Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

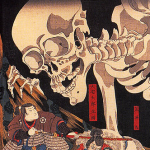

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

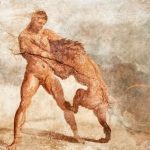

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

10 Shocking Myths of Modern Psychiatry

Since the late 19th century, psychiatry in the Western world has claimed to be a medical specialty. By stressing that mental disorders are an “illness like any other,” psychiatrists strive to keep the same status as their colleagues in cardiology, oncology, and other specialties. Mental disorders, they argue, should be viewed no differently from diseases like heart failure or leukemia.

There is a dearth of evidence for this grand claim. Psychiatry, ably abetted by the drug industry, has created an idea of mental health that may bear little resemblance to reality. Listed below, in no particular order, are the 10 biggest myths of modern psychiatry.

10Mental Illness Is The Result Of A Broken Brain

Most psychiatrists believe that the main cause of mental illness is a life-long brain defect. We are often told that people diagnosed with schizophrenia (a severe mental health problem involving hearing voices, jumbled thoughts, and unusual beliefs) display brain deformities. Using the latest technologies, we are shown not-so-pretty pictures of schizophrenic brains displaying abnormal bumps and craters.

But recent research suggests that the antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia can cause human brain defects directly in proportion to the amount of medication ingested—the more of the drug consumed, the greater the extent of damage to the brain. Despite failing to find any strong association between brain shrinkage and the intensity of the schizophrenia, the researchers cling to the idea that antipsychotic medication only aggravates underlying brain defects. However it has also been demonstrated that antipsychotic drugs given to macaque monkeys reduce their brain volumes by around 20 percent, casting further doubt on the broken brain dogma.

Furthermore, childhood abuse (a major risk factor for schizophrenia and other disorders) is known to alter brain structure, suggesting that early trauma may contribute to structural changes in the brains of adults with mental health problems.

Thus, it seems possible to conclude that brain defects in schizophrenia sufferers are likely to result from what life in general, and psychiatry in particular, inflict upon them.

9Severe Mental Disorders Are Mainly Genetic In Origin

Most psychiatrists also link the risk of schizophrenia to the genes we inherit from our parents. In support of this argument they point to studies of identical twins (who share exactly the same genes), which seem to show that if one twin has schizophrenia there is a very high chance the other will too. Almost 70 years ago, one of the most famous twin researchers, Franz Kallman, announced an 86 percent concordance rate for schizophrenic twins—in other words, if one twin was diagnosed with schizophrenia there was an 86 percent chance their sibling would suffer from the same condition—suggesting a huge genetic influence.

Although these claims have moderated over the last few decades, 21st century psychiatry persists in the view that schizophrenia is primarily genetic in origin. As well as twin studies, psychiatrists cite adoption research that measures the concordance rate between blood relatives separated early in life. The idea is that this rules out the possibility that aspects of a shared environment may account for the correspondence. By demonstrating that children of schizophrenic mothers continued to be at greater risk of developing schizophrenia themselves, despite being adopted away as babies, the adoption studies are often considered to be the most convincing evidence of a genetic basis for the condition.

However, decades of research has signally failed to identify the genetic marker that supposedly underlies schizophrenia. Meanwhile, psychiatrists like Jay Joseph have sought to demonstrate that the twin and adoption studies touted as proof of a genetic cause are riddled with biases, ranging from blatant misreporting of the data to subtle statistical tricks. Reviews of the research that have excluded the effects of these flaws and focused only on more recent, better designed studies, have estimated the schizophrenia concordance rate for identical twins and non-identical twins to be 22 percent and 5 percent respectively, indicative of a real but modest genetic contribution—on a par with the genetic contribution to traits such as intelligence.

Life experiences seem to be a much more potent cause of the symptoms labelled as schizophrenia. For example, childhood sexual abuse has been convincingly shown to render a person 15 times more susceptible to psychosis in adulthood. The size of this effect is far in excess of any gene yet discovered.

8Psychiatric Diagnoses Are Meaningful

Medical experts diagnose illness—the symptoms presented guide them to deduce the presence of a named disease process that explains the cause and maintenance of the patient’s complaints. So if a doctor makes a diagnosis of diabetes, we know that we lack a hormone called insulin and that injections of it should improve our health.

But if mental health problems are not primarily the result of biological defects (or a “broken brain”), psychiatry is faced with a problem that is impossible to solve. So how do psychiatrists overcome this fundamental obstacle? They gather around a table and invent a list of mental illnesses!

In the USA, this list is crafted by the American Psychiatric Association and is grandly titled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM for short). The latest edition (DSM-5) of this psychiatric bible thrust itself onto the world last year and lists over 300 mental illnesses.

