Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Extremely Dramatic Mutinies From History

The most famous mutiny in history is the one on the Bounty, which we’ve covered before. It’s been immortalized on film, and understandably so, yet it is far from the only high-stakes capture of a ship that would be worthy of Hollywood. Naval history is full of murder, rebellion, and deceit—and these 10 stories are among the most intense examples.

10The Meermin Slave Mutiny

In January 1766, a Dutch East India Company ship called the Meermin left Madagascar carrying 147 slaves. The conditions were cramped, and the captain was concerned his cargo might not survive the journey, so he allowed some of the slaves on deck. One of the senior officers decided to take advantage of the opportunity and asked five of the slaves to clean some spears that the crew had taken as souvenirs. Handing five of the captives their own weapons went about as well as you’d imagine for the crew, and half of the Dutch sailors were killed. The remainder holed themselves up beneath deck and survived on raw bacon and potatoes.

The newly freed slaves had no idea how to sail the ship. They let out some of the crew members and ordered them to return the ship to Madagascar. Instead, the crew covertly sailed toward Cape Town. When land came into view, the slaves were somewhat suspicious. Rather than run the ship ashore, they threw down anchor. Seventy rowed to land, promising to light fires if it was safe for the rest to follow. Unfortunately for the mutineers, the sight of a ship harbored offshore without a flag had made local Dutch farmers suspicious. When the slaves made land, they were met by armed militia, and all were captured or killed.

The Dutch crewmen back on the ship dropped letters in bottles overboard. Among those that reached land was one that read: “Although we trust in the Lord to save us we kindly request the finder of this letter to light three fires on the beach and stand guard at these behind the dunes, should the ship run aground, so that the slaves may not become aware that this is a Christian country. They will certainly kill us if they establish that we made them believe that this is their country.”

Fires were lit on the shore, and the slaves on the ship took this as the signal. They ordered the Dutch to run the ship aground. When the Meermin got to the beach, it was stormed by armed Dutch, and the remaining slaves were recaptured. The leaders of the uprising, Massavana and Koesaaij, were imprisoned on Robben Island. Koesaaij survived there for 20 years. Less than 200 years later, the same island was used to imprison Nelson Mandela for 18 years.

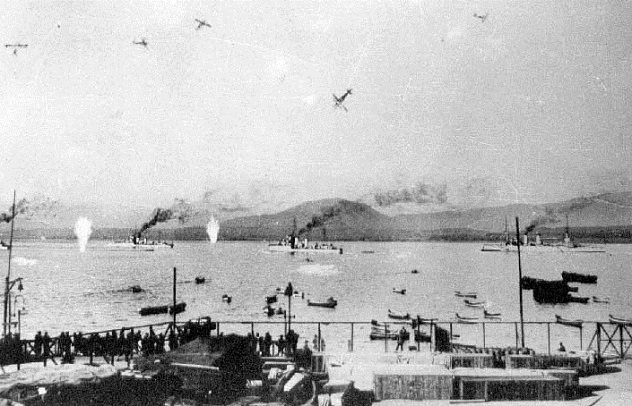

9The Mutiny On The Potemkin

The mutiny on the Russian battleship Potemkin in 1905 is perhaps the only one in history to have been triggered by a dispute over soup. On June 14, meat being used to create borscht for the crew was found to be riddled with maggots. The ship’s doctor said they were only flies’ eggs and that there really wasn’t a problem. The crew disagreed and sent a man named Valenchuk to have words with the ship’s commander, Giliarovsky. The commander didn’t react well to the confrontation—he pulled out his gun and shot Valenchuk dead. In retaliation, the crew threw Giliarovsky overboard and shot him before he had a chance to drown.

Tensions were high on the ship even before the soup fiasco. Russia was in the grip of revolution, and many of the sailors had sympathies in that direction. One of them, named Matyushenko, set up a “people’s committee” and took charge of the vessel. They sailed to Odessa, where protesters were flying the red flag. Locals gave the sailors food and brought flowers for Valenchuck’s impromptu funeral.

The funeral became a focal point for renewed violence. Soldiers began firing on the sailors, killing three. By the end of the day, another 2,000 locals were killed by the authorities. In retaliation, the Potemkin fired its guns at the local theater that was being used as headquarters by the army, but the shells missed.

