Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Ambitious Plans For Creating Utopian Communities In America

Throughout the relatively short history of the US, there have been some pretty epic, ambitious, and sometimes downright bizarre attempts to create utopian communities within the country’s borders. For some, the ideas that the Founding Fathers had just weren’t good enough, and they wanted something even better.

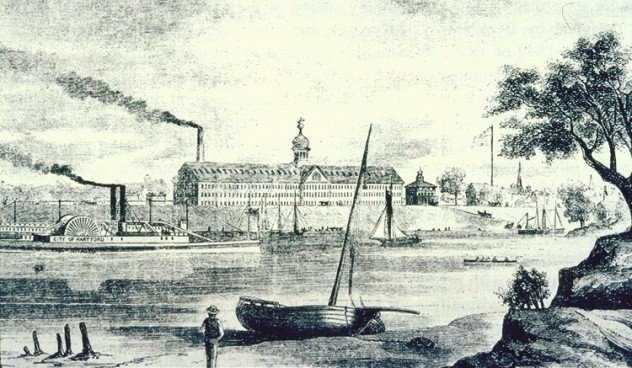

10Coltsville, Connecticut

Samuel Colt is credited with changing gun manufacturing forever. He created the Colt pistol, the “gun that won the West,” and he did a lot of it at Colt’s Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company just outside of Hartford, Connecticut. It was there that he not only revolutionized manufacturing processes, built a new branch of the railway, and built a dyke to protect what had previously been an all-but-unusable floodplain, but he also tried to create a utopian village for all of his workers.

The village only exists in pieces today, including about 10 of the original 50 brick buildings that Colt built as six-family homes. Those are now low-income housing buildings, but Colt went even farther than that. He wanted to encourage immigrants to come to the US specifically to work in his factory, so he constructed the weird blue dome inspired by Russian architecture that still stands today. And it still looks as out of place as it ever did. There’s also a row of Swiss-inspired chalets, and at one time, the entire area had been built up into an entire utopian community for his workers, all with the goal of making them feel at home in their new country. There were parks and botanical gardens, greenhouses, and even a German beer hall.

Colt built dance halls and social clubs, and he especially encouraged the development of a new craze that the kids seemed to like: the bicycle. He built churches and a concert hall, and he established the community’s own brass band. Even the look of the factory was designed to harken back to European architecture, and even though he made it perfectly clear that he expected his employees to work hard while they were on the clock, he also made a one-hour lunch break mandatory.

Colt ultimately died of gout at the age of only 47, but the community that he had created for his workers continued to thrive under the guidance of his wife. Tragedy continued to cloud her life, though, and with three children dying young and their fourth dying in a boating accident, there was no one left to continue the community. Many of the buildings still stand, with the Colts’ home, Armsmear, willed away to become a retirement home for widows.

Now, there are plans to further preserve the community and Colt factory with the establishment of the Coltsville National Park.

9Fruitlands Commune, Massachusetts

The Fruitlands Commune was established in June 1843, and by the new year, utopia was closed. Over the course of a handful of months, there were only truly about 14 people involved, and the man at the head of it all was Bronson Alcott. With him was his 10-year-old daughter: future writer Louisa May Alcott.

The goal was a straightforward one that ended up being not at all as simple as it sounded. Alcott wanted to return life to what it was like in the Garden of Eden, and that meant some pretty strict rules. The only food allowed was what they could grow on trees or vines because Alcott said that he didn’t want to consume anything animal-based or anything that would mean a sacrifice of “life force.”

This whole thing was made even more complicated by the fact that none of the members of the commune actually had any farming experience, and they didn’t have any actual fruit trees on their property. And, because they couldn’t use anything that was taken from an animal, that also put a limit on the use of oil lamps, which in turn impacted heating and lighting. Alcott even went as far as to forbid the growing of root vegetables because he said the worms would be disturbed. Wool and wax were also forbidden, along with the use of any kind of fertilizer. Given the climate of Massachusetts, it resulted not only in long periods of extreme discomfort, but chronic illness and, in turn, constant fighting.

Alcott’s attempts at luring new people to his community were an absolute failure, and his daughter’s diary is a pretty heartbreaking account of the fighting that went on between Alcott, his wife, and their other leaders.

The effort even got the attention of some of the country’s literary greats. Emerson and Thoreau both wrote about the endeavor. Specifically, though, they wrote about how it was going to fail. It wasn’t helped along by the fact that those who did try the experimental commune were a little bit more extreme than just eccentric. Their residents included a nudist who believed that clothes were a hindrance to the soul and a man who was so dedicated to his beard that “Persecuted for Wearing The Beard” was engraved on his tombstone.

