Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Bizarre Funeral Customs From Around The World

Death can be a very personal and upsetting thing, but it can also be a very spiritual and communal occasion. It’s something that has affected us since before we were even human, and it makes up 50 percent of life’s certainties (for the time being, anyway). How societies treat their dead is one of the most insightful ways to learn about their customs, religion, social life, hierarchies, art, technology, and pretty much everything else you can think of. But there are a lot of people in the world, and we’ve been around for a long time, so it was inevitable that we’d come up with a few strange reactions to death.

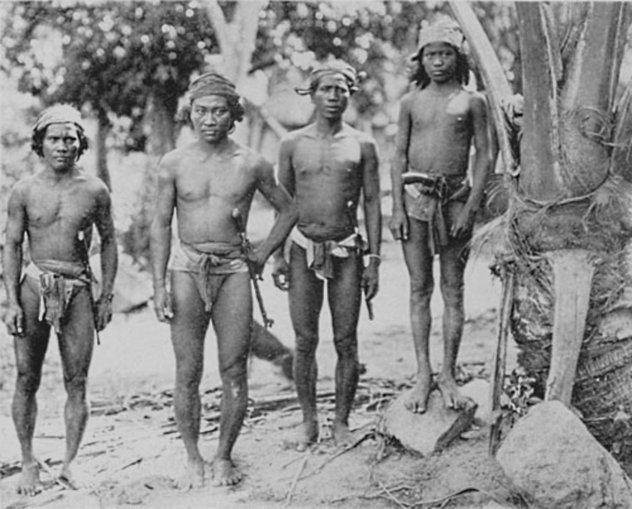

10 Ifugao Funerals

The native tribes of the Ifugao province in the Philippines go by many names, so we’ll just stick with “Ifugao” to keep things simple. When a member of an Ifugao tribe dies, those close to the deceased will set to work at preparing for the mourning process, although the spouse is expressly forbidden from having anything to do with this process. Male relatives will build a chair, which will be used to prop the dead body up for the mourning period (up to eight days).

The body is washed, blindfolded, and set up near the front door of the house, with a fire burning nearby the entire time. This serves to keep away insects and to dry the corpse out. The spouse is forbidden to see the body once people have started to bring offerings, which they are also forbidden to indulge in. This means that spouses usually spend the mourning period in other rooms of the house or in another house entirely. If they have only one room, they may share it with the corpse, provided they don’t look at it.

On the fourth day of the mourning period, the body is taken out of the chair, and its skin is peeled off. This is one of the most popular parts of the funeral, as the tribesmen believe it helps with fertility. The skin is then buried underneath the house of the deceased. The body may also be buried on the fourth day or kept out for another four. Whenever it is ultimately buried, it is also placed under the house of the deceased.

Sometimes, several years after the funeral, someone close to the deceased may experience symptoms that are said to be caused by the soul of their late friend or family member. This requires the bones to be exhumed so that the spirit can join them in a feast. The bones are then given a second funeral.

9 Itneg Funerals

The Itneg people, commonly referred to as the Tinguian by outsiders, are another tribe not far from the Ifugao tribes in the Philippines. Because of their close proximity, their funeral customs share some similarities but are still quite distinctive.

Like the Ifugao, the Itneg bathe the body of the deceased, dress it to the nines, and prop it up in a specially made chair. That’s pretty standard stuff so far, but the Itneg have a lot of evil spirits that need to be warded off, so there are several steps that must be taken to remain safe. For example, there is a spirit named Kadongayan, who likes to show up and cut the mouth of the deceased from ear to ear, Joker style. To prevent this, pig intestines are hung outside the door for the duration of the corpse’s display. On top of that, a live chicken has its beak broken and is hanged by the door near the corpse as a sort of message to Kadongayan, who thinks that the same will be done to him.

Dishes are placed below the body to collect any fluids that run out. They will be placed in the grave along with the body. Ibwa is the name of a spirit who used to amicably drop by funerals until he was accidentally handed one of these dishes. Now, he has a taste for human flesh and fluids, so he comes along with his friend, Selday, to feast on the dead.

Akop is a spirit who tries to bring death to the husband or wife of the dead person. He has no body and is just a head accompanied by some slimy limbs. The spouse must hide behind pillows to escape him and sleep in a fishing net for three days. On the third day, the village warriors must go headhunting, usually in a neighboring tribe’s territory.

