Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

10 Unsettling Mysteries From Asylums And Institutions

Nothing good ever came from the history of lunatic wards and insane asylums. But sometimes, the events that occurred behind these closed doors are shrouded in so much mystery that we’ll probably never know the truth. With countless lives lost and so many names forgotten, there are at least a handful of stories that we know just enough about to stand out from the history books.

10 Willard Asylum’s Mystery Dead And Their Suitcases

The remains of the Willard State Psychiatric Hospital sit on the shores of Seneca Lake in New York. When the hospital officially closed in 1995, the workers who were shutting it down found scores of suitcases containing the belongings of people who had lived and died there, many of whom were long forgotten.

The contents of the suitcases tell stories like that of Mr. Frank, who was in Willard for three years before being transferred to the VA hospital in nearby Canandiagua. He died 30 years later after spending most of his life in an institution.

There was also Sister Marie, who was described in her patient files as ugly and whose religious visions and beliefs were classified as figments of her imagination. After her commitment to Willard, she was so traumatized that she adopted the personality of a nine-year-old girl. When Sister Marie died at 69 years old, her body was shipped off to be used in medical research.

Other suitcases shed less light on the lives of those who owned them. For example, the suitcase belonging to Ernest P. was empty.

For about 50 years, the patients at Willard were briefly remembered by at least one man, Lawrence Mocha, the asylum’s gravedigger. He lived at the cemetery and buried at least 1,500 people in rows of 60. Each grave was marked only by a number. In 1968, Mocha died at 90 years old and was also buried at the cemetery in a numbered grave.

Today, even those numbered markers are gone. New York State is blocking attempts at matching names with graves, stating that it would violate the privacy of those who died in the asylum and were buried by Lawrence Mocha.

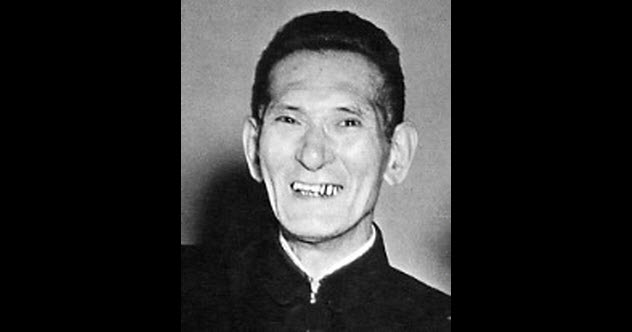

9 The Faces Of The Nazi’s Euthanasia Program Propaganda

There were several phases to the Nazis’ euthanasia program for the “life unworthy of life.” Overall, it’s estimated that about 200,000 people died from euthanasia, including the mentally disabled, the mentally ill, and the physically disabled.

In 1939, the Reich Ministry of the Interior made it law that midwives, nurses, and doctors report any developmentally challenged children to the government for assignment to special clinics where they were ultimately killed by starvation or an overdose of drugs. Originally, the program was for those under 17 years old, but by the time Hitler initiated the “T4” phase of the program, adults were included, too.

Gas chambers replaced the clinics. The categories of individuals in the program were defined to include people diagnosed with psychiatric and neurological disorders, the criminally insane, anyone who had lived in an institution for more than five years, and those not of German blood. The euthanasia programs were at the heart of the Nazis’ ethnic cleansing, and there was plenty of propaganda to promote the benefits to the public.

Life was painted as hopeless, endless torment for these undeserving people who couldn’t appreciate what they’d been given and were simply a burden on those around them. Films, slideshows, and photos were circulated to show the countless, nameless faces who became the embodiment of why the euthanasia program was the right thing to do. The photos showed doctors in asylums, patients lined up behind chain-link fences, and other people simply crowded together.

For the most part, we’re not sure who these individuals were or how they died. A few were described with the briefest of notations. One slide read, “Mentally ill Negro 16 years in an institution costing 35,000 reichsmarks,” making the cost of caring for these people another reason for the program.

Other pieces of propaganda give only slightly more information. There’s Emmi G., a 16-year-old diagnosed as schizophrenic, who was sterilized and then executed in 1942. A picture of an older woman had no name, just a notation that she had nonconformist beliefs. She died in January 1944.

A ledger dated April 1945 lists false causes of death for a handful of the hundreds of thousands of people whose remains were cremated and dumped into a communal pile. Sometimes, the remains were swept into urns and returned to families with falsified records.