A useful diagnosis should pinpoint a specific underlying pathology that can explain the symptoms, provide guidance as to the appropriate treatment, and display high levels of reliability (so that two or more psychiatrists assessing the same person will typically reach the same conclusion). DSM-5 (along with its predecessors) fails on all three fronts. Even a key figure in earlier editions of the DSM berated the latest offering as “deeply flawed” for mislabeling normal emotions as mental illness.

7The Number Of Mentally Ill People Is Increasing

Psychiatry constantly tells us about the vast number of “mentally ill” people there are in the general population, most of them never having received professional help and many not even aware that they have a problem. One recent study claimed that almost half of all Americans will suffer a formal mental illness at some point in their lives.

The central reason for this apparently ever-increasing number is that psychiatry keeps widening the net of mental illnesses to incorporate more and more normal reactions to life’s challenges. According to DSM-5, if you remain sad two weeks after the death of a loved one you are suffering from “major depressive disorder.” A child displaying tantrums risks acquiring the label of “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.” And a modest degree of forgetfulness in later years means you are suffering with “mild neuro-cognitive disorder.” It is a wonder anyone manages to avoid the grasp of these ever-elongating psychiatric tentacles.

6Long-Term Use Of Antipsychotics Is Relatively Benign

Psychiatry carries a shameful history of failing to recognize when its treatments are doing more harm than good. Whether it be mutilating genitals, slicing brains (“leucotomy”), surgically removing organs, inducing comas with potentially lethal doses of insulin (“insulin coma therapy”) or triggering fits by electrocuting people’s heads (“electro-convulsive therapy”), psychiatrists always seem the last to realize they are damaging the very people they are paid to help.

And antipsychotic medication could well be a similar story. Long term use, particularly of the older (typical) antipsychotics, blights around 30 percent of patients with uncontrollable twitching and spasms of the tongue, lips, face, hands, and feet, an often permanent affliction known as tardive dyskinesia. The newer (atypical) antipsychotics are a little more forgiving in this respect, although not to the point of eliminating the problem altogether.

In addition to the curse of tardive dyskinesia, long term antipsychotic users may also be at greater risk of drug-induced heart disease, diabetes, and obesity (the newer atypical type being arguably more problematic in this regard). As we’ve already discussed, and perhaps most disturbingly of all, there is mounting evidence that antipsychotics may directly cause brain shrinkage.

5Effective Treatment Of Mental Illness Is Essential For Public Safety

High-profile psychiatrists continue to promote the myth of public safety being compromised by psycho-killers in our midst. A striking recent example is provided by Jeffrey Lieberman, the president of the American Psychiatric Association, who claimed that, “shocking acts of mass violence are disproportionately caused by people with mental illness who have not gotten treatment.”

Although there may be rare instances where a person’s psychotically-driven paranoia leads to an act of violence, a recent Dutch study calculated that only a tiny 0.07 percent of all crimes were directly attributable to mental health problems. A UK study found that only 5 percent of all homicides are carried out by people who have acquired a diagnosis of schizophrenia at some point in their lives, a figure dwarfed by alcohol and drug misuse, which contribute to over 60 percent of such cases.

To put the risk posed by insane people into perspective, it has been estimated that the odds of us being murdered by a psychotic stranger are about one in 10 million, on par with being hit by lightning. And people suffering mental disorders are much more likely to be the victims of crime than the perpetrators—one study found that those diagnosed with schizophrenia were 14 times more likely to be the subject of a violent crime than to commit one.

4Many People With Mental Health Problems Have No Potential To Recover

Anyone who has spent time within Western psychiatric services could be forgiven for assuming that many of those afflicted with mental health problems were hopeless cases with little or no chance of improvement. Such pessimism is unsurprising, given that many psychiatrists believe that mental illness is caused by brain defects, and is a life-long condition akin to diabetes or heart disease.

The language of psychiatry screams hopelessness, as illustrated by the oft-used terms “severe and enduring mental illness” and “chronic schizophrenia.” Yet the reality is very different. Even when medical views of schizophrenia are considered, along with narrow, symptom-reduction definitions of recovery, the expectation is that around 80 percent of sufferers will, in time, achieve some significant improvement.

Recovery from mental health problems doesn’t necessarily equate with the elimination of all symptoms. A more meaningful definition for many sufferers might involve the pursuit of valued life goals, and the subsequent achievement of a worthwhile life, irrespective of difficulties. In this sense, to move towards recovery requires the transition from pathology, illness, and symptoms to a greater focus on health, strengths, and wellness. Free from the shackles (and self-fulfilling pessimism) of psychiatric dogma, meaningful recovery is a realistic goal for all.

3Psychiatric Medications Are Very Effective

In the USA alone, 3.1 million people were prescribed antipsychotics in 2011, at a total cost of $18.2 billion. These drugs continue to be the core treatment for people suffering with schizophrenia and practice guidelines from around the world recommend them as a first-line intervention.