The body is buried under the house, as this is the best way to keep the deceased safe from the spirits. Mourners are whipped and painted with a little bit of pig blood and oil, and then they are free to resume life as usual. Once this is all done, the mourning period ends for everyone except the spouse, who must mourn for another three months.

8 Aseki Corpses

The Anga people are an extremely isolated mountain tribe in the Aseki district of Papua New Guinea. Although the tribe has been studied for over a century, their isolation has led to a number of conflicting reports as to the origins of the mummies dotted around the area. In addition to reports that the tribe practiced cannibalism, which some locals say was practiced on the island but not with them, there are also claims that they drained body fat from the dead and used it to cook.

What is indisputable is the fact that there are a number of mummies in the region that are curled up in baskets or propped up with bamboo. Some say that these mummies were embalmed using salt during World War II. The more popular theory is that the mummies were created as part of a centuries-old ritual that involved smoking corpses for months on end before covering them in red clay. Christian missionaries brought the practice to an end in 1949, although the locals continue to maintain the mummies, which can be found in a number of areas in the region to this day.

7 Tongan Kings’ Funerals

Tonga is a small nation spread across roughly 170 islands in Polynesia and is the last remaining kingdom in the South Pacific. Their monarchy stretches back over 1,000 years, and although the last king, Tupou V, enacted a number of changes to make the country more democratic, they still treat their royal families with extreme reverence. The rules surrounding the burial of their kings are the most telling example of this reverence.

Tongan kings are considered to be so important that nobody is allowed to touch them during their life, and only a select few may touch them after their death. These people are known as nima tapu, which translates to “sacred hands.” Once these people have prepared the king’s body, they must spend the rest of the mourning period locked away from the public. During this time, they are forbidden to use their hands at all. The mourning period lasts for 100 days.

Since that is a very impractical rule, the nima tapu have servants to shower them with their every desire while they await the end of the mourning period. It’s not a bad deal, considering that the old method of dealing with the issue of people touching the king’s body was to either kill them or chop off their hands.

6 Ngaben

Ngaben is an elaborate ritual performed in Bali to cleanse the spirit of a deceased person and help guide them to the afterlife. Similar to many cultures, Ngaben is a celebration of life rather than a mourning of death, as death is viewed as the time when a person is able to move to the afterlife before being reincarnated.

Before Ngaben starts, the body is laid in a bale delod, a small bedroom, while the family goes about life as normal, acting as though the person is simply sleeping. The body is then buried in a temporary location, a small temple called a pura dalem, until the family can save enough money for the ceremony. When that time comes, the coffin is placed in a beautifully colored and detailed tower that can be as high as 9 meters (30 ft).

A procession is held, and the tower is brought to the place of cremation, carried by young men who spin and walk in an erratic manner so the soul cannot find its way back. The body is placed in a bull-shaped sarcophagus, which is then set alight. The ashes are collected and scattered into the sea to cleanse the soul.

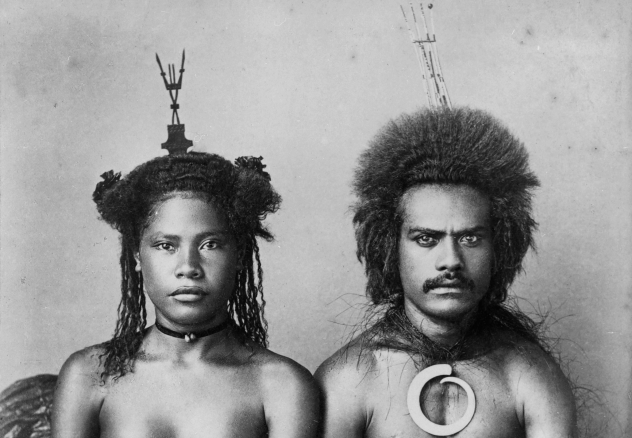

5 Fijian Funerals

Fiji is a pretty small country, so it’s not surprising that some of their more unusual traditions were practiced by a number of different tribes across the islands. One death tradition was the killing of healthy family members, which could happen in one of two ways. The first is that a person would approach their parents (or vice versa) and let them know that enough is enough. They’ve become too much of a burden, and it’s time to call it quits. The family would then discuss whether the parents would like to be strangled by their own children or buried alive, but the actual dying part was non-negotiable.

If it was a tribal chief who died, there was a nine-day period where women lashed men with shell-lined whips, while the men used bamboo to fire hard clay at the women. Self-inflicted wounds were also a common way to mourn. This would include people cutting off their own pinky fingers or toes, while women would also burn themselves.

