History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

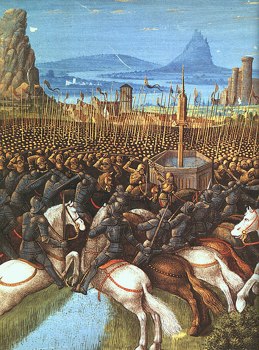

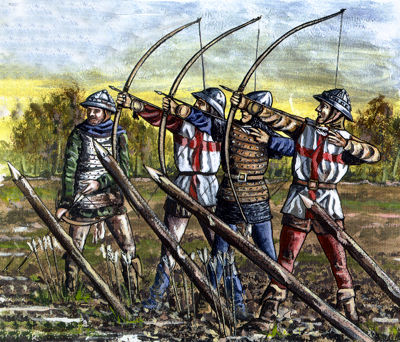

12 Most Impressive Medieval Soldiers

War was a common pastime in the middle ages. Nations battled nations, cities battled cities, and villages battled villages. It is no wonder that it is the period that generated some of the greatest soldiers and military units in history. This is a list of the best of the best – the 12 most impressive soldiers of the middle ages.

A mamluk was a slave soldier who converted to Islam and served the Muslim caliphs and the Ayyubid sultans during the Middle Ages. Over time, they became a powerful military caste often defeating the Crusaders. On more than one occasion, they seized power for themselves; for example, ruling Egypt in the Mamluk Sultanate from 1250–1517. After mamluks had converted to Islam, many were trained as cavalry soldiers. Mamluks had to follow the dictates of furusiyya, a code that included values such as courage and generosity, and also cavalry tactics, horsemanship, archery and treatment of wounds, etc.

The Janissaries comprised infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan’s household troops and bodyguards. The force was created by the Sultan Murad I from Christian slaves in the 14th century and was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 with the Auspicious Incident. Initially a small compact force of elite troops, they grew in size and power during the five centuries of their existence until they eventually became a threat to the fabric of the Ottoman empire. In their later years, they mutinied whenever an attempt was made to reform them, deposing and murdering those sultans they regarded as enemies.

The bill was a polearm used by infantry in Europe in the Viking Age by Vikings and Anglo-Saxons as well as in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. It was a national weapon of the English, but was also common elsewhere, especially in Italy. Derived originally from the agricultural billhook, the bill consisted of a hooked chopping blade with several pointed projections mounted on a staff. The end of the cutting blade curves forward to form a hook, which is the bill’s distinguishing characteristic. In addition, the blade almost universally had one pronounced spike straight off the top like a spear head, and also a hook or spike mounted on the ‘reverse’ side of the blade. One advantage that it had over other polearms was that while it had the stopping power of a spear and the power of an axe, it also had the addition of a pronounced hook. If the sheer power of a swing did not fell the horse or its rider, the bill’s hooks were excellent at finding a chink in the plate armour of cavalrymen at the time, dragging the unlucky horseman off his mount to be finished off with either a sword or the bill itself.

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian, Kievan Rusian, Bulgarian, Wallachian, and Moldavian aristocracies, second only to the ruling princes (in Bulgaria Emperors), from the 10th century through the 17th century. The rank has lived on as a surname in Russia and Finland, where it is spelled “Pajari”. Boyars wielded considerable power through their military support of the Kievan princes. Power and prestige of many of them, however, soon came to depend almost completely on service to the state, family history of service and to a lesser extent, landownership. Ukrainian and “Ruthenian” boyars visually were very simillar to western knights, but after the Mongol invasion their cultural links were mostly lost.

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, commonly known as the Knights Templar or the Order of the Temple, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders. The organization existed for approximately two centuries in the Middle Ages, founded in the aftermath of the First Crusade of 1096, with its original purpose to ensure the safety of the many Christians who made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem after its conquest. Officially endorsed by the Roman Catholic Church around 1129, the Order became a favoured charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades. Non-combatant members of the Order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom, innovating financial techniques that were an early form of banking, and building many fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land.

