Animals

Animals  Animals

Animals  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

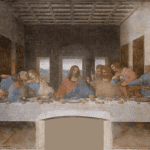

10 Outrageous Acts Committed by Renaissance Popes

The Renaissance was a vibrant period in history, taking place between the 14th and 17th centuries. The modern world emerged from the Middle Ages with the rediscovery of classical learning, art, and humanism. There was marked improvement in the human condition: intellectually, economically, and socially. But spiritually? The Universal Church that was supposed to guide souls has had a long history of venality and corruption, but the increasing secularism of the age seemed to have aggravated the symptoms. The Renaissance Popes behaved no differently from the power-hungry princes of the time, provoking the Protestant secession and the rending of Christendom.

Related: 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

10 The Slave Trade

With the Renaissance came the age of exploration and discovery, which opened hitherto unknown lands and peoples to European colonization and exploitation. The Portuguese exploring West Africa were the first to recognize the economic profits of a large-scale slave trading enterprise. In 1441, a Portuguese ship captain named Antam Goncalves made the first raid for the express purpose of kidnapping slaves, capturing less than a dozen, a small beginning for what would become a massive trans-Atlantic traffic in human beings.

Fifteenth-century jurisprudence regulated the treatment of captive Jews, Muslims, and Christians, delineating who was enslaveable and who was not. But the status of these “black Gentiles” was not so clear. In 1453, Pope Nicholas V (1397–1455) issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, giving King Alfonso V of Portugal the authority to reduce and enslave “Saracens (Muslims) and pagans and any other unbelievers,” effectively giving his sanction to the West African slave trade. On January 8, 1455, he followed it up with the bull Romanus Pontifex, granting Portugal the exclusive right to conquer and enslave the inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa.

It was Nicholas who gave religious justification for the detestable practice, suggesting that the conversion of the slaves to the True Faith was actually an act of piety and charity.

The Romanus Pontifex was a fateful and far-reaching document that is responsible for all the abuses, oppression, and horrors endured by Blacks down through the centuries, especially in the New World. It reverberated even long after the abolition of the slave trade in the Jim Crow South of post-Civil War United States.[1]

9 All in the Family

Nepotism, the bestowal of offices and favors upon a Pope’s relatives, had bedeviled the Church before. However, Pope Sixtus IV (1414–1484) raised it to new heights. He created a grand total of 34 new cardinals out of his nephews, friends, and allies, none of whom were qualified for the job. One nephew, Girolamo Riario, became the Captain-General of the Church, a powerful post with control over the papal military. Sixtus housed his sisters in Rome’s most luxurious homes, with everything they desired within reach. (Link 4)

A contemporary critic, Stefano Infessura, dismayed by the deluge of worthless appointees, speculated that Sixtus was a closet homosexual and that he distributed offices to his illicit lovers. He characterized Sixtus, who embroiled himself more in political feuds than shepherding the Church, as “an impious and unjust king, who had no fear of God, no love of governing the Christian people, with no affection for charity or love, only caring for dishonest pleasure, greed, and vanity.”

The Holy Father was not averse to waging war to promote family interests. To obtain the duchy of Ferrara for Girolamo, Sixtus encouraged Venice to attack it, but almost every Italian state rallied to its defense, thwarting the Pope, who was forced to sue for peace. The defeat was said to have hastened Sixtus’ death.[2]

8 Assassination in a Cathedral

Girolamo Riario, Sixtus’s nephew, resented the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de Medici, because he was standing in the way of the Captain-General’s efforts to consolidate papal territories in the region. He allied himself with the Medici’s political rivals, the Pazzi family, who plotted to eliminate Lorenzo. Using his family connection, Girolamo got his uncle, the pope, to back up the plan.

On Easter Sunday, April 26, 1478, the Pazzi assassins attacked Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano while they attended Mass at the Duomo Cathedral. Giuliano was killed, but Lorenzo, though wounded, managed to escape. That the attack took place on a solemn holy day in a sacred space shocked many. That the pope was an instigator of the crime would shock even more. Lorenzo’s allies took brutal, murderous revenge on the Pazzis, who were thrown out the windows of the Palazzo Vecchio, their corpses strung up and left to rot in the sun. The enmity between Lorenzo and Sixtus led to the pope placing the city under interdict, forbidding Masses and sacraments from being given.

