Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Great Hoaxes of the 19th Century

Hoaxes aren’t just for the modern age—a couple of hundred years ago people seemed to make an art of it. From carnivorous trees to firearm conception, from gigantic vegetables to ancient old ladies, when it comes to hoaxes, the 19th century might just take the prize for greatest wind-ups ever.

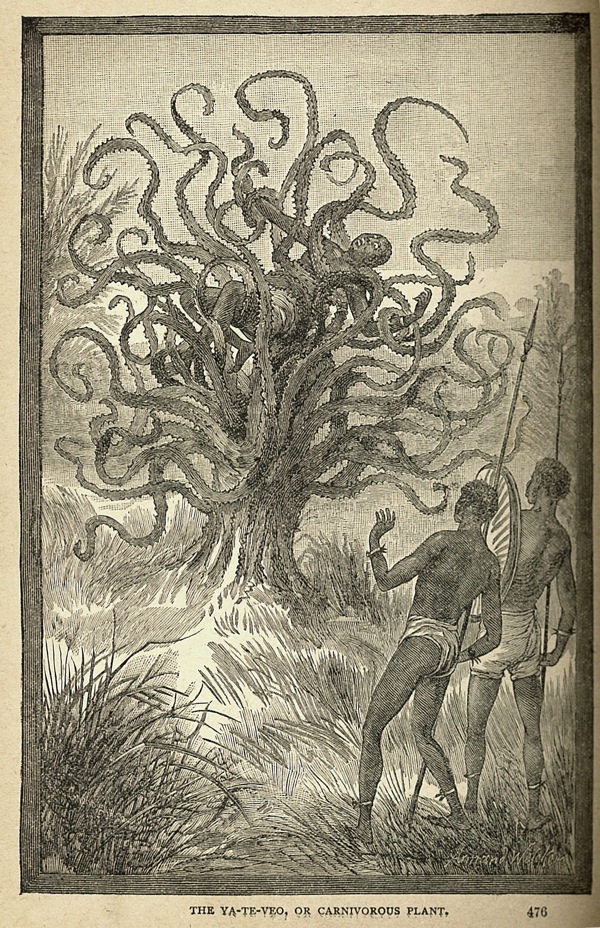

The Hoax: The Man-eating tree of Madagascar

A gigantic pineapple, seemingly made of some kind of natural metal, with an aura of human skulls at its base—this is one tree you wouldn’t want to climb. The tree in question first appeared in a letter sent to the New York World newspaper in April, 1874. It was discovered by German traveller Karl Leche whilst exploring what was then the little known island of Madagascar. The tree made headlines the world over when Leche described in some grizzly detail how he had watched it devour a young woman.

The account described Leche and some other European travelers being taken to a clearing by a tribe called the Mkodos. On arriving, a female member of the tribe was ordered to climb the tree and sup from a bowl of white liquid which could be found at this devilish plant’s core. She drank from the bowl and was suddenly gripped by a trance like state. Seconds later she was snapped up by the trees large tentacle-like leaves and disappeared into the folds of the fiendish foliage.

Leche’s account ended by saying that some days later he returned to the scene only to find a shiny white human skull at its base. Being 21st century folk—growing up with The Day of the Triffids as bedtime reading—we would have sniffed out the lies in a jiffy. But this was in the 1800s and parts of the world were yet to be fully explored. It took a whooping fourteen years before the editor of the New York World, Edmund Spencer, came clean. He often made up sensationalist stories to boost sales, but even his confession did little to dampen people’s thirst. Well into the 20th century eminent botanists and professors were still searching for the man-eating tree of Madagascar.

The Hoax: Penis Cult—exalted by French priest

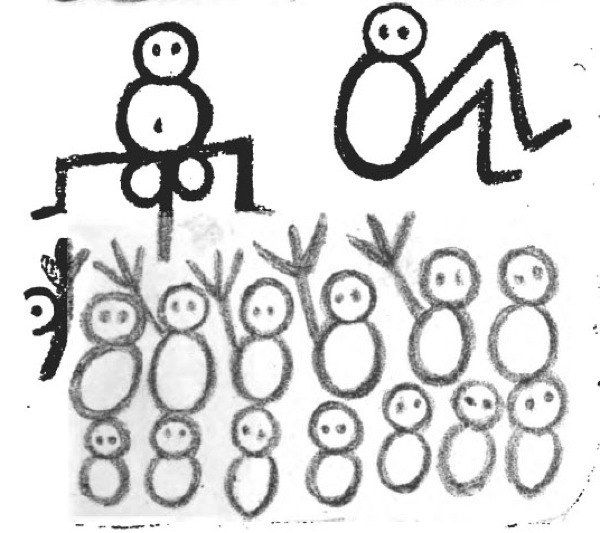

The last person you would expect to be promoting phallic drawings is your parish priest . . . unless his name is Emmanuel Domenech that is. A prolific traveller and respected authority on Mexico and the American South, when the Frenchman returned to his native shores in the 1850s, a librarian at the Arsenal library in Paris asked him to look at a book which had been found in the archives. It was a book depicting stickmen with what seemed to be immense phalluses.