In the same year, a staggering 18.5 million Americans (about 1 in 14 of the youth and adult population) were swallowing antidepressant drugs. The current view of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the United Kingdom is that three months of treatment with antidepressants will “much improve” 50 to 60 percent of patients.

But the effectiveness of both antipsychotics and antidepressants has been seriously challenged.

Surprisingly few studies have directly compared antipsychotics with a sedative drug like diazepam (Valium) for someone suffering an acute psychotic episode. A review of the research that has been carried out demonstrated that general sedation can have a significant effect on psychotic symptoms. This suggests that reduced arousal could be the common factor in achieving respite, as opposed to the specific “anti-psychotic” effect touted by drug manufacturers.

A recent review of 38 clinical trials of atypical antipsychotics (the newer type most commonly prescribed) concluded that they achieved only moderate benefits when compared to a placebo and “there is much room for more efficacious compounds.” The authors also found evidence of a publication bias—in other words, researchers (many sponsored by drug companies) may have been guilty of selectively publishing those studies showing the drug in a good light, while withholding those where the results were disappointing.

Furthermore, it has been established that around 40 percent of people who suffer psychotic episodes can improve without any medication at all, thereby casting further doubt on the appropriateness of blanket antipsychotic perscription.

As for antidepressants, the case is more complicated, but a recent scholarly review concluded that, overall, benefits from antidepressant use did not meaningfully exceed those from a placebo. Although the authors reported that a small number of the most severely depressed patients achieved a level of drug-placebo difference that did reach clinical significance, this probably reflected a decreased responsiveness to placebo rather than an increased responsiveness to the antidepressants.

However, a subsequent group of researchers who re-examined the results concluded that 75 percent of patients on antidepressants did show some improvement, but that the other 25 percent actually suffered a deterioration in their depressive symptoms. This risk of worsening symptoms led the original study’s author to conclude that “antidepressants should be kept as a last resort, and if a person does not respond to the treatment within a few weeks, it should be discontinued” in favor of physical exercise and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, which have both been shown to have a positive effect on depression sufferers.

2An “Illness Like Any Other” Approach Reduces Stigma

Psychiatrists often lament the everyday stigma and discrimination faced by people with mental health problems and emphasize the importance of educating the general public about these disorders. Under the banner of mental health literacy they strive to convince the public that schizophrenia and depression are illnesses like any other, primarily caused by biological defects such as biochemical imbalances and genetic brain diseases. Many psychiatrists believe that promoting biological causes for mental health problems will result in the perception that the afflicted are not to blame for their mental disorders, thereby improving attitudes towards them.

On the contrary, trying to convince the general population that schizophrenia and depression are diseases like diabetes is likely to exacerbate negative attitudes towards people with mental health problems. A recent literature review found that in 11 out of the 12 studies examined, biological explanations of mental disorders led to more negative attitudes toward sufferers than explanations based on a person’s life experiences. In particular, “illness like any other” explanations encouraged social exclusion and inflated perceptions of dangerousness.

1Psychiatry Has Made Huge Progress Over The Last 100 Years

Many medical specialties can boast impressive progress over the last 100 years or so. Vaccines for polio and meningitis have saved millions of lives. The discovery of penicillin, the first antibiotic, revolutionized our fight against infection. Survival rates for cancer and heart attacks are steadily improving. But what has society gained from more than a century of professional psychiatry? Apparently surprisingly little.

Psychiatry’s claims of progress have been commonplace. Edward Shorter, in the preface to his book, A History of Psychiatry, swanks that: “If there is one central intellectual reality at the end of the twentieth century, it is that the biological approach to psychiatry—treating mental illness as a genetically influenced disorder of brain biochemistry—has been a smashing success.” Recent, high-profile commentators continue to stubbornly defend psychiatry’s status as a bone fide medical specialty.

But the cold facts paint a radically different picture. If you are ever unfortunate enough to suffer a psychotic episode, you will have a greater chance of recovery if you live in the developing world (Nigeria, for example) than you would in the developed world (e.g. the USA). The overuse of psychiatric medication in Western countries seems to be the primary reason for this difference.

Furthermore, you have no more chance of a recovery from schizophrenia today than you would have had over a century ago. A recent scholarly review of 50 research studies concluded that: “Despite major changes in treatment options in recent decades, the proportion of recovered cases has not increased.”

Psychiatry a smashing success? I don’t think so!

I am a freelance writer who recently opted for early retirement following 33 years of continuous employment in the UK’s psychiatric services, mostly as a clinical psychologist. During my career as a mental health professional, I have written around a dozen papers, published in academic journals or as book chapters. Since retirement, my writing focus is shared between criticisms of western psychiatry and humor.

More of my mental health writing can be found on gsidley.hubpages.com/ or at twitter.com/GarySidley.

For humor articles and chit-chat, visit brianjonesdiary-menopausalman.blogspot.co.uk/, facebook.com/gary.sidley, and bubblews.com/account/108867-gsidley.