Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Ancient Prosthetics

Prosthetics are not a modern invention. For millennia, physicians and craftsmen have built replacements for body parts that people have lost through injury, amputation, or disease.

Today, few ancient examples survive because their construction of wood and organic material decayed quickly. Of those that remain, many are elegantly engineered machines, resembling cybernetics more than peg legs. Other ancient prostheses are shrouded in mystery, and our knowledge of them has only come through legend.

10 Cairo Toe

Dated between 950 and 710 BC, the “Cairo toe” is the oldest prosthesis in the world. Archaeologists discovered this artificial big toe on a female mummy near Luxor.

The Cairo toe is composed of leather, molded and stained wood, and thread. Ancient Egyptians frequently created false body parts for burials. However, tests on toeless volunteers revealed that this ancient prosthesis was functional as well. It made walking in Egyptian-style sandals significantly easier, and the lack of pressure points made it comfortable for extended use.

Archaeologists have discovered other ancient prosthetic toes in Egyptian graves. One dated to 600 BC is composed of a paper-mache mixture known as cartonnage. Experiments revealed that this style of prosthesis was uncomfortable and could not bend. However, they made excellent cosmetic replacements for missing digits.

9 Golden Eye

In 1998, archaeologists unearthed the oldest artificial eye in the world. Dated to 5,000 years ago, the prosthesis was discovered at the necropolis of Shahr-i-Sokhta in the Sistan desert on the Iran-Afghan border.

A half-sphere with a diameter of just over 2.5 centimeters (1 in), the lightweight eye was made from bitumen paste. Intricate engravings create a central iris bursting with rays of golden light. Traces of gold are still present, suggesting that the eye was once cloaked in the material.

Between 25 and 30 years old, the woman who wore the eye was nearly 183 centimeters (6′) tall, making her a giant in 2900 BC. She was also buried with an ornate bronze hand mirror.

Initially, the research team thought that the artificial eye had been placed in the grave after her death. However, a microscopic investigation revealed an imprint on her left eye socket from extended contact with the prosthesis.

8 Gotz Of The Iron Hand

Gottfried “Gotz” von Berlichingen was an infamous German mercenary with a prosthetic arm that matched his fearsome reputation. During the 1504 siege of Landshut, Gotz lost his right arm to a cannon blast. He survived and commissioned armor with an artificial iron limb.

Internal gears controlled the articulated fingers of the iron prosthesis. The new limb was strong enough to handle a sword and delicate enough to clutch a quill. For 40 years, “Gotz of the Iron Hand” continued to terrorize the German countryside.

Born nearly 500 years ago in Wurttemberg, Gotz was a knight of the Holy Roman Emperor but spent much of his time robbing merchants and noblemen. He is now remembered as a Robin Hood–like figure. Gotz’s groundbreaking prosthesis is celebrated by Germans as a symbol of their national ingenuity.

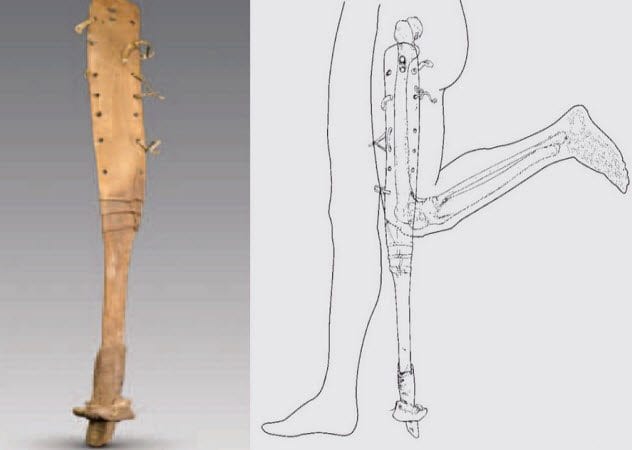

7 Hoofed Prosthetic Leg

In 2007, archaeologists unearthed a 2,200-year-old hoofed artificial leg in Turpan, China. The prosthesis was attached to a man between 50 and 65 years old.

His patella, femur, and tibia were fused together at an 80-degree angle, making it impossible to walk normally. The prosthetic leg contained a horse foot at the bottom. Wear at the top of the prosthesis revealed that it had been used for years.

Some speculate his knee condition was the result of inflammation. The man once suffered from tuberculosis, which may have resulted in bony growth with the potential to fuse the knee together.

The bone’s smooth surface suggests that the inflammation stopped years before his death. Modest grave goods indicate that the man was of modest means. Based on radiocarbon dating, experts believe he belonged to the ancient Gushi people, who were conquered by the Han dynasty in the first century BC.

6 Tycho Brahe’s ‘Silver’ Nose

Born in 1546, Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe made the most accurate measurements of planetary bodies without a telescope and discovered that comets were beyond our atmosphere. In 1566, Brahe lost his nose in a duel with Manderup Parsberg. They had fought over a math formula. For the remainder of his life, Brahe wore a prosthetic nose that historians believed to be made of silver.

When Brahe was exhumed in 2010, researchers discovered that his famous “silver” nose was not really silver. Although they were not able to locate the actual prosthesis, traces of zinc and copper were found in greenish colorations around the nasal cavity.

