Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Ways The Maori Made Life Hell For The New Zealand Colonials

No tribe could stand against the might of the colonial British Empire. In the era of colonialism, when the British Empire swept through every corner of the globe, no one could stop them. Few made them fight as hard, though, as the Maori of New Zealand.

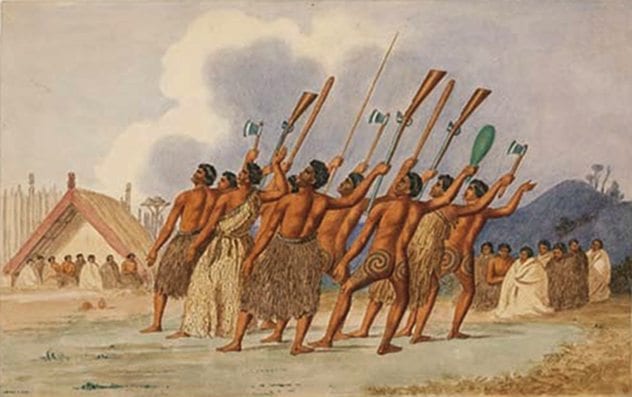

The Maori, before colonialism, were brutal warriors. They were cannibals. They were head hunters and slavers. Above all, they believed in “utu”—that every kind and cruel deed should be repaid in kind. And, when the British colonialists took over New Zealand, they were ferocious enough to make sure they paid for it.

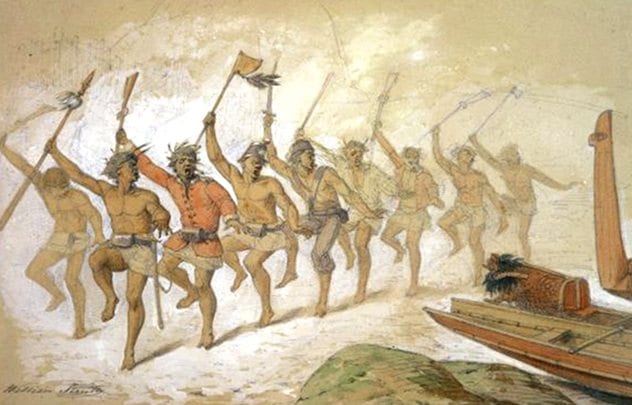

10First Contact with the Maori Ended in Four European Deaths

When the Maori met their first Europeans, they did not shake hands and welcome them in. Right from the very start, there was bloodshed.

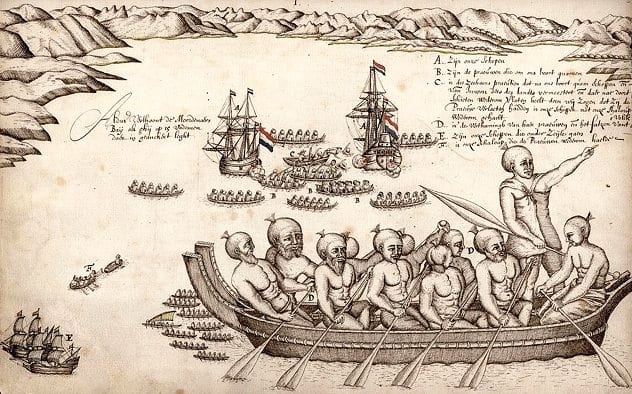

First contact happened in 1642, when Abel Janszoon Tasman and his crew became the first Europeans to meet the Maori. The Maori, though, saw them first. As Tasman sailed into the Golden Bay, signal fires lit up along the shore. The Maori were letting one another know that a strange ship was approaching and to get ready for the worst.

On their first meeting, the Maori canoed out toward Tasman’s boats, blowing shell war trumpets and trying to scare the Europeans away. Tasman responded with cannons. The Maori fled—but now they had no doubts. These were definitely people to fear.

The next day, Maori canoes came out toward the boats again. Tasman’s men figured it was a friendly gesture, inviting them to come to shore—until the Maori started ramming their boats. One Maori clubbed a sailor in the back of the head with a pike and knocked him overboard. Then the others attacked—and killed four men before Tasman’s men could get away.

Tasman named the area “Murderers Bay”. This, he said, “must teach us to consider the inhabitants of the country as enemies.”

