lights blew.

About thirty yards behind, the third train’s passengers were warned by guards to evacuate. They were left to grope their own way in the dark, choking on smoke, either forward to Ménilmontant or back through the tunnel to Les Couronnes. Unfortunately for passengers who chose the latter, the station hadn’t been closed to the public. A rush hour crowd coming into Les Couronnes blocked any hope of escape. Panic set in.

By the time fire fighters reached the scene, bodies were piled as high as the ceiling on the Les Couronnes platform. Most victims succumbed to smoke inhalation. Bricks had been scratched and torn off the walls by dying victims desperate to claw their way out. More bizarrely, eleven more victims were discovered at the ticket office, where they had smashed the windows in an attempt to get a refund for their one penny fare.

In the aftermath, four trainmen were convicted.

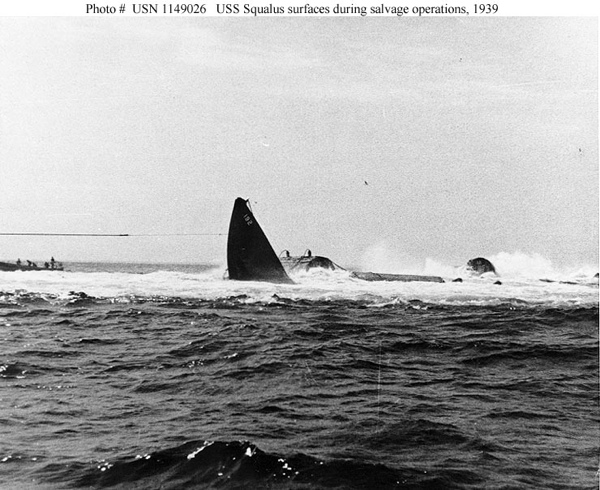

SS-192, also known as the USS Squalus, was a Navy submarine on testing maneuvers in the North Atlantic, 15 miles from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, when disaster struck. While subsequent events led to about half the crewmen losing their lives, including two civilians, the survivors’ fate would hang on a historic rescue.

During a test dive to the southeast of the Isle of Shoals, a valve failure at the fifty foot mark, causing catastrophic flooding in the Squalus’s engine compartment. The submarine sank quickly, coming to rest on the bottom of the ocean, 243 feet down. Apart from both engine rooms, the forward battery also flooded. The 33 crewmen located in the control room and the forward torpedo room were the only survivors.

After deploying a telephone buoy (the cord broke) and firing rockets, the survivors settled down to conserve the scanty air supply in the dark, with only handheld lanterns for illumination. Meanwhile, slow leaks continued to plague the downed sub. The crew had no choice except to wait for rescue. At such depth, their emergency escape gear—individual re-breathers called Momsen Lungs—might not work.

Once naval authorities in Portsmouth realized Squalus had stopped responding over the radio, ships were sent to investigate. A rescue operation began using divers and a rescue bell. The 5×7 chamber was equipped with oxygen lines, a phone, and two operators, and was attached to one of the submarine’s hatches by divers. Survivors were taken off the Squalus in small groups of no more than nine men. Just after midnight on May 25, the crew’s 29-hour ordeal ended with the last survivors taken to the surface.

Months later, in a second operation, U.S. Navy divers attached pontoons to Squalus to raise the submarine off the ocean floor. After much difficulty, 113 days after the disaster, the submarine was towed into Portsmouth Navy Yard. In May 1940, the repaired sub was re-commissioned as USS Sailfish and served during WWII until decommissioned in 1945.

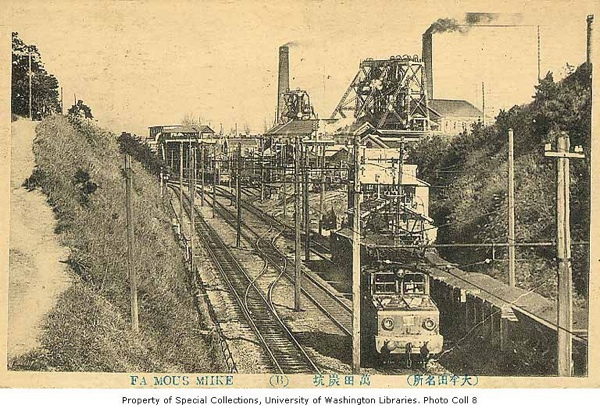

On the southern island of Kyushu, in the Mitsui Miike underground coal mine, a horrific explosion tore through the tunnels. The blast killed some miners instantly and left others to suffocate in the dark in the worst postwar disaster suffered by Japan.