Eventually, a task force was sent to recapture the battleship. However, the mission didn’t go as planned. Sailors on another vessel, the Georgii Pobedonosets, also mutinied and joined the Potemkin. This second mutiny came to a swift end the following day when loyal sailors retook control and ran their ship ashore.

After a week of playing cat and mouse, the crew of the Potemkin were unable to find anywhere to replenish their supplies, and they abandoned the ship in Romania. The Romanians gave the Russians their ship back. Matyushenko escaped but returned to Russia under a false name two years later. He was identified and arrested, eventually being hanged on October 20, 1907. The mutiny became part of revolutionary propaganda and was immortalized on film in 1925.

8The Mutiny On HMS Hermione

One of the most violent mutinies in British naval history took place on the frigate HMS Hermione in 1797. The ship patrolled the seas of the West Indies, captained by Hugh Pigot. He was cruel and violent, renowned for lashing his crew members for minor slights. The mutiny was dramatic but not surprising.

One night during a storm, the ship’s crew were working to bring in the sails. Unhappy with what he perceived as slow work, Pigot yelled that the last man down would be flogged. In the rush to avoid punishment, three men fell to their deaths. Pigot had the bodies thrown overboard and placed the blame on a dozen other sailors. He had them all lashed.

That night, the resentment from the crew reached a head. Several dozen seamen, led by a surgeon’s mate, stormed the captain’s cabin. Each was desperate to hack at Pigot, who was sliced by a wide variety of knives and swords. Eventually, the bloodied captain was thrown out of his window, alive and screaming. Many of the ship’s other officers faced a similar fate.

The crew realized they wouldn’t be able to return to British territory, so they set sail for ports under Spanish control. They told the authorities there that they had simply set their commanding officers adrift and offered the ship in return for asylum. The Spaniards agreed, and the Hermione became the Santa Cecilia. It was returned to British control just over two years later, when a Royal Navy raiding party landed aboard and killed 100 Spanish sailors.

While the crew adopted new identities, over half of them were eventually captured. Two were caught trying to sail back across the Atlantic in a Spanish vessel, which was intercepted by the Royal Navy near Portugal. In total, 24 of the mutineers were hanged for their actions.

7The Salerno Mutiny

The biggest wartime mutiny in the history of Britain’s armed forces occurred in September 1943. The men were mostly veterans of the 51st Highland Division and the 50th Northumbrian Division who had been injured or became ill in the North African campaign. They had built up a massive sense of loyalty to their divisions and were told they were to be returned to their colleagues in Sicily. Around 1,500 agreed to return to their units, many of them unfit for combat but expecting a chance to rest when they arrive.

Once they boarded the ship, they were told they weren’t actually being returned to their original units at all and were instead being taken to reinforce US troops in the fight for Salerno. They felt betrayed, and when they arrived at Salerno, they found the organization to be farcical. A total of 600 men refused to fight. It later transpired that the order to send them to Salerno had been given in error. Nevertheless, 191 men were found guilty of treason, and three sergeants were sentenced to death. The sentences were eventually suspended, as popular opinion held that the situation had been a grave injustice.

There have been multiple attempts to have the sentences overturned. In 1982, the British government refused to offer a pardon, stating “There are no grounds for doing so which could not be applied to many other mutineers and deserters . . . Nor which would not denigrate the actions of the many millions who fought bravely and obeyed orders at all times.” A Scottish MP has called twice for pardons since 2002, but her pleas have been refused.

6The Revolt Of The Whip

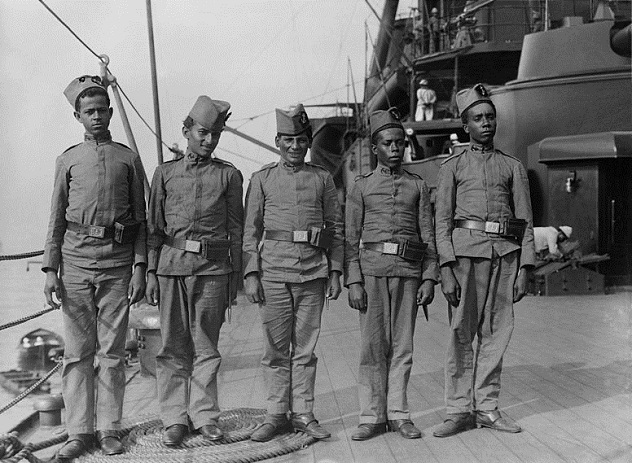

In 1910, the Brazilian warship Minas Geraes was the most powerful in the world. It had been built in the northeast of England, one of the world’s leading shipbuilding regions at the time. The Brazilian navy sent crews to England to learn how to sail the vessel and then to bring it home.