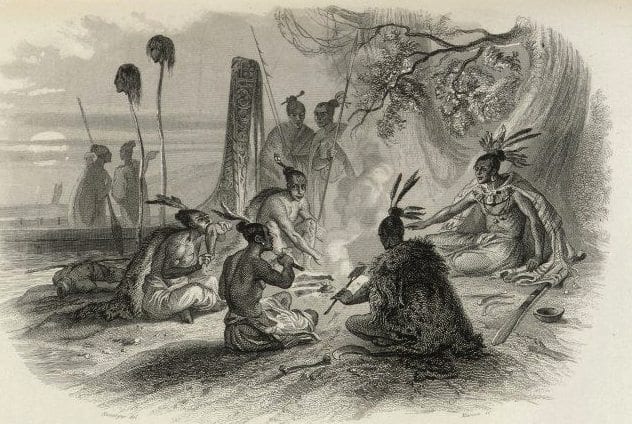

9A Tribe Cannibalized James Cook’s Crew

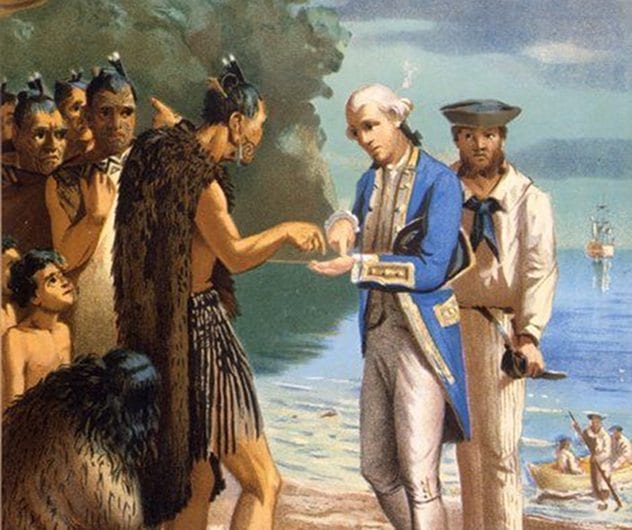

For the next hundred years, Europeans stayed away from New Zealand. The Maori were left alone—until James Cook arrived.

At first, Cook’s men had a rocky but relatively peaceful relationship with the Maori. They had some problems, though. One man, Jack Rowe, had angered some of the Maori when he tried to kidnap a few of their men—and the Maori, it seems, were getting ready for revenge.

On December 17, 1773, Jack Rowe led an expedition ashore to collect food. They never came back. The men waited for them, growing more and more worried as time passed. In the morning, a second group led by James Burney went ashore to find them.

Soon, they found a Maori canoe and the remains of what they hoped was a dog. When Burney came in for a closer look, though, he found a human hand among the torn flesh. It was tattooed “TH”—the initials of Thomas Hill, one of the men who had gone ashore.

Burney and his men ran for their lives. When they made it to the beach, hundreds of Maori ran out to taunt them. Burney looked back. The Maori were roasting the pieces of Rowe’s dismembered body over a fire. They were devouring the flesh of Rowe and his men and feeding their entrails to the dogs.

8The Boyd Massacre

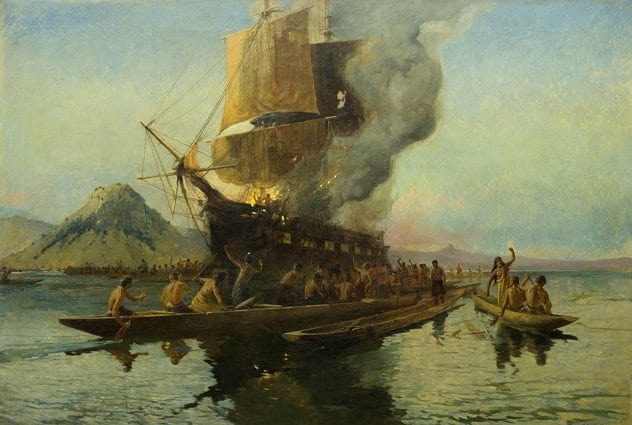

Europeans started colonizing New Zealand, despite the threat the Maori posed. Soon the country had towns and ports filled with white faces. The encounters, here, became less hostile, and some Maori began to trade with the Europeans and even work on European ships.

One of those Maori was Te Ara. He boarded a ship called The Boyd, believing he would be treated with all the honors due to the son of a chief. The captain, though, did not care whose son he was. He expected Te Ara to work—and, when Te Ara refused, he had him flogged.

Te Ara told his tribe what happened, and they were furious. They waited until the captain went to shore, then jumped out on him and his party. They murdered every person there and cannibalized their bodies.