More than 1,300 workers were underground during a shift change when an accumulation of coal dust in the air ignited, causing a tremendously powerful explosion about 500 yards from the entrance. While the mine had some safety procedures in place to prevent such accidents, labor disputes, mass layoffs, and other management decisions meant to reduce production costs, including fewer safety personnel, resulted in these procedures being neglected. The work areas also lacked proper ventilation systems.

The explosion caused several tunnels to collapse. Worse, carbon monoxide began to build up to highly toxic levels. Some workers managed to escape to other nearby mines through connecting tunnels. Others attempted to help injured men find a way outside, but many were too ill or weak from breathing carbon monoxide to save themselves.

Due to management delays and blunders, rescue operations didn’t begin until 6:30 P.M., more than three hours after the accident. Rescuers found at least a hundred bodies next to the personnel carrier at the entrance. In total, 458 people lost their lives and more than 800 suffered the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning.

The company’s bad safety track record didn’t improve much—a mine fire in 1984 took the lives of 84 workers. After the incident, 19 officials were charged with negligence.

Weather can be mystifying, variable, unpredictable. At the end of February and early March 1938, a storm began that would result in the worst flooding in Southern California in nearly a century. The continuous, five-day deluge saturated Los Angeles, Riverside, and Orange Counties and caused rivers to swell over their banks from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach, causing massive property damages, injuries, and deaths.

In the San Gabriel Mountains, gates opened to save the Big Tujunga Dam released more flood waters. Movie studios became islands in the middle of lakes, and stars were trapped in their ranches in the valleys, forcing a delay in the Academy Awards ceremony.

In Universal City, the raging flood washed away the Lankershim Boulevard Bridge, killing five people. Railway lines, other bridges, and roads were washed out. Telegraph and telephone lines went down. Towns and farms in low-lying areas were underwater. In downtown Los Angeles, people claimed to find perch swimming in the gutters. Radio broadcasters reporting on the flooding exaggerated their claims, causing panic to worsen.

Eleven inches of rain fell in five days and the rivers continued to rise. Victims continued to be swept away by the floods. By the time the flooding ended, approximately 115 people were dead, thousands were left homeless, and damages ran into the multi-millions.

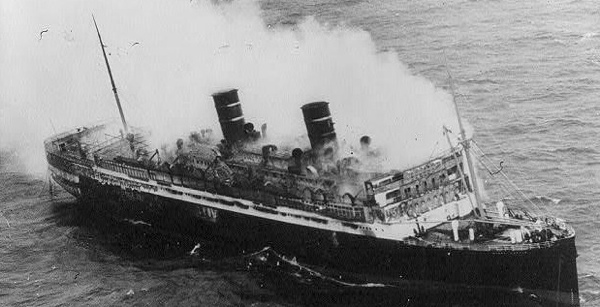

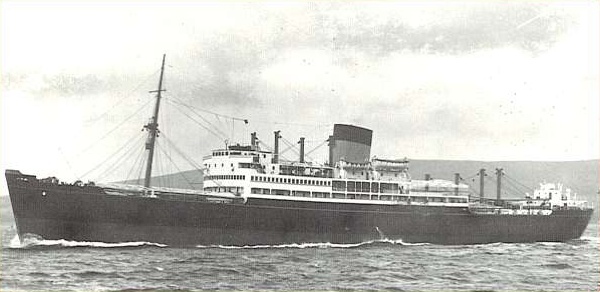

A new, fast, and modern turbo-electric liner operated by the Ward Line, the SS Morro Castle—nicknamed the “millionaire’s yacht” and considered one of the safest ships at sea—shockingly went down in flames in one of the worst peacetime disasters in U.S. history.

Several factors contributed to the accident. To ensure maximum profits during the Depression, the Morro Castle had to make its run between New York City and Havana, Cuba as often as possible, with very little to no down time allowed for maintenance. High crew turnover meant many were unfamiliar with safety procedures. And due to a lawsuit filed by a passenger against the Ward Line, Captain Wilmott ordered emergency drills discontinued. The captain also showed signs of paranoia and growing illness during the ill-fated trip.

The night before docking in New York, Wilmott was found dead in his cabin, victim of an apparent heart attack according to the ship’s doctor. First Officer William Warms—not known by passengers or respected by the crew—assumed command and attempted to navigate Morro Castle through a terrible storm in near hurricane strength gusts.

Around 3 A.M. a crewman reported smoke coming from a small passenger lounge. An officer investigated and found a fully fledged blaze. After a delay, untrained crew members attempted to put out the fire, but didn’t know how to properly work the equipment. By the time Warms, distracted by the storm, ordered passengers into the lifeboats, many were too terrified or intoxicated to evacuate, and the fire continued spreading. Sending an SOS was delayed by nearly a half hour while the radio operators waited to hear from Warms.

