Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 TV Show Characters Who Carried The Entire Series on Their Backs

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Horror Movie Endings That Still Give Us Nightmares

Technology

Technology 10 Worrying Cases of Artificial Intelligence Gone Rogue

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Game-Changing Films That Shook Up the Superhero Genre

Music

Music 10 Metal Bands Who Accidentally Created Pop Hits

History

History Ten Totally Forgotten Deadly American Disasters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 TV Show Spin-Offs That Surpassed Their Original Series

Music

Music 10 Deceivingly Happy Songs That Hide Dark Meanings

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Summer Horror Movies Guaranteed to Give You Chills

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Superstitions People Actually Believe Are Real Facts

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 TV Show Characters Who Carried The Entire Series on Their Backs

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Horror Movie Endings That Still Give Us Nightmares

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Worrying Cases of Artificial Intelligence Gone Rogue

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Game-Changing Films That Shook Up the Superhero Genre

Music

Music 10 Metal Bands Who Accidentally Created Pop Hits

History

History Ten Totally Forgotten Deadly American Disasters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 TV Show Spin-Offs That Surpassed Their Original Series

Music

Music 10 Deceivingly Happy Songs That Hide Dark Meanings

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Summer Horror Movies Guaranteed to Give You Chills

General Knowledge

Random List

History

History Ten Totally Forgotten Deadly American Disasters

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

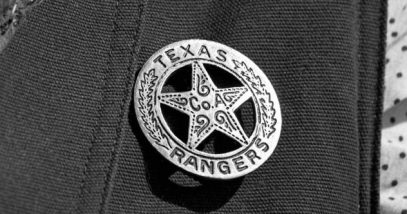

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of the Craziest Landlord-Tenant Disputes

History

History 10 Hilariously Strange Slang Terms Popular in the Old West

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Most Bizarre Casino Superstitions: Weird Luck Rituals Worldwide

Editor’s Picks

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Psychiatric Diagnoses Of Horror Villains And Their Victims

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Greatest Movie MacGuffins Of All Time

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Iconic Movie And TV Restaurants That Are Actually Real

Movies and TV

Movies and TV