Then they put on their clothes and used them to get onto The Boyd. They killed nearly every person on board, murdering 66 people in all. Before they were allowed to die, many had to watch while the Maori dismembered their friends’ bodies. Only four people were spared: three children and a mother.

New Zealand, after that, got a new name—the “Cannibal Isles.” Travel guides across Europe listed it with a warning: “Avoid if at all possible”.

7Introducing Muskets to the Maori Led to More Than 18,000 Deaths

Not everyone avoided the Maori. Some people actually joined them. Runaway sailors and escaped convicts from Australia joined Maori tribes and married Maori women. They were known as the Pakeha Maori—white men living Maori lives.

With the help of the Pakeha Maori, the Maori were able to get muskets—a moment that changed their history ever. Maori tribes had fought one another for years, but muskets meant a total change in that balance of power.

The Ngapuhi tribe got muskets first, and started using them to dominate their enemies. Other Maori responded by getting their own, and, for the next 40 years, New Zealand erupted in the most vicious tribal warfare it had ever seen.

By the end, a massive chunk of the Maori population was dead. There were only about 100,000 Maori in 1800. By 1845, by conservative estimates, 18,000 people had died—although others put that number twice as high. By some estimates, up to half of their population was wiped out.

The British were getting nervous. Open trade, they now believed, was very dangerous. From here on in, the British started changing how they dealt with the Maori.

6The Wairau Affray

In 1840, the British signed a treaty with 540 Maori chiefs: the Treaty of Waitangi. This gave the British sovereignty over New Zealand. In exchange, the Maori kept the right to buy and sell land, and had the rights and privileges of British citizens.

Some of the Maori who signed it did not totally understand what it meant. They understood, though, that they had the right to their land—and they were not about to give it up.

The first fight happened in Wairau. Some British settlers purchased land in the Wairau Valley and realized they did not have as much as they wanted—so they started surveying some land that the Maori had not sold them. The Maori were not okay with this. They burned the surveyor’s equipment down and sent them back to their ships.

The surveyors tried to charge two Maori chiefs with arson and sent in a force to arrest them. The Maori, though, were ready for them. Their warriors refused to move—and, after the first shot was fired, they fought back. By the end, 22 Europeans were dead, and the rest chased away.

This, though, was only the first fight of many. The British would keep encroaching on Maori land, and they would keep pushing back. For the next sixty years, the history of New Zealand was filled with land conflicts and bloodshed.

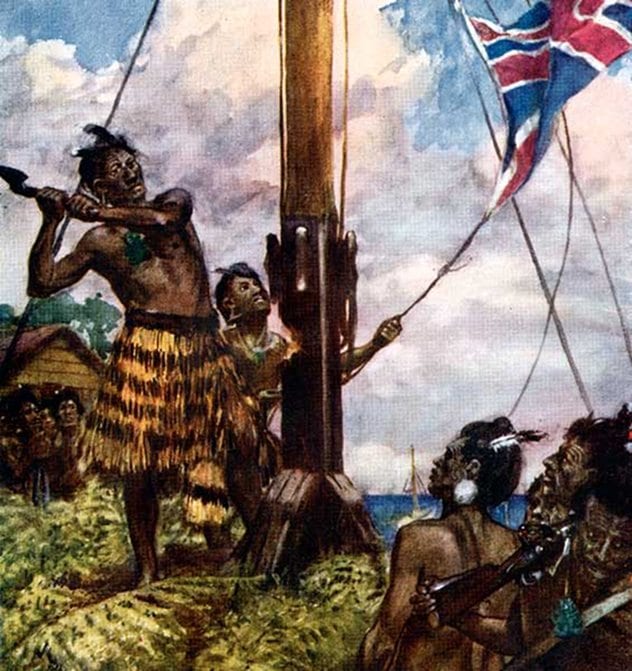

5The Flagstaff War

In 1842, a Maori man named Maketu was tried and hung for murder. He had been working for a European who he felt mistreated him—and he dealt with it by going to her home and slaughtering her and her entire family.

One Maori chief, Hone Heke, was furious. Maketu had been tried under British law. This was further proof that the Maori no longer had control over their own country. They were paying taxes and tariffs for the first time in their lives, and they were subject to foreign courts. Hone Heke decided he would no longer live under British rule.

He had his men cut down a flagpole that waved the Union Jack. When the British put it back up, he cut it down again—and again. The British tried to put it back up three times, and Hone Heke cut it down every time. “God made this country for us. It cannot be sliced,” he wrote to the British forces. “Return to your own country, which was made by God for you.”