8 Who’s Buried In The Numbered Graves Of Letchworth Village?

Letchworth Village was a New York asylum that opened in 1911. Until 1967, those who died there were buried in unmarked graves in a nearby cemetery in the woods. All but forgotten, these people have only rows of numbered steel markers to acknowledge their lost lives. A second cemetery was opened in 1967 that did mark the burial places of the newly dead.

After the residents of a nearby group home brought up the idea of remembering those who had lived in local asylums, a project was undertaken to match the names, numbers, and gravesites in the unmarked cemetery. But vandals and years of neglect had taken their toll, leaving many of the grave markers uprooted. Records remain of who was buried there, but it’s almost impossible to match the names with the numbers.

At the entrance to the cemetery, a bronze monument lists around 900 names but no numbers linking them to the plots in which the people were buried. For some, there’s not much of a name, either. They’re simply identified as “Baby Girl” or “Baby Boy” and perhaps a surname.

Like many other asylums, Letchworth Village was plagued with so many stories of abuse and mistreatment that it’s still believed to be home to some of the dead souls who suffered there in life. The eerie, impersonal markers—which will likely never be matched to those buried beneath them—seem only to add insult to injury.

7 Shumei Okawa

While confinement to an insane asylum might seem less than ideal for most of us, it may have allowed one of Japan’s most notorious war criminals to escape actual conviction for his crimes in the years following World War II.

On May 3, 1946, Shumei Okawa became the only civilian prosecuted in a military tribunal. On trial for his role in the Showa Restoration, he was accused of being a driving force behind the movement that assassinated Japan’s prime minister in 1932. The prosecution dubbed him an “international outlaw.” However, rather than trumpet the ideals of the Nazis, Okawa focused on touting Japan’s right to rule over the supposedly lesser people whom they had subjugated.

The trial was bizarre from the beginning. Okawa showed up in front of the tribunal dressed in a button-down shirt with bare feet, seeming to randomly sway and cry. At one point, he leaned forward and smacked the head of the person sitting in front of him, which was the last straw for the tribunal.

He was removed from the trial and passed to the care of Dr. David Jaffe, a US Army major and doctor who was asked to determine if Okawa was competent to stand trial. Jaffe diagnosed Okawa as having an advanced case of syphilis, so Okawa was sent to the Matsuzawa Hospital for the Insane.

Residing there for about 10 years, Okawa was eventually cured and released. He disappeared into relative obscurity, never convicted for his crimes. What’s still not known is whether he was truly ill or simply putting on a show to escape conviction and a prison term. In a book recently released by Jaffe’s grandson, he looks at the questions surrounding the diagnosis and admits that his grandfather only spent a few hours with Okawa before declaring him unfit to stand trial.

6 The Corpse Stain

Opening in 1874, the Athens Lunatic Asylum was one of Ohio’s largest facilities for dealing with the mentally ill. Locals called it “The Ridges,” and for years, it was the home of countless Civil War veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

As people began to drop off the teenagers they couldn’t control and the elderly they didn’t want, the facility became grossly overcrowded. The staff was overwhelmed, patients were gradually put to work on the property, and the quality of care spiraled downward. When the hospital closed in 1993, locals began to tell stories about the ghosts of abused residents who had died tragic deaths and were still haunting the hospital.

According to one story, a patient named Margaret Schilling disappeared on December 1, 1979. After a token effort to find her, the staff chalked her up as a loss. Her naked body was discovered 42 days later in a sealed-off ward on the top floor that had once been used to quarantine infectious patients. Officially, she died of heart failure, but what really happened is another story.

Before she died, Margaret removed her clothes, folded them, and placed them neatly beside her. By the time she was found, she had decayed so much that the substances leaking from her body left a stain on the concrete floor. Still there today, the stain is definitely in the shape of a human figure.

In 2008, the Journal of Forensic Sciences published a study that examined the stain. They found that it contained compounds that were consistent with a decomposing body. The biological agents and traces of cleaning agents are believed to have reacted to create the eternal stain.

So what really happened to Margaret? One version of the story says that she was a deaf-mute who had been hiding from the staff and was unable to call for help when she became trapped. Another version says that she suffered from severe disabilities and slowly froze to death in the cold winter. Either way, locals believe they still see her in the window on some nights, and it’s undeniable that there are parts of her that will remain in the asylum forever.

5 Foxborough State Hospital’s Lonely Burial

In 1893, Massachusetts opened the Hospital for Dipsomaniacs and Inebriates southwest of Boston. The institution, which would later become Foxborough State Hospital, started admitting those labeled as insane in 1905. A short time later, there was a massive shake-up amid reports of mismanagement and the abuse of patients. By the time Prohibition came, being a habitual drunk resulted in a prison term, not a stay at an institution. But the hospital survived anyway.

