Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Good Things We Owe To The Black Death

Yersinia pestis. Who would think that such a microscopic organism in the gut of an infected flea could create such an upheaval in human society?

The most terrible pestilence humanity has witnessed, the Black Death of the 1340s, killed an estimated 75–200 million people. To many, it seemed that the end of the world had come. In a sense, they were right. The “Great Mortality” ended one world and ushered in a new, better one. Despite the horrors of the bubonic plague, Europe showed remarkable resilience in its survival.

The Black Death, tragic though it was, may have made the world a brighter place. The following improvements to society would undoubtedly have inevitably evolved, but the Black Death was a catalyst. In spearheading change, it allowed humanity to benefit from the new circumstances sooner than later.

10Healthier People

Human populations evolve when confronted with disease. Gene variants help certain people fight infection better than those who do not have those variants. People with these beneficial genes tend to bear more children than those who don’t. This process, known as positive selection, results in favored genes persisting over time while inferior genes die out.

Recent studies have found that descendants of Europeans who survived the plague had their genes altered to make them more resistant to disease. It may explain why Europeans respond differently from other people to certain illnesses and autoimmune disorders. More specifically, a cluster of three immune system genes code proteins that latch onto harmful bacteria, triggering a defensive response. People living in places the Black Death did not ravage lack these toll-like receptor genes.

The Black Death may have been a gigantic laboratory for natural selection to weed out the weak and frail from the population. An analysis of skeletal remains in a London churchyard revealed that people after the plague had a much lower risk of dying at any age than those who lived before. Before the plague, only 10 percent of the population could expect to live past 70; post-plague, that figure had risen to 20 percent. This reshaping of human biology, coupled with the better diets available after the pestilence, allowed post-plague Europeans to be more resilient and thus live longer. As the adage goes, “What doesn’t kill you will make you stronger.”

9The Perfume Industry

During the Black Death, doctors believed, among other things, that poisonous vapors caused the plague. They used aromatic herbs to purify the air. Before the pestilence, humans did have a long history of using perfume, but with the Black Death, the use of personal fumigants truly became the rage.

One of the most popular was orange mixed with dry cloves. People also carried posies of aromatic flowers. Doctors wore nose bags filled with herbs and spices. Pomanders, or so-called “amber apples,” were balls of amber compounded with musk, aloes, camphor, and rosewater, worn around the neck. There was a great demand for aromatic waters such as the concoction of rosemary, lavender, and alcohol known as Eau de la Reine de Hongrie (“the Queen of Hungary’s water”), said to be the forerunner of Eau de Cologne (“water from Cologne”), as well as simpler herbal scents for poorer folk. In the south of France, the area around Montpellier and Grasse became famous as growers of herbs and flowers and as manufacturers of scented waters.

People shunned bathing in the belief that it opened the pores of the body and allowed the foul air in. In the centuries that followed, dousing oneself with perfume to mask body odor took the place of taking a bath. What started as a protective measure against disease gradually evolved into a social custom among the upper classes.

8Hospitals

Before the Black Death, hospitals were simply places where the sick were isolated to not infect others. A critically ill person entering a medieval hospital was a hopeless case. All that the hospital could do was dispose of whatever property the unfortunate wretch had and say a Mass for his soul. In fact, these hospitals took more care of one’s soul than one’s body since disease and sickness were regarded as punishments for sin. Indeed, hospitals were religious institutions where the patient’s treatment regimen were confession and prayer. The Mass was the central aspect of hospital life.

Medieval hospitals had no professional doctors or nurses and were staffed by monks and nuns. Though practiced, curing the sick was not high on the agenda and largely consisted of herbal concoctions. Hospitals also functioned as almshouses and pensionaries, taking in widows, orphans, guests, and travelers. The word “hospitality” shares the same Latin root as “hospital.”

The great pestilence jump-started the transformation of the hospital from a charity endeavor to a place where the sick go for treatment. With so many stricken by the disease, hospitals were forced to give up their multiple functions as way stations and hospices so that they could concentrate on the sick and dying.

Simultaneously, there were important changes in medical practice. The failure of traditional medicine to arrest the plague was analyzed and discussed, and new ideas were put forward. Medicine ceased to be theoretical and text-bound and became more observational and practical. Anatomy and surgery became parts of the medical program in universities. From being a quaint philosophy, medicine evolved into a practical physical science.

With professional doctors becoming more central to a hospital’s operations, medical services were specialized, and there arose hospitals or wards devoted to different categories of illnesses.

7Sex Comedies

In the Middle Ages, religious authorities condemned all secular entertainment as the devil’s work. But many began to take notice of the therapeutic powers of laughter (the Bible itself says that “a merry heart doeth good like a medicine”). Defenders of non-religious literature argued that a good Christian needed respite from hard spiritual struggle, and comedy, in particular, could help a patient recharge.

