Misconceptions

Misconceptions  Misconceptions

Misconceptions  Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Top 10 Famous People Named Adolf

With such an odious notoriety in the world’s history as Adolf Hitler, it is not surprising that the male name Adolf will always be associated primarily with the Third Reich Führer. That is also the reason for the decreasing popularity of this, once wide-spread, name after WWII. Nevertheless, there were a lot of well-known personalities named Adolf. This list features 10 famous Adolfs, besides the most notoriously known Adolf Hitler. Most of you will probably be quite surprised by the first entry.

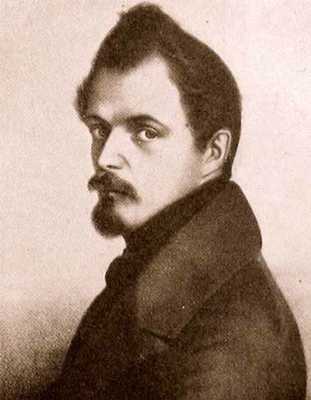

Adolf von Henselt was a German composer and pianist, born at Schwabach, Bavaria. He began to learn the violin at the age of three and the piano at five. As he got a financial help from King Ludwig I of Bavaria, he went to study under Johann Nepomuk Hummel in Weimar for some months, and then moved to Vienna in 1832, where, along with studying composition, he made a great success as a concert pianist. Several years later he moved to Saint Petersburg, and became court pianist and inspector of musical studies in the Imperial Institute of Female Education, and was ennobled in 1876. For summer holidays he usually went to his former homeland, Germany. In 1852 and again in 1867, he visited England, though in the latter year he made no public appearance. He actually had to withdraw from concert appearances by age thirty-three because of a stage fright so bad it was close to paranoia.

Henselt’s playing can be characterized as a combination of Franz Liszt’s sonority with Hummel’s smoothness. It was remarkable for the great use of extended chords and for the perfect technique. Henselt had an immense influence on the next generation of Russian pianists. The entire Russian school of music comes from Henselt’s playing and teaching. A famous Russian composer, Sergei Rachmaninoff, had a very high opinion of Henselt, and considered him one of his most important influences.

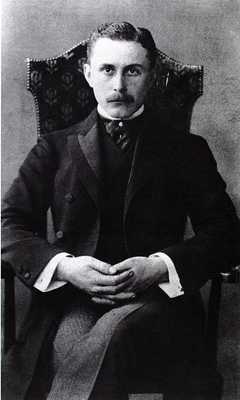

German architect Adolf Loos was born in Brunn, Czechoslovakia, in 1870. He started studying architecture at the Royal and Imperial State Technical College in Rechenberg, Bohemia, but soon was drafted to the army, where he served for two years. He then attended the College of Technology in Dresden for three years. From 1893 to 1896, he lived in the U.S. and worked as a mason, a floor-layer and a dish-washer. He finally got a job with the architect Carl Mayreder and, in 1897, he already had his own practice. He taught for several years throughout Europe, but returned to practice in Vienna, in 1928.

Adolf Loos had great influence in European Modern architecture. Still, he was more known for his writings rather than for his buildings. In his essay Ornament and Crime, he repudiated the florid style of the Vienna Secession, the Austrian version of Art Nouveau. This, and many other essays, are devoted to the elaboration of a body of theory and criticism of Modernism in architecture. Loos established building method supported by reason, as he was convinced that everything that could not be justified on rational grounds was superfluous, and should not exist. Loos preferred pure forms due to economy and effectiveness. He was also against decoration, considering it mass-produced and mass-consumed trash, and believing that culture resulted from the renunciation of passions, thus the absence of ornamentation generated spiritual power. His fight for freedom from the decorative styles of the nineteenth century inspired future architects.

The buildings by Adolf Loos are mostly situated in Vienna, but can also be found in Paris, Prague and other cities.

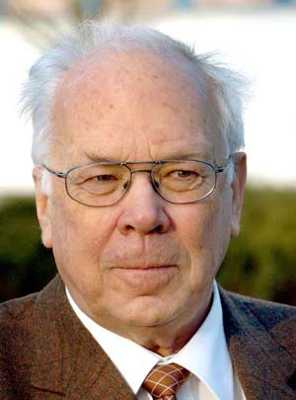

Adolf Merckle, a German billionaire, became one of the victims of financial crisis. In 2009, he committed suicide by throwing himself in front of a train.

