Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Heroes Who Have Battled Evil Versions of Themselves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Ended Actors’ Marriages

Humans

Humans The 10 Strangest Records Set Traveling the U.S.

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Words Grammar Snobs Say Shouldn’t Exist but Do

Our World

Our World 10 Natural Disasters That Shocked the World in 2024

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unusual Items Credited with Saving People from Danger & Death

Music

Music 10 Famous Songs That Bands Refuse to Play Live

History

History 10 Instances Where One Vote Changed the World

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Reality TV Shows Sued by Their Participants

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Surprising Historical Origins of Christmas Traditions

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Heroes Who Have Battled Evil Versions of Themselves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Ended Actors’ Marriages

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans The 10 Strangest Records Set Traveling the U.S.

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Words Grammar Snobs Say Shouldn’t Exist but Do

Our World

Our World 10 Natural Disasters That Shocked the World in 2024

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unusual Items Credited with Saving People from Danger & Death

Music

Music 10 Famous Songs That Bands Refuse to Play Live

History

History 10 Instances Where One Vote Changed the World

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Reality TV Shows Sued by Their Participants

10 Important Expeditions Of Forgotten Explorers

Our understanding of the world would not be where it is today without the brave people who were willing to face the unknown and venture into the deepest, darkest regions of our planet. History is littered with these explorers, but few of them are remembered today for their efforts.

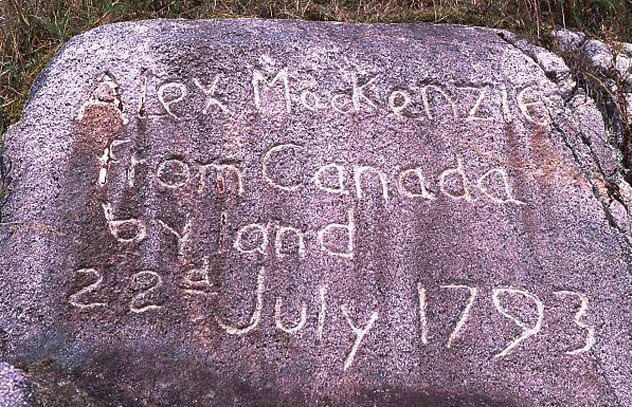

10 Alexander MacKenzie’s Transcontinental Trek

Alexander MacKenzie is remembered as a great explorer in Canada and his native Scotland, but he doesn’t get the global recognition that he deserves. He is not on the same level as some of his contemporaries, such as Lewis and Clark.

In 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase, Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark set out on an expedition to explore the new American territories, claim the Pacific Northwest for the US, and reach the Pacific Ocean.

They completed their transcontinental trek in 1806, ensuring their place in the history books. But Alexander MacKenzie had done the same thing more than a decade before them. In 1793, MacKenzie became the first European to cross North America. He could have done it even sooner if his first trip had been successful.

He originally set out for the Pacific Ocean in 1789 by following the largest river in Canada. MacKenzie hoped that it flowed into the Pacific, but the river actually went north into the Arctic Ocean. Even though the trip was a failure, that river is now named MacKenzie in his honor.

His second trip went much better. In 1792, MacKenzie set out from Fort Chipewyan in Alberta and followed the Peace River into the Rockies. After crossing the Great Divide, he followed the Bella Coola River and reached the Pacific Coast. There, he painted a simple message on a rock face that said: “Alex MacKenzie from Canada by land 22d July 1793.”

9 James Clark Ross’s Search For The Lost Expedition

The 19th-century British naval officer James Clark Ross continued the family tradition of exploration that was started by his uncle, Admiral John Ross. When James Ross was 18, he embarked on his first Arctic expedition with his uncle. It was followed by several more Arctic expeditions to find the Northwest Passage.

In 1831, he determined the position of the North Magnetic Pole, which was located at the time on the Boothia Peninsula. After numerous Arctic expeditions, Ross set his sights on the Antarctic. There, he discovered the Ross Sea (named in his honor) and Victoria Land.

Due to Ross’s experience in navigating the Arctic, he was offered the command of another expedition in 1845. This one was to chart the last stretch of unexplored Arctic coastline. Ross refused, and the opportunity went to fellow explorer John Franklin. However, Franklin’s journey ended in disaster and he was never heard from again.

Franklin’s lost expedition became the stuff of legends, and dozens of expeditions were led over the centuries to find it. It wasn’t until 2014 that the wreck of his ship was actually located.

