Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Worst Aircraft of World War 2

There are countless books, dvds and websites about the great aircraft of World War Two. Almost everyone would recognize the Spitfire, P-51 Mustang, Me109 or Lancaster. However, there were hundreds of aircraft types used between 1939 and 1945, and, inevitably, some were abject failures. I’ve always enjoyed ‘worst of’ lists, and had an interest in aviation, so I thought it time to combine the two.

So what makes a bad aircraft? Is it the slowest, most outdated or poorest armed aircraft? It’s not that simple, as some aircraft massively overachieved despite being outdated (the Fairey Swordfish is a prime example.) So my criteria is simple: a bad aircraft is something that failed to do the job it was assigned to do. Some of the planes weren’t bad designs, just outdated. Others could have been great but were rushed into production and dogged by reliability issues. Others were simply bad full stop. Some you may know, but others have, quite rightly, faded into obscurity. There is a dark side to this list, as their deficiencies undoubtedly cost the lives of hundreds of young pilots. Although, on the other hand, you could also argue that in failing they could not inflict casualties themselves.

The first rule I had was that the aircraft had to have been used operationally, either for training or combat, as it’s pure speculation debating if a prototype would have been successful. The second was one entry from each of the major participants, if only for variety’s sake. There were still a surprising number of contenders for this list, so I have gone for those with an interesting story behind them, as reading “never saw combat and was used as a trainer” several times won’t be that interesting. This is the first list I’ve submitted, so feel free to comment.

First flown in 1936, the 3 seat Fairey Battle light bomber represented a major advance over its biplane predecessors. It was also the first operational aircraft to use the legendary Rolls Royce Merlin engine. Unfortunately, such was the pace of aircraft development during the late 1930s, that it was obsolete before it ever reached a squadron. Nonetheless, with war looming, the Air Ministry was intent on getting as many aircraft, regardless of capability, into service and full scale production was ordered.

At the outbreak of war ten RAF squadrons were sent to Northern France as part of the Advanced Air Striking Force. For the first 8 months engagements were limited, but the Battle did claim the RAF’s first victory of the war, when a rear gunner shot down a Messerschmitt Me 109. However when the Wehrmacht swept into France and the Low Countries on 10th May, 1940, the Battle’s flaws were horribly exposed. Its armament of two rifle calibre machine guns was hopeless against modern fighters, and its slow speed made it an easy target for AA gunners. 32 aircraft were sent on the opening day, of which 13 were lost, along with most of the 18 Belgium examples. The next day, 7 out of 8 were shot down, and on the 14th, 35 of 63 were lost in a desperate all out attack against German bridgeheads. In just a week, 99 aircraft were destroyed, taking with them large numbers of highly experienced aircrew, and failing to delay the German advance by a single hour.

This was, effectively, the end of the Battle’s front line career, and the survivors spent their days fairly peacefully as trainers or target tugs. Perhaps its most famous exploit was the 12th May attack by 5 Battles on the Albert Canal Bridge. Led by Flying Officer Donald Garland, the volunteer crews pressed home their unescorted daylight attack against terrifying odds. One span of the bridge was hit and briefly knocked out, but at the cost of all 5 aircraft. Both Garland and his navigator, Thomas Grey, received posthumous Victoria Crosses, the highest award for bravery a member of the British or Commonwealth armed forces can receive.

This list is in no particular order, however there is one aircraft that stands well above (or should that be below?) the rest. First flown in 1936, the sleek and elegant Lince (Lynx) scored a major propaganda victory for Mussolini’s regime when it set two speed over distance records. Its military potential was obvious, however the extra weight necessitated by the weapons, armor plating and equipment had a disastrous effect on its performance and handling.

First employed against French airfields in Corsica the type was found to be hopelessly underpowered and possessed terrible flight characteristics. Nonetheless, it was the only heavy fighter available to the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force), and a number were sent to North Africa. The addition of sand filters robbed what little power the aircraft had, to a point where it became virtually useless. An attack on a British airfield in September 1940, had to be aborted when the fully laden aircraft failed to reach operational height or maintain formation. From being a record setter, the Lince could now only reach half its claimed speed. Some sources even state the aircraft had to take off in the direction it wanted to travel, as it lacked the power to make a banking turn.

As a final ignominy, the survivors were parked up and used as decoys for attacking Allied aircraft. Others were scrapped straight from the factory, thus completing the career of quite possibly the worst aircraft ever to see combat.