Many of the crewmen were black, and they weren’t treated well. Most were the children of freed slaves or former slaves themselves, as slavery had remained legal in Brazil until 1888. The chibata, or “whip,” was widely employed to enforce discipline. A particularly brutal lashing on November 22, while the ships were moored in Rio de Janeiro’s Ganabara Bay, led to a mutiny that became known as Revolta da Chibata, “The Revolt of the Whip.”

A seaman named Joao Candido led a rebellion that took control of the main battleship. The other vessels in the fleet soon followed. In total, 1,000 sailors were involved in the mutiny. The sailors had relatively simply demands: better working conditions and an end to the use of the whip. The press took to calling Candido “The Black Admiral.” Many in the government, perhaps impressed by the undeniably cool nickname, were sympathetic. Those who weren’t were persuaded by the world’s largest guns pointed directly at Rio de Janeiro.

The crisis lasted five days. The government agreed to the demands and said it would give all of the rebels a full pardon. However, within days, they passed a decree to remove anyone from the navy who was a threat to discipline. Over 1,000 sailors were dismissed. Within a month, Candido himself was thrown into a cell with 17 other people. The conditions were so bad that only he and one other person survived the weekend. The government later put Candido in a mental hospital, but he was released and lived a relatively long life as a fish porter.

5The Columbia Eagle Incident

During the Vietnam War, the US contracted several hundred privately owned ships to deliver supplies across the Pacific. One of these was the SS Columbia Eagle, which left California on February 20, 1970 to deliver 4,500 tons of napalm to Thailand. On March 14, it became the first US ship to be mutinied since 1842.

Two of the crew members walked into the cabin with a revolver they had smuggled aboard. They told the captain and chief mate to plot a course for Cambodia, a neutral territory with no extradition treaty. They then demanded that the rest of the crew leave the ship on life boats. If the crew refused, they threatened to detonate a bomb they had planted and destroy the entire vessel.

The mutineers were Alvinn Glatkowski and Clyde McKay, both in their early twenties. Their motive and plan were both simple and naïve. They were anti-war and hoped that redirecting some napalm would force President Nixon to wind down the war effort. They also hoped to seek refuge in Cambodia. While they were successful in landing there, they did so days before the country’s communist government was overthrown and replaced by one that didn’t have any sympathy for the North Vietnamese cause.

Both of the would-be pirates were thrown in jail, and Cambodian authorities let the ship go. When US officials searched it, they found no bomb, and the napalm was eventually delivered on another vessel. Back in Cambodia, the prisoners were treated reasonably, but Glatkowski didn’t take well to incarceration. By September 6, his mental health had deteriorated to the point that he was eating his own excrement, and he was put in a mental hospital. In December, he was delivered to the US embassy and ended up going back home to serve 10 years in prison.

The fate of McKay is a mystery. His “imprisonment” hardly deserved the word. McKay and a US army deserter named Larry Humphrey were the only two people held on a prison ship, and they had full run of the place. Their guards would take them ashore to go shopping and eat at restaurants. It was during one of these dining experiences that the two men were able to escape their guards and drive away in a stolen car. Neither man was seen alive again. Remains believed to belong to McKay were found in 2001 and returned to the US a few years later.

4The Chilean Naval Mutiny

In 1931, Chile was in financial crisis. In July, the president was ousted from office. Shortly afterward, a caretaker finance minister announced pay cuts for the armed forces of 12–30 percent. On August 31, many Chilean seamen wished to protest the cuts. Alberto Horven, captain of the navy flagship Almirante Latorre, was underwhelmed. He called representatives from all the ships in his squadron, reprimanded them for being unpatriotic, and refused to allow any petitions to be forwarded to the government.

