Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

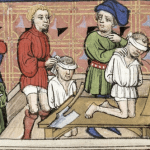

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Fascinating Laws That Are Neither Scientific nor Legal

“Law” can have several different meanings in the modern world. On the one hand, there is the kind of law that is enforced by the authorities, which can be long-armed, laid down, and fought (although a few singers have taught that the latter is not usually a good idea). People choose and apply the consequences themselves, but provided that they always do, then they form rules that will always hold.

On the other hand, there are scientific laws. These are rules that should hold true even without human intervention. However, people also apply the word to rules that seem to often be true, even if they have not been rigorously tested. These are usually named after the first or most famous person who notices them. Technologists like Bill Gates, writers like Arthur C. Clarke, and many others outside of the legal system and the hard sciences have all had so-called laws named after them. Read on to find out what they observed and how people use these laws to make predictions and decisions.

Related: Top 10 Outdated Laws You Didn’t Know You Were Breaking

10 Betteridge’s Law of Headlines

“Do Pineapples Make Great iPhone Cases?” was a question that the website Popular Science once asked its readers in a headline. Everyone can probably guess the answer. (No, just in case anyone was wondering.) But while this example was particularly obvious, not all polar-question headlines have such easy answers. Or do they?

According to British technology journalist Ian Betteridge, assuming the answer is “no” in every case would actually give people the right answer almost every time. The maxim has become known as “Betteridge’s Law of Headlines.” He believes that the reason it works is because such headlines are used to allow journalists to publish stories that they know are probably not true or that are lacking in facts and sources.

Betteridge first mentioned it in a 2009 article criticizing a technology news website that had helped spread a false rumor about another site by using a question headline. However, he was not the first to spot this useful rule. The veteran British journalist Andrew Marr also advised people to “try answering ‘no’” to question headlines back in 2004.[1]

9 Clarke’s First Law

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines is useful, but most people today know that misinformation and fake news are out there. However, even though people are somewhat skeptical of journalists, it is hard not to take a distinguished and elderly scientist at his or her word.

However, the science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke believed that when it came to predicting what scientific developments lay in the future, such scientists were often wrong. In fact, they were very consistent in what they got wrong. This was explained in the first of Clarke’s three laws, which says that “When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.”

This appeared in a 1962 essay he wrote, which blamed failure of imagination for poor predictions about the future. In 1977, another famous science fiction writer, Isaac Asimov, proposed an exception to Clarke’s law. He thought that when the general public passionately supports an idea denounced by elderly scientists, the scientists are more likely to be correct.[2]

8 Cunningham’s Law

Betteridge’s and Clarke’s laws give people an indication of when they can trust the information they are being told and when they ought not to rely on it. Cunningham’s law is similar but more practical and proactive. It can be used to help people get information they would like to know from others online, and it is said to be even more effective than simply asking.

According to Cunningham’s law, a false statement is more likely to be corrected than a straightforward question to be answered. So when there is something that people need to know, the best thing to do is basically to log on and make an authoritative but completely false declaration about their desired topic. Then, they can sit back and watch the corrections roll in.

The so-called law takes its name from Ward Cunningham, who knows a thing or two about gathering information as one of the most important developers of user-edited “wiki” websites. He was not, however, the first to put this law to use. Socrates, the ancient Greek philosopher, used to open some of his famous dialogues with arguments that he knew were wrong.[3]

7 Andy and Bill’s Law

Computers have inspired many other so-called laws besides Cunningham’s. Probably the most famous is Moore’s law, which predicts that the number of transistors on computer chips will double roughly every two years. What this really means is that computers get more efficient—processing faster and costing less—very quickly. It is named after Gordon Moore, who co-founded Intel, but he would not be the only executive of that company to have his own law.

Intel’s former CEO Andy Grove also has one, although he shares it with another tech visionary—Microsoft founder Bill Gates. “Andy and Bill’s Law” predicts that the gains achieved by chip manufacturers like Intel will be wiped out by developers like Microsoft, who expand their software to use up the available power.

As an old computer conference joke puts it, “What Andy giveth, Bill taketh away.” In some variations, it is Gordon Moore who “giveth,” but the joke disguises the astounding impact Bill and Andy’s law has had on the world. Continual innovation on both sides is the reason today’s smartphones have more computing power than the spacecraft that took men to the Moon in 1969.[4]

6 Eroom’s Law

Moore’s Law has held up pretty well since it was first described in 1965. It has led to great advances in technology, which should theoretically benefit other areas, helping them improve exponentially, too. However, when a 2012 study looked into whether gains in technology had benefited the development of new drugs, they found that the opposite had happened. The number of approved new drugs for every billion dollars spent on research has halved around every nine years since 1950.