In 1848, Ross commanded the first expedition in search of Franklin. However, heavy ice delayed his journey and winter caught up to him on Somerset Island. Ross set sail again in the summer and headed for Wellington Channel. But his path was blocked by ice again.

As a result, he was forced to return to England. Little did he know that he would have found the site of Franklin’s doomed encampment on Beechey Island inside the channel.

8 Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s Circumnavigation

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville was an 18th-century French admiral. He rose to prominence by fighting in the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolutionary War. Once peace was declared, Bougainville left the navy in 1763 and indulged his passion for exploring. He set out to colonize the Iles Malouines, now known as the Falkland Islands.

Even though Bougainville was successful, his new settlement angered Spain due to its location near Spanish trading routes. To maintain the delicate relationship between the two countries, the French government sold the colony to Spain in 1764.

Undeterred, Bougainville set his sights on a new goal—becoming the first Frenchman to sail around the world. Supported by King Louis XV, Bougainville was to cross the Strait of Magellan to the East Indies and reach China. He was also free to take possession of any new land that he came across in the name of France.

In 1766, Bougainville left France with two ships and 330 men. His crew included astronomer Pierre-Antoine Veron and naturalist Philibert Commercon. They visited islands such as Tahiti, Samoa, and Bougainville Island in Papua New Guinea, which he named after himself. He also claimed Tahiti for France, only to learn later that British explorer Samuel Wallis had discovered Tahiti shortly before him.

Bougainville completed his journey in March 1769. Although rather uneventful, he was responsible for the first French circumnavigation of the globe. More impressively, he only lost seven men. Bougainville published his successful account Voyage autour du monde in 1771.

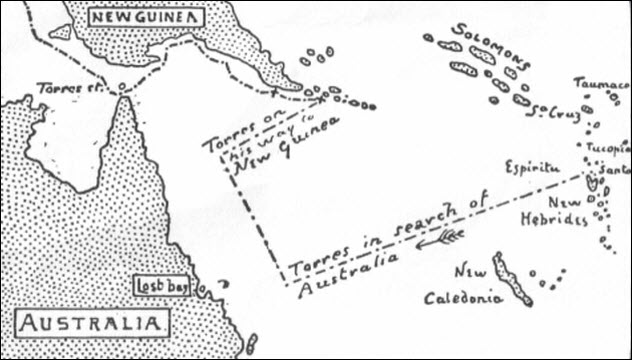

7 Luis Vaz de Torres’s Search For Terra Australis

Since antiquity, the idea of a great southern continent has persisted. For some, there was a belief that the northern landmass must be balanced by land of similar size in the southern hemisphere. This undiscovered land, eventually known as Terra Australis, became a Holy Grail for explorers during the golden age of sailing.

Many expeditions tried and failed to find the “Great South Land.” A notable one was led by Pedro Fernandes de Queiros. After several successful voyages in the Pacific, Queiros convinced the Spanish king and the Pope to support his search for Terra Australis. In 1605, assisted by second-in-command Luis Vaz de Torres, Queiros left with two ships and a launch.

He found a chain of islands and settled on the largest one, believing it to be part of the continent. He named it La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. But he was wrong. The islands actually formed the nation now known as Vanuatu.

After a failed attempt to establish a settlement, Queiros’s ship was separated from the others during a storm. Unable or unwilling to return, he sailed to South America. Torres, believing that Queiros was lost at sea or killed in a mutiny, assumed leadership of the expedition.

Torres set sail for Manila. On his way there, he passed through the Torres Strait (named in his honor) that separated New Guinea from Australia. From his position, Torres probably saw Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost point of continental Australia, but dismissed it as just another island.

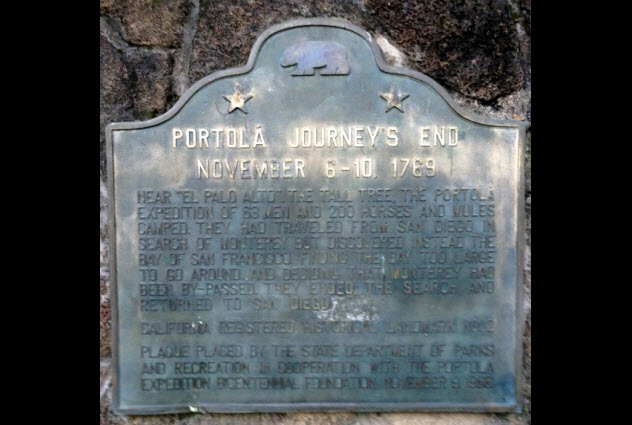

6 Gaspar de Portola’s Californication

The Spanish Empire first set foot on the territory of California in the mid-16th century. Over the following decades, Spanish explorers surveyed the coast of California but never went far inland. Settling this new land was not a priority when compared to securing Spain’s dominance in Europe. For over 150 years, Spain did little more than establish a few Jesuit missions along the Baja California peninsula.