Initially conceived as a passenger aircraft, the astonishingly ugly Zubr (Bison) was converted to a bomber as a backup, in case the somewhat more advanced PZL.37 failed. Romania also expressed an interest in this new design – that is until the aircraft, carrying two high ranking officers, broke apart in midair.

With war fast approaching, the Department of Aeronautics ordered Bristol Pegasus engines 50% more powerful than the prototypes. Experts warned that the airframe wasn’t strong enough, but the powers that be decided it was an acceptable risk. Subsequent examples were crudely strengthened by gluing extra plywood onto the wing spars, but a number of serious defects remained. Chief among these was the undercarriage, whose locking mechanism was extremely weak and unreliable, resulting in most aircraft flying with it fixed down. This, and the extra reinforcing, did nothing for the already poor performance and further reduced its payload.

It was recognized that the Zubr was completely obsolete, and hence assigned to training units. At full weight it could only be operated from paved runways, and even then could only carry a tiny bomb load. Most were destroyed on the ground during the opening days of the war, with Germany operating the few captured survivors. Ironically, they had a longer and more useful life in the hands of the Luftwaffe

Before the outbreak of war, Luftwaffe doctrine put great faith in Zerstörer (destroyer) aircraft; twin engined, long range heavy fighters. The resultant aircraft, the Me 110, would indeed prove a very effective bomber killer, so long as there were no escorting fighters. Even before war had broken out, work had already begun on its successor, designated Me 210. The new design, which flew the day after the invasion of Poland, was 50mph (80kph) faster, had a longer range and heavier armament. One very advanced feature was the use of side rear firing 13 mm (0.51 in) MG 131 turret guns (barbettes), controlled remotely by the rear crew member. The testing process was however fraught with difficulty; the prototype was highly unstable, prone to stalling and, despite a total of 16 redesigns, the problems were never adequately solved. The chief test pilot commented that the Me 210 had “all the least desirable attributes an airplane could possess.”

Despite the glaring deficiencies full scale production was ordered. So unpopular was the aircraft that its service life lasted little more than a month, by which time only 90 had been delivered. It was decided that production should be halted, and the Me 110 program restarted. The debacle badly hurt the reputation of the Messerschmitt company, and forced the 110 to solider on well past its sell by date. Most of the flaws were rectified in later models, yet such was its reputation that they was re-designated the Me 410 Hornisse (Hornet). These improved models initially faired well as bomber destroyers, but were shot down in droves when faced with P-47 and P-51 escort fighters.

This wasn’t quite the end the 210’s story, as it was also built under license in Hungary, who were then part of the Axis Powers. 267 further aircraft were built and supplied to the Hungarian Air Force and Luftwaffe. By all accounts the Hungarian pilots thought highly of the aircraft and used it extensively in the close support and dive bombing roles.

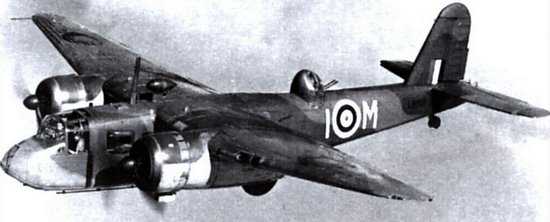

Conceived as a three seat torpedo bomber/reconnaissance plane, the Botha first flew on 28th December, 1938. Despite being inferior to its competitor, the Bristol Beaufort, in every respect bar service ceiling, both aircraft were ordered for production. The Air Ministry then dictated a fourth crew member should be added, further reducing the Botha’s already inadequate performance.

In addition to its underpowered engines, the aircraft became involved in an alarming number of fatal crashes. Very quickly it developed a reputation as a death trap and, in one especially grim episode, was involved in a mid air collision with a Defiant fighter. The stricken aircraft fell into Blackpool Central Train station, killing all five aircrew and thirteen civilians on the ground. Although this cannot be blamed on the shortcomings of the aircraft, it did nothing for its terrible reputation. Testing had proven the airframe extremely unstable and inadequate for front line service. One test pilot noted “that thing is bloody lethal, but not to the Germans, I never want to see it again”. Another famous quote “access to this aircraft is difficult. It should be made impossible” is also frequently attributed

Only one squadron ever used the Botha in front line operations. Even then it never dropped a torpedo in anger, instead being used mainly for patrols carrying anti submarine bombs. The type was declared unsuitable a few months later and replaced by the older, but trustworthy, Avro Anson, and then withdrawn to training units. Of the 473 aircraft assigned to training, 169 were lost in crashes. In this respect, it proved far more useful to the German war effort