That means that the cost of developing a new drug effectively doubles every nine years. The researchers called this “Eroom’s law,” Eroom being Moore spelled backward. One of the reasons they thought this happened was the “better than the Beatles problem.” This means that the amount of improvement required for approval is too high, like how there probably would not be much music today if every musician had to be much better than the Beatles and was forced to quit if they were not.[5]

5 Goodhart’s Law

Goodhart’s Law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Actually, that is how the anthropologist Marilyn Strathern rephrased the less concise original. Named after the British economist Charles Goodhart, a good example of this law comes from the attempt to solve a rat infestation in Vietnam in the early 20th century.

Rat catchers were hired to go down into Hanoi’s sewers, and to make sure that they were doing their jobs, they had to bring the tails of the rats they killed to the officials. This was a measure; the officials could count the tails to know how many rats were being killed. But then they decided to pay the rat catchers based on how many tails they brought in.

From then on, it was a target. The catchers stopped killing the rats and instead just removed the tails. That way, they could get paid, and the rats could reproduce so the catchers could get paid again the next day. Counting the tails was no longer an accurate measure of the rat-catchers’ effectiveness.[6]

4 Segal’s Law

Some laws are not really laws at all and would probably be better described as adages or proverbs. Segal’s law is an example of this. It states that “a man with one watch knows what time it is; a man with two is never sure.” On the surface, it points out the pitfalls of having too many sources of information. If they conflict with each other, people are unable to use either of them because they do not know which one is correct. It is, therefore, easier to have only one source, but wise people will note that it is then hard to tell if it is wrong.

Surprisingly, the earliest record of the saying comes from a San Diego newspaper in 1930, where it was a quip used to fill space. It takes the name “Segal” from a radio broadcaster in Texas called Lee Segall, to whom the quote was wrongly attributed in a popular book called Murphy’s Law. The author also misspelled his name. Segal’s Law has also been attributed to Mark Twain and Einstein. However, there is no evidence that it came from either.[7]

3 Benford’s Law

Imagine taking a stack of newspapers and noting down the first digit of every number reported in them. It would be reasonable to expect that each possible first digit appears roughly the same number of times. But according to Benford’s law, that is very unlikely. Lower first digits actually appear far more often than higher ones.

The phenomenon was first recorded by the astronomer Simon Newcomb in 1881. While flicking through a book of mathematical tables in the library, he noticed that the pages near the beginning were dirtier than those near the end. It seemed his colleagues preferred numbers that started with 1.

In 1938, the American physicist Frank Benford tested this further, using thousands of pieces of data. He found that smaller first digits really did appear more often, and Benford’s law has since been observed in all kinds of things, from electricity bills and street addresses to stock prices and population numbers. Today, Benford’s law is even used to help spot fraud. People making up numbers that they want to look random often try to use each digit equally so their figures will not obey Benford’s Law.[8]

2 Benford’s Law of Controversy

Even though it is also named after a man called Benford, who also happens to be a physicist, “Benford’s Law of Controversy” is not at all related to Benford’s Law. The Benford of the former is an astrophysicist called Gregory Benford, and his law teaches that “passion is inversely proportional to the amount of real information available.” When solid facts are in short supply, people tend to fill in the gaps with theories or rumors. They often choose what they would like to be true or what fits with their tribal identity.

This is why people can get so passionate about things that they do not really know about. This affects some people more than others, but it can happen to anyone. The reason the gaps are filled in in the first place is that uncertainty is an unpleasant feeling. Coming up with a narrative that explains everything, even if it is wrong, makes people feel better.[9]

1 Hofstadter’s Law

The causes of Benford’s Law of Controversy might be unconscious, but if people are aware of it, then they might be able to introspect and spot where their emotions are filling in the gaps. But trying to work around this final law promises to be a futile endeavor. That is because, according to Hofstadter’s Law itself, even knowing it will not help somebody to break it.

The self-referential law, which was thought up by the cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter, posits that planned tasks will always take longer than people expect—even if they take Hofstadter’s law into account. People already know that things take longer than they predict, so they adjust their estimate to give themselves even longer. But according to Hofstadter, they are doomed to be surprised once again.

Probably the most famous example of this law in action is the decade-long disaster of a project that was the Sydney Opera House. Similarly, London’s Wembley Stadium was expected to open in 2003, 2005, and 2006 before it eventually opened in 2007.[10]