Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

10 Bizarrely Noteworthy Medical Milestones Throughout History

The history of medicine has not unfurled gradually. Instead, it is made up of moments—points in time when someone did something really important that would go on to have a significant impact on the medical world as a whole. Each subsequent moment brings us closer to the inevitable conclusion where we all become immortal cyborgs, but until that day, we can look back on some of the noteworthy moments from our past.

10Charles-Francois Felix Removes The Sun King’s Anal Fistula

The year is 1686, and the king has a pain in the butt. Specifically, we are talking about Louis XIV, king of France. Despite enjoying a very lengthy reign of 72 years (also earning the moniker “the Sun King”), Louis was not a healthy man. He suffered from headaches, gout, periostitis, and (some also suspect) diabetes. And in 1686, the king was stricken with a very painful anal fistula that would not go away despite all the enemas and poultices that were the accepted practice at the time.

Perhaps in an act of desperation, the king did something unusual for that time—he turned to a barber-surgeon. Back then, physicians considered surgery beneath them, so the practice was usually left to barbers since they were skilled with a blade. The barber in question was named Charles-Francois Felix. He received around six months to prepare and was told to come up with a procedure to ease the king’s suffering. After practicing on 75 alleged volunteers from France’s prisons, Felix perfected two instruments with which to perform the surgery—a spreader and a scraper.

The procedure went well, and King Louis showered Felix with wealth and titles. All of a sudden, having an anal fistula became the latest trend in France, and many courtiers approached Felix, demanding the royal surgery to imitate the king. But on a more serious note, this also helped legitimize surgery, and physicians started looking at it as a viable alternative.

9Ambroise Pare Runs Out Of Oil

One of the most famous barber-surgeons in history was Ambroise Pare. During the 16th century, he served four different French kings, and before that, he was a pioneer of battlefield medicine. During that time, the pain suffered by a patient wasn’t of paramount concern to medical professionals. It was more of a “you either live or you die” scenario. Pain was expected with most medical procedures, and it wasn’t uncommon for it to be so excruciating that patients would pass out in the middle of the operation.

One of the most painful but essential procedures was cauterization. The surgeon would use boiling oil to seal gunshot wounds. Even so, the chances of the patient surviving the ordeal were slim. In 1536, during the Italian War, Pare was serving as a war surgeon. One day, he ran out of boiling oil to treat injured soldiers, so he created a tincture using rose oil, egg yolks, and turpentine. He didn’t expect it to do much good. To his surprise, the next day, the soldiers treated with his new recipe were in much better shape.

Pare showed the world there were less agonizing alternatives to cauterization and continued his trend by also popularizing the use of ligatures after amputations. Furthermore, Pare brought attention to his ideas through a very simple yet unconventional method—he wrote in French instead of Latin. That way, all the less educated barber-surgeons would be able to learn what he had to say.

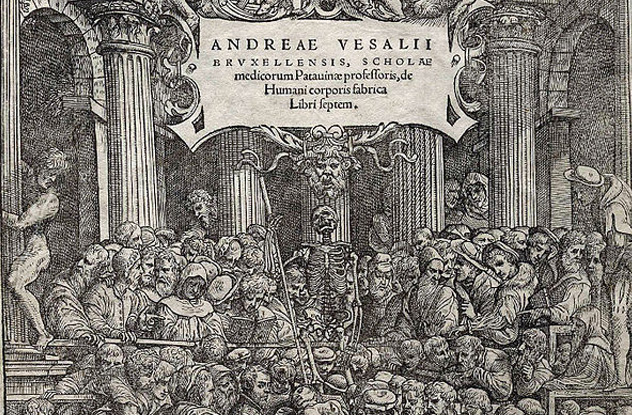

8Andreas Vesalius’s Dissections

Claudius Galenus (or simply Galen) was one of the most important scientists of ancient Greece. Primarily a physician and surgeon, Galen’s medical accomplishments are almost on par with those of Hippocrates. He became renowned for his insight into the inner workings of the human body, which he gained primarily through dissections on animals. However, we are still talking about the second century here, so Galen got a lot of stuff wrong.

The man was so respected that his notions remained mostly unchallenged for centuries. It wasn’t until the 16th century that Galen’s teachings were challenged by another publication by Dutch anatomist Andreas Vesalius. In 1543, Vesalius wrote On the Fabric of the Human Body, which showed conclusively that Galen was wrong on several points regarding the human anatomy. More than that, Vesalius based all of his observations on his own personal human dissections, so he also urged doctors to take a hands-on approach to medicine.

Fortunately, Vesalius also had some powerful supporters (like Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire), which ensured that his book became one of the most important anatomy publications of all time. Like Pare, Vesalius wanted to ensure that his book was as accessible as possible, which is why it contained over 200 high-quality illustrations by skilled artists who were clearly present during the dissections.

7Ephraim McDowell Performs The First Ovariotomy

American physician Ephraim McDowell earned worldwide renown for one particular case—or two cases, if we’re counting the time he removed bladder stones from a 17-year-old James Polk, future president of the United States.

