Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Top 10 Recent American Industrial Disasters

World attention is right now focused on the Gulf Coast of the United States, where one of the worst industrial disasters of all time is slowing playing itself out. The Deepwater Horizon oil platform explosion and sinking killed 11 workers, but it is the massive environmental disaster caused by the leaking of hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico that is making it probably the worst industrial environmental disaster in US history.

Industrial disasters are a unique post-industrial age creation of man. Industrial disasters have killed untold thousands of people since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Many were avoidable, and needless disasters caused by callous disregard for human safety in an unending quest for money. Others were unforeseen and accidental.

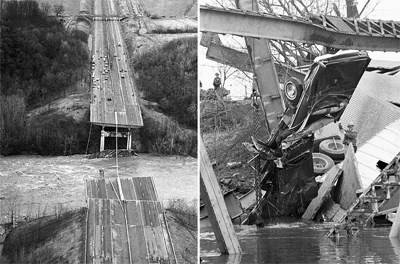

This list focuses on American industrial disasters since the post World War II era. But as we will see, recent industrial disasters such as the 2007 I-35 West Mississippi bridge collapse (13 killed, 145 injured), the 2006 Sago mine disaster (12 killed), 2010 Upper Big Branch mine explosion (29 killed), 2007 Crandall Canyon mine cave in (9 killed), 2008 Kingston Fossil Plant collapse (a huge environmental disaster caused by the largest coal slurry fly ash release in US history), 2008 New York City crane collapse (7 killed) and now the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil platform explosion ( 11 killed) are nothing new. Similar disasters have played themselves out, here in the USA, over the last 65 years and, like the Deepwater Horizon disaster, there appears to be no end in sight to the death and destruction caused by these catastrophes. Let’s take a look back at ten of the worst industrial disasters since 1945.

This Silver Bridge was a suspension bridge built in 1928 and named for the color of its aluminum paint. The bridge connected Point Pleasant, West Virginia and Kanauga, Ohio, over the Ohio River. On December 15, 1967, the Silver Bridge collapsed while it was full of rush-hour traffic, resulting in the deaths of 46 people. Two of the victims were never found. Investigation of the wreckage pointed to the cause of the collapse being the failure of a single eye bar in a suspension chain, due to a small defect 0.1 inch (2.5 mm) deep. Analysis showed that the bridge was carrying much heavier loads than it had originally been designed for and had been poorly maintained. The collapsed bridge was replaced by the Silver Memorial Bridge, which was completed in 1969.

In March 25, 1947, the Centralia No. 5 coal mine exploded near the town of Centralia, Illinois, killing 111 people. The explosion was caused when an under burdened explosive detonation ignited coal dust. At the time of the explosion, 142 men were in the mine; 111 miners were killed by burns and other injuries. Only 31 miners escaped. Following the disaster, John L. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers, called a two-week national memorial work stoppage on 400,000 soft-coal miners. Lewis also blamed the then Secretary of the Interior, Julius Krug, for the men’s deaths because he felt the Department of the Interior was not adequately enforcing new and stricter mine safety rules which had been enacted only a year earlier. Lewis called for Krug’s resignation, but President Harry Truman, who regarded the mourning strike as a sham, rejected this demand.

The disaster did force Congress to address mine safety. In August 1947, Congress passed a joint resolution calling on the Bureau of Mines to inspect coalmines and to report to state regulatory agencies any violations of the federal code. American folksinger Woody Guthrie wrote and recorded a song about the Centralia mine disaster entitled The Dying Miner.

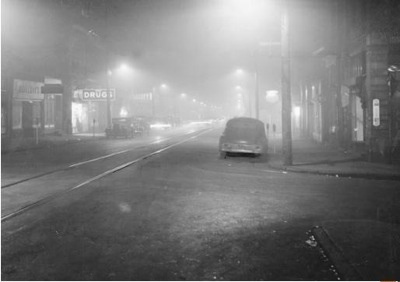

The following year, 1948, a different type of industrial disaster struck the United States, this one invisible, but no less deadly than the explosion in Centralia in1947. The Donora Smog was an historic air inversion pall of smog that killed 20 and sickened 7,000 people in Donora, Pennsylvania, a mill town on the Monongahela River, 24 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

The smog first rolled into Donora on October 27, 1948. By the following day it was causing coughing and other signs of respiratory distress for many residents. Many of the illnesses and deaths were initially attributed to asthma. The smog continued until it rained on October 31, by which time 20 residents of Donora had died and approximately a third to one half of the town’s population of 14,000 residents had been sickened. Even ten years after the incident, mortality rates in Donora were significantly higher than those in other communities nearby.