The fire burned out of control. Warms steered Morro Castle closer to the New Jersey shore, to a position five miles off the coast of Manasquan. Panicked passengers blackened by smoke and flames leaped off the deck into the cold, storm tossed water. Only six of the ship’s lifeboats were deployed, most of them carrying mainly fleeing crewmembers.

Eventually, the flaming ship ran around. In total, 86 passengers and 49 crewmen were killed. Victims’ bodies continued floating onto the New Jersey shore for some time.

The low-lying Meuse Valley in Belgium became the scene of tragedy when a strange “illness” struck residents on farms and villages within a 15-mile stretch from Huy to Liege. A perfect combination of factors came together in just the right way to create a modern era disaster—the first of its kind, but certainly not the last.

Meuse Valley was the site of many factories including chemical plants, zinc smelters, and coke ovens, all of which belched a constant stream of pollutants into the air. On December 1, residents noticed a strange, dense, cold fog had settled over the valley (due to temperature inversion). Visibility was poor, barely a few feet. Residents continued their business as usual, although the fog irritated their eyes and made it difficult to breathe.

By the second day, infants, and older and some middle-aged people showed signs of respiratory distress. Doctors couldn’t figure out the cause of the sudden “disease” manifesting in their patients—and then those patients began to die.

A total of 30 people died on December 3rd alone. The death toll rose. Suspecting the cause due to chemical fumes from the factories—which continued operating despite the emergency—many residents tried sealing themselves into their houses, stopping up chinks with paper or rags to keep out the fog. To prevent their valuable cattle dying, some farmers drove their cows inside the kitchen.

Although the term “smog” was coined by a British doctor in 1905 as a combination of smoke and fog, the phenomena was very little understood. Some residents believed the fog over the Meuse Valley had a supernatural origin. Others thought the deadly fumes came from caches of poison gas canisters secreted by the Germans during WWI. As news of the disaster was reported in newspapers worldwide, speculation ran rife.

By the time the fog lifted five days after it began, between 60-75 people were dead. Thousands were ill or suffered permanent injury. Two years later, Belgian authorities investigating the mystery officially reported that the fog had been trapped over the valley due to freak weather conditions, and that toxic gasses from the factories caused the deaths.

The 498-foot Greek steamship SS Heraklion, with Captain Vernikos at the helm, regularly worked a ferry route on the Aegean Sea from Crete to the Greek mainland until a night in December, when the weather, inexperienced officers and crew, and a rogue refrigerator truck combined to capsize the ship, killing many of the passengers and crew.

At the dock in Chania, Crete, the captain of the Heraklion waited for the arrival of a refrigerated trailer truck carrying oranges, which came late and threw the ship off schedule by two hours. It’s been speculated that the crew, flustered and rushed by the delay, improperly secured the truck in its position in front of the ferry’s loading doors. By that point, the crowded ship was heavily laden with cargo and passengers.

During the trip to Piraeus, Port of Athens, a severe gale began to blow with wind gusts up to 63 mph. After midnight, the storm reached a critical point. Deadly waves continued battering the ferry’s hull, causing it to pitch back and forth. In the hold, vehicles including the trailer truck, tore loose from their ties. Each roll the ship made sent the truck crashing over and over into the loading doors. At last, the doors gave way, allowing the sea to pour in.

The ship took a mere 20 minutes to sink. Untrained officers and crew who had no idea how to conduct an emergency evacuation panicked, as did the passengers struggling to find an exit from their cabins to the decks.

The exact number of victims is unknown since accurate records weren’t kept, but it’s estimated 268 passengers and crew perished, including the captain, who went down with the ship. The 46 survivors clung to life jackets and debris, trying to stay afloat in the dark, oily water while bizarrely, oranges bobbed in the waves around them. Video of a newsreel briefly showing search and rescue operations can be seen here.

The Heraklion’s owners, Typaldos Line, were charged with negligence.

When ominous rumblings and minor explosions came from the volcano Mt. Pelée on the French Caribbean island Martinique, citizens of St. Pierre, a waterfront town overlooked by the mountain, weren’t too concerned. Volcanoes meant lava, and lava flowed slowly, leaving plenty of time to get out of the way … right? Unfortunately, they were wrong.

Signs pointed to a disaster in the making, beginning with ash showers, tremors, and clouds of rotten egg stinking gas. Fleeing red ants, centipedes, and other insects invaded villages, as well as poisonous snakes which caused the deaths of at least 50 children and 200 domesticated animals and pets. Water in the Etang Sec crater boiled, overflowed into River Blanche, and the resulting flood killed 23 workmen at a rum distillery near St. Pierre.