Researchers concluded that his prosthetic nose must have been made of bronze. Brahe had inherited a vast sum of money from his foster father, Jorgen. With one percent of Denmark’s wealth after his inheritance, Brahe may have had a gold nose for special occasions.

5 Anglesey Leg

Sir Henry Paget, Lord of Uxbridge, lost his leg to a cannon blast while commanding the British cavalry at the Battle of Waterloo. Uxbridge was carried from the field and survived an above-knee amputation.

During the procedure, which was performed without antiseptics or anesthesia, the stoic nobleman noted simply that “the knives appear somewhat blunt.” Stored at Waterloo, his severed leg was a popular tourist attraction for decades.

James Potts designed the patented “Anglesey Leg” to replace Uxbridge’s missing limb. Most prostheses of the time were peg legs. However, the Anglesey Leg was a work of art.

Constructed of carved fruitwood, the articulated leg was controlled by a delicate system of kangaroo tendon strips, allowing flexibility of the knee, ankle, and toes. Less limber prosthetics frequently got tripped up on cobblestones.

4 Recycled Teeth

While investigating Tuscany’s San Francesco monastery, archaeologists discovered the earliest known dental prosthesis in the world. The 400-year-old dentures were made of real human teeth—three central incisors and two lateral canines—bound together with a golden band.

The roots of the teeth were partially removed before incisions were made along their base. The teeth were then aligned and secured into place with a gold lamina. A CT scan revealed minute gold pins fixing the teeth to the internal gold band.

Archaeologists have long known about ancient dentures through written accounts. However, this is the first tangible discovery. The teeth were found in a noble family’s tomb containing 100 corpses.

Researchers have been unable to match the dentures to any of the mandibles. The owner remains a mystery. The buildup of plaque and calcium on the dentures suggests that they were worn for an extended period of time, perhaps years.

3 Ancient Austrian Peg Leg

In an ancient Austrian cemetery, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a sixth-century warrior who had a prosthetic leg. Experts believe the limb was amputated in battle. The evidence of the ancient prosthesis came from an iron ring above where the foot should have been attached.

Detecting osteoarthritis, experts believe the man once used a crutch. Experts speculate that the prosthesis was a wooden peg leg reinforced with an iron band at the bottom. Stains on the leg bones suggest that leather was used to secure the prosthesis.

Researchers believe the knight was between 35 and 50 years old. He was buried with an ornate brooch and a short sword. A CT scan revealed that he had a healed broken nose, multiple cavities, and arthritis in his hip, shoulder, spine, and left knee. Two lower leg bones contained cavities, suggesting an infection.

Although amputations predate the sixth century, the knight’s mid-bone severing remains unique.

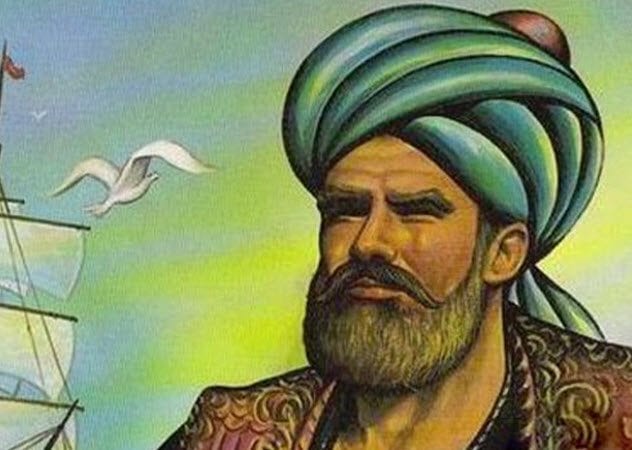

2 Barbarossa’s Silver Arm

In the 16th century, the infamous Barbary Coast pirate Aruj Barbarossa was known as “Silver Arm” for his glimmering prosthetic limb. During a battle with the Spanish in Algeria in 1512, he sustained a cannon shot that blew away his left arm above the elbow.

His men carried their unconscious commander to Tunis, where highly skilled Arab surgeons amputated the shattered limb. Then Barbarossa was outfitted with a special prosthesis made of shimmering metal.

Barbarossa eventually became sultan of Algiers. To protect his possession, he allied with the Ottomans, becoming a governor of their new province.

1 Capua Leg

In 1910, archaeologists unearthed a prosthetic leg in an ancient Roman tomb in Capua, Italy. At the time of its discovery, the Capua leg was the oldest artificial limb in the world.

Dated to 300 BC, the Roman prosthesis was constructed of bronze. Its function was to replace the lower portion of the leg below the knee. Researchers believe that a sheet metal waistband secured the leg in place.

The Capua leg was housed in London at the Royal College of Surgeons until it was destroyed in an air raid during World War II. A copy exists at the Science Museum, London.

Artificial limbs were not commonplace in ancient Rome. However, there were a few famous examples. General Marcus Sergius lost his arm during the Second Punic War. He commissioned an iron replacement. The new limb allowed him to hold a shield and continue engaging in combat.

Abraham Rinquist is the executive director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.