Sulfur dioxide emissions from U.S. Steel’s Donora Zinc Works and its American Steel & Wire plant were frequent occurrences in Donora. What made the 1948 event more severe was a temperature inversion, in which a mass of warm, stagnant air was trapped in the valley, the pollutants in the air mixing with fog to form a thick, yellowish, acrid smog that hung over Donora for five days. The sulfuric acid, nitrogen dioxide, fluorine and other poisonous gases that usually dispersed into the atmosphere were caught in the inversion and accumulated until the rain ended the weather pattern.

It was not until Sunday morning the 31st of October that a meeting occurred between the operators of the plants, and the town officials. The plants were shut down until the rain came, whereupon the plants resumed normal operation. A study released in December 1948 showed that thousands more Donora residents could have been killed if the smog had lasted any longer than it had.

U.S. Steel never acknowledged responsibility for the incident, calling it “an act of God”. The Donora Smog is often credited for helping to trigger the clean-air movement in the United States, whose crowning achievement was the Clean Air Act of 1970, which required the United States Environmental Protection Agency to develop and enforce regulations to protect the general public from exposure to hazardous airborne contaminants.

The Buffalo Creek Flood was a disaster that occurred on February 26, 1972, when the Pittston Coal Company’s coal slurry impoundment dam #3, located on a hillside in Logan County, West Virginia burst four days after having been declared ‘satisfactory’ by a federal mine inspector.

The resulting flood unleashed approximately 132 million gallons of black wastewater. The flow created a wave of black coal ash muck, which crested at over 30 feet high and ran down upon the residents of 16 coal-mining hamlets in Buffalo Creek Hollow. Out of a population of 5,000 people, 125 were killed, 1,121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless. 507 houses were destroyed, in addition to forty-four mobile homes and 30 businesses. The disaster also destroyed or damaged homes in six surrounding towns. In its legal filings, Pittston Coal referred to the accident as “an Act of God.”

Dam #3, constructed of coarse mining refuse dumped into the Middle Fork of Buffalo Creek starting in 1968, failed first, following heavy rains. The water from Dam #3 then overwhelmed Dams #2 and #1. Dam #3 had been built on top of coal slurry sediment that had collected behind dams # 1 and #2, instead of on solid bedrock. Dam #3 was approximately 260 feet above the town of Saunders when it failed.

The Willow Island disaster was the collapse of a cooling tower under construction at a power station at Willow Island, West Virginia, on Thursday April 27th 1978. Falling concrete caused the scaffolding to collapse. 51 construction workers were killed. It is thought to be the largest construction accident in American history. The disaster occurred when the Allegheny Power System was building a new power plant with two giant natural draft cooling towers. The usual method of scaffold construction for building large cooling towers has the base of the scaffold built on the ground, with the top being built higher to keep up with the height of the tower.

This scaffolding was different. It was bolted to the structure as it was being built. A layer of concrete was poured, then after the concrete forms were removed the scaffolding was raised and bolted onto the new section. On April 27th 1978 tower number 2 had reached a height of 166 feet Just after 10 AM, as the third lift of concrete was being raised, the cable hoisting that bucket of concrete went slack. The crane that was pulling it up fell toward the inside of the tower. The previous day’s concrete, Lift 28, started to collapse. Concrete began to unwrap from the top of the tower, first peeling counter-clockwise, then in both directions. A jumble of concrete, wooden forms and metal scaffolding fell into the hollow center of the tower. Fifty-one construction workers were on the scaffold at the time. All fell to their deaths.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) investigation showed that, like most disasters, it was a series of errors, short cuts and accidents that triggered the event. Scaffold was attached to concrete that hadn’t had time to sufficiently cure. Bolts were missing and the existing bolts were of insufficient grade. There was only one access ladder, restricting ability to escape. An elaborate concrete hoisting system was modified without proper engineering review. And as is almost always seems to be the case, contractors were rushing to speed construction.