Some people, unconcerned by the activity, even came to St. Pierre from nearby cities to view the spectacular sight—a very bad decision since on May 8th, just before 8 A.M., Mt. Pelée exploded in an eruption of superheated ash, rocks, and gas that flowed so quickly downhill, residents of St. Pierre had only a minute before the avalanche hit.

Warehoused barrels of rum exploded. Hundreds of fires burned. Ships in the harbor were destroyed. And 2,500+ people died almost instantly, most of them as a result of breathing in the searing air, heated to more than 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The majority of the bodies were badly charred, and the city was completely buried under volcanic ash.

Out of St. Pierre’s entire population, there were two known survivors.

In the midst of the Great War, one of the worst railway accidents in French history occurred, largely because of official impatience, arrogance, and incompetence, and in the aftermath, the government tried to cover it up.

As a consequence of wartime manpower, equipment, and supplies shortages, railways were understaffed and the lines considerably overloaded. In December 1917, an estimated 1,000 French troops who had been fighting in Italy waited in Turin for transportation across the Alps to Lyon, France. Two trains had been reserved for the Army’s use, but there was a problem: due to the lack of equipment and maintenance, only one locomotive was available.

Although officials were warned by experts that their preferred solution was too dangerous, they ignored advice and went their own way, hooking up the wooden carriages—19 in all—to the single locomotive and cramming the soldiers inside.

The driver knew the situation was set for disaster and at first refused to set out from the station in Turin. The locomotive might be able to pull the carriages, he argued, but in the mountains, the excess weight would put too great a strain on the brakes, creating an unsafe situation. However, an Army officer drew a pistol and threatened to shoot him if he didn’t comply. As France was at war, the officer had the right to make the demand and the threat, but later events showed he should have listened to the driver’s concerns.

The train set out on the main line to Lyon and after a little while, passed through the Mount Cern tunnel into France, close to the town of Modane, and began its descent. The driver’s worst fears were realized. Although he tried applying the brakes, the sheer weight of the carriages behind the locomotive hurtled the train faster and faster down the steep, four mile grade. Friction ignited the brakes on the carriages, setting them on fire. At the bottom, going at a speed of about 75 mph, the train derailed when the first carriage jumped the track.

Altogether, 800 people died. The wreckage burned so fiercely, almost half the bodies couldn’t be identified. Regardless of the horrific tragedy, since the Army was involved in making the decision that had led to so many deaths, the French government kept the accident a secret until more than a decade later, when the driver—who survived—spilled the beans.

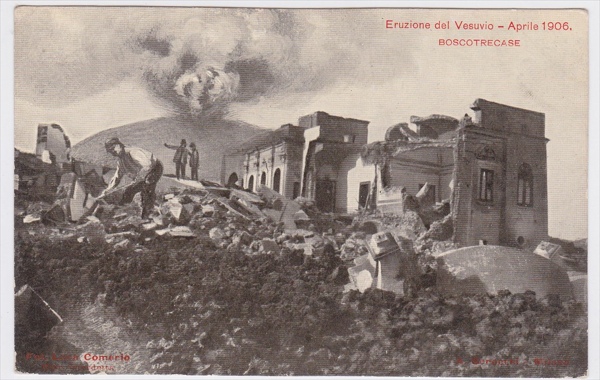

When it comes to the damage done by volcanoes, we think about deadly red hot lava, but there are other hazards that take lives just as easily. One of these dangers is ash, a lesson learned in Naples after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

In early April 1906, Vesuvius erupted violently, spewing tons of ash and debris for miles. An estimated 315,000 tons fell on Naples alone. On the morning of April 11th, due to an accumulation ash and cinders, the roof of the 600 square foot Monte Oliveto marketplace collapsed, trapping more than 200 people in the ruins.

Monte Oliveto was a very popular and busy market in the city, always full of stall holders and customers buying flowers, fruit, and vegetables. Trade was especially brisk in the mornings. Built with a sturdy iron framework and topped by a wooden roof, the building was designed to withstand every day weather—not the tons of ash thrown by Vesuvius that covered the city to a depth of three or more feet in some places.

Shortly after a religious procession passed through the street, the participants thanking God they were spared from worse during the eruption, the market’s roof caved in without warning. Those inside were buried alive. Rescue efforts began immediately, although hope seemed lost when the first bodies were taken out. Crowds of friends, relatives, and passers-by formed groups around the scene, praying, weeping, and pleading. Rescuers used their bare hands to clear away the debris. By the time the last victim was rescued from the rubble, the toll was high: at least 178 injured and 14 dead.

These weren’t the last victims of a collapsed building caused by the eruption of Vesuvius—when a church’s roof in San Giuseppe fell in due to the weight of the ash, an estimated 90 parishioners were injured and 105 killed.