Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Facts of the Murder Trial That Launched the True Crime Trend

Today, Americans follow true crime with morbid fascination. Tragic murder cases from O.J. Simpson and Casey Anthony to Gabby Petito and the Delphi Murders are obsessively hounded over by media members and true crime fans alike. That all had to start somewhere—and it long predates O.J.’s courtroom spectacle.

In fact, America’s first true crime fascination came about with the 1836 murder of a woman named Helen Jewett. Jewett was a sex worker in New York City. In April of that year, she was found dead in her bed with three head wounds. The bed had also been set on fire. Her client for the night was a man named Richard Robinson. Immediately, he became the prime suspect.

The ensuing fervor swept across the nation. Jewett was known for her intelligence and wit. Plus, her seemingly innocent beauty captivated the American public. Meanwhile, Robinson was a wealthy young man from a well-to-do family. The duo had been exchanging literary and romantic messages before her death. The combination of these things caused the media to pick up coverage of the case. Quickly, it gained widespread national attention.

Salacious coverage by newspapers, particularly the New York Herald, led to the release of extensive details about the crime and ensuing trial. The crime’s legacy is still felt today with America’s seemingly endless obsession with true crime coverage and sensational murder details. Here are ten facts about America’s first nationally followed true crime story.

Related: Top 10 Famous People Who Got Away With Murder (Maybe)

10 The Suspicious Circumstances of Jewett’s Death

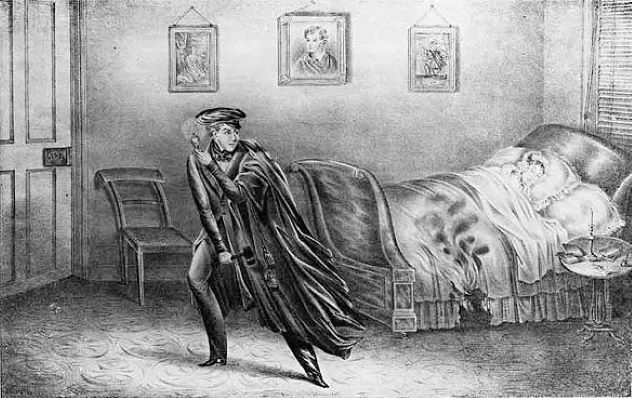

Very early on the morning of April 10, 1836, Rosina Townsend was awoken by the noise of a knock on her bedroom door. The brothel owner initially thought the sound was coming from a customer. So she stayed in bed and told the likely client to have his companion let him out of the locked house. When Rosina later got up to let another customer into the building, she noticed a lamp in the common room was out of place. Even more suspiciously, the back door had been left open.

Immediately, Townsend knew something strange had happened in her usually tightly-run brothel. As she made her way through the rooms, she came across her working women and their familiar clients. But trusting her gut on the matter, she searched for something else: an unwanted intruder.

As Townsend searched the house for intruders, she stumbled upon Jewett’s room. Unfortunately, the tiny corner room was filled with smoke. Immediately, she called out for help from local firefighters. Upon hearing the frantic cries of “fire,” watchmen rushed to the brothel. Townsend and another woman attempted to save anyone who might have been left inside the room amid the blazing inferno. Slowly making their way through the smoke, they were only able to find one person: Helen Jewett.

Sadly, she was already dead. Jewett’s body was found on the burning bed. It was charred from the fresh blaze. However, it was still intact enough to quickly reveal the three wounds on her head that investigators later believed likely caused her death. With that, New York police detectives had a sordid murder case on their hands.[1]

9 Jewett Herself Was a Mystery to Cops

Although the woman found dead in her bed was identified by Townsend and others in the brothel as “Helen Jewett,” that was not her real name. Like many sex workers of the time, she concealed some of her past and lived a life shrouded in mystery. Thus, it was difficult from the very start for the police to figure out her true identity. Those closest to “Jewett” in New York knew she had often lied about her past. Many people in her sphere believed she was really a woman named Maria Benson.