The second major construction project industrial disaster to make this list occurred nine years later. The L’Ambiance Plaza was a 16-story residential project under construction in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Its partially erect frame completely collapsed on April 23, 1987, killing 28 construction workers. Failure was possibly due to high stresses placed on the floor slabs by the lift slab technique. There was a school of thought that this accident highlighted the deficiencies of lift slab construction. This accident prompted a major nationwide federal investigation into this construction technique, as well as a temporary moratorium of its use in Connecticut. L’Ambiance Plaza was planned to be a sixteen-story building with thirteen apartment levels topping three parking levels. It consisted of two offset rectangular towers, 63 ft by 112 ft each, connected by an elevator.

At the time of collapse, the building was a little more than halfway completed. In the west tower, the ninth, tenth, and eleventh floor slab package was parked in stage IV directly under the twelfth floor and roof package. The shear walls were about five levels below the lifted slabs. The workmen were tack welding wedges under the ninth, tenth, and eleventh floor package to temporarily hold them into position when they heard a loud metallic sound followed by rumbling. An ironworker who was installing wedges at the time, looked up to see the slab over him “cracking like ice breaking.” Suddenly, the slab fell on to the slab below it, which was unable to support this added weight and in turn fell.

The entire structure collapsed, first the west tower and then the east tower, in 5 seconds, only 2.5 seconds longer than it would have taken an object to free fall from that height. Two days of frantic rescue operations revealed that 28 construction workers died in the collapse, making it the worst lift-slab construction accident.

The explosion at the Imperial Sugar refinery was an industrial disaster that occurred on February 7, 2008 in Port Wentworth, Georgia. Thirteen people were killed and 42 injured when a dust explosion occurred at a sugar refinery owned by Imperial Sugar. Dust explosions had been an issue of concern amongst United States authorities since three fatal accidents in 2003, with efforts made to improve safety and reduce the risk of recurrence. However, a safety board had criticized this as inadequate.

The sugar refinery was a four-story structure on the bank of the Savannah River and was the second largest in the US. Workers described the factory as antiquated, with much of the machinery dating back more than 28 years, but say the site was kept in operation because it had good access to rail and shipping links for transport. At one time the facility refined 9% of the nation’s sugar requirements. The explosion occurred at 7:00 p.m. local time in what was initially believed to be a room where sugar was bagged by workers. There were 112 employees on-site at the time. Most of the victims were seriously burned, with ages ranging from 18 to 50.

By February 14, 2008, the worst of the fire had been extinguished but the 100-foot sugar storage silos remained alight despite attempts to put the fire out. The smoldering, molten sugar in the silos was unlike anything most fire fighters had ever experienced. It is believed that the factory’s outdated construction materials and methods contributed to the severity of the blaze. The ceiling was of wooden tongue and groove design, and creosote used throughout was known as “fat lighter” because of the fire risk it posed. As a result of the disaster new safety legislation has been proposed, while the local economy has slumped because the factory remains offline, although Imperial intends to rebuild.

On March 23, 2005, a fire and explosion occurred at BP’s Texas City Refinery in Texas City, Texas, killing 15 workers and injuring more than 170 others. BP was charged with violating federal environment crime laws and has been subject to lawsuits from the victim’s families. Later, an $87 million fine was imposed by the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which claimed that BP had failed to implement safety improvements following the disaster.

The Texas City Refinery is the second-largest oil refinery in the state and the third largest in the United States. The explosion occurred in a unit where light and heavy gasoline components were being separated, and octane was being added. Due to operator error, gasoline was forced in to a pressure release system called a blow down drum. The pressure was too much and overwhelmed it, resulting in liquids spilling out and accumulating on the ground, which created a highly flammable and combustible vapor cloud. The hydrocarbon vapor cloud was then ignited by a nearby contractor’s pickup truck. The report identified numerous failings in equipment, risk management, staff management, working culture at the site, maintenance and inspection and general health and safety assessments.