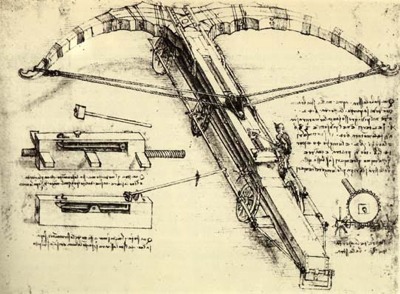

A crossbow is a weapon consisting of a bow mounted on a stock that shoots projectiles, often called bolts. It was created in the Mediterranean and in China separately. A mechanism in the stock holds the bow in its fully-drawn position until it is shot by releasing a trigger. Crossbows played a significant role in the warfare of North Africa, Europe and Asia. Crossbows are used today primarily for target shooting and hunting. The use of crossbows in European warfare dates back to Roman times and is again evident from the battle of Hastings until about 1500 AD. They almost completely superseded hand bows in many European armies in the twelfth century for a number of reasons. Although a longbow could achieve comparable accuracy and faster shooting rate than an average crossbow, crossbows could release more kinetic energy and be used effectively after a week of training, while a comparable single-shot skill with a longbow could take years of practice.

Housecarls were household troops, personal warriors and equivalent to a bodyguard to Scandinavian lords and kings. The anglicized term comes from the Old Norse term huskarl or huscarl. They were also called hirth (‘household’) that referred to household troops. The term later came to cover armed soldiers of the household. They were often the only professional soldiers in the kingdom, the rest of the army being made up of militia called the fyrd, peasant levy, and occasionally mercenaries. A kingdom would have fewer than 2,000 Housecarls. In England there may have been as many as 3,000 royal housecarls, and a special tax was levied to provide pay in coin. They were housed and fed at the king’s expense. They formed a standing army of professional soldiers and also had some administrative duties in peacetime as the King’s representatives. The term was often used in contrast to the non-professional fyrd. As an army, the Housecarls were renowned for their superior training and equipment, not only because they constituted a standing army (an ad hoc fighting force of professional soldiers as opposed to militia), but also due to rigorous quality control. For example, one lord passed legislation requiring that all enlistees own a sword with a gold-inlaid hilt. This assured that enlistees were of the economic standing that would permit them to train without financial hindrance and purchase good quality equipment. The most famous army of housecarls is without a doubt the one employed by Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings.

The Varangians or Varyags, sometimes referred to as Variagians, were Vikings, Norsemen, mostly Swedes, who went eastwards and southwards through what is now Russia, Belarus and Ukraine mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. Engaging in trade, piracy and mercenary activities, they roamed the river systems and portages of Gardariki, reaching the Caspian Sea and Constantinople. Basil II’s distrust of the native Byzantine guardsmen, whose loyalties often shifted with fatal consequences, as well as the proven loyalty of the Varangians led Basil to employ them as his personal bodyguards. This new force became known as the Varangian Guard. Over the years, new recruits from Sweden, Denmark, and Norway kept a predominantly Scandinavian cast to the organization until the late 11th century. So many Scandinavians left to enlist in the guard that a medieval Swedish law stated that no one could inherit while staying in Greece. In the 11th century, there were also two other European courts that recruited Scandinavians: Kiev Rus c. 980-1060 and London 1018-1066. Steve Runciman, in “The History of the Crusades” noted that by the time of the Emperor Alexius, the Byzantine Varangian Guard was largely recruited from Anglo-Saxons and “others who had suffered at the hands of the Vikings and their cousins the Normans”.

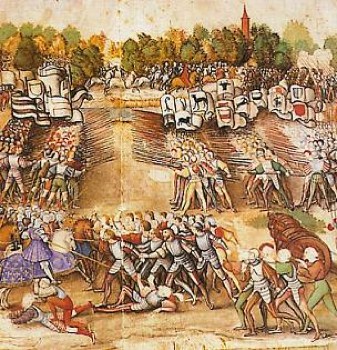

Swiss mercenaries were soldiers notable for their service in foreign armies, especially the armies of the Kings of France, throughout the Early Modern period of European history, from the Later Middle Ages into the Age of the European Enlightenment. Their service as mercenaries was at its apogee during the Renaissance, when their proven battlefield capabilities made them sought-after mercenary troops. During the Late Middle Ages, mercenary forces grew in importance in Europe, as veterans from the Hundred Years War and other conflicts came to see soldiering as a profession rather than a temporary activity, and commanders sought long-term professionals rather than temporary feudal levies to fight their wars. Swiss mercenaries were valued throughout Late Medieval Europe for the power of their determined mass attack in deep columns with the pike and halberd. Hiring them was made even more attractive because entire ready-made Swiss mercenary contingents could be obtained by simply contracting with their local governments, the various Swiss cantons, the cantons had a form of militia system in which the soldiers were bound to serve and were trained and equipped to do so. It should be noted, however, that the Swiss also hired themselves out individually or in small bands.

