Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

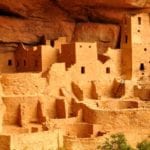

10 Anthropological Hoaxes And Fake Civilizations

Even if you know that places like Atlantis aren’t real and that there’s unlikely to be any lost civilizations still kicking around the world, it’s tough not to be captivated by the stories. The myths of not-yet-discovered societies and secrets of how we’ve developed as a species are easy to be drawn into. Sometimes, we believe fantastic and impossible stories simply because we want to.

10 ‘Tribal Rites Of The New Saturday Night’

On June 1, 1976, New York Magazine published a fascinating expose on a mysterious new subculture among the disco generation. Nik Cohn’s article was called “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” and he focused on new rites of passage, fashion, jargon, and rituals of the 16- to 20-year-old crowd. Gone were the days of the ’60s rocker; in came disco with its flowered shirts and overcoats. For those outside the scene, it was a strange, otherworldly culture.

The article focused on one small, close-knit group. Cohn’s “tribe” was led by Vincent, the best dancer in the area. Clubs paid him to frequent their establishments. When Vincent took to the dance floor, everyone else cleared a path. But that kind of fame didn’t come without a price.

The next year, Saturday Night Fever was released, all based on Cohn’s article. John Travolta gave a face to Cohn’s subject, and the movie became the embodiment of disco culture.

It wasn’t until 1994 that Cohn admitted that his entire article had been made up. There was no Vincent, and he certainly didn’t know anything about the disco scene he wrote about—he wasn’t even familiar with the part of New York City that it had been set in. He had only just moved to the city, didn’t know anything about it or its people, and based Vincent on a mod rocker he’d known in the ’60s.

Cohn not only helped to create disco as we know it based on a story he invented, but in 1983, he was indicted for his involvement in a drug trafficking ring that had brought about $4 million in Indian heroin into the country. Ever the convincing raconteur, he talked his way down to a $5,000 fine and probation in exchange for his testimony.

9 The Veleia Affair

In 2006, Spain was ecstatic. During an excavation of the ancient Roman city Iruna-Veleia, a team of archaeologists led by Eliseo Gil found artifacts that could have overhauled our understanding of the people who lived there. Pieces of pottery that were dated around the third century were etched with images from the crucifixion of Christ. Egyptian hieroglyphics were scratched into other objects. They even found messages written in the Basque language, which would have pushed back its development by about 700 years.

The implications were staggering, and these discoveries would have put the city—and the dig—right in the middle of the Roman Empire’s history. Dates were confirmed, scientific data was gathered, and experts were consulted. In the end, about 600 pieces of anachronistic pottery were unearthed. Once it was organized, it covered Roman and Egyptian history, early Christian history, Greek and Roman gods, and Egyptian royalty.

If it sounds too good to be true, it was.

Eliseo Gil was accused of destroying pieces of national heritage and fraud, but the story was more complicated than that. At the same time, skeptics were admitting that there were probably some authentic finds in the mix. Others claimed that there was way too much suspect evidence for any of it to be believed. Gil was ultimately removed as director of the dig site, and he, the artifacts, and the legitimacy of the entire dig were all called into question. Gil continues to proclaim his innocence and points to mistakes made by the Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain in identifying the artifacts.

Among the evidence were the letters “RIP” on a description of Christ’s crucifixion, which conflicted with the idea that he would be resurrected. At the time, that suggestion would have been nothing less than heresy. There were also names inscribed on the artifacts that weren’t in use until the 19th century and a reference to the works of Descartes. Perhaps the most damning of all was the discovery of modern glue used on some of the pieces.

8 Stotham, Massachusetts

The April 1920 issue of the White Pine Monograph Series (which is literally a publication about buildings constructed with white pine), featured buildings in a town called Stotham, Massachusetts. The issue featured a number of pictures of the town’s architecture, including its churches and mansions. There was a small town history that mentioned Zabdiel Podbury and Drusilla Ives leaving England and settling in New England. The feature also mentioned a local haunted house and other buildings that the townspeople went out of their way to preserve.

For decades, no one noticed that there was no such place as Stotham. It was only when the Library of Congress added the White Pine Monograph Series to their archives that they realized there was no other mention of the city or the people. They searched through historical records and through decades of maps, but there was no Stotham.

Finally, they asked an editor of the publication what was up.

Stotham had simply been invented as a way to use some of the drawer full of photos they had left over from previous editions. There were a lot of leftovers, and many of them were too good to go unused and unpublished. So they made up Stotham, its people, and its history to create their own charming New England town.