That turned out to be a very bad move. Over the course of the evening, a mutiny was quietly arranged. A crowded boxing match provided ideal cover. In the early hours of the next morning, the officers were awoken by armed intruders, forced to give up their personal weapons, and locked in their cabins. In a little over 12 hours, the entire flotilla was under control of the mutineers.

The revolt spread ashore, and the Chilean government was forced into the unusual position of pitting their army and air force against the navy. The army overran the mutinous naval bases, and the air force performed raids against the ships. Casualties were relatively low, but it was enough to spook the rebels into surrender. They were acting out of practical motives, an attempt to improve their lot—none had any interest in dying for the cause.

3Full Means No. 2

In March 2002, a Taiwanese fishing vessel called Full Means No. 2 was working in the Pacific when it was mutinied by its chef, Lei Shi. The young cook had gotten into an argument with the captain and demanded they return to China. When the captain refused, Shi stabbed him and then attacked the first officer. He threw the captain’s body overboard, but it took 12 hours for the first mate to die. His body was then stored in the ship’s freezer.

Shi holed himself up in the cabin with two large knives and threatened to kill anyone that approached him. He switched off the radio and GPS so the vessel couldn’t be found and ordered the second mate to sail them back to China. He was able to remain in control for two days, but he was eventually overpowered and locked in a cupboard.

Unfortunately, none of the surviving crew were able to figure out how to operate the radio. They set course for the nearest land, which happened to be Hawaii. Full Means No. 2 was intercepted about 100 kilometers (60 mi) from shore. Shi was convicted and sentenced to 36 years in prison by a Hawaiian judge. He appealed on the grounds that the US didn’t have jurisdiction over a craft registered in the Seychelles, when none of the people involved were US citizens, but the appeals court disagreed.

2The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny

Perhaps the largest in history, the mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in 1946 involved over 20,000 sailors across 78 ships and 20 bases on land. It was inspired by a combination of poor conditions, particularly around food, and growing opposition to British rule. It began on February 18 and had reached its full glory within 24 hours, led by a signaler named M.S. Khan.

By the next morning, the naval ensigns on the navy’s ships had been replaced with the Indian tricolor flag. News of the mutiny spread throughout India, and the sailors were welcomed ashore as heroes. Police, students, and workers’ unions went on strike in support. Around 1,200 members of the Royal Indian Air Force marched in favor of the actions. The Brits inevitably panicked.

The Royal Navy were ordered to put down the revolt. Royal Air Force bombers flew low above the Indian ships as a scare tactic. The mutineers were ordered to signal their surrender by raising a black flag. The sheer numbers on both sides made an Indian war of independence entirely possible. However, it wasn’t the British that put down the uprising, but India’s most prominent nationalists.

Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of the National Congress of India, whose flag had been hoisted on the ships. Along with members of India’s Muslim League, he called on the mutineers to surrender. They were disorganized, with no clear goal, and Gandhi really didn’t want a violent resolution. On February 23, the massive rebellion was over as quickly as it had begun.

1The Mutinies Of The Chinese Slave Trade

When the African slave trade began to die off in the middle of the 19th century, a replacement was set up. The shipping of “coolies” was a way of importing cheap laborers, mainly from China, but the way they ended up on ships and the inhumane conditions they were forced to endure during transportation did nothing to differentiate it from the African trade of the last few centuries.

These conditions led to multiple mutinies at sea. In 1860, 1,000 Chinese slaves being imprisoned on an American ship called the Norway staged an uprising. The Chinese laborers started fires in their quarters below decks and broke their way out of the hold. Thirty were shot dead and another 90 were injured before the remainder surrendered. The same year, The New York Times reported that a Chinese slave was shot dead and several others received 100 lashes when they attempted to overtake a ship harbored in Cape Town.

Contemporary reports of the mutinies tended to include tales of cruelty by the Chinese that sound very much like propaganda. An article from 1868 tells of an Italian ship, the Theresa, being mutinied by the 296 people in its “cargo.” While approaching New Zealand, the crew was rushed, a dozen of them being hacked to pieces and thrown overboard. One mate was tortured for 80 days by having nails driven into his head, among other things. Two factions of escaped slaves had a fight that left 50 of them dead. Their heads were stored in the ship’s hold in boxes, and the captain’s wife was forced to endure their stench for 60 days while being “not treated with the greatest kindness.”

Alan would genuinely pay to watch an adaptation of any of these stories at the cinema.