Merckle owned the largest pharmaceutical wholesaler in Germany, Phoenix Pharmahandel. He inherited his business from a grandfather but contributed greatly to its development. In 2006, Merckle was the world’s 44th richest man. He faced problems in 2008, during the financial crisis when he made a speculative investment based on his belief that Volkswagen shares would fall. However, in October 2008, Porsche SE’s support of Volkswagen sent shares on the Xetra dax from €210.85 to over €1000 in less than two days, resulting in losses estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars for Merckle.

“The desperate situation of his companies caused by the financial crisis, the uncertainties of the last few weeks and his powerlessness to act, have broken the passionate family entrepreneur and he took his own life,” a family statement said.

The seventh place is shared by the German physiologist Adolf Fick and his ophthalmologist nephew of the same name.

The first started to study mathematics and physics, but then realized he was more interested in medicine. In 1851, he earned his doctorate in medicine at Marburg. After that he worked as a prosector in anatomy. In 1855, Fick’s law of diffusion was introduced. The law, which applies equally to physiology and physics, governs the diffusion of a gas across a fluid membrane. Fifteen years later, Adolf Fick introduced a technique for measuring cardiac output, called the Fick principle. Fick is also known as an inventor of the tonometer. This work influenced his nephew, who invented the contact lens.

Adolf Gaston Eugen Fick was actually raised in the family of his uncle after the premature death of his father, anatomy professor Ludwig Fick. He studied medicine in Würzburg, Zürich, Marburg und Freiburg. In 1887, he tested an afocal scleral contact shell, made from heavy brown glass, on rabbits then on himself and, finally, on a small group of volunteers. It was considered the first successful model of a contact lens. During WWI, Fick headed the field hospitals in France, Russia and Turkey. At the same time he continued working on ophthalmologic anatomy and optics.

A Jewish-born German mathematician, Adolf Hurwitz was described by Jean-Pierre Serre as “one of the most important figures in mathematics in the second half of the nineteenth century”. He was taught mathematics by Hermann Schubert, who found out his talent for mathematics and persuaded Hurwitz’s father to allow Adolf to go to university. He also arranged for Hurwitz to study with Felix Klein at Munich. Under Klein’s direction, Hurwitz became a doctoral student. His dissertation, in 1881, concerned elliptic modular functions. After working for two years at the University of Göttingen, and being an Extraordinary Professor at the Albertus Universität in Königsberg, Hurwitz took a chair at the Eidgenössische Polytechnikum Zürich, in 1892, and remained there for the rest of his life. Among his students there was Albert Einstein.

Hurwitz was one of the early masters of the Riemann surface theory and one of the authors of Riemann–Hurwitz formula. Hurwitz was particularly interested in number theory. He studied the maximal order theory for the quaternions. In number theory, there’s a Hurwitz theorem named for him.

Adolf Bastian was a major ethnologist of the 19th century, who contributed greatly to the development of such disciplines as ethnography and anthropology. His theory of the Elementargedanke became a basis for Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes.

Bastian’s career at university was very broad. He first studied law at the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, and biology at what is today the Humboldt University of Berlin, the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena and the University of Würzburg. There he attended lectures by Rudolf Virchow and became interested in what we now know as ‘ethnology’. He eventually earned a degree in medicine, in Prague in 1850. Bastian worked as a ship’s doctor and for 8 years he traveled around the world. It was his first travel spent outside the German Confederation. Having returned home in 1859, he wrote a popular account of his travels and an ambitious three volume work, Man in History, which became one of his most well-known works.

In 1861, he went on a four-year trip to Southeast Asia, which led to the six volume work entitled The People of East Asia. For the next eight years, Bastian stayed in the North German Confederation, where he was involved in the creation of several key ethnological institutions, in Berlin. He made copious contributions to Berlin’s Royal museum and the second museum, the Museum of Folkart, was founded largely thanks to Bastians contributions. Its collection of ethnographic artifacts became one of the largest in the world for that time, and for decades to come. He also worked with Rudolf Virchow to organize the Ethnological Society of Berlin. During this period, he was the head of the Royal Geographical Society of Germany. Since the 1870s, Bastian was traveling extensively in Africa as well as the New World. He died during one of his journeys, in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

In the 1850’s and 1860’s, the German chess master Adolf Anderssen was considered to be the strongest chess player. He took the first prize in over half of the European tournaments, from 1851 to early 1878. In 1851, he represented Germany in the first international chess tournament, which took place in London. The tournament made Anderssen the world’s leading chess player. A month later the London Chess Club organized a tournament which included several players who had competed in the International Tournament. Anderssen won again. During his career Anderssen also knew defeat. He didn’t do as well in matches as in tournaments. In 1866, Anderssen lost a close match with Wilhelm Steinitz. At the Leipzig tournament in 1877, Anderssen came second, behind Louis Paulsen. The tournament was organized on the initiative from the Central German Chess Federation, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Anderssen’s learning the chess moves. Remarkably, it was the only tournament ever organized to commemorate a competitor.