After some consideration Domenech believed the document to be the work of a Native American tribe and he named it, Book of the Savages. So taken with this historical document Domenech even managed to convince the French government to pay for its publication. Manuscript pictographique Americain, published in 1860 with a forward by Domenech exploring his theories on the cult of the phallus. In his enthusiasms, he openly admitted to not understanding many of the Native American symbols. Whoops.

When copies of the books reached Germany, scholars and layman alike recognized the symbols as German words, albeit written by a child’s hand. Domenech evidently did not know German. One newspaper in particular even went as far as saying that the book must have been the work of a schoolboy and had somehow found its ways into the depths of the Parisian library. A theory scoffed at by Domenech. At least until the newspaper reported that one word which Domenech had loosely translated as ‘lightening or divine wrath’ was in actual fact the German word for sausage.

The Hoax: Mark Twain and his Petrified Man

Mark Twain is often praised as the man who wrote the great American novel. But long before he was penning the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he was a small time scribe for a local newspaper. Presumably bored with the day to day monotony of his life he decided to play a little prank on his unsuspecting readers. Writing under a pseudonym—of which Twain had many over the years—he published a piece in the Territorial Enterprise on October 4, 1862 entitled The Petrified Man.

The short blurb of news described the discovery of a one hundred year old stony mummy with a wooden leg, pensive attitude, and a cause of death by protracted exposure. You may notice that the description is close to gobbledegook, which was Twain’s very intention. What he didn’t intend was the coverage the piece garnered. Originally meant as a slight jibe at the newspapers of the time’s obsession with petrifaction, Twain expected his practical joke to get found out. But before he knew it, people were reading about The Petrified Man as far away as London.

The Hoax: The letter decreeing the sun will destroy the earth

Global Warming. Polar bears floating off on melting icebergs; the world going up in flames, all that jazz. We tend to think of it as a modern phenomenon, correct? But the red-hot inferno that awaits our planet was on people’s minds well over a hundred years a go. Well, one person’s mind in particular—and he wasn’t being entirely honest about his fears either.

In 1874 the Kansas City Times received a letter under the heading A Scientific Sensation from a charming fellow called J. B. Legendre who claimed to be passing the letter on from an anonymous man of science. The letter disclosed something of “agonizing importance” to the human race which had been discovered by Italian astronomer Giovanni Donati. Donati had been measuring the earth’s distance from the sun and he had found that we were moving closer to everybody’s favorite beach ball in the sky.

But what was causing this massive shift towards our nearest and dearest star? Donati had been making his calculations ever since the first transatlantic telegraph cable was laid in 1858 and with each subsequent cable laid he had noticed a dramatic decrease in the distance between planet and sun. The cables, he claimed, were acting as gigantic electromagnets pulling us towards the star. He even went as far as predicting Europe would go tropical by 1886 and that before the year 1900 we’d all be burned in our bed by the searing heat of the sun.

You can’t help but think that Donati really must have been a ball at dinner parties. Donati died in 1873 and despite the fact that the story—apart from the cables—is completely made up, Donati himself was a real astronomer (he even has a comet named after him). The hoax hung about in newspapers for a few months but nobody ever really took it seriously. Yet still, it must go down as one of the most bizarre predictions of all time.

The Hoax: The man who invented solar armor and died in the process

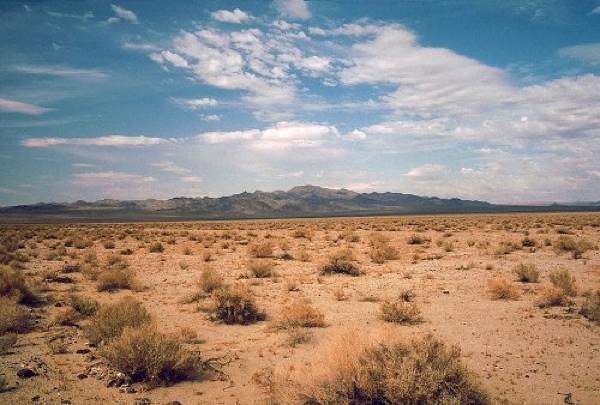

It may sound like something out of Flash Gordon and quite frankly it easily could be. Designed to reflect the heat of the sun, this high tech armor was said to reduce the wearer’s temperature despite the hostile weather outside of the suit. Of course it was the fictional invention of writer Dan de Quille and—as with all hoaxes—the suit alone wasn’t a fib far enough. There had to be some kind of tragedy or sensation tied to it. Cue, man freezing to death wearing said solar armor in the middle of the Nevada desert. A story that made its way from San Francisco to New York to London within a matter of months in 1874. Although it should be noted that The Daily Telegraph questioned the validity of the story . . . although, on the other hand, they also ran with it.