As that story went, “Maria” was supposedly an orphan who had been seduced and led into a life of immorality by the son of a well-known Boston merchant. But that story was likely false too. Historians now believe it was invented to evoke sympathy from paying clients. At the time, it perfectly fit the prevailing moral belief that young, innocent women were easily corrupted. So who was “Jewett” or “Benson,” anyways?

Investigators now believe the real identity of the murder victim known as “Helen Jewett” to be Dorcas Doyen, or possibly Dorrance. She was born in Maine in 1813. She was orphaned at a young age and taken in by a local judge. But some time later, she fled the area for New York. Once in the city, she took on the identity of Helen Jewett. Quickly, she caught on with the brothel as a sex worker.

For cops, it is possible Jewett’s past may have complicated matters. The police were not particularly concerned with finding out Helen’s true identity. For one, the murder of a sex worker was a low priority in the city. But giving Jewett a phony sob story background could have helped their case. So detectives preferred to keep her in the media as a mysterious, attractive murder victim. That, in turn, would gain public support for the search for her killer. As you’ll soon see, that tactic worked better than the cops could have ever imagined.[2]

8 Jewett’s Murder Shed Light on a Secret Lifestyle

Helen Jewett’s story quickly became well-known throughout the United States. However, she was not the only woman who rejected traditional moral values and forged her own path. In fact, there were so many women in similar situations that a group of them who worked in the sex industry in the early 19th century came to be known as the “frail sisterhood.” These women were not bound by the expectations and control of family or bosses. That system was most often the fate for women stuck in other occupations.

But in sex work, the frail sisterhood consisted of women who were at least able to control their own lives to some extent. Yes, they were still forced to operate within a patriarchal society that treated their bodies as commodities. For Jewett and her peers, the ability to strike out on their own terms to even the slightest degree was groundbreaking (and dangerous) at the time.

The sisterhood of sex workers was not limited to the urban environments of the northeast. In Nashville, there was a significant number of sex workers before and during the Civil War. They were so widespread, in fact, that Union leaders occupying the city saw prostitutes as a significant issue regarding the spread of disease and decreased morale among troops. Like many sex workers in the north, these women probably engaged in this work due to economic necessity.

Despite being an important part of their community, they were often viewed with moralistic judgment and scorn. But there was also a lurid quality to their work. Even though Americans may have said they were largely disgusted by these sex workers, they were fascinated by them, too. So when Jewett’s murder hit the newspaper headlines, it quickly became a scandal people couldn’t stop reading about.[3]

7 A Hasty Arrest Is Carried Out

“Frank Rivers” was the last known person to have been with Helen on the night of her death. According to brothel madam Rosina Townsend, Helen had ordered champagne for herself and her visitor. After delivering it, Townsend saw the man in bed with Helen. The madam thought little of the sight after bringing the bottle and glasses to her room.

But after Helen’s death, “Rivers” suddenly became a person of interest. After all, as far as Rosina knew, no one else had come to see Helen that evening. Even worse, “Rivers” seemed to have vanished before the events of the night played out. Still, police immediately knew he was likely to be a key person of interest in the investigation.

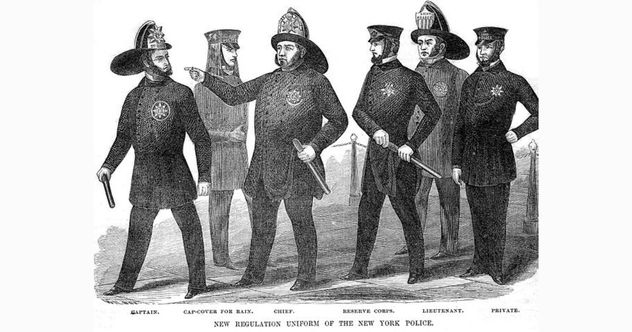

Soon, cops learned “Rivers” didn’t exist. Instead, they found their prime suspect in a young, well-off clerk named Richard Parmelee Robinson. Another sex worker in the brothel, Mary Cecilia Rogers, described the man she saw with Helen hours before the murder. Robinson fit the description perfectly. He also lived just half a mile south of the brothel where the attack happened. Plus, Richard was found to have white marks on his pants upon arrest. Some detectives believed those marks were from scaling a whitewashed fence near the scene.