All in all, Anderssen was a very important figure in the development of chess problems. He is known for his brilliant sacrificial attacking play, particularly in the “Immortal Game” (1851) and the “Evergreen Game” (1852). Adolf Anderssen was honored to be an “elder statesman” of the game, to whom others turned for advice or arbitration.

During his life, the German writer and Freemason Adolph Freiherr Knigge (Freiherr is not a personal name but a title, meaning Baron) was a member of Corps Hannovera, the Court Squire and Assessor of the War and Domains Exchequer in Kassel, Chamberlain at the Weimar court and a member of Bavarian Illuminati.

Still he’s mostly remembered for one book he wrote. This book should be known by any German. Knigge’s Über den Umgang mit Menschen (On Human Relations) is a fundamental sociological and philosophical work on principles of human relations and also a guide to behavior, politeness and etiquette. There even appeared the word Knigge in German language to mean “good manners” or books on etiquette.

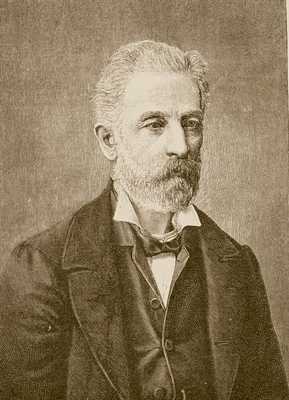

Adolph von Menzel is one of the most renowned German artists. He was considered the most successful artist in Germany in the 19th century. In 1833, Menzel studied for a short period of time at the Berlin Academy of Art. He drew from casts and ancient sculptures. But generally, Menzel was self-taught.

Menzel was the first to largely introduce to Germany the technique of wood engraving. From 1839 to 1842, he produced 400 drawings, illustrating the Geschichte Friedrichs des Grossen (History of Frederick the Great) by Franz Kugler. After that, he brought out Friedrichs der Grossen Armee in ihrer Uniformirung (The Uniforms of the Army under Frederick the Great), Soldaten Friedrichs der Grossen (The Soldiers of Frederick the Great); and finally, following the order of the king Frederick William IV, he illustrated the works of Frederick the Great, Illustrationen zu den Werken Friedrichs des Grossen (1843-1849). These works established Menzel’s claim to be considered one of the first illustrators of his day.

His popularity in Germany, especially due to his politically propagandistic works, was so great that most of his major paintings remained in Germany, as a lot of them were quickly acquired by Berlin museums. Menzel himself traveled a lot searching for subjects for his art, visiting exhibitions and meeting with other artists, but still spent most of his life in Berlin. Although he had many friends and acquaintances, he was, by his own words, detached from others. He probably felt socially estranged for physical reasons, alone—Menzel was about four foot six inches and had a large head.

Adolf Dassler, more known as Adi Dassler, was always a passionate sportsman. Born into the family of a German shoe worker, Adi became a cobbler himself, but he had a dream to create a shoe specifically for athletes. Shortly after WWI, he started to work on it in his mother’s laundry room, assisted by his brothers (the older one, Rudolf, will be later known as the founder of Puma). The brothers soon started a successful business, which was called Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik (Dassler Brothers Shoe Factory). Dassler didn’t miss any sporting event in his quest to make athletes wear the shoes from the Dassler Shoe Factory. At the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, some athletes were wearing these shoes and, during the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, the US athlete Jesse Owens won 4 gold medals wearing Dassler’s shoes. All that was a good advertisement for the company and helped it to establish international contacts.

As WWII began, Adi’s brother Rudolf was drafted. Adi himself produced boots for Wehrmacht (undoubtedly helped by the fact that he voluntarily joined the Nazi Party). After the war, the brothers tried to continue working together, but due to the disagreements Rudolf left Adi and founded his own company, Puma. Adolf Dassler reformed his shoe company and gave it a new name using the short form of his first name and the first three letters of his last name. Adidas is one of the most well-known sportswear companies.