Sixtus encouraged his ally King Ferdinand I of Naples to attack Florence, starting a war that dragged on fruitlessly for two years, throwing Italy into confusion and disorder. In 1480, Lorenzo and Ferdinand made peace, and Sixtus had to lift his interdict.[3]

7 Extermination of Witches

Giovanni Battista Cibo (1432–1492), father of two illegitimate children, was elevated to the Chair of Peter as Pope Innocent VIII in 1484 in a conclave marred by politics, factionalism, bribery, and riotings. His reign would be as corrupt and tumultuous as a result of his involvement in secular Italian politics and his struggle against the Ottoman Turks. In an unprecedented move, Innocent had the Sultan’s brother and rival come to live with him in the Vatican, hoping to use him as a bargaining chip to keep the Sultan at bay. A Muslim prince living in luxury at the very heart of Christendom disturbed many.

At least Innocent did not forget his spiritual duties. He battled the Waldensian and Hussite heretics and appointed the sadistic Tomas de Torquemada as Inquisitor in Spain. Torquemada’s name would become virtually synonymous with Inquisitorial terror and brutality. When Dominican friar Heinrich Kramer requested authority to hunt witches in Germany, Innocent responded with the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus of 1484, giving Kramer the go-ahead.

Together with another Dominican, Johann Sprenger, Kramer wrote what may be the most diabolical book next to the Mein Kampf. The Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) was the primer for witch-hunters, detailing the nature and depravity of witchcraft, how to detect witches, and how to prosecute them. Before this, it was held that witches were powerless against God, and they received relatively light punishment. Now, the Malleus lumped witches together with heretics, deserving of being hunted down and killed. Torture was recommended to ferret out the guilty.

Some theologians condemned Kramer’s book as unethical and illegal, but it had already stoked people’s fears and was considered an authoritative source on Satanism. The systematic extermination of witches had begun, and Malleus Maleficarum, with Innocent’s bull on the preface, guided the witch-hunters on their grisly task in the following deadly centuries.[4]

6 The Pope’s Mistress

Some popes had taken mistresses before, and loose morals were no scandal in Renaissance society. But the relationship between Alexander VI (1431–1503), the former Rodrigo Borgia, and Giulia Farnese, probably the most beautiful woman of the time, raised many eyebrows: Giulia was forty years younger than her lover. People mockingly called her the “bride of Christ.”

Giulia’s relationship with then Cardinal Borgia began when she was just 14 when she married Orsino Orsini. When he became Pope, Alexander moved her to Rome with him, leaving Orsini behind. Giulia’s family approved of the arrangement, knowing that their interests would benefit. They were not disappointed. Alexander lavished rich gifts upon Giulia and elevated her brother Alessandro to the cardinalship (he would later become Pope Paul III). Orsino was mollified by the bestowal of a lucrative career. The Farnese family rose to prominence.

When Giulia returned to her hometown to visit a dying brother and Orsino, her long absence from Rome drove Alexander to suspicion and jealousy. Accusing them of ingratitude, he threatened the Farnese and Orsini with excommunication and confiscation of property unless Giulia returned to him immediately. On the way back, Giulia was waylaid and kidnapped by French troops, and a ransom of 3,000 ducats was demanded from Alexander for her release. The money was surrendered without hesitation by the pope, who would have gladly paid 50,000 ducats to redeem his lover, according to the ambassador of Ferrara, as she was “everything to him—a heart and soul.”