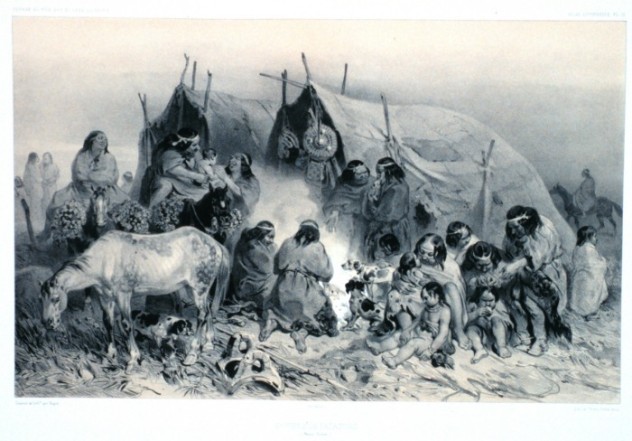

7 The Tasaday

In 1971, anthropologists claimed to have found an isolated civilization never before touched by modern society. They were living in a remote, wild area of the Philippines, and they hadn’t advanced technologically past the Stone Age. They were called the Tasaday people.

The Tasaday were living a life that was in tune with nature. In order to make sure they were allowed to stay that way, thousands of acres were set aside just for them.

Some anthropologists were suspicious, though, noting that the berries and tadpoles that the Tasaday supposedly lived off of would only account for a small portion of the nutrition human beings need to survive. After declaring they were going to investigate further, the anthropologists were banned from interacting with the tribe. Not long after, violence in the Philippines discouraged further investigation. For years, the Tasaday were left to their own devices.

In 1986, Manuel Elizalde, who had originally discovered the tribe, got word of new efforts to study the Tasaday. When claims were made that the Tasaday were clearly a hoax, he recruited the help of the president of the country. The Tasaday were declared legally authentic, but that didn’t exactly clear up any doubts.

A number of confusing claims and facts surrounded the tribe and fueled the controversy. Their language was markedly different from other local tribes, and the Tasaday later retracted some of their previous statements that they had been bribed to live the life of a Stone Age tribe. There were a lot of conflicting statements, and it’s generally accepted that while they were undoubtedly an isolated group, they weren’t the Stone Age people they pretended to be. The argument still hasn’t been settled, long after Elizalde took off with the money he’d raised to support the Tasaday—around $35 million—and a new harem.

6 Uluru’s Ancient City

World News Daily Report is a satirical website, and their disclaimer states that it would be a downright miracle if anything on the site were in any way close to the truth. In 2014, they ran an article about a team of archaeologists from the Australian National University who were excavating the area around Uluru, a massive sandstone rock formation also known as Ayers Rock, when they found the remains of an ancient city. They dated the city to around 1,500 years ago, and the sheer number of buildings—temples, palaces, reservoirs, and homes—seemed to indicate that it wasn’t just a city, but that it was possibly the capital city of a civilization that had been previously undiscovered. It was home to an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people, and it was obviously the center of a flourishing society that mined gold and traded their wares across the world.

And Australians got mad.

Commenters on the site were enraged that the article would distract from issues surrounding the aboriginal people of Australia. The story was shared again and again, and countless people went straight to the “source.” The archaeology department at the university was flooded with inquires about this new civilization. They took it all in stride, hoping that they might see a spike in enrollment numbers after the fictitious story broke, and also noting that the mysterious—and completely fake—city is much more exciting than their usual finds.

5 The Patagonian Giants

Without a doubt, Ferdinand Magellan saw some incredible things on his journeys across the world. But according to a book written by one of his expedition scholars called Magellan’s Voyage: A Narrative Account of the First Circumnavigation, those incredible sights included the of singing, dancing, naked Patagonian giants of South America.

According to the story, Magellan and his crew first saw a giant dancing on the shores. When they stopped, the giants offered them food and drink as a token of friendship. The explorers were accepted into the tribe, presenting their new friends with all sorts of European trinkets. The gifts included a mirror, and the giants were at first horrified by their massive, monstrous appearance. According to the report, the Europeans were only about waist-high to the giants.

Magellan’s plan was to use their obsession with shiny things to distract them long enough to chain them and put them on the ship to bring back to Europe. While this sounds almost farcical, it was absolutely in line with the usual reaction of European explorers who stumbled across native people. Unfortunately, the giants were said to have died on the ship.

About a century later, Sir Francis Drake returned to the area and made contact with the locals. He proceeded to call Magellan out on his lie, stating that while they were a bit bigger and a bit stronger than Europeans, the rest of the claims were bunk—especially claims that the average Patagonian was about 3 meters tall (10 ft). We can’t be sure whether Magellan simply exaggerated when he met his Patagonian giants or if he actually did meet someone who was abnormally tall, but we do know that the race never existed as he reported.

4 The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

The myth that there are some ancient civilizations lost beneath North America is a pretty popular one among historians and anthropologists on the fringes of mainstream academia. In 1909, the Arizona Gazette ran a story that seemed to confirm all their wildest dreams. Better yet, the news came with two reputable researchers from the Smithsonian.

Supposedly, the Smithsonian archaeologists had found a city in a series of caverns sitting in a remote, largely unexplored section of the Grand Canyon. The city was filled with relics that clearly linked their founders to ancient Egypt. The civilization that inhabited this city must have been the oldest in the United States. The article went on to detail a shrine that contained the statue of a cross-legged figure holding a lotus flower, a crypt that contained mummified remains and urns, and walls that were decorated with hieroglyphics.