An independent panel to investigate the safety culture and management systems at BP North America was set up and led by former US Secretary of State, James Baker III. The Baker panel report was released on January 16, 2007. The principal finding was that BP management had not distinguished between “occupational safety” (i.e. slips-trips-and-falls, driving safety, etc.) vs. “process safety” (i.e. design for safety, hazard analysis, material verification, equipment maintenance, process upset reporting, etc.). BP confused improving trends in occupational safety statistics for a general improvement in all types of safety. BP also decided against replacing the antiquated blow down system with a more modern (and expensive) system that would not have allowed the excess gasoline to flow out and onto the ground and would have prevented the explosion.

The BP refinery explosion was hardly the worst industrial disaster to strike this town or state. The year 1947 was a very bad year for industrial disasters. Only three weeks after the Centralia Mining Disaster, on April 16, 1947, a fire started on board the French-registered vessel SS Grandcamp in the Port of Texas City, Texas. The fire detonated approximately 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate and the resulting chain reaction of fires and explosions killed at least 581 people.

The SS High Flyer was another ship in the harbor at the time, about 600 feet away from the SS Grandcamp. The High Flyer contained an additional 961 tons of ammonium nitrate and 1,800 tons of sulfur. The ammonium nitrate in the two ships and in the adjacent warehouse was fertilizer on its way to farmers in Europe. Around 08:10, smoke was spotted in the cargo hold of the Grandcamp. Attempts to control the fire failed.

Shortly before 9:00 AM, the Captain ordered his men to steam the hold, a firefighting method where steam is piped in to put out fires in the hope of preserving the cargo. Meanwhile, the fire had attracted a crowd of spectators along the shoreline, who believed they were a safe distance away. Spectators noted that the water around the ship was already boiling from the heat, an indication of runaway chemical reactions. The cargo hold and deck began to bulge as the forces increased inside.

At 09:12, the ammonium nitrate inside the vessel detonated. The tremendous blast sent a 15-foot wave that was detectable over nearly 100 miles of the Texas shoreline. The Grandcamp explosion destroyed the Monsanto Chemical Company plant and resulted in ignition of refineries and chemical tanks on the waterfront. The force of the explosion was so great that sightseeing airplanes flying nearby had their wings shorn off. People felt the shock 250 miles away in Louisiana. The entire volunteer fire department of Texas City was killed in the initial explosion.

But the disaster was not over. The first explosion ignited ammonium nitrate cargo in the High Flyer. The crews attempted to save the ship and failing that, tried to move it out of the harbor but about fifteen hours after the explosions aboard the Grandcamp, the High Flyer blew up killing at least two more people and increasing the damage to the port and other ships.

The Texas City Disaster is generally considered the worst industrial accident in American history. Witnesses compared the scene to the devastation at Nagasaki. The official death toll was 581. Of the dead 63 were never identified. A remaining 113 people were classified as missing, for no identifiable parts were ever found. There is some speculation that there may have been hundreds more killed but uncounted, including visiting seamen, non-census laborers and their families, and an untold number of travelers.

Over 5,000 people were injured, with 1,784 admitted to twenty-one area hospitals. More than 500 homes were destroyed and hundreds damaged, leaving 2,000 homeless. The seaport was destroyed – the property damage was estimated at $100 million. A 2-ton anchor of Grandcamp was hurled 1.62 miles and found in a 10-foot crater. It now rests in a memorial park

Vermiculite, an ore found in the area of Libby Montana in 1881, had been mined since 1919 and sold under the brand name Zonolite. Vermiculite is a mineral that was used mostly as an insulator in homes and is also an additive in potting soil (the bright sparkly stuff you see mixed in with the brown and black soil). The problem was, the vermiculite was contaminated with asbestos and this had been widely known by the company for many years, even prior to W. R. Grace and Company’s purchase of the Zonolite mine in 1963.