Then, in 1767, the suppression of the Jesuits started in the Spanish Empire. King Carlos III ordered an expedition to travel to California and replace the Jesuits with Franciscan missionaries. The man who led this expedition was a dragoon captain named Gaspar de Portola. He and his team were the first Europeans to explore inland California. In 1769, Portola founded and became governor of the New Spain province of Alta California.

The Spanish king feared that other European powers would be interested in settling along the Californian coast, so he ordered Portola to keep exploring the territory and build new outposts. From past explorers, Portola knew of several bays in the area. He traveled to them and founded Monterey and San Diego.

Although Monterey Bay was Portola’s destination, he initially went right past it, not recognizing it from land. His expedition traveled north until they reached San Francisco Bay. Realizing his mistake, Portola returned to San Diego in January 1770. His accidental discovery of San Francisco Bay is still marked by a monument that has been designated a historical landmark.

5 George Vancouver’s North American Expedition

George Vancouver was an 18th-century English navigator who undertook one of the longest, most difficult surveys in history. Primarily, it charted the Pacific Coast of North America.

Initially, Vancouver was assigned as second-in-command to Captain Henry Roberts. However, in 1789, word reached London of the Nootka Sound incident—an event in which Spain had seized British trade ships that were supposedly trespassing in Spanish waters.

The expedition was postponed as England prepared to go to war. After Spain relented and paid restitution to England, the expedition was on again. By this time, however, Roberts had been assigned to the West Indies. So Vancouver was put in charge.

The Vancouver Expedition set off in 1791. Before reaching North America, it surveyed coastlines in Australia, New Zealand, Tenerife, and Cape Town. Vancouver entered the North American mainland through the Strait of Juan de Fuca near the city that now shares his name.

Vancouver was to survey the coast all the way to Cook Inlet in Alaska. He didn’t finish until 1794, but his survey became known for the detail in which every inlet and outlet was charted.

Along the way, Vancouver described and named numerous geographical landmarks—including Puget Sound after his ship’s lieutenant, Peter Puget. Furthermore, Mount St. Helens, Mount Hood, Mount Rainier, and Mount Baker were all named after British officers who were Vancouver’s friends.

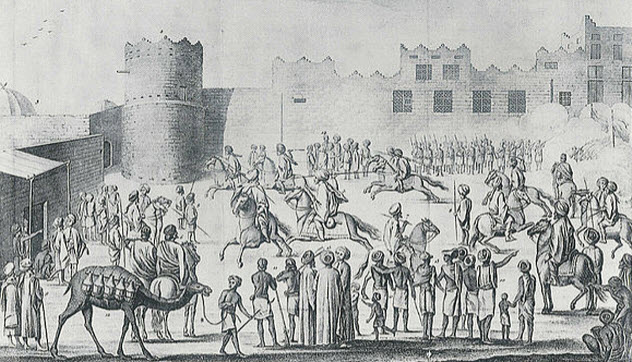

4 Carsten Niebuhr’s Arabian Journey

Europe’s knowledge of distant lands increased dramatically due to the efforts of maritime nations establishing trade routes with new markets. There came a point when these nations started craving not only practical knowledge but also theoretical knowledge.

Under the auspices of King Frederik V, a team of six set off from Copenhagen in January 1761 and headed for Alexandria. The initial goal was to learn the Arabic language so as to better translate the Old Testament.

Originally, just one man was supposed to travel to Yemen and purchase manuscripts, but interest in the expedition kept growing. Eventually, the team included a philologist, a natural scientist, a cartographer, a physician, an artist, and an orderly.

The Danish Arabia Expedition gained infamy after just one member made it back to Denmark alive. Carsten Niebuhr, the cartographer, returned to Copenhagen in November 1767. He credited his survival to his ability to adapt to his circumstances. Niebuhr’s companions had tried to dress, drink, and eat the “European way,” which caused them to fall gravely ill.

On his journey, Niebuhr had visited Egypt, Yemen, India, Persia, Cyprus, Palestine, and the Ottoman Empire. He also went to the ruins of ancient cities like Persepolis and Babylon and made copies of the cuneiform inscriptions.