When the hospital finally closed in 1976, the property was divided and sold. More than 1,100 people were buried in the two cemeteries that belonged to the facility, but there was one isolated grave that wasn’t found until much later.

For years, the locals told stories about a person who had been buried alone, out in the woods, well away from the rest of the world. This person had supposedly died of something horribly infectious, and to keep the disease from spreading, the person’s remains were buried alone and unmarked.

While most thought the story was probably fiction, local historian Jack Authelet did some more digging—literally. He finally uncovered a small pile of stones, long forgotten, nestled between an abandoned building and some railroad tracks.

On October 2, 2010, Authelet organized a small memorial service for the unknown soul, marking the grave with a number in the same way that so many others were marked. No one will ever know the person’s name, the horrible nature of his or her death, and the reason that the person was buried in the middle of nowhere, still isolated even in death. But Authelet wanted to make sure that he or she was no longer completely forgotten.

4 Van Ingraham And The Fairview Developmental Center

In 2007, a patient in the state-run Fairview Developmental Center in California died under suspicious circumstances, sparking an investigation that has never been satisfactorily settled.

Diagnosed with severe autism as a child, Van Ingraham was committed to the center when he was eight years old. He lived there for 42 years. In 2007, his brother Larry Ingraham, a former police officer, received a voice mail saying that Van had fallen out of bed, breaking his neck and crushing his spinal column. The neurosurgeon who treated Van told his family that the injuries couldn’t have been caused by an accident, so Larry began digging deeper.

As he investigated, Larry realized that the occasional injuries he had seen on his brother—bruises and a black eye—were signs of abuse, not the acceptable hazards of living at the center as he had once believed. More than that, he uncovered hundreds of reports of patient abuse that had been filed against the center.

None of these cases were ever investigated further, so no one was arrested or held accountable. Most of the abuse victims were severely disabled, with some unable to speak and some diagnosed with single-digit IQs. Further research by a group called “California Watch” uncovered only two cases of alleged abuse between 2006 and 2012 that ended in an arrest.

Van wasn’t the only person who died under mysterious circumstances. A 25-year-old quadriplegic died from internal bleeding after coughing up swabs that were 10 centimeters (4 in) long. By the time protection agencies got around to examining the situation, there was nothing left to investigate.

Van’s family was awarded an $800,000 settlement, but they never received what they were really looking for—justice.

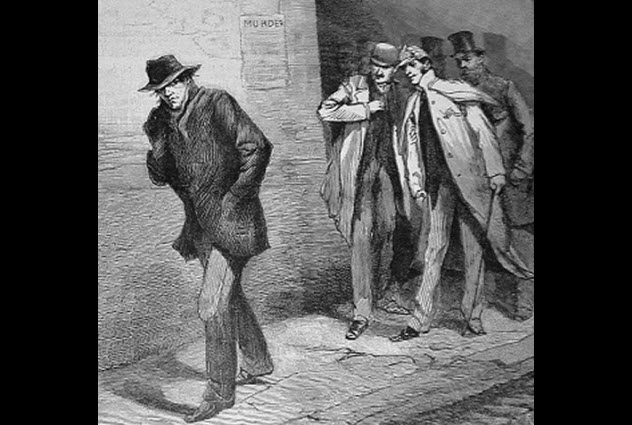

3 Thomas Hayne Cutbrush

For decades, people have speculated about the identity of Jack the Ripper. At the time of the murders, newspapers were convinced that one of the leading suspects was Thomas Hayne Cutbrush.

In 2011, authorities for the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum released a series of 26 documents that everyone hoped would shed some light on whether Cutbrush should still be considered a viable suspect. The documents didn’t do much to lessen the mystery, but they’re fascinating nonetheless.

Cutbrush’s downward spiral into insanity coincided with the start of the killings in 1888. At that time, he was working as a clerk. Even if the Ripper murders hadn’t occurred, his madness was extraordinary.

Cutbrush became absolutely convinced that his doctor was trying to poison him. Even though he appealed to one of London’s top lawyers for help, it wasn’t long before he was sure that the conspiracy to murder him extended to the law. After stabbing one girl on his midnight roam through the streets, Cutbrush was committed.

His trial ended in an insanity verdict, but numerous acts of violence were recorded after the ruling. At one point, he even tried to literally bite his mother’s face off when she came to visit him.