For unknown reasons, Alexander and Giulia ended their affair in 1500, three years before the pope’s death. At age 30, Giulia was finally free and was married again, remaining with her husband for eight years until his death and spending the last two years of her life in Rome.[5]

5 The Banquet of Chestnuts

On the eve of Halloween, October 30, 1501, a banquet was held at the Papal Palace in the Vatican that would be remembered in history as a debauched orgy only the perverted Borgias would dare hold. The most detailed account of this event came from the master of ceremonies, Johann Burchard, a known hater of the Borgias, so historians are wary of slander and exaggeration. Yet his account of courtesans (a polite term for prostitutes) attending the festivities finds corroboration from another witness, who wrote that the ladies greeted guests with “a most shocking sight.” What he meant is left to the imagination. Or we can let Burchard supply the details.

Throughout the evening, the courtesans allowed their clothing to fall off little by little until they were completely naked. Clergymen then scattered chestnuts on the floor, initiating a game where the women crawled to pick them up with their mouths. Then the prelates joined in, doing the act with utter abandon, and prizes were offered to the one who could perform with the most women. All the while, the pope, his daughter Lucrezia, and his son Cardinal Cesare Borgia looked on with amusement.

Truth, half-truth, or slander, Burchard’s record illustrates how low the Papacy had descended during the Renaissance that people had no trouble believing it.[6]

4 The Warrior Pope

You know something is definitely wrong when the Vicar of the Prince of Peace personally leads an army wearing battle armor under the papal robes. But that was exactly how Julius II (1443–1513), who chose his name in honor of Julius Caesar and nicknamed the Warrior Pope, appeared in his numerous wars to restore the power of the Papal States. He conquered Perugia and Bologna in 1508 and joined the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai. After defeating Venice and recovering papal territory, Julius turned his attention to driving the French out of Italy.

Julius appointed Cardinal Matthaus Schinner, his field commander, who, like Julius, led the troops personally, wearing his red hat and robes and saying he wanted to bathe in French blood. More serious churchmen begged Julius to cease leading the army, which damaged the reputation of his holy office. The French ridiculed Julius, saying he was nothing more than a monk dancing in spurs.

In all these, people were left wondering how incessant warfare squared with the Pope’s mandate to care for Christ’s flock. The historian Francesco Guicciardini laments over those who “judge that it is the office of the Popes to bring empire to the Apostolic seat by arms and by the shedding of Christian blood, more than to trouble themselves by setting an example of holy life and correcting the decay of morals, for the salvation of those souls for whose sake they boast that Christ has set them as his Vicars on earth.”

Julius eventually succeeded in his political aims and was hailed as a liberator. But the price—a Church sinking deeper into disrepute—was to prove too high.[7]

3 Execution of Cardinal Petrucci

Giovanni de Medici (1475–1521) was just 38 when he was elected Pope Leo X in 1513, one of the youngest pontiffs in history. “God gave us the Papacy—let us enjoy it,” he was reported to have said. Enjoy it he did, and Leo’s reign was one long series of endless amusements and pleasures, to the neglect of sorely-needed church reform. True to his Medici heritage, Leo held lavish banquets, masques, dances, plays, and bullfights. The papal palace became a theater where even notoriously indecent and immoral plays were performed to the Pope’s delight. Leo also kept a pet elephant, which died when he gave it a laxative spiced with gold.

Leo worked to maintain the wealth and prestige of the Medici of Florence. Siena was a target of Florence’s expansion. When Leo ousted its ruler to install a crony instead, it infuriated Sienese Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci, who negotiated with allies to retake his home city. When Leo learned of it, he regarded it as an act of lese majeste. In April 1517, Petrucci and four other cardinals were accused of conspiring to poison Leo. Subjected to torture, Petrucci’s servant provided the prosecutors with evidence they were looking for in the form of correspondence between Petrucci and a doctor and divulged details of the plot. One of the cardinals confessed, probably also under torture.

On July 16, 1517, a Muslim executioner entered Petrucci’s cell at Castello Sant’ Angelo and strangled him to death (since it was improper for a Christian to execute a Prince of the Church). Leo had reserved for him the worst fate—the other accused were let go after being fined a staggering total of 250,000 ducats. A pope having a cardinal killed was unprecedented and shocked Rome.