8Harmony and Economy, Pennsylvania & New Harmony, Indiana

The Harmony Society had its roots in Germany in the 1780s, but founder Johann George Rapp wanted more freedom for their Anabaptist sect. At the time, Germany was strictly Lutheran, so he and his adopted son picked up and moved to the United States.

The Rapps moved to Pennsylvania in 1803, and by 1805, The Harmony Society was official. And they thrived. By 1814, they had grown to 7,000 acres of farmland and Harmony was a blossoming town with 130 homes. Selling this property, they moved on to establish New Harmony, Indiana. Their new home was on 25,000 acres, and when they outgrew that, they headed back to Pennsylvania and founded Economy.

Not only were their settlements home to massive agricultural complexes, factories, and manufacturing industries, but by the middle of the 1800s, their per capita income averaged about 10 times the American average. They even built the largest communal hall in the US: the Feast-Hall. So what happened? The world didn’t end.

Rapp was preparing his community for the end of the world and the return of Christ, which he believed was going to happen any day now. All of their wealth was being amassed in preparation for the end times, and at one point, Rapp had more than half a million dollars worth of gold stored in his home. They saw America as being the place where they could not only practice religious freedom, but where they would find true happiness. They were also free to practice alchemy, and Rapp, who was 70 at the time, was free to take on a young woman as his assistant. The gossip that was spread because of their relationship, and of her subsequent marriage to someone else, started a fracturing within the belief system of the society.

In 1829, the Harmonists received a letter that supposedly heralded the arrival of the “Lion of Judah.” Supposedly seeing the city as a safe haven against the evil that was going to be ending the world any time now, Dr. Johann Georg Goentgen arrived with his “Lion,” who also happened to claim that he was the Messiah. The Rapps, who were rightfully suspicious that the man was not, in fact, the Messiah, tried billing him for his stay in the community. The Harmonists were split over whether or not the man was the Messiah. (He not only wasn’t, but he had tried his schtick before, in Europe, with no success in getting anyone to abdicate any throne to him.) They eventually ran the pretend Messiah out of town, but it was the next big personality, a man named John Duss, who ultimately ran the community into the ground.

7The Oneida Colony And The Bible Communists, New York

You can still visit the Oneida Community Mansion House today, located in upstate New York. The 8,600-square-meter (93,000 ft2) home was the home of a group of about 250 members all living together in what they called Biblical Communism.

The whole thing was the idea of John Humphrey Noyes. Born in 1811, he spent some time in the seminary before realizing that the church had it all kinds of backward. He believed that we weren’t supposed to be repenting and concentrating on not sinning, but instead, we were supposed to be searching for our own bit of personal perfection. It gave rise to his doctrine of Perfectionism, and he also believed that the Second Coming had already happened back when Christ’s immediate disciples were still around. What was left was for mankind to achieve a harmonious sort of perfect life on Earth.

Part of their belief system was to reject the conventional ideas of marriage as selfish. Instead, they focused on what they called Complex Marriage, where bonds of love and sex should be free to exist and develop between any and all couples and people. Exclusiveness was selfish.

All material property was shared by the community, and children were raised communally after their first year as well. In order to grow their order, they wanted to breed new generations rather than recruit new members, and with a practice called “Stirpiculture,” men and women deemed to be most appropriate to bear children together were requested to do so. Between 1869 and 1878, 58 children were born into the program.

After some trial and error, the community settled on the most profitable methods to sustain themselves: making fruit preserves, silk thread, and steel traps. Over the next few decades, though, the organization had one of the strangest fates of all utopian societies: They reorganized into a company which still exists today.

6George Pullman’s Capitalist Utopia, Illinois

Railroad tycoon and industrialist George Pullman meant well, sort of. The idea was that the town that he would give his name to would be a capitalist utopia, where his workers would live and be happy. And, in turn, they would be more productive and produce a better product. Pullman wasn’t just going to be the name of the town. He was going to own absolutely everything, and it was going to be built in the 1880s just outside of Chicago.

He planned for the town to house 12,000 people, and in three years, he spent about $6 million building his dream town. (That’s about $156 million today.) Everything was state of the art, from the infrastructure to the design of parks and trees. It had to be the best for his idea to work, after all, and it wasn’t the selfless attempt at making the world a better, more comfortable place that Samuel Colt had (perhaps ironically) tried to create.