The article also specified how it had gone for so long without being discovered. The entrance was on a sheer cliff face in the middle of nowhere.

The Smithsonian has denied there was ever any such place or any such artifacts found in the United States. The lack of a paper trail of any sort or record of the archaeologists named in the article seems to support their dismissal. But the story hasn’t gone away—quite the opposite. It’s become a legend among pseudohistorians and conspiracy theorists who are convinced that the Smithsonian is staging a cover-up. Conspiracy guru John Rhodes claims that he knows where the caves are and that they’re under constant guard. David Hatcher Childress also claims that the discovery is absolutely real and that someone clearly doesn’t want the rest of us to know the truth.

3 Vilcabamba

Vilcabamba is a real place, and it’s beautiful. Sitting high in the Ecuadorian Andes, the village was the subject of a 1970 study that investigated the connection between heart disease and different diets. The scientists reportedly found much more than the connection when they discovered that the villagers not only had low cholesterol and few instances of heart disease, but that out of the 819 people who lived there, nine of them were over 100 years old. At the time, the entire United States only had about three centenarians per 100,000 people. Some claimed ages of 140 and upward, and they seemed to have the birth certificates and records to back up these claims.

Not surprisingly, once word of the longevity of residents got out, the little village gained a reputation as a paradise on Earth. There were several books written about the town, all praising the villagers’ one-with-nature lifestyle. They worked the land, hiked, composed poetry, and always stayed active.

Also not surprisingly, other people started to get suspicious. When Harvard Medical School visited, they recorded one villager who claimed to be 122 years old. When they went back three years later, he said that he was 134. Further investigation uncovered a very different truth—that there were actually no people over the age of 100 in the village at all. It was all a cultural misunderstanding. For generations, elders had been venerated above all others , so in order to raise their status within the community, they exaggerated their ages. When they did the same thing with the original outside researchers, they took them at their word. And the birth records? There’s a widespread practice of using the same names over and over.

The idea that there’s a magical quality about Vilcabamba hasn’t gone away, though. Today, people still head to the little village hoping to attain magical longevity, but they never find it.

2 Fawcett’s Brazilian Idol

We’ve talked about Colonel Percy Fawcett and his search for the lost city of Z before. He certainly didn’t come up with the idea of a lost city in the wilderness of South America on his own, and how the story was built is as fascinating as his failed journey to find it.

Fawcett became convinced of the reality of the lost city because of a 25-centimeter-tall (10 in) basalt figurine that was given to him by the writer H. Rider Haggard. Haggard, who wrote mostly about things that put him in the field with ancient astronaut theorists, had supposedly gotten the mysterious figure from Brazil and was unable to figure out what it really was. He said that he believed it was authentic and ancient.

Once Fawcett got it, he took it to a number of experts (including those at the British Museum) for their opinions. When he was unsatisfied with their analyses, he tried some psychic mediums instead. According to one, the idol was connected to an advanced civilization that had inhabited a continent between South America and Africa, long before the ancient Egyptians came to power. The civilization had been destroyed by a volcano. A psychic also claimed that the idol had once belonged to a high priest, who had handed it to his successor with instructions that it should only pass into the hands of those who are appointed to the priesthood.

The idol itself depicted a bearded man holding a tablet, and the engravings on the tablet match absolutely nothing else we’ve ever seen and no language known to man. Unlikely as it might have been, the idol and the air of mystery surrounding it convinced the explorer that his civilization was out there, and all he had to do was go find it.

1 The Lost City Under Moberly, Missouri

If there are really any lost cities out there, we’re pretty sure they’re going to be found someplace remote and uncharted. Nowhere in Missouri fits that description, but the town of Moberly claimed it had found an incredible lost city in 1884 when workers were digging a new coal mine.

According to the story, Tim Collins was leading a mining operation that was originally looking for coal (and later for black diamonds). He kept digging deeper and deeper without finding anything worth the time or effort, but Collins persevered. Finally, they broke into a giant underground chamber, colorfully described as a “vast cavern of indescribable and awe-inspiring wonders.” There were chambers of obvious human construction with stone benches, tools, and idols. As they continued to explore, they stumbled across a massive human skeleton. The chamber had opened into what looked like a wide street. The skeleton was beside a stone fountain. The femur alone was 1.4 meters (4.5 ft) long. In total, it was about three times the size of a normal human, too big to remove from the chamber.

The story went 19th-century viral, picked up by newspapers across the country. Even though it obviously wasn’t true, there were enough true details—like the existence of Tim Collins and his coal mine—to help the story along a little bit. In 1905, the same paper ran a retraction saying that it had all been a joke. For most people in the town, it was a lucrative legend that brought in sightseers and tourists who otherwise never would have stopped by Moberly, Missouri.

The only person who was really fed up with the whole thing was the erstwhile Tim Collins. He became so sick of people visiting him in an attempt to catch a glimpse of the ancient city and all its treasures that a sign finally showed up on his property: “No burryied sity lunaticks aloud on these premises.”