Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Wildly Eccentric Classical Geniuses

“Have I gone mad?” asked the Mad Hatter. “I’m afraid so,” replied Alice. “You’re entirely bonkers. But I’ll tell you a secret. All the best people are.”

As we’ve noted before, creative people are a strange lot. They have schizotypal personalities, which can take a variety of forms, such as unusual perceptual experiences, a preference for solitary activities, or mild paranoia. Geniuses don’t all have personality disorders, of course. This is just a piece of the puzzle of why creative people tend to be eccentric. The complete answer is much more complex.

10Demosthenes

384–322 B.C.

The Athenian statesman Demosthenes, considered the greatest Greek orator, used his gifts to oppose the tyrants Philip of Macedon and Alexander the Great. Plutarch, in his work Parallel Lives, recounts that Demosthenes was inspired to become an orator when he heard the lawyer Callistratus make a plea in court on behalf of a client. So brilliantly did Callistratus make his case that it inflamed a desire in the young Demosthenes to take up oratory himself.

But the man had some pretty intimidating roadblocks to overcome. As Plutarch describes it, Demosthenes had “a certain weakness of voice and indistinctness of speech and shortness of breath, which disturbed the sense of what he said by disjoining his sentences.” His initial forays into public speaking were greeted with laughter, and Demosthenes resolved to overcome his impediment with measures like practicing speaking with his mouth full of pebbles.

More than that, Demosthenes worked to discipline himself not to get distracted. For this purpose, he built himself an underground study where he worked on his voice for two- or three-month stretches at a time. To fight off the temptation to hang around and do other things elsewhere, he shaved half his head of hair. This ridiculous hairdo had the effect of making him too embarrassed to show himself in public, thus forcing him to remain in his subterranean chamber and continue his regimen.

9James Joyce

1882–1941

If you were frustrated by the virtually indecipherable Finnegan’s Wake, consider the conditions under which it was written. Its author, James Joyce, was nearly blind.

He was only six years old when he received his first pair of eyeglasses. At 25, he was diagnosed with iritis, a painful and potentially blinding inflammation of the iris. For the rest of his life, Joyce had to undergo numerous failed operations to repair one or the other of his eyes.

Joyce’s odd writing habits were therefore done out of necessity rather than from personal quirks. His sister Eileen says Joyce would go to bed at night and write while lying on his stomach and wearing a white coat. Eileen realized later that the white coat was used to reflect light onto the paper to aid Joyce’s impaired eyes.

Joyce wrote Finnegan’s Wake this way, using a large blue pencil. That’s right: Joyce didn’t use a typewriter. He favored quality of writing over speed. Asked once how his novel Ulysses was getting along, Joyce said that he had been at work all day. The output of a day’s work? “Two sentences,” said Joyce. “I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in a sentence.”

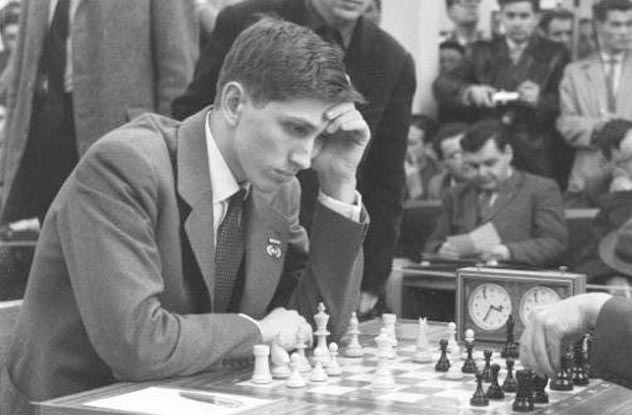

8Bobby Fischer

1943–2008

Even people with no interest in chess recognize the name Bobby Fischer. The American “Bad Boy of Chess” captivated his generation with his brilliance, having become the youngest grandmaster ever at age 14. Fischer then single-handedly ended Soviet dominance of the game by winning the 1972 World Chess Championship from Boris Spassky.

Always paranoid about Soviet cheating, he reportedly had the fillings removed from his teeth to prevent the Russians from transmitting secret messages. Fischer’s odd behavior showed itself to the world in that match. He constantly complained about his chair, the lighting, and the TV cameras. A dispute about the cameras and the game clock made Fischer refuse to play the second game.