Pullman believed that the working class masses were little more than cavemen who had learned how to control their thumbs. He believed that if he created a town that was beautiful enough and filled with enough fine things and culture, that he could elevate the working class into something better than what they were. If it sounds like the stuff of a dictatorship, it absolutely was. Pullman’s plan for his workforce also meant that no one was allowed to deviate from his grand vision right down to the assignment of certain types of people to certain homes within the community. Managers had the best homes, for example, and workers couldn’t actually own their homes. They had to pay rent. That was, of course, only if you were white. Otherwise, you weren’t even allowed to live in town.

And, if you didn’t live in town, Pullman took it personally. Sure, you could get a job with him, but he knew you weren’t a member of his community, and he made it clear that your job wasn’t all that safe.

Pullman also forbade his workers from drinking alcohol, but he did build a hotel in town to serve it to guests. He owned the one shopping center in town where everything was sold at incredibly high prices, and public gatherings were also forbidden. And there were also spies in town, there only to keep an eye on everyone and make sure Pullman’s laws were obeyed.

The whole thing came to a crashing halt with an economical downturn in 1893. People tolerated it because they had little choice, but when Pullman started cutting wages and kept the rents and pricing the same, the Pullman employees revolted.

Those that didn’t live in Pullman joined a labor union, which was also against the law in Pullman. Eventually, the US president called in the military to put down the action, which was more of a riot than a strike. Clearly, Pullman was only a utopia for the man who named it.

5New Llano, Louisiana

Socialism wasn’t always a bad word in the US, and well into the 20th century, there were attempts at creating a socialist utopia within the confines of the nation. In 1917, one such community, called Llano del Rio, had already been successfully established in California. The problem was one of a water shortage, though, and forced to relocate, the colonists packed up and moved to Louisiana.

The colonists weren’t just a community; they were a corporation. They bought the Gulf Land & Lumber Company and, even though some of the neighboring communities weren’t too sure about these socialists, the idea of a communal lifestyle and sharing of resources became a popular one in the difficult environment. New Llano started advertising for new members, but internal problems led to internal fighting, and it wasn’t long before the Great Depression hit.

Suddenly, socialism didn’t seem so bad. New Llano was flooded with people wanting in, but many of the new members weren’t capable of pulling their own weight. The strain of the depression, coupled with the desperation of the flood of new members, meant that the colony needed to keep looking for new ways to support itself.

Ultimately, it couldn’t. At the time their corporate community folded in 1939, their businesses, homes, factories, and their 20,000 acres would be sold for a pittance.

4Nashoba, Tennessee

Nashoba was a strange experiment in an anti-slavery utopia that wasn’t just a community, but a chance for freedom. Established in the 1820s by Frances Wright, Nashoba was meant to be a community where slaves and former slaves would live, work, and be educated with the ultimate goal of not only freedom and self-sufficiency, but of ultimately leaving the US.

Wright, born in Scotland, educated in London, and well-traveled, was good friends with the Marquis de Lafayette. Their friendship afforded her the opportunity to travel in circles that included men like Thomas Jefferson, but when she saw the consequences of slavery, she wanted to do something to help free those that were born into bondage. With help from Lafayette and Andrew Jackson, she purchased 2,000 acres and set up Nashoba.

Wright also purchased the freedom of 15 slaves and settled them on her new property. Her goal was to form a community in which they would not only work, but also learn. The community, she thought, was destined to be a multiracial one that would prepare former slaves for their independence.

It absolutely didn’t work, though. Conditions were incredibly harsh, and Wright was ill-prepared for her role as overseer and teacher. By 1827, she had gone back to Europe to try to raise more money to support the community, and by the time she made it back to Nashoba, there were only a handful of people left. Discouraged, she headed up to spend some time in New Harmony, Indiana. By 1829, she went back to Nashoba to find 39 people struggling to make ends meet.

Faced with the failure of her social experiment but unwilling to abandon the people who were living there, she made arrangements for everyone to move to Haiti. They did, and they were welcomed by the country’s president.

3Home Of Truth, Utah

In 1933, Marie Ogden settled her fledgling community in Dry Valley, Utah. A long-time devotee of the spiritual and the occult, Ogden was at the head of the School of Truth and a utopian community that she claimed was going to be nothing less than God’s Kingdom on Earth.