On December 13, 1809, McDowell went to see Jane Todd Crawford, a woman who was thought to be pregnant beyond term by her local doctor. After McDowell inspected her, he promptly diagnosed Mrs. Crawford with a giant ovarian tumor. He explained to her that nobody had ever tried to remove such a tumor and that most doctors would consider the procedure impossible.

Even so, Mrs. Crawford had nothing to lose at that point, so she let McDowell operate on her. She had to endure a 25-minute procedure without anesthesia, during which the doctor removed a 10-kilogram (22 lb) tumor. Despite the grim prognosis, Mrs. Crawford recovered fully in less than a month and lived for 32 more years. McDowell went on to become known as the “father of the ovariotomy,” although not immediately since he waited for eight more years before writing about the procedure.

6Richard Lower Performs The First Blood Transfusion

Blood transfusions are an essential part of modern medicine, but there was a time when they were mocked. Obviously, blood has played a role in many rituals throughout history, but it wasn’t until the middle of the 17th century in London that transfusions were studied as a possible medical treatment. The man behind the research was Richard Lower, an Oxford physician and member of the Royal Society, which had only formed a few years prior.

In 1665, Lower performed the first successful animal transfusion. He took blood from one dog and put it in another dog. That done, he moved on to people. In 1667, a sheep served as the donor, while a volunteer named Arthur Coga became the first human recipient of a blood transfusion and was paid 20 shillings for his services. Noted diarist Samuel Pepys was present at Coga’s medical procedure and took extensive notes.

Coga received 9–10 ounces of sheep’s blood, and the landmark procedure was published in Philosophical Transactions. However, the public didn’t regard this event as anything noteworthy. Quite the opposite, in fact. Lower and the Royal Society were mocked and branded as mad scientists. A play called The Virtuoso written by Thomas Shadwell even satirized the sheep-to-human transfusion.

Coga was a little mad, and Lower incorrectly thought the blood transfusion would fix his mental problems. When that didn’t happen, people dismissed the idea, and it would take a century before blood transfusions would seriously be considered again.

5Dominique Jean Larrey Perfects Battlefield Medicine

Dominique Jean Larrey is often regarded as the first modern military surgeon because of his many innovations in the field that are still relevant today. It didn’t take long for Larrey to learn all the standard practices of the time and enroll as a military surgeon under Napoleon. After that, he pretty much decided that all of those practices were wrong. For example, it was standard for hospitals to be kept miles away from the battlefield for safety. While this made them safe, it also made them empty, as many injured soldiers died en route. Larrey decided that battlefield medicine would be much more effective in medical tents erected near the front lines.

Now that the hospitals were closer, Larrey also wanted the method of transportation to be faster. That idea gave birth to the flying ambulance, the first army ambulance corps. They were horse-drawn carriages, typically used to maneuver artillery. Larrey also became an expert on amputations, developing techniques to make the procedure faster and safer. Supposedly, he once performed 200 amputations within 24 hours.

Larrey’s dedication earned him the admiration of Napoleon (who first named him surgeon-in-chief of the French army and later a baron), but he was also idolized by the soldiers. After the devastating defeat at the Battle of Borodino, Larrey was picked up and passed around crowdsurfing-style by soldiers who wanted to make sure he didn’t get trampled while retreating. Even Napoleon’s most bitter enemy, the Duke of Wellington, gave orders to his men not to shoot on Larrey’s tent at Waterloo.

4Sushruta’s Rhinoplasty

Ancient India excelled in many scientific fields such as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. While the Western medical world had men like Hippocrates and Galen, India had Sushruta. An ancient surgeon active during the sixth and fifth centuries BC, Sushruta is sometimes called the “father of plastic surgery” for his teachings on nasal reconstructions. He gave quite a detailed description on how to perform a primitive form of rhinoplasty by removing skin from the cheek flap and attaching it to the nose. We can’t say for sure if Sushruta ever actually successfully attempted this procedure, but the level of detail is still quite remarkable for the time period.

Plastic surgery aside, Sushruta’s other notable contribution to medicine was the Sushruta Samhita, an ancient text that became one of the foundations of Ayurveda, the traditional Indian medicine that’s still used today. The compendium contained most, if not all, of the medical knowledge India had at the time. It covered over 1,000 illnesses and hundreds of plants, minerals, and animal preparations that supposedly had healing capabilities.