During the inter war period, the Air Ministry pinned high hopes on two rather unusual fighters. The Boulton Paul Defiant and Blackburn Roc were single engined monoplanes built for the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm (the Royal Navy’s air force), respectively. Both aircraft concentrated their armament of 4×7.62mm (.303inch) machine guns in an electrically driven turret behind the pilot. The Roc was envisioned as a mobile observation post, engaging “fleet shadowing” aircraft that could report on ship movements whilst staying beyond the range of AA guns, or breaking up incoming torpedo and dive bomber attacks. It was also designed with a limited dive bombing capability of its own

In theory, the idea was sound. Two seater fighters such as the Bristol Scout had given excellent service in World War One, and had been a staple of the RAF in the inter war period. This arrangement would allow the pilot to concentrate on flying whilst his gunner could worry about firing, and also provide a defense against the classic diving attack. Once again, however, when faced with the harsh reality of modern war, it was exposed as a liability. The only way the gunner could get aim at an opposing fighter would be if the pilot flew straight and level, which in a dogfight is the very last thing you want to do. The aircraft lacked any forward firing guns, and the turret could not even fire head on. The Browning 7.62mm (.303 inch) was the standard RAF weapon for much of the war, but the rifle calibre bullets lacked stopping power against modern aircraft. It also proved almost impossible for the gunner to bail out of a stricken aircraft.

The Defiant saw far more combat and suffered very heavy losses once its Achilles Heel was discovered. However there is a reason the Roc is on the list and the Defiant isn’t. Despite the losses, the RAF’s version scored some early success and proved a reasonable night fighter during the early stages of the Blitz. The Roc on the other hand had a top speed of 160 kph (100mph) less, making it slower than most of the German bombers it was supposed to be shooting down. As a fighter it failed utterly, and in its career scored a grand total of one confirmed kill. The most useful task the Roc ever performed were the four examples parked up and used as permanent AA posts at Gosport airfield.

The world’s first and only operational rocket powered aircraft, the Komet was a point defence fighter whose performance was, quite literally, explosive. On paper it looked like a winner. It would streak into the sky to intercept American bomber formations and launch a diving attack at speeds well beyond any escorting fighters. Just a few rounds from its deadly twin 30mm cannons would be enough to destroy a four engined bomber, and plans were soon for hundreds of fighters to protect Germany’s industrial heartland. Testing proved encouraging with prototypes reaching speeds of 885kph (550mph)

In reality, the Komet was beset by problems. Although it was extremely fast, it only allowed the pilot a few seconds firing time, and the low rate of fire and muzzle velocity of the cannons made aiming extremely hard. Fuel was used up very quickly, after which the pilot had no option other than to glide back to base. The chief flaw, however, was the extremely volatile nature of the propellant. A hard jolt on takeoff or landing would cause the aircraft to explode, whereas if the fuel leaked it was quite capable of fusing flesh to steel. It didn’t even have a proper undercarriage, only a disposable wheeled dolly for take off and crude skid for landing. The Komet could also only take off in the direction the wind was blowing and the fuel lasted for 7 minutes 30 seconds at absolute maximum. One was sent to Japan but lost in transit, although the Japanese Army Air Force managed to built the Mitsubishi Ki-200 using only the instruction manual. It flew one test fight, crashed and the project was halted by the end of the war

Of all the Komets lost, 80% were in take off and landing accidents, 15% due to loss of control or fires, and the remaining 5% to Allied aircraft. Only one front line squadron was ever equipped with the Komet. They claimed 9 aircraft for the loss of 14.

As with the Fairey Battle earlier in the list, the Douglas Devastator represented a major advance on its predecessors. First flying in 1935, it was one of the first carrier based monoplanes, the first all metal naval plan and the first with a fully enclosed canopy. At this stage it was, arguably, the most advanced torpedo bomber in the world. By the time of Pearl Harbor it was, however, completely obsolete, yet with its replacement, the TBF Avenger, still in testing stages there was no alternative. With a top speed of 331kph (206mph) the plodding Devastator was gravely vulnerable to patrolling fighters. To make things even worse, the crude torpedoes it carried could not be released above 185kph (115mph) and often broke up or failed to explode. Testing had been carried out with dummy torpedoes with warheads filled with water, and little thought had been put in to how they would perform in combat.