She required that her followers do some of the pretty usual stuff, like giving up their earthly possessions and becoming at least mostly vegetarian.

They also had to believe in her magic typewriter which Ogden claimed would come to life and type out messages from God. It was her typewriter that told her Dry Valley was the center of everything, and that it was there that she would find the Home of Truth.

They settled not far from the Mormons, who originally paid them little attention. But Ogden was also determined to grow her community, and when she purchased the local newspaper, the San Juan Record, she also started publishing articles on their beliefs and the messages she was receiving. In 1935, they published an article called “Rebirth of a Soul,” in which they talked about the death of one of their members, Edith Peshak.

She wasn’t really, truly dead, though, she was just resting. Ogden was insistent that she was in a state of purification, and when local authorities investigated, they found that the commune was in possession of Peshak’s body. However, it was preserved in a way similar to mummification and, since it presented no health risks, they couldn’t do much about it.

Two years passed, and gradually, when Peshak didn’t return to life, Ogden’s followers began to trickle away. Eventually, one of her former members confessed that he had been a part of the group that had constructed a funeral pyre for the dead woman, and after that, the commune fell apart.

2Octagon City, Kansas

Octagon City was supposed to be a utopian community based around exactly that: the octagon. Started in 1856 by Henry Clubb, the idea was originally going to encompass a handful of views that he had very strong feelings on. It was going to be a vegetarian society, and with the help of the octagon buildings, it was going to be super-healthy.

The ideas about the octagons weren’t his. In 1848, noted phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler published a book called The Octagon House: A Home For All, or A New, Cheap, Convenient, and Superior Mode of Building. A house shaped like an octagon wasn’t just a house that optimized space, but it was also a house that meant more natural sunlight and better air circulation. Hence, better health.

When Henry Clubb decided to use the idea as the basis of his new, healthy-living city, it was a dismal failure. Most of the people who were willing to give it a chance left only after a few months, mostly because they had been promised that they were moving into a busy, blossoming city. In reality, it was tents and a log cabin. Even though the most basic and important part of his community was that it was going to be vegetarian, he failed so completely at recruiting vegetarians that he eventually opened it up to everyone in an attempt to save the idea.

He was convinced, though, that the combination of the octagons and being vegetarian was the thing. Not eating meat, he said, would be likely to make you immune to disease, it would allow you to live longer, and it would allow you to live better. He attempted to appeal to the more intelligent people, who wanted to reap the benefits of a vegetarian diet, to come and join his commune.

As impressive as his sales pitch might have been, when New Yorker Miriam Colt wrote about her experience there, it involved words more along the lines of “dreary” and “sinister” instead of “utopia.” Needless to say, those people that he did succeed in recruiting mostly kept on moving.

There’s nothing left of the settlement today. Until 2007, a historian had attempted to keep up a small memorial to the failed commune, but finally gave up when vandals showed no signs of giving in.

1The Society Of The Woman In The Wilderness, Pennsylvania

Many people who left Europe for the US did so because they were searching for religious freedom. In the 1690s, Johann Zimmerman, a one-time Lutheran minister and Heidelberg University professor, gathered a group of people who had the same desire he did: They wanted to make their religious choices for themselves. As that absolutely wasn’t going to happen in Germany, they decided to head to Pennsylvania, where William Penn had begun his “Holy Experiment,” to create a community of religious tolerance and freedom.

Zimmerman and his followers believed that religious freedom wasn’t just important, but it was important right then. He’d read the signs, and he believed that the Second Coming was going to be in 1694. Not only that, but Pennsylvania was right in line with all the signs, too. He believed 40 was an important number, and Philadelphia was on the 40th parallel.

He died before the group could leave on their trip, but Johannes Kelpius quickly took the reins. The group made it to America and founded their society in the Pennsylvania wilderness. They devoted themselves not only to to religion, but to celibacy, alchemy, astrology, and prayer. Calling themselves the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, the goal was to create a perfect community where they were free to practice their numerology and their alchemy. They also wanted a place to set up their telescope and watch for Christ to return. Needless to say, he never did.

The original group began to fracture, with members and monks wandering off when the Second Coming didn’t, well, come. Kelpius died in 1708, succumbing to tuberculosis, and the order continued on for another 40 years. Even though they kept their isolated ways, they made it a point to help anyone who sought them out, offering everything from medical knowledge to carpentry skills. Far from forgotten, in 1961, the Rosicrucians claimed their society as the first in the New World, naming Kelpius as America’s first Rosicrucian Master.