The plague further strengthened this view. Tracts disseminated during the pestilence gave the following prescription: “Whoever wishes to keep himself healthy and fight against death from pestilence should flee anger and sadness, leave the place where sickness exists, and associate with cheerful companions.” Physicians quite literally believed that laughter could cure disease.

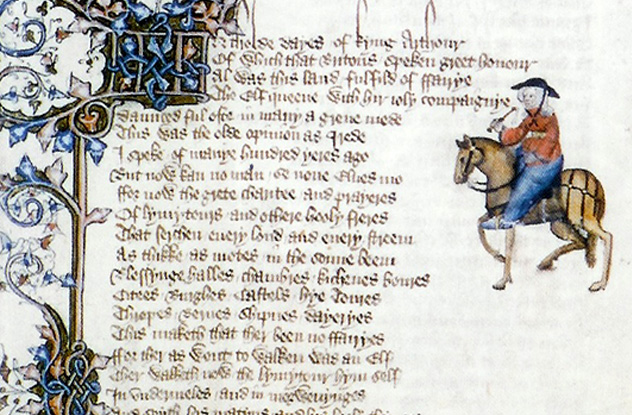

The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, perhaps the first work of literature as entertainment in Europe, was a comedy. Written in 1352, it consists of 100 stories of love and other misadventures told by a group of ladies and gentlemen hiding from the Black Death. To make his work appeal to all classes, Boccaccio unabashedly used sexual humor as a dominant theme. Since sex and religion were the two things people at the time readily understood, The Decameron weaves religion and sex into its bawdy tales. Sex is implied rather than explicit so as not to offend more conservative members of society. One story, for example, tells of a monk who seduces a beautiful girl by telling her that she could better please God by letting him put his “devil” into her “hell.”

Modern fiction as a genre was born with the Decameron. It was the first to tell stories about common people in real-life situations. Geoffrey Chaucer used it as inspiration for The Canterbury Tales. Just how revolutionary this genre was at the time can be seen in Chaucer’s apology for any offense he might have caused with his tales, explaining that he must be faithful in recording his characters’ words, no matter how rude or disgusting. In the 20th century, the Decameron influenced James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway.

6More Functional Homes

The dearth of skilled artisans and builders after the plague forced architects to strive for simpler building designs. English churches, for example, moved away from the flamboyant Decorated Gothic to the less ostentatious Perpendicular Gothic style, so-called because of its emphasis on vertical lines. The new style allowed for more immense windows, giving stained-glass craftsmen greater scope for creativity.

There was also an increased demand for private spaces in domestic architecture, perhaps a reaction to the pre-plague crowding that had enabled the disease to spread rapidly. House plans in the pre-plague world consisted of a hall, which was a single room open to the roof timbers with an open hearth. Here, the family lived communally and received guests. Poorer folks lived in timber houses with wattle and daub panels and thatched roofs that offered little protection from rats and other vermin.

By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the hall was divided by partition walls on one or both ends. This separated the occupants from servants, animals, and the dirt of the streets. Sometimes, these end sections were further divided into a lower chamber or parlor and an upper solarium. At Bodiam Castle, private rooms even had their own latrines. The use of rushes to cover the floor, which were breeding grounds for vermin, was abandoned in favor of carpets and rugs. Private homes became more luxurious and comfortable.

5Predominance Of English

You’re reading this article in English rather than in Latin because of the Black Death.

Literacy made a tremendous jump after the plague. With the deaths of almost all the literate monks who copied manuscripts by hand, Europeans felt the need for a better way to copy books. This provided an incentive for the invention of the printing press. Soon, Europe was awash with books. The Renaissance equivalent of the Information Age had arrived, leading to the Scientific Age in the next centuries.

Among those seeking higher education, the fear of long journeys and being exposed to plague provided a reason for establishing local universities. The number of universities saw a marked increase after the plague. Many professors who spoke Latin had been wiped out, so teachers fluent in this language of higher education were brought up from lower schools to staff these new universities. Consequently, the lower school vacancies were filled up by teachers who had little or no working knowledge of Latin. Instead, they used the vernacular, and the years after the Black Death saw greater use of the vernacular languages. Boccaccio wrote the Decameron in his native Italian, allowing more people to appreciate his prose. Medical and other practical texts were now accessible to many.

The formerly servile middle class, now in power, also knew no Latin. The decline of Latin in England climaxed in 1362, when English was declared the official language of the courts. By 1385, English was the language of instruction in schools. When Britain girdled the world with her empire, English followed and is now the lingua franca of modern society.

4End Of Feudalism

Feudalism describes the system by which a vassal owed a lord homage, fealty, and loyalty in exchange for the use of his land. Medieval society was thus stratified into three distinct classes: those who prayed (clergy), those who fought (nobles and knights), and those who labored (serfs). This lowest class was always prey for exploitation by powerful landowners.