The Hoax: The girl who got pregnant by a bullet

How, oh how, did the editors of The American Medical Weekly not think that this one might be a wind up? Let’s paint it in its simplest form: a bullet shoots through a man’s scrotum, passing, and severing a testicle in the process before lodging itself in a woman and impregnating her with the fruits of his reduced-by-one loins. The article ran with the headline: “Attention Gynaecologists!”

The case study went on to say that the child was born with an enlarged scrotum and when the doctor executed a thorough examination of the boy he found a bullet wedged inside his nether regions. Now there’s a trick we’d all like to see David Blaine perform. All is not what it seems with this tale however. The editor of the journal did indeed spot that the case study was a fake and although the letter was sent in anonymously, upon recognizing the handwriting of a frequent, and sometimes cocky, correspondent he published the name, and the article, to get one over his would-be wind up merchant.

The stain on the joker’s character remains, as taking pride of place at the top of Dr. LeGrand G. Capers Wikipedia page there lies the immortal lines: “American physician, best known for his 1874 spurious case report of bullet-mediated impregnation of a young woman.”

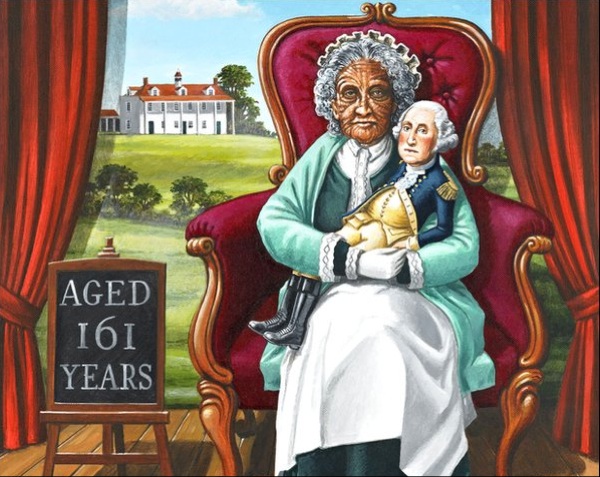

The Hoax: The 161-year-old nurse to George Washington

Some hoaxes seem to serve no other purpose than to baffle and amuse. Others, however, seem hell-bent on the malevolent manipulation of not only those being tricked, but those being used within the hoax itself—and all for a few measly coins. The case of Joice Heth is one such example. Joice Heth was an African-American slave who, according to some, had reached the stately age of 161 years old. At this milestone, her owner decided to sell her to a promoter—informing him that she was once a nurse to Founding Father of the United States George Washington.

In fact, if you believed his chat, she was the first person to dress the future president. A few promoters down the line and Heth was passed on to P. T. Barnum. A devious and ruthless man, Barnum pushed Heth, now invalided and all-but blind, into a make or break schedule, exhibiting her for seven whole months on the trot. The exposure paid off, and once the media’s ears were pricked the show took off, earning Barnum a king’s ransom. Heth died in 1836. The end of it you might think? Nope.

Sensing another killing of the monetary kind, Barnum, allegedly to sway the naysayers, set up a live autopsy to prove Heth really was as old as he had said she was. Barnum charged fifty cents for admission and packed fifteen hundred plus spectators in to New York’s City Saloon. Rather laughably the doctor performing the procedure insisted the body could be no older than 80 years, yet Barnum still clung to his lies, insisting Heth was alive and well, touring the stages of Europe to much acclaim. Fast-forward a few years and Barnum was chancing his arm at becoming a respected politician; and only then did he admit to the masquerade. Too little too late, for Barnum will always be remembered as one of the most infamous manipulators the world has ever seen.