In 1999, the Seattle Post-Intellingencer published a series of articles documenting extensive deaths and illness from the asbestos contaminated vermiculite at the mine. These deaths and illnesses from asbestos exposure were not simply workers but also people living in the town of Libby, people who had never worked a day at the plant. This was very unusual as most victims of asbestos exposure actually work with the material in plants, mines, or ships, and perhaps bring the asbestos dust home to their family members on their clothing. But in Libby, people were becoming ill and dying of asbestosis and mesothelioma (diseases caused only by asbestos exposure) who never stepped foot inside the mine or plant, and had no relative who ever worked there. Finding cases of asbestosis (which requires repeated, long term exposures to asbestos over many years) in people with no known industrial exposure was unheard of, until the asbestos-contaminated vermiculite disaster in Libby Montana came to light.

As it turns out, the mine owners knew that the vermiculite ore that came out of the Libby mine was contaminated with a form of asbestos called tremolite – an especially deadly form of asbestos. They also knew there was no way they could remove the asbestos contamination from the vermiculite ore they were mining and processing in Libby, and shipping out by rail car to scores of other processing plants and manufacturers who used the vermiculite as a raw material in their products. Even knowing the deadly effects of the asbestos in their vermiculite, WR Grace continued to exposure their workers, the people in the town of Libby, and the employees of other manufacturers who used the vermiculite.

It is unknown how many have died of asbestos-related disease. One study comparing the Montana and US mortality rates against those in Libby from 1979-1998 found there was a 20-40% increase in malignant and non-malignant respiratory death for the Libby inhabitants. No one can say how many were killed by asbestos exposure from the vermiculite shipped out of Libby to other parts of the country.

The EPA estimates more than 274 area deaths were caused by asbestos-related diseases. A full 17% of Libby residents who were tested were found to have pleural abnormalities, which may be related to exposure to asbestos. In February 2005 the Federal Government began a criminal conspiracy prosecution of WR Grace and of seven current and former Grace employees. The government alleged that Grace conspired to hide from employees and the town residents the asbestos dangers and that it knowingly released asbestos into the environment. On May 8, 2009, a jury found W.R. Grace & Co. and the accused employees not guilty on all counts, ending what was called the biggest environmental-crime prosecution in U.S. history.

Though not a single event like the others, this was a mammoth industrial scale disaster played out one nuclear detonation at a time, over a twelve-year period. The full human impact of the approximately 200 above ground nuclear weapons tests conducted in the western USA, at the Nevada Proving Grounds, may never be known. What is known is that the detonation of nuclear weapons, in the atmosphere, accounted for a total yield of 153.8 megatons of TNT explosive and large amounts of radioactive fall out over a huge portion of the United States (and the world).

Between 16 July 1945 and 23 September 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous nuclear testing. Until November 1962, the vast majority of the U.S. tests were atmospheric (that is, above-ground). After the acceptance of the Partial Test Ban Treaty all testing was regulated underground, in order to prevent the dispersion of nuclear fallout. The U.S. program of atmospheric nuclear testing exposed a huge portion of the US population to the hazards of fallout. Estimating exact numbers, and the exact consequences, of people exposed has been medically very difficult.

A 1979 study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that – “A significant excess of leukemia deaths occurred in children up to 14 years of age living in Utah between 1959 and 1967. This excess was concentrated in the cohort of children born between 1951 and 1958, and was most pronounced in those residing in counties receiving high fallout.”

In a report by the National Cancer Institute, released in 1997, it was determined that ninety atmospheric tests at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) deposited high levels of radioactive iodine-131 across a large portion of the contiguous United States, especially in the years 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1957—doses large enough, they determined, to produce 10,000 to 75,000 cases of thyroid cancer.

Radioactive fallout from Cold War nuclear weapons tests across the globe probably caused at least 15,000 cancer deaths in U.S. residents born after 1951, according to data from an unreleased federal study. Certainly a large percentage of the radioactive fall out that Americans were exposed to came from US above ground nuclear weapons testing.

The study, coupled with findings from previous government investigations, suggests that 20,000 non-fatal cancers — and possibly many more — also can be tied to fallout from aboveground weapons tests. The study shows that fallout from scores of U.S. trials at the Nevada Test Site spread substantial amounts of radioactivity across broad swaths of the country. When fallout from all tests, domestic and foreign, is taken together, no U.S. resident born after 1951 escaped exposure.