This was not the first time Fischer’s petulance cost him a game due to forfeit. In his match against Samuel Reshevsky, play was reset for the following morning because Reshevsky, an Orthodox Jew, would not play on the Sabbath. Contending that he didn’t play mornings, Fischer let the game—and the match—go by default. Ironically, Fischer himself would later adopt Saturday as the Sabbath and refuse to play on that day, which resulted in his leaving a 1967 tournament while in the lead.

It was a testament to Fischer’s genius that he managed to come back from 0–2 to beat Spassky in that later championship game. He immediately gave $90,000 of the prize money to the Worldwide Church of God, a Pasadena-based cult he had joined. Like the rest of the church, he was taken in by the predictions of its leader, Herbert W. Armstrong, that Jesus would return in 1975 after a nuclear war. Fischer made Pasadena his home for the next several years and was once mistakenly arrested for robbing a bank, leading him to pen a pamphlet titled “I Was Tortured in the Pasadena Jailhouse.”

In 1992, Fischer defied UN sanctions against Yugoslavia by playing a rematch there against Spassky. Earning an indictment from the US government, Fischer spent his remaining years in exile. Right after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Fischer exultantly broadcast from the Philippines, “This is all wonderful news.”

7Jack Kerouac

1922–1969

If James Joyce’s painstaking writing habit did not lend itself to the use of a typewriter, the opposite was true for American novelist and poet Jack Kerouac. In 1951, after amassing copious notes in his journals, Kerouac let it all out in one feverish burst of creativity, resulting in his most famous work, On The Road. Kerouac didn’t want the creative flow to be sidetracked by his stopping to reload the typewriter at the end of each page. So he taped all the blank pages together into one long, continuous scroll so he could fire away at a rapid pace without pausing.

Quite predictably, his editor, Robert Giroux, was appalled when he saw the manuscript. “Jack, you know you have to cut this up,” Giroux said. “It has to be edited.” Kerouac stormed out of the room in a rage. It would be six years before On The Road was published. The scroll was later exhibited to record crowds at Kerouac’s hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts.

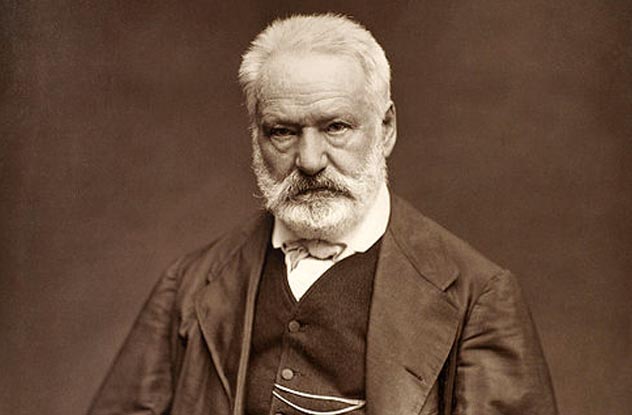

6Victor Hugo

1802–1885

While Demosthenes overcame distractions by shedding half his hair, renowned French novelist Victor Hugo did it by shedding his clothes. The author of such classics as Les Miserables devised this foolproof plan to force himself to meet the February 1831 deadline for The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Hugo locked away all his formal wear and ordered his servants not to give him any until he had finished the novel. He then stripped down and locked himself in his room.

But the story that he wrote completely in the nude is a myth. Hugo wore a large gray shawl, which he had purchased for the occasion. It reached down to his toes and was his only clothing for the rest of his self-imposed imprisonment. The technique worked, and Victor Hugo was able to finish Hunchback weeks before the deadline.

5Marcel Duchamp

1887–1968

French Surrealist Marcel Duchamp already had many weird inclinations as an artist, with his promotion of “readymade” art—everyday objects presented as exhibits. One of these was named “Fountain.” It was a urinal Duchamp had purchased.

But in his late twenties, Duchamp underwent a transformation. In the midst of career success, he abandoned art to play chess. To appreciate the impact of this move, author David Shenk says, “Imagine John F. Kennedy chucking politics in June 1960 in favor of billiards.”

Duchamp was so obsessed with chess that his days were spent in endless games or studying chess problems. His friends were shocked. “I play day and night,” Duchamp said. “Nothing interests me more than to find the right move.” In Paris, his typical schedule (when not playing against an opponent) was to work on chess problems all evening, take a short break at midnight with scrambled eggs at the Cafe Dome, and then go back to his room to study again until about four in the morning. “Everything around me takes the shape of the knight or the queen,” Duchamp said, “and the exterior world has no other interest for me other than its transformation into winning or losing positions.”

Even marriage to the young heiress Lydia Sarazin-Lavassor could not take him away from the iron grip of the game. On their honeymoon, he did nothing the entire week but study chess problems. The neglected wife soon could no longer stand it. One night, when Duchamp finally drifted off to sleep, Lydia glued all of the chess pieces to the board in an act of revenge. Three months later, she and Marcel divorced.

4Salvador Dali

1904–1989

Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali was famous for flaunting his eccentric persona for all the world to see. Even while a student in Madrid, he drew attention to himself by growing his hair long, sporting sideburns, and wearing stockings and knee breeches.

Later in life, it would be Dali’s signature outrageous mustache—long, waxed, and pointed upward to reach to his eyes—that made his face iconic. Dali explained, “Since I don’t smoke, I decided to grow a mustache. It is better for the health. However, I always carried a jewel-studded cigarette case, in which, instead of tobacco, were carefully placed several mustaches, Adolphe Menjou-style. I offered them politely to my friends: ‘Mustache? Mustache? Mustache?’ Nobody dared to touch them. This was my test regarding the sacred aspect of mustaches.”

Sometimes, he would carry a little silver bell. He would ring the bell to call people’s attention to his mustache.

Along with his glorious mustache, Dali often appeared in public in a flowing cape and walking stick, but those were mundane compared to his appearance at a ball held in his honor. There, Dali wore a glass case which contained a bra across his chest. He attended another event, the London International Surrealist Exhibition, in a diving suit, carrying a billiard cue, and accompanied by a pair of wolfhounds. Dali said his costume was a way for him to show that he was “plunging into the depths” of the human mind. He delivered his lecture in the diving suit and later had to be rescued from suffocating.

The eccentricity also spilled over to television. Dali kept referring to himself in the third person during an interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes. Asked which contemporary painters he admired most, he said, “First, Dali. After Dali, Picasso. After this, no others.”

3Henry Cavendish

1731–1810

The English chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish discovered hydrogen, described the composition of water, and accurately measured the density of the Earth. People also described him as one who suffered from shyness to a degree “bordering on disease.” He was so extremely introverted that he would rather credit other scientists for his observations than publish them himself.

Cavendish was so uncomfortable around people that he would literally flee when someone accosted or greeted him. During dinners at the Royal Society, which were the only social functions Cavendish attended, guests were advised not to approach or even look at him, in deference to his shyness. Female company in particular caused him “extreme distress.” Unsurprisingly, he never married.

He had only a housemaid to keep his home, and Cavendish didn’t relish any contact with her. All their communications took the form of written notes. To further reduce the chances of his running into other members of the human species, Cavendish had secret staircases built in his home so he wouldn’t have to use the regular corridors and hallways.

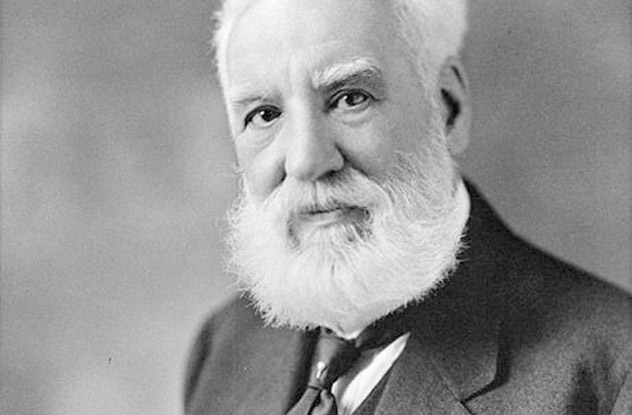

2Alexander Graham Bell

1847–1922

Whether or not he really did invent the telephone, Scottish-born Alexander Graham Bell was still a genius in many ways. His phone was actually the culmination of his experimentation on hearing devices—work Bell embarked upon to help his mother and wife, who were both deaf.

Bell’s grandfather had impressed upon him the importance of speech as a defining characteristic of humans. Bell was particularly intrigued by a talking automaton his grandfather took him to visit. When bellows forced air through the machine’s windpipe, a very distinct “Mama” was produced from the automaton’s suitably formed lips. Bell realized, “If vowel sounds could be produced by electrical means, so could consonants, so could articulate speech.”