The feudal system that burdened peasants with obligations to their lords was turned upside down by the Black Death. So many peasants died during the plague that fields lay abandoned, and the crops went unharvested. Lords became desperate for workers. Taking advantage of the scarcity of labor, surviving peasants demanded higher wages—in cash rather than in kind—and fairer treatment for their services. For the first time, they dictated the conditions for their labor. Serfdom had found the source of its power against the nobility.

The great lords did not take the serfs’ newfound bargaining power lying down. Over the next several years after the Black Death, the king and the nobility passed laws that tried to bring back the pre-plague status quo. In 1350, the Statute of Laborers was enforced in England, seeking to “prevent laborers from obtaining higher wages.” The unfortunate law, together with the Poll Tax of 1381, provoked the Peasants’ Revolt.

But not even the king had the power to undo the dramatic changes to the structure of medieval society. Gone forever was the tripartite division of humanity. The new freedom of the laboring class created more job opportunities and more social mobility. The former serfs were now working for themselves, not for their lord. Here was the faint glimmering of the individualism so treasured in our modern Western society.

3The Middle Class

Freedom from feudal obligations gave many peasants a glimpse of wider horizons beyond their village. More ambitious peasants were lit with a sense of purpose and flocked into cities to engage in crafts and trades. The more successful ones became wealthy. They became a new middle class. Cities became a hive of activity as the economy, now firmly on a cash basis, took off. Competition among individual manufacturers slowly replaced the guilds, which hitherto dictated rules of production and the cost of goods. The roots of the capitalist system had emerged.

With more disposable income, the new rich could afford more of the luxuries obtained in the East. The traffic between East and West stimulated trade and an increase in merchants and traders. Eastern ideas, especially from the Muslim world, flowed into Europe, stimulating a rise in learning. Townspeople became so affluent that they rivaled the old landowning nobility. The gentry didn’t like the competition, and in a Sumptuary Law passed in 1363, they forbade merchants and their families from wearing cloths of gold, silver, or silk and from adorning themselves with jewels or fur.

Aside from investing in personal luxuries, the middle class used their wealth to become patrons of the arts, science, literature, and philosophy. The result was an explosion of cultural and intellectual creativity we now call the Renaissance.

2Freedom of Thought

The Christian faith ruled all aspects of medieval life, from womb to tomb. But the stranglehold the Catholic Church exercised over people’s lives and ways of thinking was broken by the Black Death.

Whatever rudimentary knowledge of medicine existed had been employed in the context of theology and spirituality. But with clergy and monks dying with the common folk, and with no answers as to why the horror was happening, the Church revealed itself clueless in the face of catastrophe and thereby lost credibility as an exclusive pipeline to God. As a result, many people lost faith or turned to other paths of spirituality. Dogma was increasingly questioned, and people began to think for themselves.

The first manifestation of common people bypassing the priesthood to search for their own path to God was the phenomenon of the Flagellants. These people roamed Europe, flogging themselves in the belief that personal physical suffering could atone for their sins. The alienation from the Church also affected the more intellectual, and in England, John Wycliffe began to express dissent and rebellion against Church dogma and abuses. This would lead, 200 years later, to Martin Luther’s eventual break with Rome and the start of the Reformation. The floodgates of freethinking opened, and in the next centuries, even the existence of God began to be doubted, leading to the Enlightenment.

1Humanism

The appalling death toll made the survivors of the Black Death ponder the individual’s worth. The questioning of faith in the face of the plague’s terrors led people to focus more on the present life with its wonders and beauty, rather than the promise of a next life. This led to an appreciation of the arts and physical sciences and a thirst for human-based knowledge. Human endeavor and accomplishments, rather than religion, took center stage in this humanist movement.

Petrarch (1304–1374) proclaimed a new anthropology that saw humans as rational and sentient beings, intrinsically good and capable of thinking for themselves. It rejected the Christian doctrine of the Fall of Man and the resulting Original Sin. Instead of human abnegation, it stressed human dignity.

The Church’s traditional explanation of man’s role in the universe was turned upside down. No longer was the ideal life of penance but rather a life dedicated to recovering the lost human spirit and wisdom. Reason and logic became more important than faith. Individuals were encouraged to realize their potential through a liberal arts education. The possibilities of human creativity seemed endless and exciting.

The new urban middle class helped in the spread of humanism. These rich businessmen inevitably acquired political power, and in doing so, they looked back to classical Greece and Rome as working models for their governance. Interest in the literature and arts of antiquity followed. Artists and authors, encouraged by their patrons, deliberately turned their backs on traditional medieval styles and created a new culture. It was a rebirth—a Renaissance that laid the groundwork for our modern secular society.

Larry is a freelance writer whose main interests are history and chess.