The two sides fought to a standstill, with no clear winner. When the fighting ended, though, the Union Jack still laid trampled in the dirt.

4The Massacre of the Gilfillan Family

A few years later, a British sailor named H. E. Crozier shot a Maori man named Hapurona Ngarangi in the face—something he maintained was an accident. His crewmates managed to treat Ngarangi and keep him alive, but Ngarangi’s tribe was not satisfied. They wanted Crozier dead.

The British refused, but Ngarangi’s tribe demanded “utu”. They could not leave a bad deed unpunished—they needed vengeance. If the British would not give them Crozier, they would carry out their revenge on the nearest settler they could find.

They went to the home of a painter named John Gilfillan and massacred his family. John assumed they were after him and ran out, expecting the Maori to chase him, but they let him go. Ignoring him, they slaughtered his wife and children and burned his house to the ground.

The British arrested the men responsible and had them executed—but the Maori would not accept that, either. Soon, a Maori tribe had the town under siege. Another war had broken out.

3The Horrible Death of Carl Sylvius Volkner

A new religion was starting in New Zealand: Pai Marire. It was a combination of Christianity and Maori beliefs, founded by a prophet named Te Ua Huamene. They would prove to be one of the biggest problems the British faced.

When fighting broke out between the Pai Marire and other Maori tribes, one German missionary refused to leave. Carl Sylvius Volkner was warned that he would die if he stayed where he was, but he was determined to stay and spread the gospel.

The Pai Marire did not appreciate it. They started to suspect that the reason Volkner was sticking around was because he was a spy, and so they got rid of him—in one of the most brutal ways in history.

One of Huamene’s disciples, Kereopa Te Rau, had Volkner taken prisoner and executed. Before he died, Volkner was allowed to kneel down and pray. Then he stood up, shook hands with his killers and told them, “I am ready.”

After he was dead, Kereope Te Rau hacked off Volkner’s head. He grabbed his decapitated head, walked into the church, and delivered a sermon with Volkner’s head on the pulpit. At the climax of his speech, before his followers, he gouged Volkner’s eyes out and swallowed them.

2The Massacre at Poverty Bay

Not all Maori fought the British. Some became loyal to, and fought side-by-side their colonizers, beating down Maori rebellions. Te Kooti was one of these loyalists—until the British became paranoid he might be a spy and threw him in prison.

Locked in a jail cell on the Chatham Islands, Te Kooti had a change of heart. He spent three years in prison before he broke out. He freed 298 other Maori prisoners, seized a ship, and sailed off, landing in Poverty Bay.

There, they were confronted by the town magistrate, Reginald Biggs. Te Kooti told Biggs they just wanted to pass through peacefully. Biggs demanded they give up their weapons. Te Kooti refused—and things escalated.

That night, Te Kooti and his men broke into Bigg’s home. They gunned him down and stabbed him with their bayonets, then killed his wife and his newborn baby. Then they ran through the town, slaughtering every person they could find. Before the massacre was through, 51 people had died.

Te Kooti, it was clear, was no longer a loyalist. When the massacre was over, he waged one of the biggest wars New Zealand would see.

1Riwha Titokowaru’s Guerilla Army of Cannibals

At first, Riwha Titokowaru pushed for peace with the British—but when he went to war, he went at them hard.

He brought back the old Maori tactics of war to strike fear in the hearts of the British. His men would cut out the heart of the first man they killed and cannibalize the others. “I have begun to eat the flesh of the white man,” he told the world. “I have eaten him like the flesh of the cow, cooked in a pot.”

He was trying to terrify the British—and it worked. Titokowaru’s campaign was so vicious that the British nearly gave up. One battle against Titokowaru was called “the most serious and complete defeat ever experienced by the colonial forces.”

“The small and utterly disorganised force here might any night be cut up and cooked by Titokowaru,” one man wrote. “Unless something is done and done quickly, we had all better clear out.”

In time, though, Titokowaru’s onslaught ended. The British did not stop him—he had an affair with a subordinate’s wife and lost the respect of his men. They abandoned his fort and gave up the fight.

The wars raged on and thousands more died—but, by the 1900s, the Maori had been pushed to the fringes of the country. The last insurrections were quelled. The Maori could not keep their land from being colonized—but they made the British go through hell to get it.

Mark Oliver is a regular contributor to Listverse. He writing also appears on a number of other sites, including The Onion’s StarWipe and Cracked.com. [His website] (www.mark-oliver.com) is regularly updated with everything he writes.