In the initial stages of the Pacific War the Devastator performed fairly well, sinking 2 transports and a destroyer and contributing to the destruction of the carrier Shoho during the Battle of the Coral Sea. However, it was the decisive Battle of Midway where the aircraft would find infamy. Poor weather and a lack of co ordination meant the Devastator’s Wildcat fighter escort did not show up and its fate was sealed. VT-8 torpedo squadron pressed home their attack against the carrier Kaga, but having to fly straight and level with no escort, the result was a massacre. Patrolling Zeros quickly shot down all 15 aircraft with only a single airman later being plucked from the sea. Of the 41 Devastators deployed that day, only 4 would return and not a single torpedo hit its target. Their sacrifice wasn’t entirely fruitless, however; in drawing the defending fighters to low altitudes they allowed the Dauntless dive bombers a relatively clear run to sink 3 of the 4 Japanese carriers, and help turn the tide of the war. The few survivors were immediately withdrawn from service, and none survived beyond 1944.

Unlike its Western contemporaries the LaGG 3 fighter was designed to be built using “non strategic” materials. The structure was wooden covered with Bakelite lacquer, which meant it was not only cheaper than metal, but resistant to rot and fire. Originally designed with the new Ki-106 engine in mind, it had to switch to the lower powered Ki-105 when the new powerplant proved unreliable. As a result, it was simply too heavy for its own airframe. Nonetheless, it carried powerful armament and was certainly more advanced than any other fighter in the VVS (Soviet Air Force) inventory, and Stalin ordered mass production.

During the early stages of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR, the Luftwaffe simply ran riot over the poorly trained and equipped VVS. Stalin’s purges had left a crippled command structure unwilling or unable to react. German pilots began to rake up victories with such ease that they began to refer to it as infanticide. The LaGG was too slow and lacked a rate of climb necessary for an interceptor. Its handling was also taxing, and could enter a vicious spin if it turned too tightly. The wooden frame may have been strong but was too heavy and prone to shattering when hit by cannon fire. It became a deeply unpopular machine; the name was an abbreviation of the principal designers, but pilots grimly joked it stood for lakirovanny garantirovanny grob, or guaranteed varnished coffin.

6,258 versions had been built by the time production was halted. This was not, however, quite the end of the road for the LaGG family. Fitted a lightened airframe, cut down fuselage, and a more powerful radial engine it became the La-5, one of the best Soviet fighters of the war.

The final entry on our list, the MXY-7 Ohka (Cherry Blossom) wasn’t a plane as such, but a manned missile. By 1944, Japan was growing increasingly desperate to stem the Allied advance through the Pacific. The solution was a dedicated kamikaze craft, built out of non essential materials, and packing enough explosives to sink a heavily armoured warship. It was designed to be carried underneath the Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber. Once near the target it would be released, using its three rocket motors in a 1000kph (620mph) dive at enemy shipping. It was incredibly basic, the cockpit having just four instruments, but since it would only ever be a one way trip this was considered unimportant. Grand plans were put forward for waves of suicide aircraft to be launched from planes, submarines and even caves.

The Ohka was first used operationally on 21st March 1945, when 16 were carried by “Bettys” to attack US Navy Task Force 58. Pounced by patrolling Hellcats, the bombers released their cargo 113km (70 miles) from the targets. Not a single Ohka reached its target, and all 16 bombers, along with 15 of the 30 escorting Zero fighters, were shot down. On 1st April, the USS West Virginia was hit, suffering minor damage, but again all the Bettys were lost. They were employed a further 8 times before the end of the war. During these operations they sunk one destroyer and badly damaged two more, but at the cost of 50 Ohka and the majority of mothership bombers. Although extremely fast, it was almost impossible to aim at a moving target, lacked the power to cripple larger ships and was fatally vulnerable until it was launched. To the Americans it was nicknamed the Baka (fool or idiot). In Today’s Japan the kamikaze ethos is seen as a tragic waste of life, and Ohka pilots are honored in several shrines throughout the country. Such suicide attacks (mini submarines, small boats and divers were also utilized) did nothing to stop the Allied advance and merely served to harden their resolve to defeat Japan by whatever means necessary. This was undoubtedly a factor in the decision to use the atomic bomb to end the war.

As an aside, a similar version was also built in Germany as the Fiesler Fi-103. The main difference was this allowed the pilot scope to bale out after aiming his aircraft, although quite how you would successfully climb out at near the speed of sound with a pulse jet by your head is somewhat debatable. The idea of suicide corps was mooted, but Hitler rejected the idea believing it “wasn’t in the German warrior spirit”