Bell tried to replicate the workings of the talking automaton on a live subject, his Skye terrier Trouve. First, he taught the dog to growl continuously. Then, Bell would reach down to Trouve’s mouth and manually manipulate its lips and vocal cords. This method produced crude sounds, which delighted family guests. Bell finally had a “talking dog” who could ask, “Ow ah oo ga ma ma,” which the sufficiently imaginative could interpret as: “How are you, grandmama?”

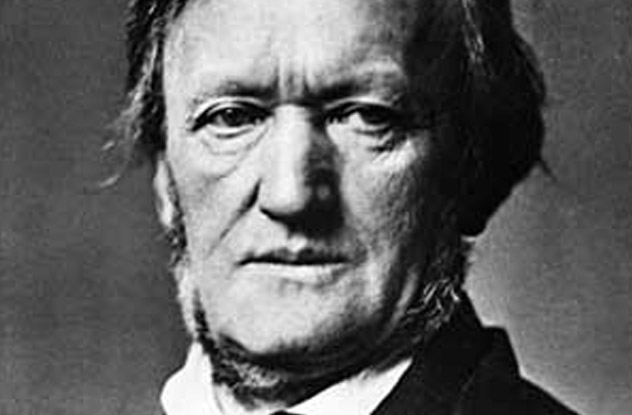

1Richard Wagner

1813–1883

German composer Richard Wagner, a colossus in the world of opera, made revolutionary contributions to the development of harmony and musical drama. His most towering work was Der Ring Des Nibelungen (“The Ring of Nibelung”), an epic retelling of Germanic mythology in four monumental operas.

Eminently successful in public, Wagner enjoyed domestic tranquility in the company of his dogs, which were his pride and joy. Two of them, Russ and Koss, accompanied him on daily walks. Russ was eventually buried at Wagner’s feet at his gravesite. But his most beloved dog was perhaps a King Charles spaniel named Pep. It was one of the few creatures to whom Wagner exposed his innermost thoughts.

Pep would respond naturally to his master’s changing tone of voice with corresponding jumping and barking, but Wagner discovered something more. It began to appear that Pep was sensitive to the emotional tone of music. Wagner noticed that the dog would respond differently to certain melodies and musical phrases as he sang or played them on the piano. For instance, certain passages in E-flat major elicited a calm tail wag from Pep, while passages in E major caused him to stand up in excitement.

Wagner discovered, through Pep’s consistent reactions, that he could associate specific musical keys with particular moods and emotions in drama. So Wagner drafted the dog Pep to co-write his next two operas, Tannhauser and Lohengrin. Pep had his own stool next to Wagner’s piano, and whenever the composer was having trouble with a passage, he would turn to Pep for his reaction and rewrite the piece according to the dog’s directions.

Thus, Wagner was able to achieve the effect, in Tannhauser, of having E-flat major convey the mood of holy love and salvation and E major suggest sensual love and debauchery. In Lohengrin, individual characters were associated—with Pep’s help—not only with particular musical keys but also with specific musical instruments and themes.

+Friedrich von Schiller

(1759–1805)

Poet, playwright, and philosopher Friedrich von Schiller was Germany’s most famous Romantic thinker. He penned the lyrics to the modern European anthem “Ode to Joy,” which was set to music by Ludwig van Beethoven. His revolutionary spirit influenced successive generations of philosophers, notably Friedrich Nietzsche.

A prolific writer himself, Schiller promoted the works of other contemporary authors, and this led to friendships with the most famous literary figures of the day. One of his good friends was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the writer of Faust. One day, Goethe paid a visit to Schiller’s home, but he arrived when the host was not around. He decided to await Schiller’s return by busying himself at his friend’s writing table. Goethe was not long seated when a strange smell assailed his nose. It gradually increased until he nearly fainted.

Goethe traced the “dreadful odor” to the drawer beside him. Opening it, he discovered to his astonishment that it was full of rotting apples. Goethe staggered to the open window and sucked in the fresh air. At this point, Frau Schiller came in and explained that her husband always kept rotten apples in his drawer “because the scent was beneficial to Schiller, and he could not live or work without it.”

There might be scientific logic behind Schiller’s apparently insane habit. Modern researchers have found that different scents have significant effects on the brain. Schiller may just have stumbled upon one that worked magic for his creative juices.

I enjoy studying history, playing chess and writing in my spare time. My book The Chess Workout is available for sale on Amazon.