Robinson was taken to the brothel to view Jewett’s body. Cops were hoping an attack of conscience would prompt him to confess. Unfortunately for them, he remained composed. Still, the witness statements of the women at the house proved decisive. Robinson’s roommate James Tew also gave cops info about Richard’s reportedly suspicious whereabouts that evening. The combination was enough to charge Robinson with murder. He was booked into jail to await trial.[4]

6 Richard Robinson’s Descent into the Underworld

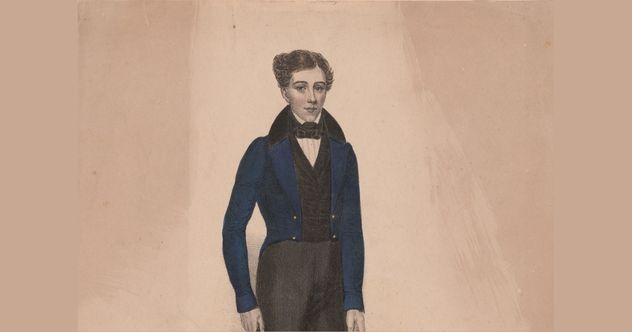

Richard Robinson came from a very wealthy New England family. In fact, his father was a notable Connecticut legislator. So it’s an understatement to say he was an unexpected suspect in a murder case. Robinson even leaned into that angle during his interrogation. While being questioned about Jewett’s death, he told police he thought he had “brilliant prospects” ahead in his life.

Thus, he claimed, he would not dare jeopardize it by committing murder. That he was accused of killing a sex worker was even more unlikely, he argued. But despite this, he was still charged with the crime. However, his reputation and the belief that he had a lot to lose by committing murder would later be considered during his trial. In fact, his high-class backstory may have influenced the verdict. And it certainly influenced press coverage during the case.

Already in his young life, Robinson had benefited greatly from his father’s connections. A strong education back in Connecticut gave him a background few had at the time. Financial resources and political connections were readily there for him. So it was confusing to his peers that Robinson would veer toward brothel life in New York City. Even that “Frank Rivers” pseudonym struck confusion in the hearts of those who supposedly knew him.

As police continued to investigate the case, more of Robinson’s dark side came out. Some accounts claim he met Jewett when he was still in his teen years. Regardless of his age, later in her short life, Helen appears to have had an ill-fated relationship with “Frank Rivers.” She wasn’t the only underworld character he was associated with, either. Robinson’s descent from elite Connecticut life to the mean streets of New York City was too salacious for newspapers to ignore. His dark side proved irresistible to the press—and the public ate it up.[5]

5 Sordid Sex Work and Intriguing Intellect Clash

In the 1830s in New York City, being a sex worker was a difficult profession. Women in this line of work faced the threat of violence at all times. They also faced severe social stigma and discrimination from the greater community. Even in the rough-and-tumble Five Points neighborhood, where many sex workers lived and worked, they struggled to make ends meet. Worse, they were very often treated as outcasts.

Despite these challenges, Helen Jewett’s murder somehow managed to capture the attention of reporters and editors at New York newspapers. They could not ignore her story. One editor even went so far as to visit the crime scene and examine the books found near her bed. The ensuing report can be directly linked to the image of Helen as an educated woman.

In fact, that seemingly minor detail about Jewett’s reading habits may have made her case sympathetic enough for New Yorkers to pay attention en masse. Among other women in the brothels, Helen had already been well-known for her beauty. But newspaper coverage soon depicted her as an intellectual, as well. She was well-read and articulate. Plus, she had a talent for writing, as demonstrated by old letters exchanged with Robinson.