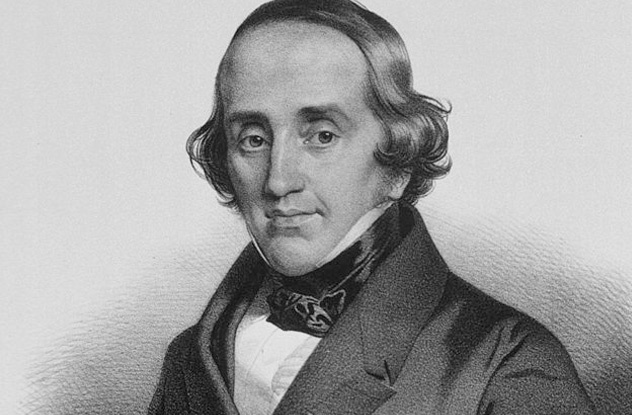

3Jean Civiale Performs The First Minimally Invasive Surgery

Passing a kidney stone is often claimed as one of the most painful experiences you can endure, with certain women even putting it one step above the pain of child labor. Over one million people have to deal with a kidney stone every year in America alone. Thankfully, we don’t do it the old-fashioned way anymore. Nowadays, we use a minimally invasive procedure called a lithotripsy, which uses various techniques to crush the stones.

Before the 19th century, the standard procedure was a lithotomy. It involved making an incision and removing the stone whole. Not only was it extremely painful, but it also carried a high mortality rate. But in came French physician Jean Civiale with his invention, the lithotrite, which he used to perform the first minimally invasive surgery in the world. With this tool, Civiale was able to crush the stone before removing it through the urethra.

Civiale, a pioneer of urology and the founder of the first urology center in the world at Necker Hospital in Paris, showed that his method was much more efficient than a lithotomy. While the traditional technique had a mortality rate of over 18 percent, his lithotripsy hovered around the 2-percent mark. He did this through an ample and comprehensive study commissioned by the Paris Academy of Science, a significant feat of evidence-based medicine that was highly influential for the time.

2George Hayward Performs First Amputation Under General Anesthesia

Very soon after William Morton introduced ether as anesthesia in 1846 with his “Letheon” inhaler, physicians were already thinking of the possible applications it might have. Sure, the gas proved itself potent enough during a minor surgical procedure, but could it be used for major surgery as well?

The process was somewhat delayed by Morton’s reluctance to reveal ether as the core ingredient of his inhaler. Doctors wanted to use his concoction but were wary of using an unknown agent on their patients due to potential side effects. Morton offered to supply Boston hospitals with Letheon free of charge, but physicians took a stand and demanded to know the formula used with the inhaler. At this point, Morton finally conceded and admitted to using sulfuric ether.

Now that that issue was out of the way, the anesthesia could be used on a much more ambitious medical procedure—an amputation. The task was undertaken by Dr. George Hayward. The patient was a 21-year-old servant girl named Alice Mohan whose leg needed to be amputated due to tuberculosis. Like before, Morton administered the gas until the patient fell asleep. Hayward tested her reaction by stabbing Alice with a pin. When she didn’t react, he quickly proceeded to cut off her leg.

Alice later awoke, not realizing that she’d fallen asleep and that the procedure was finished. When she said she was ready to begin, Hayward reached down and picked up her leg from sawdust and presented it to its former owner.

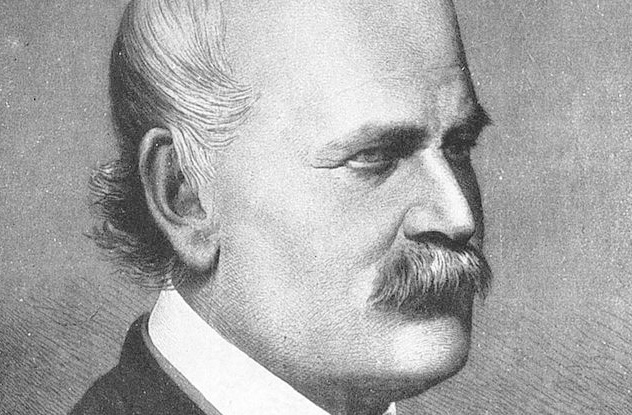

1Ignaz Semmelweis Tells Doctors To Wash Their Hands

Humans can be very slow to change when a new notion goes against long-held beliefs. Richard Lower was mocked for his work on blood transfusions. When Edward Jenner came up with the smallpox vaccine, he was criticized by the clergy for his ungodly work. And yet probably no man has made a greater contribution to medicine that earned him nothing but scorn and mockery than Ignaz Semmelweis.

Nowadays, the man is known as the “savior of mothers” and you don’t get that kind of moniker unless you did something right. We also know that infection is a serious problem, and doctors go to great lengths to ensure that they operate under sanitary conditions. This wasn’t always the case, though.

Joseph Lister usually gets the credit for pioneering antiseptic surgery, but Dr. Semmelweis had the same idea several decades prior. The only difference between them was that Semmelweis became a pariah of the medical world for his ideas.

Semmelweis realized that there was a direct correlation between infection and puerperal fever in obstetrical clinics. Just by washing their hands and their instruments, doctors could drastically lower the mortality rates caused by the fever to below 1 percent. Puerperal fever was a common problem in the 19th century and had a mortality rate of up to 18 percent. However, doctors simply refused to believe that they could be responsible for so many deaths. It wasn’t until Pasteur proved germ theory that people finally realized Semmelweis’s ideas had some merit. By then, Semmelweis went insane trying to convince others and was committed to an asylum, where he was beaten to death by guards.

Follow Radu on Twitter.