These copies were later instrumental in the founding of Assyriology, the study of ancient Mesopotamia. Historically, all of his maps, charts, and town plans constituted one of the greatest single contributions to the cartography of the Middle East.

3 Nobu Shirase’s Antarctic Expedition

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration is known for many European expeditions that risked everything to explore the frozen lands of the Antarctic. But interest in the Antarctic wasn’t restricted to Europe. In 1910, Japan organized the first non-European expedition to the continent.

The expedition was led by Nobu Shirase, a Japanese army lieutenant. His plans were viewed with skepticism by the Japanese public, and Shirase found it difficult to obtain the support that he needed. On December 1, 1910, he left Tokyo in a small 30-meter (100 ft) vessel in front of a modest, uninterested crowd.

Shirase’s first attempt was hindered by terrible weather. He was forced to turn back and head to Australia for ship repairs while he raised more funds from Japan. In Sydney, the Japanese expedition received a hostile welcome because people thought they might be spies.

It wasn’t until Sir Edgeworth David intervened that public opinion shifted in favor of the Japanese. David was part of the Nimrod Expedition and the first team to reach the South Magnetic Pole. He vouched for the Japanese explorers and shared his considerable knowledge. When Shirase left, he gifted David with a 17th-century sword that had been made by a master swordsmith.

Shirase’s second attempt went better. Although he was still unable to reach the South Pole, he was the first person to explore King Edward VII Land, a peninsula on the Ross Ice Shelf. It had been previously discovered and named by Robert Scott, but nobody had set foot on it before Nobu. The western coast is called Shirase Coast in his honor.

2 Alessandro Malaspina’s Scientific Expedition

During the Age of Enlightenment, Italian-born Spanish officer Alessandro Malaspina went to the Spanish government with an ambitious proposal—a scientific expedition to explore and chart most of Spain’s Asian and American possessions. Malaspina was an experienced explorer who had circumnavigated the world in 1788.

King Charles III was a supporter of science, so he granted Malaspina’s request. Malaspina and fellow explorer Jose de Bustamante y Guerra sailed from Cadiz in 1789 in two corvettes.

The expedition initially crossed the Atlantic Ocean and touched down in Montevideo. From there, Malaspina explored the coasts of South America before sailing to the Falkland Islands. Then he crossed to the Pacific Ocean through Cape Horn and began exploring the Pacific Coast. He started from Chile and ended in Mexico.

By the time Malaspina reached Mexico, Charles IV had succeeded his father. Charles IV gave the explorer new orders to chart the recently discovered Northeast Passage. So Malaspina changed course and went north to Alaska. Afterward, he also visited the Philippines, New Zealand, Australia, and Tonga.

The expedition lasted five years and gathered a treasure trove of information due to the astronomers, cartographers, and naturalists on board. However, most of that information remained hidden for centuries. In fact, some of it was lost forever.

That’s because Malaspina disagreed with the new political regime and was part of a conspiracy to overthrow the prime minister. He was initially imprisoned as a traitor, but he was later exiled. It was 200 years before the bulk of his journals were published.

1 Francisco Balmis’s Smallpox Mission

After the Spanish conquest of the Americas, smallpox became one of the major afflictions that devastated the New World. In 1798, a major advancement took place when Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine.

A few years later, Francisco Xavier de Balmis, the Spanish royal physician, thought that the vaccine should be used in the colonies to contain smallpox outbreaks. After convincing King Charles IV to fund an expedition, he set off on the world’s first immunization campaign in 1803.

The main problem was finding a way to keep the vaccine viable over such long distances. The solution involved passing it arm to arm between orphans. Twenty-two orphan boys between eight and 10 were brought along and given the vaccine successively. The fluid from their skin vesicles was preserved on glass slides that were sealed with paraffin and kept in a vacuum.

The expedition first took Balmis to the Canary Islands and then to Puerto Rico. In Puerto Rico, he was surprised to find that the island had already obtained the vaccine from the Virgin Islands. Balmis worked with the governor to establish a central vaccination board, a method that he successfully implemented on all future stops.

To cover more ground, the expedition split in two. It reached Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Cuba, and Mexico. Based on its success, Charles IV ordered the campaign to continue in the Philippines.

Afterward, Balmis headed for China, but a severe storm killed many of the ship’s crew on the way. That was the last major stop before Balmis returned to Spain. The Balmis Expedition was a huge success, and Edward Jenner hailed it as history’s greatest philanthropy.

Radu is into science and weird history. Say hi on Twitter, or check out his website.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)