A cataphract was a form of heavy cavalry used by nomadic eastern Iranian tribes and dynasties and later Ancient Greeks and Romans. Historically the cataphract was a heavily armed and armoured cavalryman who saw action from the earliest days of Antiquity up through the High Middle Ages. Originally, the term referred to a type of armour worn to cover the whole body and that of the horse. Eventually the term described the trooper himself. While cataphracts and knights are given differing names, in battle the cataphract’s role differed little from that of the knight in medieval Europe, though arms and tactics still separated the two. Unlike a knight, a cataphract was merely a soldier off the battlefield and had no fixed political position or role beyond military functions.

A halberd is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 14th and 15th centuries. Possibly the word halberd comes from the German words Halm (staff), and Barte (axe). The halberd consists of an axe blade topped with a spike mounted on a long shaft. It always has a hook or thorn on the back side of the axe blade for grappling mounted combatants. It is very similar to certain forms of the voulge in design and usage. The halberd was 1.5 to 1.8 meters (4 to 6 feet) long. The halberd was cheap to produce and very versatile in battle. As the halberd was eventually refined, its point was more fully developed to allow it to better deal with spears and pikes (also able to push back approaching horsemen), as was the hook opposite the axe head, which could be used to pull horsemen to the ground. Additionally, halberds were reinforced with metal rims over the shaft, thus making effective weapons for blocking other weapons like swords. This capability increased its effectiveness in battle, and expert halberdiers were as deadly as any other weapon masters were. It is said that a halberd in the hands of a Swiss peasant was the weapon that killed the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, decisively ending the Burgundian Wars, literally in a single stroke. And finally, my own number 1 most impressive medieval military unit.. by far..

A longbow is a type of bow that is tall (roughly equal to the height of a person who uses it), is not significantly recurved and has relatively narrow limbs, that are circular or D-shaped in cross section. A Welsh or English military archer during the 14th and 15th Century was expected to shoot at least ten “aimed shots” per minute. An experienced military longbowman was expected to shoot twenty aimed shots per minute. A typical military longbow archer would be provided with between 60 and 72 arrows at the time of battle, which would last the archer from three to six minutes, at full rate of shooting. Thus, most archers would not loose arrows at this rate, as it would exhaust even the most experienced man. Not only are the arms and shoulder muscles tired from the exertion, but the fingers holding the bowstring become strained; therefore, actual rates of fire in combat would vary considerably. Ranged volleys at the beginning of the battle would differ markedly from the closer, aimed shots as the battle progressed and the enemy neared. Arrows were not unlimited, so archers and their commanders took every effort to ration their use to the situation at hand. Nonetheless, resupply during battle was available.

Young boys were often employed to run additional arrows to longbow archers while in their positions on the battlefield. “The longbow was the machine gun of the Middle Ages: accurate, deadly, possessed of a long range and rapid rate of fire, the flight of its missiles was likened to a storm.” This rate was much higher than that of its Western European projectile rival on the battlefield, the crossbow. It was also much higher than early firearms (although the lower training requirements and greater penetration of firearms eventually led to the longbow falling into disuse in English armies in the 16th century). Longbows were difficult to master because the force required to deliver an arrow through the improving armour of medieval Europe was very high by modern standards. Although the draw weight of a typical English longbow is disputed, it was at least 360 N (80 lbf) and possibly more than 650 N (143 lbf) with some high-end estimates at 900N (202 lbf). Considerable practice was required to produce the swift and effective combat shooting required. Skeletons of longbow archers are recognizably deformed, with enlarged left arms and often bone spurs on left wrists, left shoulders and right fingers.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia