History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Legendary Exploits Of The Pinkerton Detective Agency

The Pinkerton Detective Agency conjures up all kinds of images—the hard-boiled private eye, the undercover detective, the labor enforcer. The agency has had an extremely torrid history, with all sorts of things happening through the decades. Some of the stories of the Pinkerton detectives are the stuff of crime novels.

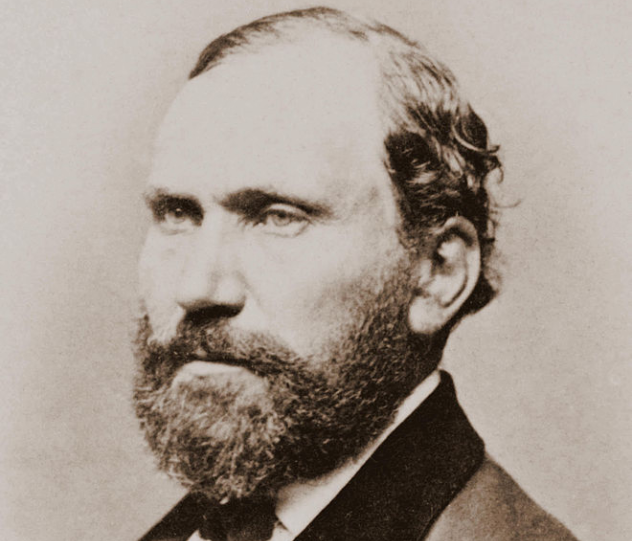

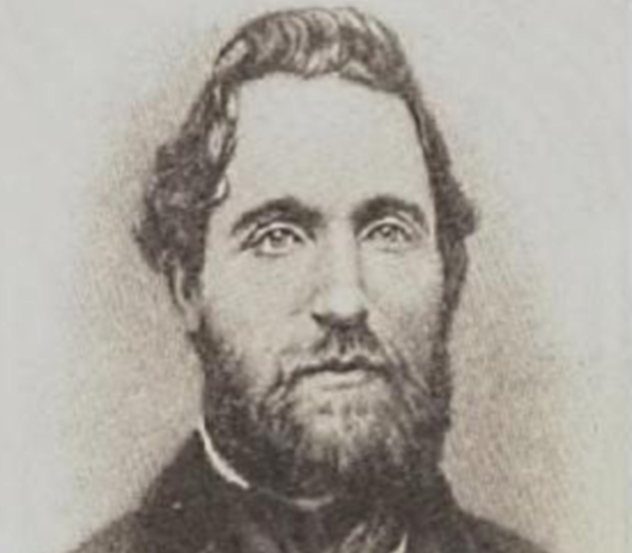

10 Allan Pinkerton’s Accidental Introduction

The man at the head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency might have been known as one of America’s great lawmen, but he was also a Scottish immigrant. Born in Glasgow in 1819, Allan Pinkerton and his wife were forced to leave Scotland when he took a stand with some pretty radical pro-labor ideas. He came to the US in 1842, and they settled in Chicago, where he set up shop as a barrel-maker.

His introduction to the world of crime fighting was about as accidental as you can get. He was gathering wood for his barrels one day when he stumbled across a camp in the woods. It belonged to counterfeiters, who were making coins. Being the law-abiding citizen that he was, he turned them in. After helping with the arrests, he was made a deputy sheriff of Kane County, and he ended up being so good at it that he was soon the first man to be employed as a full-time detective in Chicago, as well as a special agent working for the post office.

By 1850, he left his appointments and created Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. He used the motto, “We Never Sleep,” and the logo of an eye—leading to the phrase “private eyes.” Within the first 20 years of operation, they had already amassed the largest collection of mug shots and criminal records of any agency in the world, and with 2,000 regular employees and 30,000 reserve agents, their force was larger than any single standing army in the US at the time.

9 The Homestead Works Failure

The agency certainly wasn’t without its failures, though, and the Homestead Works incident would long be a sore spot.

In 1892, Andrew Carnegie headed to Scotland, leaving an already unruly business empire in the hands of his partner, Henry Clay Frick. Unions were clamoring for better wages and an active role in business, while the men at the head of those businesses were struggling to maintain some kind of control. One of Frick’s biggest problems was Pennsylvania’s Homestead Mill, and things went sideways very, very quickly when he closed the mill and kicked out about 3,800 workers. Those workers quickly took the mill back and went on strike. The Pinkertons were called in to protect the strikebreakers, but they found themselves facing off against the whole town.

The townspeople had cannons.

The Pinkertons, arriving by barge, were trapped on the water as workers barricaded shores, and 5,000 curious spectators came in from nearby Pittsburgh to watch the showdown. Townspeople emptied stores of ammunition and, during the 12-hour war of attrition, shot the Pinkerton surrender flag out of the air four times. According to one of the men trapped on the barge, “We were penned in like rats and we went at the fighting like desperate wild men . . . All of our men were under the beds and bunks, crying and trembling.”

Surprisingly, only 10 people were dead by the time the mill workers accepted a surrender and allowed the Pinkerton barges to land. The Pinkerton men were then beaten bloody and senseless by men and women alike, jailed for their own protection, and put on a train out of town the next day.

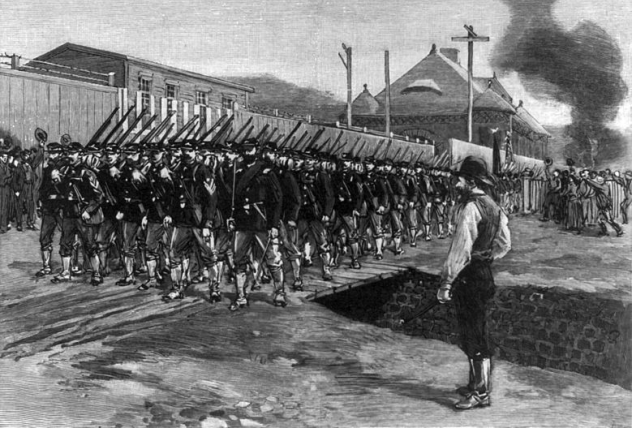

It took all 8,500 members of Pennsylvania’s National Guard to put down the rebellion, secure the mill, and get it running with 1,700 strikebreakers. Townsfolk who had originally greeted the arrival of the troops with a brass band realized very quickly that they were being put under martial law. The gunfire continued to the point where basic facilities for the scab workers needed to be built on mill grounds, because they weren’t able to get into town without causing riots.

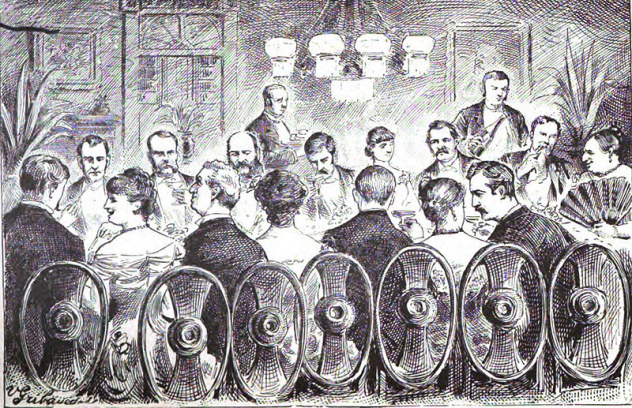

8 Bringing Down Marm Mandelbaum

In the late 19th century, Marm Mandelbaum was at the head of one of the most notorious crime rings in New York City. A Prussian immigrant, she began by recruiting child pickpockets, and she quickly escalated to dealing in all sorts of stolen goods. She had layers and layers of protection, from crooked cops to Tammany Hall politicians who recognized her power and figured that her influence was a sure way to win votes. She had lawyers on retainer should any of her thieves run into trouble, a group of cab drivers on call, and a network of associates that were credited with putting the US on the map as far as crime syndicates went.

When the district attorney decided it was high time to take her empire down, there was a problem. She had gotten as far as she did by being smart and being cautious, and one of her cardinal rules was not to deal with anyone she didn’t know. No one knew just how many cops were on her payroll, either, but the DA did know that word of any sting operation would make its way back to her.

Enter the Pinkertons, specifically, a Pinkerton agent named Gustave Frank. Frank spent five months getting into the door of her syndicate, posing as a dealer in one of her favorite commodities—silk. He passed all her tests, cutting off and “disposing of” identifying marks on bolts of silk, all the while asking for an in with her, looking to buy stolen silk. After weeks of research and months of surveillance, he not only started buying stolen silk from her, but he also confessed to be not just a merchant but a lifelong criminal. Eventually, he bought more than 11,000 meters (36,000 ft) of stolen silk worth thousands of dollars, while tracing the silk back to those it had been stolen from by the same identifying marks that he had already shown a willingness to get rid of.

Mandelbaum jumped bail and fled to Ontario, spending the rest of her life in exile.

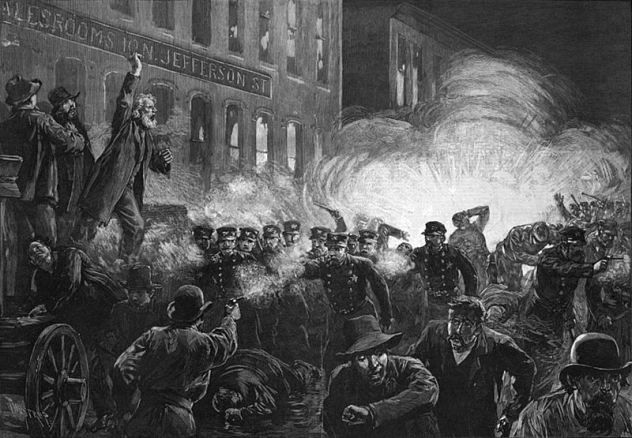

7 Haymarket Affair Accusations

In 1886, tensions at the McCormick Reaper Works factory in Chicago came to a head when six workers were killed after a conflict with armed police officers. Needless to say, that did nothing to alleviate the already strained fears of further conflict between workers, laborers, and immigrants. When a bomb was thrown during a public rally held the next day, it led to more worker deaths and the arrest of eight demonstrators. Even though it was widely known and accepted that none of the men arrested were the ones responsible for the bomb, four were hanged, one committed suicide in jail, and three were sentenced to prison (and pardoned in 1893). No one has ever been positively linked with the bomb, but there was a surprising suspect—the Pinkertons who had been called in to help settle the dispute.

When the eight men were put on trial and took the opportunity to speak for themselves, they made their opinions on the Pinkertons very clear. Claiming that the agency offered a “secret circular” and provided their services in the support of capitalism and the rich, the men accused them of supporting monopolies and doing whatever they needed to in order to stir up more trouble. Accusations were thrown about that those who were putting down the strike threw the bomb to make the masses of protesting workers out to be animals. Evidence was given in the form of articles written by the New York Tribune and the New York Times, seeming to suggest that drastic measures like the bomb were the only way to break the strike and show clearly just who was in charge.

Far from heroic lawmen, the Pinkertons were allegedly becoming agents of the rich and powerful, although there’s no real evidence to suggest, one way or the other, whether or not the accusations had any basis in fact.

6 Henry Julian And Frederick Ker

In the early 1880s, Frederick Ker was in some pretty serious legal trouble for running an embezzlement scheme that involved speculating on his company stocks with company money. Smoothing things over with his bosses, he went on a supposed vacation to New Orleans and, instead of returning, his employers got a notice that he had stolen $21,000 in cash and $35,000 in bonds. Ker headed to Lima, Peru, and a Pinkerton agent named Henry Julian was dispatched to bring him back. That’s where things got a little hazy.

The United States and Peru had a treaty in which criminals would be extradited, and embezzlement was one of the crimes that was covered in the treaty. Julian was given all of the proper extradition papers, but US authorities never notified the Peruvian government that Ker was in their country or that Julian was going to get him. When Julian got there, he didn’t execute the extradition papers, either, even though he carried them, and they were all signed and sealed.

Julian tracked him through Panama and to Peru, where he ended up recognizing the man but not arresting him right away. Instead, he struck up a conversation and befriended Ker, and things got even more hazy. While waiting for the paperwork and extradition order to arrive, the two men started hanging out together. When the order did arrive, it was addressed to the Peruvian government and specified larceny as the crime. The problem was that the Peruvian government had been ousted by Chile, and in lieu of following more proper channels to sort out the mess, Julian grabbed Ker, put him on the US Navy’s warship Essex, and headed home.

While Ker didn’t deny his crimes, he did attempt to sue based on how he’d been brought back to the United States. Not thinking that it was fair that he had been abducted and held on the warship, he claimed that he had been illegally arrested, kidnapped, and detained, all without due process.

The case was Ker vs. Illinois, and the ruling was rather epic. While Ker claimed all sorts of legal procedures had been dodged by the Pinkerton agent, the court ruled first that the whole thing was a kidnapping case and not an extradition case. As Julian had skipped the whole extradition part and just kidnapped him, none of his other complaints about due process even applied to the situation. As far as the court was concerned, they didn’t care about how Ker made it back to Illinois, just that he showed up on their doorstep in handcuffs.

The court did, however, suggest that if he was really that upset about the whole thing, he could have Julian extradited to Peru and take it up with them.

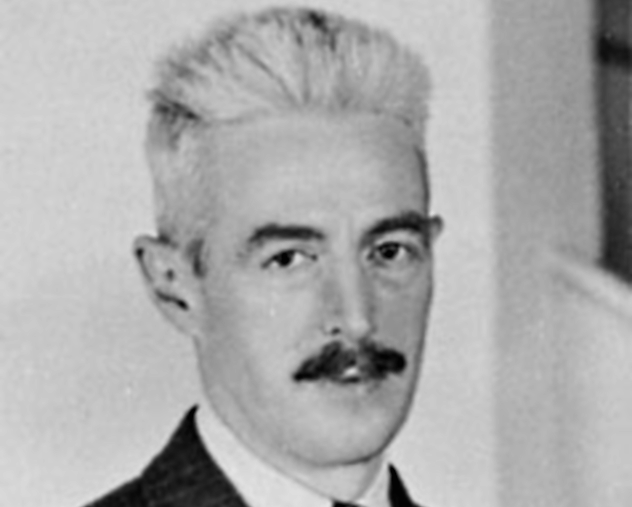

5 Dashiell Hammett

Hammett is known for his detective stories, to say the least. He most famously wrote The Maltese Falcon, along with The Dain Curse, The Thin Man, Red Harvest, and The Glass Key. He was massively lauded in the 1930s, fell into obscurity during the following decades, and died in 1961.

He was also a Pinkerton, and he got a lot of his practical experience while he was on the job. When he was 14, he was working as a messenger on the B&O Railroad, and after that, he moved on to the Pinkertons. Training on the job under one of the Pinkerton’s established detectives, he was out in the field by 1917.

Everyone has those moments where suddenly, the ways of the world all become clear, and they realize just what kind of world they’re living in. Hammett had his moment in Montana, where he had been tasked with helping to break a strike by a group of copper miners. When he got there, he found it wasn’t as clear as he might have thought, starting with when he and his colleagues were offered $5,000 to kill the lead organizer of the miners, a man named Frank Little.

Hammett refused, but Little died anyway, meeting his end at the end of a rope dangling from a train trestle. Hammett never knew whether or not his associates had anything to do with the murder, and he never knew if they had taken the money or not, but suddenly the world was painted in a whole new set of shadows and shades of grey.

The other high-profile case that he worked on was also by no means a simple one—the accusations of rape and murder that had been filed against actor Fatty Arbuckle.

Later, he would write Red Harvest based on his experiences in Montana, and those experiences would continue to influence his writing, which would, in turn, change the game for detective novels.

4 John Scobell And Timothy Webster

After aiding in the foiling of an assassination attempt on Abraham Lincoln, Allan Pinkerton continued to aid in the Civil War effort, and the work of his spies was invaluable. Not only was he the first to hire female detectives, but he also saw the benefits in hiring freed slaves to head back down to the Confederate states and start gathering intelligence.

John Scobell was one of Pinkerton’s most successful agents. A former slave, he had been well educated before being freed. Recruited in 1861, he went on a series of missions posing as a variety of different people, from servants and cooks to laborers. Sometimes, he would work with other Pinkerton agents; sometimes, he would head out on his own and ingratiate himself into different communities to gain intelligence that would have been otherwise inaccessible.

Scobell joined British-born Pinkerton spy Timothy Webster (pictured above) on a mission into Baltimore. Tasked with getting in good with the Confederate intelligence officers, Webster ultimately worked his way into Confederate intelligence’s good graces so much so that he was given a free pass to travel anywhere in the South that he needed to go.

Laid up with inflammatory rheumatism and in the company of Scobell and another Pinkerton agent, Webster’s cover was blown when more Pinkerton men started asking questions about him and were recognized. Webster was arrested and ultimately hanged, though Scobell was released under the assumption that there was no way a slave could be acting as a spy.

Webster was executed in 1862, and it wasn’t until the next year that Robert E. Lee would write that the greatest source of intelligence information received by the North was coming through slaves and former slaves. Meanwhile, Scobell was at the center of several successful missions, earning praise from Pinkerton, who called him a “cool-headed, vigilant detective.”

3 James McParland And The Molly Maguires

Coal mining has always been a brutal occupation, and in the 1870s, it was especially so. Unfair practices by mine owners led to the organization of not just unions, but of the Molly Maguires, an incredibly violent, Robin Hood–like group who stood up to the mine owners for the rights of the workers and did so in extreme and unpredictable ways. The mines, haunted by the presence of the incredibly secretive group, were owned by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which hired the Pinkertons to bring the Irish gang to justice for sabotage and murder.

Bringing them to justice for their crimes meant getting a man on the inside, and that man was James McParland. Pinkerton needed a particular sort: He needed a hard-drinking Irish tough who was able to hold his own among the miners and also to turn on his countrymen. McParland was his man, and he went undercover as con man and murderer-on-the-run James McKenna.

Getting his foot in the door was the hard part, and it happened a few weeks after he started hanging out in the same bar as the Mollies. Accused of cheating at a card game, McParland went toe-to-toe with one of the biggest Mollies on the block, knocking him out and creating an instant name for himself. It wasn’t long before he was completely accepted, not just as a member but a secretary of one of the Mollies’ main divisions. His position allowed him to travel throughout the district, gathering evidence all the while.

McParland remained undercover for two and a half years, finally taking the stand to testify. His evidence resulted in 59 guilty verdicts and the execution of 21 Mollies. His undercover work would follow him for the rest of his life, and not always in a good way. On one hand, he brought a group of very, very bloody men to justice, but on the other hand, he was shunned for turning on his own kind.

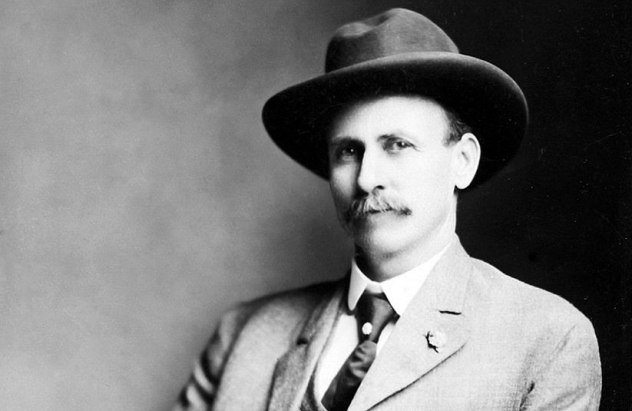

2 Charlie Siringo And The Bloody Coeur D’Alene Uprising

The Pinkerton Detective Agency is one of those organizations that manages to be just as hated in history as it is lauded, in large part because of their support of capitalist business owners and their opposition of labor unions. The writings of Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo provide a unique view into the mentality of Pinkerton detectives who fought unions.

Siringo was dispatched to a conflict between mine owners and labor unions in northern Idaho. Because of his support of the working man, he had originally declined the assignment and went off on another job instead. By the time he got back, there was still a need for the Pinkertons’ undercover work in Idaho. He went, with the stipulation that he didn’t have to do anything he didn’t agree with.

Siringo met with the mine owners who had called him in and eventually joined the labor unions. What he found was that the head of the union was, in his words, a “true blue anarchist” named George Pettibone. Once he saw what the labor unions were doing, not only did his sympathies change, but he stayed on.

While the popular opinion was that the labor unions represented the hard-working, downtrodden everyman who was being taken advantage of, Siringo reported some pretty horrific things. Those that broke the strike were dragged from their homes and shown the way out of the state (and encouraged to head that way by gunfire). It was clear that anyone who opposed the union was destined for the same sort of treatment. Those who joined the union swore to remain loyal to it or face death for their betrayal, and Sirigino, when he was finally recognized as a Pinkerton, found out that they weren’t kidding. He was sentenced to be burned at the stake but managed to escape union custody.

He fled, regrouping with the miner’s association, and was later appointed a United States deputy marshal and given the men he needed to put an end to the bloodshed in the name of fairness. They arrested around 300 union men, and the whole thing ended in 18 convictions.

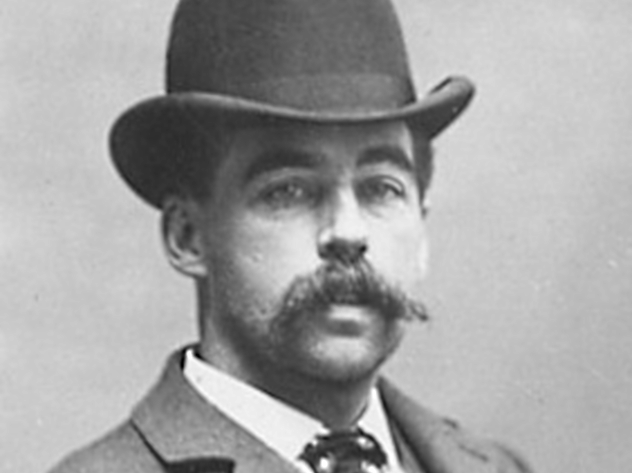

1 Frank Geyer And H.H. Holmes

Everyone knows the names of famous serial killers, but less familiar are the names of their victims. In 1895, Pinkerton detective Frank Geyer was in Toronto, looking for two young girls who had last been seen in the company of H.H. Holmes (pictured above). He was currently being held in Philadelphia, but the girls were still missing.

Holmes wasn’t just a murderer; he was also involved in insurance fraud. He hooked up with a man named Benjamin Pitezel, and they agreed to take out a $10,000 insurance policy on Pitezel, fake his death using the body of another person, collect the money, and get away. Pitezel’s family was in on the deal, but not the whole deal. Rather than switching out the bodies, Holmes cut out the pesky middle step and just killed Pitezel himself.

Pitezel’s wife, who knew about the scam, sent her 15-year-old daughter, Alice, from St. Louis to Philadelphia to identify the body. The ID was made, but Holmes then convinced Pitezel’s wife that her husband was traveling to keep the heat off. With a promise to take the children to see their father, Holmes kept Alice and was sent eight-year-old Howard and 11-year-old Nellie. After a few more moves, Holmes, the children, and his own wife, Georgiana, headed to Toronto.

Holmes received the payment, but he hadn’t paid off a former cellmate who’d been instrumental in setting the whole thing up. Authorities started to get suspicious, and the Pinkertons stepped in, arresting Holmes.

Geyer headed to Toronto, having determined that by the time Holmes had moved to Canada, the boy was no longer with them. Concentrating on finding the girls, he retraced Holmes’s movements in the city, finding that somehow, Holmes had managed to keep up a pretty impressive charade, traveling with both the Pitezels and his wife, without either party being aware of the others.

Coming to the conclusion that he had rented a house and killed the girls there, Geyer held a press conference and appealed for help in finding the missing Alice and Nellie. After a handful of dead ends and false leads, they tracked Holmes to a house on St. Vincent Street and spoke with a landlord who remembered the new tenant asking for a shovel—and permission to dig in the basement, presumably for a root cellar. Alice and Nellie were found; their remains were identified by their mother.

After the discovery, law enforcement began looking at Holmes for much, much more than just insurance fraud.