The final and most famous practice was to strangle people the deceased was close to during life. This usually included, but was not limited to, wives of deceased men. The belief behind this was that they could accompany the dead to the afterlife. A major influence on this culture of voluntary death was also the fact that many Fijians believed that you enter the afterlife in the same state as you left life, which means any disabilities or disfigurements would be with you forever. Therefore, many believed it was better to make the move when they were healthy, rather than risk being maimed for all eternity. Unsurprisingly, the popularity of this tradition dwindled in the 20th century.

4 Caviteno Tree Burials

The Caviteno are a Spanish-Filipino ethnic group from the Cavite region of the island of Luzon. Although they are on the same island as the Ifugao and the Itneg, they are quite far away from those groups, so their funeral customs are quite different.

Relative to the wide range of funeral customs practiced around the world, Caviteno burials are quite tame and natural. Rather than mummification, cremation, or even a straight-up burial, the Caviteno inter their dead inside trees. Bodies are placed vertically in hollow tree trunks, as the Caviteno believe that since trees give us life, we should return the favor and help give them life by giving up our bodies to them when we die.

The specific tree to be used is usually selected by the deceased themselves before they die, either when they are getting old or are close to death for some other reason. The whole concept is not dissimilar to the use of tree pods, which have become a popular alternative to coffins in recent years.

3 South Korean Cremation

With an area of about 100,000 square kilometers (39,000 mi2) (roughly the size of Kentucky or half the size of Britain), South Korea isn’t exactly a huge country. Add in the facts that there are about 50 million people living there and that it is a very mountainous region, and you’re left with a big problem—burial space.

To address this issue, the South Korean government passed a law in 2000 that required families to remove their loved ones from their graves after 60 years. This grim law caused the number of burials to halve over the next decade, to the point where 70 percent of people opted for cremation. But since South Korean culture calls for a high level of respect for one’s ancestors, a number of people are unhappy with simply turning their relatives to ash. This has led to the foundation of Bonhyang, a company that will take those ashes and turn them into beads using heat.

The beads come in a variety of colors, and the number of beads produced depends not only on the size of the individual, but also on their age, as younger people have a higher bone density and produce more ash. As many as eight cups of beads can be produced, but they are not worn as jewelry. Rather, they are placed in clear jars and displayed at home, giving people a beautiful way to remember their late relatives.

The idea was brought over to the United States but never gained popularity and is now mostly confined to South Korea. If beads aren’t your thing, it’s also possible to have cremated remains turned into a diamond.

2 El Muerto Parao

El muerto parao, or “dead man standing,” is a new trend of alternative wakes in Puerto Rico. Instead of the traditional open casket, the Marin Funeral Home will create a diorama representing the deceased person’s life, with the centerpiece being their own propped-up corpse.

Damaris Marin, the director of the Marin Funeral Home, says that she has developed a secret method of embalming that allows her to create these elaborate scenes. For a while, there was some question as to whether the whole process was legal, but it was ultimately decided that no laws were being broken by displaying the bodies this way.

One example has a propped-up Christopher Rivera, a boxer who was shot dead at age 23, in the corner of a ring. Family and friends were able to pose for one last photo with his body. Other examples include David Colon posed as though he were riding his motorbike, Edgardo Velazquez displayed in his ambulance, and Fernando de Jesus Diaz Beato displayed with his eyes open in March 2016. He was the first to be shown in this manner, and it was supposed to be a nice surprise for the family.

1 Ma’nene

While many cultures have bizarre ways to bury or cremate their dead, one group likes to get them back up again. The Torajans are indigenous Indonesians who like to take out the corpses of their dead family members every three years and parade them around town.

Seen as a way to honor the memory of the dead, the Ma’nene ritual is a time to exhume the bodies of loved ones, change their clothes, clean them up, and spend a little quality time with them again. In addition to the new clothes, family members will tend to the bodies by mummifying them to ensure that they stick around as long as possible. One man, Piter Sampe Sambara, has been dead for over 80 years, which means that his body has undergone this ritual over 25 times. Although he doesn’t look particularly appealing, he doesn’t look that bad considering that he died in 1932.

Simon Griffin likes to adhere to Irish stereotypes, such as drinking, loving the potato, and burying people without putting their corpse on display. You can follow him on Twitter here.