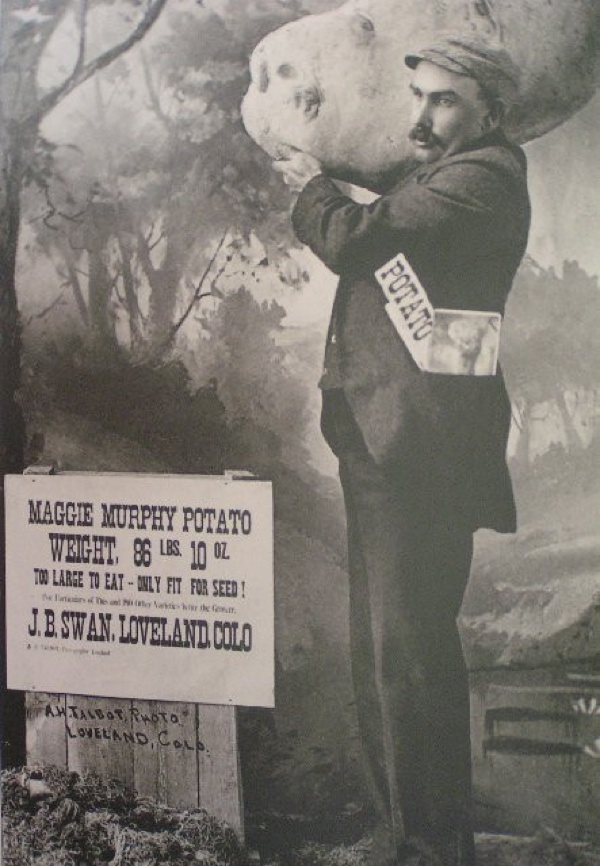

The Hoax: The mammoth potato

Joseph B. Swan loved his potatoes. Living on a farm outside Loveland, Colorado, he produced some thousands of the beauties week in week out. But he wasn’t making much money. Up steps close friend W. L. Thorndyke, editor of the Loveland Reporter. Together they hatch a plan to produce a fake photograph of a potato weighing 86 lbs 10 oz (39 kg). An 1895 Photoshop job involved photographing the potato, blowing it up on to a sheet, pinning it on to a board and taking a new photo with the fake potato.

When the editors of Scientific American took the photograph for authentic and published it alongside a full account of the potatoes dimensions, the hoax, which was meant for local eyes only, soon went national. Once the journal realized their error they retracted the story but by now Swan was inundated with requests for private viewings of the potato. Eventually Swan said the potato had been stolen but still it wasn’t the end of the matter and for several years after the incident he was still receiving requests for seeds. There was even a play made about the story.

The Hoax: The Orgueil Meteorites and the seeds of aliens

From UFOs to Sigourney Weaver’s maternal performance in the Alien franchise, the human race has a bit of an obsession when it comes to extra terrestrials and this is no new thing. In May, 1864 a meteor shower hit the south of France. Named Orgueil the meteor fragments were gathered up and transported to the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle in Montauban where two of the pieces were kept sealed in a jar and all the others were sent on to the further reaches of the continent. Jump forward to 1966 and the meteorites were subjected to a check up, some one hundred years after their discovery.

Researcher Bart Nag was amazed to see what he believed to be ‘microfossils’ – ultimately nothing short of proof of life on other planets. When the find was examined by others the validity of the microfossils, revealed to be the seeds of plants, was brought into question. Critics suggested the seeds had been planted within the meteorite once it had landed on Earth. The fact the seeds belonged to a plant native to Southern France, and the outer casing of the meteor was pasted with a crude coat of glue put the case to bed. However, to this day, the debate rattles on and some still believe the Orgueil Meteorites may hold the key to the question we all really want know: is there anybody out there?

The Hoax: The monkey’s backside turned into creature of folklore

Charles Waterton was in short, somewhat of a nutter. A keen naturalist and explorer of foreign lands he was often shipping in and out of England with sometimes thousands of specimens from the great wilds of the world. In 1821 he was returning from an expedition to Guiana with several crates of nature’s wonders. The customs officer on duty that day at Liverpool dock was one Mr. Lushington.

Lushington, clearly not a fan of the wilderness, insisted Waterton pay a costly fee to import his goods. Waterton, baffled as to why he should be taxed on items which were not for commercial gain eventually abated and paid the escalated fee. Some three years later, Waterton was coming back from Guiana once again but this time he carried with him a very unique specimen indeed. A creature called Nondescript which he had hunted and killed. It had a human head, with a thick monkey fur around its chops.

Waterton expounded on the creature in his travelogue, Wanderings in South America. Soon enough, his contemporaries started suggesting the Nondescript was not a real creature at all. In fact, others went so far as to say that the taxidermied head, which Waterton had stuffed himself, rather looked like the backend of a howler monkey. Of course, the whole thing was a hoax and it is believed that Waterton created the creature as a dig to the customs officer Mr. Lushington who, so it is said, the Nondescript somewhat resembles.