The language in these letters was occasionally overly ornate. Both writers demonstrated their skill and education level by using flowery language to impress each other. In that regard, Helen stood out from what most people thought sex workers were supposed to be like. As newspaper coverage increased, Americans quickly recognized what they felt was Helen’s rare intellect. Almost overnight, a true crime sensation was born.[6]

4 Newspaper Coverage Hits a Fever Pitch

The coverage of the Helen Jewett murder was fraught from the start. Much of the newspaper reporting was marked by a tension between the morals of the Victorian Era and the public’s fascination with sensational sexuality. But even with that tension at play, it’s likely the case may have been completely forgotten if not for the New York Herald. Eager to expand its readership in the city, that newspaper brought Robinson’s trial to the forefront.

They published endless details of the case in inexpensive editions that were widely available across the Big Apple. Unfortunately, the reporting on the case often lacked integrity, especially by today’s standards. Historians now recognize that some of the Herald’s stories about the crime and trial were entirely fabricated. Others were based in fact but greatly sensationalized to stir up public emotion. Real news or not, the public loved it.

The Herald and other tabloids openly speculated about the motives behind Richard Robinson’s actions. One report claimed Richard was stealing money from his employer to spend on Helen. There was no evidence of this presented at the trial, but the paper’s bosses were unmoved. Others claimed Jewett threatened Robinson after learning of his plans to marry another woman.

Whether the allegations were true didn’t matter much to headline-chasing editors. The tabloids could attract significant attention and revenue by publishing endless articles about the case. The period leading up to the trial saw the Herald’s readership increase dramatically. Then, the week-long trial became a high point for the outlet’s circulation. In that sense, it’s no wonder the trial laid the path for the future of true crime. Suddenly, these cases were too sordid—and too lucrative—for the media to ignore.[7]

3 The Trial of the Century Begins

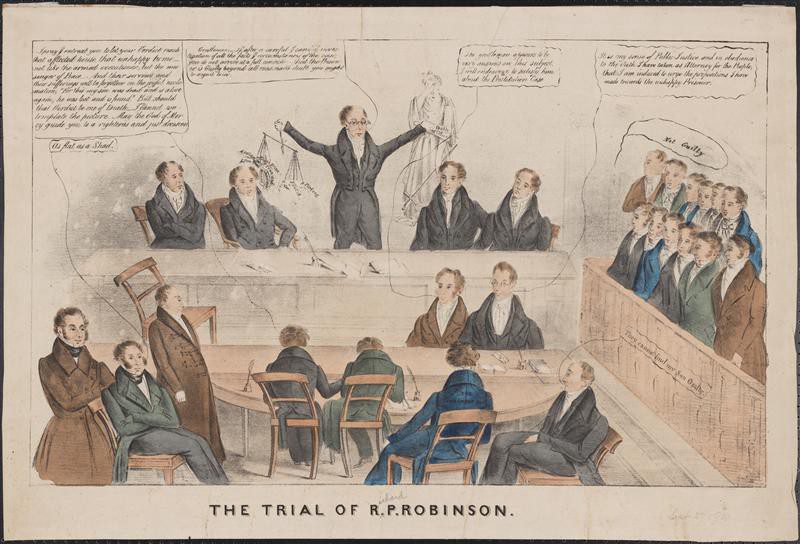

The murder trial of Richard Robinson began on June 2, 1836. The young store clerk with “brilliant prospects” faced down a jury of his peers in a week-long court battle that was remembered by witnesses decades later. Of course, he was accused of murder. But he had help in his corner. In addition to his well-connected father, Robinson’s employer, store owner Joseph Hoxie, hired a reputable lawyer to mount the young man’s defense. The courtroom was packed throughout the trial.

On the day of opening arguments, a crowd of nearly 6,000 people showed up. They had been stirred up by the intense media coverage of the case. Judge Ogden Edwards struggled to maintain order in the chaotic scene. Bailiffs provided additional security throughout the trial, but it didn’t help much. Amazingly, not enough jury members were present to sit in the box. So Judge Edwards ordered people from the crowd to serve on the jury. As it came out later, some of those jurors knew Robinson’s star witness.