An 1894 edition of The Sun newspaper first suggested that Cutbrush might be the Ripper. One of the hiccups in the theory, which often states that the disappearance of the Ripper coincides with Cutbrush’s arrest, is a two-year gap between the last Ripper killing and the assault that got Cutbrush committed.

However, Cutbrush’s description matches that of the Ripper, including bright blue eyes and a limp. The newspaper article also claimed that there was proof that Cutbrush was the Ripper.

While it could be argued that the lull in violence makes it unlikely that he’s the Ripper, it doesn’t put him out of the running. There’s also an excellent reason why law enforcement might have wanted to hide anything they knew about him. Cutbrush’s uncle was a Scotland Yard superintendent who shot and killed himself around the time that the Ripper murders occurred.

2 The Mysterious Accuracy Of Starry Night

After Vincent van Gogh’s ear was mysteriously mutilated, he checked himself into the Saint-Paul de Mausolee Asylum in Saint-Remy-de-Provence. During 53 weeks of voluntary confinement, he churned out over 240 drawings and paintings, including his most famous work, Starry Night.

In 2006, when researchers from the Autonomous University of Mexico became curious about the swirls in that painting, they discovered something shocking. Somehow, van Gogh had recreated a scientific phenomenon that was still quite mysterious: turbulence.

Until the 1940s, most of the properties of turbulence were unknown. Then a Soviet physicist developed formulas and theories to explain how turbulence acted when smaller and larger eddies collided. Still one of the most complicated natural phenomena to understand, turbulence is almost impossible to see.

But somehow, van Gogh got his swirls absolutely right, down to the smallest mathematical details. We have no idea how he did it. Another complicated scientific principle is represented in an impressionist phenomenon called “luminance,” which happens when our brains see different colors in a painting like Starry Night as though they’re flickering.

The researchers examined more of van Gogh’s work and were stunned to find that he’d repeated the pattern in other paintings. This raises the as yet unanswerable question: Does the turbulence in nature mimic the turbulence of mental illness?

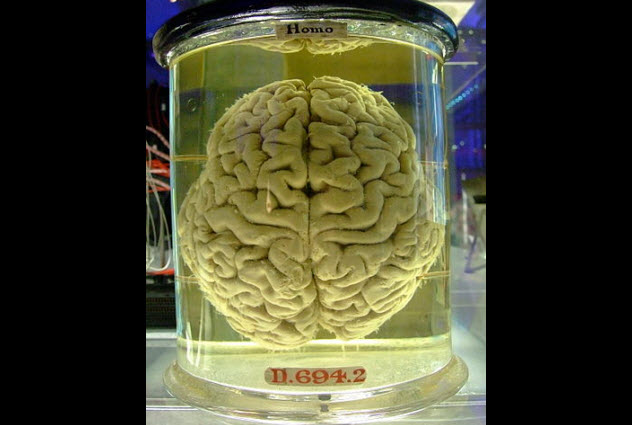

1 Charles Whitman’s Brain

In the 1950s, the Austin State Hospital (formerly the Texas State Lunatic Asylum) began collecting the brains of its deceased patients to determine if mental illness had a physical component. These brains were preserved in jars that were carefully labeled with the patients’ names and diagnoses, with around 200 specimens canned and shelved over approximately 30 years.

In 1986, storage space was becoming a problem. The hospital offered to give the brains to anyone who wanted to use them as a research tool. With major universities vying to get them, the collection was eventually transferred to the University of Texas in 1987.

Among the brains was that of Charles Whitman, the infamous ex-Marine who climbed a tower at the University of Texas in 1966 and started shooting. By the time he was shot dead by police, Whitman had already killed 16 people and wounded 32 more. Earlier, he had killed his wife and mother. Whitman left a note requesting that someone look at his brain to find a reason for all the thoughts he’d been having. Later, it was discovered that he had a brain tumor.

In the mid-1990s, researchers took a look at the university’s collection of brains, which had only been gathering dust until that time. When they searched for Whitman’s brain, they couldn’t find it. Along with about 100 other brains, it had disappeared.

Various people at the university came up with different excuses to explain the missing brains. The possibilities included that the brains had been moved, thrown away, placed in storage elsewhere, or returned to the state asylum. The state said they never got the brains back.

According to a December 2014 update, between 40 and 60 of the brains were destroyed by the university because they had degraded to the point of being unusable for research. However, the university said that Whitman’s brain was not among them, now claiming that they had never received his brain in the first place.