Was there even a real conspiracy? Petrucci may have made some empty threats, but there is no solid evidence of an actual attempt to murder. Confessions made under torture obviously don’t count. In all likelihood, Leo seized the opportunity to put a malign interpretation on the evidence to eliminate a rival of Medici’s ambitions. While he was at it, why not also get rid of cardinals he didn’t like and replace them with more compliant ones? Leo profited immensely from the episode, raking in more cash to finance his luxuries and vices.

But the handwriting was on the wall in that fateful year of 1517. In Wittenberg, Germany, an Augustinian monk brooded over Leo’s excesses and the sorry state of the Church and felt it was time to act. Unknown to Leo, he would be the last pope of an undivided Christendom.[8]

2 Scandal of Indulgences

“As soon as a coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.” Dominican friar Johann Tetzel was a salesman, and this was the jingle he intoned as he traveled around Germany with his product: indulgences. For a small fee, people could buy a deceased loved one’s way out of the punishments of purgatory. They could also insure themselves from liability for any future sins they might commit for a price.

Indulgences were rare before the Renaissance, but as the Papacy became more materialistic, they became a big revenue-generating business. Nearly bankrupted by his frivolous lifestyle, Leo sorely needed income to push through his pet project, the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica. When his salesman Tetzel took his show to Wittenberg, he was confronted by the Augustinian monk Martin Luther.

He had long before preached against Church corruption and had embraced the doctrine of justification by faith. This was the last straw. “There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flies out of the purgatory immediately the money clinks in the bottom of the chest,” Luther protested. “The pope’s pardons are not able to remove the least venial of sins as far as their guilt is concerned.”

Luther posted 95 theses up for debate on the church door at Wittenberg. The floodgates had opened, and this challenge to Church authority would become a torrent—the Protestant Reformation. “Arise, O Lord… a wild boar has invaded Thy vineyard. Arise, O Peter, and consider the case of the Holy Roman Church,” Leo prayed. But Christian unity was beyond saving. At least Leo got his basilica.[9]

1 The Cardinal-Nephew

One day in 1548, 61-year-old Cardinal Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte (1487–1555) came upon a handsome teenage urchin fighting off a pet monkey in the marketplace of Parma. It must be some attraction for Fabian that led Giovanni to take the boy and put him under the care of his brother. Two years later, in 1550, the cardinal was elevated to the papacy as Julius III, and he officially adopted his illiterate 17-year-old ward and renamed him Innocenzo. Julius promptly made him the Cardinal-Nephew, making him responsible for all papal correspondence and the Vatican’s chief diplomatic and political agent.

Other cardinals detested Innocenzo, declaring him unfit for such an important post. Julius was adamant —Innocenzo would stay. At a time when the Protestant Reformation was sweeping Europe, Church reform was uppermost in their minds, and Julius’s decisions were further eroding its credibility. The Pope was clearly infatuated with the boy. Rumors swirled in the courts of Europe. Innocenzo was called Julius’s “Ganymede,” a reference to the Greek hero kidnapped by Zeus to be his cup-bearer on Olympus. A “Ganymede wearing the red hat on his head,” as poet Joachim du Bellay derisively wrote.

It was gossiped that Julius once awaited the boy’s arrival with the impatience of a lover for his mistress. The Venetian ambassador wrote that the pope “took him [Innocenzo] into his bedroom and into his own bed as if he were his own son or grandson.” Julius allegedly boasted of the Cardinal-Nephew’s prowess in bed. Julius made no attempt to counter the rumors.

One critic explicitly characterized him as “puerorum amoribus implicitus” (“entangled in love for boys”). Was it true? It may be significant that Villa Giulia, the pope’s private residence for which Julius nearly emptied the papal treasury, was decorated with naked cherubs and bacchanalian scenes.

Julius died in 1555, and Innocenzo, bereft of patron and protector, repeatedly got into trouble with his wild lifestyle and continued to be an embarrassment to the Church. He was imprisoned for double murder, released, and imprisoned again for rape. Innocenzo died despised and unmourned in 1577 and was buried in the del Monte family chapel near Julius.[10]