When the trial finally began, several details about the night of the crime quickly came to light. First, the district attorney questioned Rosina Townsend. The brothel owner testified to finding Jewett dead in her bed. Townsend also testified that Jewett’s usual client for that night would have been a man named Bill Easy. However, she was certain Robinson was the last person to be seen with Jewett on the night of her death.

Other witnesses testified that the hatchet used in the crime resembled one Robinson used to open crates at his store. Still, others testified the other way, openly suggesting Jewett’s fellow sex workers were trying to frame the young man. Other pieces of circumstantial evidence were considered too. However, none could be definitively tied to Robinson.

In fact, what was likely the most damning evidence against him was never used. He supposedly sent threatening letters to Jewett before her death, as prosecutors were able to uncover. However, Judge Edwards granted a defense motion to suppress the letters’ existence. They were never entered into the court transcript, and jurors only learned of their existence after the trial.[8]

2 Robinson Gets Off—and Gets Out of Town

Everyone who followed the tense trial took sides. Some New Yorkers wore hats and ribbons to show their support for Robinson. Others wore different ribbons to indicate their backing of the murder victim. Jewett even gained some post-mortem notoriety after it was reported that other working women visited her bedside and stole pieces of charred wood as keepsakes. The trial saw lengthy closing arguments from both the prosecution and the defense. However, the jury didn’t need very long to close the case.

They reached a verdict of not guilty after only 15 minutes of deliberation. Now, we know it’s highly possible that the decision could have been influenced by the fact that some members of the jury were closely connected to Robinson’s witnesses. But the verdict stood, and the trial of the century was over. Robinson was released and left to live out the rest of his life. As fast as it had erupted, the media coverage died back down. No one else was ever investigated for Jewett’s death. To this day, the case remains unsolved.

Almost immediately after the trial, Robinson dropped his last name and changed his legal moniker to the slightly altered spelling “Richard Parmalee.” Then, he left New York and never looked back. Parmalee traveled halfway across the country to east Texas. Eventually, he settled in the town of Nacogdoches. There, he married and became one of the wealthiest people in the area. In some macabre sense, the “brilliant prospects” of his youth came true.

Regardless, Robinson died in 1855 while traveling along the Ohio River. To this day, some myths claim he mentioned Jewett’s name on his deathbed. There is no indication that it actually happened. Still, the legend remains. After death, Parmalee’s remains were later returned to Nacogdoches. He was laid to rest there in December 1855.[9]

1 Jewett Never Received Justice—but Her Legacy Remains

A few days after Helen Jewett was buried in St. John’s Cemetery, medical students exhumed her remains. Then, they dissected her body, presumably for science. But the media just couldn’t stay away. Right on cue, the New York Herald was there. They reported that the students turned Jewett into “an elegant and classic skeleton.” Even in death, Jewett’s story still sold newspapers. And she continued to make money for media outlets for years afterward.

Over the next several decades, her sordid passing was chronicled in various penny dreadfuls. Even 40 years later, she was still on the minds of New Yorkers looking to profit off her murder. In 1874, prominent New Yorker Charles Sutton published his memoir. The longtime warden of the New York Tombs wrote about Jewett in the book. It’s unclear whether he truly knew her, but Sutton acted like he did. He asserted the dead woman had been “radiant” and a “queen of the demimonde” during her life. Nearly half a century after her murder and trial, Jewett was still being used to draw attention from New Yorkers.

By the early 20th century, Jewett’s story had gone from salacious to outright false. Dime novels of the early 1900s attempted to re-tell the tale of her sad demise. But with every passing year, the stories got more fanciful and less honest. (Not that they ever were entirely truthful in the first place, thanks to the New York Herald. But we digress.) Of course, in the nearly two centuries since Jewett’s death, true crime content has only gotten more popular.

There are countless books, blogs, and podcasts that chronicle the grisly deaths of everyday citizens. Americans watch intently as cases go to court. Entire television networks have been founded to broadcast the most controversial trials. Through it all, viewers dissect the daily investigative updates obsessively with each other on social media. And to think it all began with the unsolved death of a New York sex worker way back in 1836…[10]