Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

10 Shocking Scandals That Rocked 19th Century Society

The rise of cheap, sensational newspapers in the nineteenth century meant that shocking scandals weren’t just whispered about behind fluttering fans and raised teacups. Ordinary members of the public could sit down at the breakfast table and over tea and toast, read every juicy, salacious, delicious detail of who did what and to whom.

Sadly, Honey Boo Boo wouldn’t be born for another century-plus, so reading newspapers, penny press publications, and scandal sheets was a way for the public to sate its appetite for the disturbing, the sinful, the extraordinary, and the downright ugly. Criminal conversation, beastly behavior, sexual shenanigans … it’s all here in these ten shocking scandals that rocked nineteenth century society to its well-bred core.

Edward Jones, seventeen years old, son of a tailor and by all accounts as unattractive as homemade sin, was discovered in Buckingham Palace in the dressing room next to Queen Victoria’s bedroom. The queen had recently given birth to her first child. As it turned out, this wasn’t the first time Jones had made himself at home in the palace. He’d been sneaking in since 1838. Worse, he’d once been caught with the queen’s underwear stuffed down his pants! His arrest had the newspapers dubbing him, the “Boy Jones.” Despite increased security, he would cause more furor over an apparent inability to stay away from the palace—he was caught again in 1841 and sentenced to hard labor. Eventually, he went to Australia.

![Nuns[1]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/nuns1.jpg)

The case of Saurin v. Starr and Kennedy stirred up English anti-Catholic sentiments as well as selling a great many newspapers and scurrilous pamphlets. Susan Saurin (formerly Sister Mary Scolastica) sued her mother superior, Mrs. Starr, for libel and conspiracy, claiming she’d been unfairly expelled from the convent. The trial played to a packed courtroom. Witnesses gave accounts of Saurin’s supposed crimes, which included eating strawberries and cream (the wicked woman!) and being “excited” in the presence of a visiting priest. To the Protestant jury’s great disappointment, the mother superior later testified she hadn’t meant that kind of excitement. Verdict for the plaintiff; ₤500 damages awarded.

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 against the Austrian Empire, a man stood out for his violent tactics in suppressing the revolutionaries: Julius Jacob von Haynau, an Austrian general who earned the nickname, “the Hyena.” News of his brutality, particularly against Hungarian women, excited much anger in the English public. So much so that when Haynau visited a brewery during a trip to London in 1850, the draymen—drivers of the wagons used to deliver the barrels of beer—attacked him with whips, brooms, and stones. His magnificent moustaches were torn, his clothes ripped off, and the dread “Hangman of Arad,” abandoning his dignity, fled to a nearby inn for sanctuary. The newspapers had a field day.

When Lady Harriet Mordaunt’s daughter was born, doctors thought she might be blind. Lady Mordaunt feared syphilis and confessed to her husband, Sir Charles, that she’d been often unfaithful to him. Among her lovers was the Prince of Wales (Queen Victoria’s eldest son, heir to the throne, and later King Edward VII). This bombshell resulted in the infamous Mordaunt divorce trial. Technically, the trial was meant to settle whether Lady Mordaunt was sane enough for a divorce to proceed. To the queen’s fury, the married Prince of Wales was called upon to testify about his relationship with Lady Mordaunt in open court. He denied the adultery. The jury decided the lady suffered from “puerperal mania”—post partum depression. She was committed to an asylum. The divorce was eventually granted.

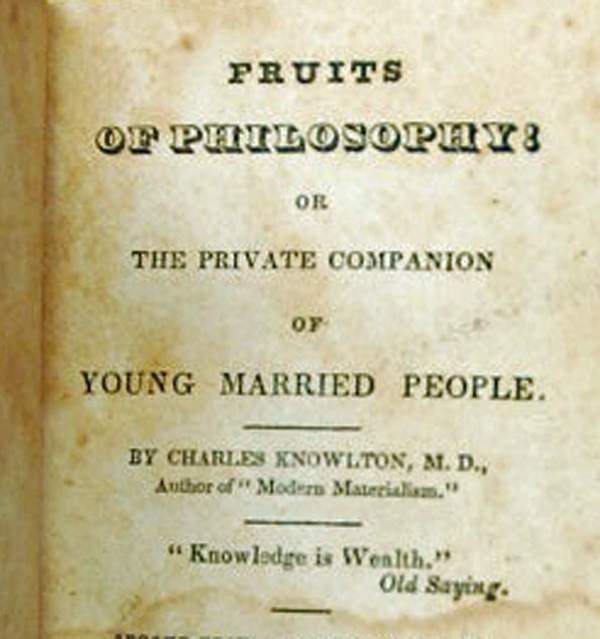

Annie Besant, a noted feminist, Theosophist, and women’s rights activist, and Charles Bradlaugh, an infamous atheist, published The Fruits of Philosophy: the Private Companion for Young Married Couples, a pamphlet by an American doctor, Charles Knowlton, and previously judged obscene. Why? The subject was contraception. Public discussion of sex was regarded as disgraceful. Twenty minutes after the first copies went on sale, the pair were arrested following a complaint by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. Their trial was a sensation. The jury decided Besant and Bradlaugh hadn’t meant to deprave the public and they were ordered not to republish the pamphlet. They republished it anyway.

In London, at the Druid’s Hall (the meeting place for the Ancient Order of Druids and occasionally hired out to non-Druids) during a masked ball, George Campbell, thirty five years old, and John Challis, sixty years old, were apprehended by the police for “exciting others to commit an unnatural offense.” Both men were dressed in women’s clothes. Homosexuality being illegal, a trial proceeded which scandalized the city. Campbell claimed he’d only gone to the party in a dress so he could witness the “vice” for himself and later preach against it. Both men’s character witnesses painted impeccable pictures. They were let off with stern warnings.

While traveling to London by train, Colonel Valentine Baker, a respected military figure and friend of the Prince of Wales, was accused of raping Rebecca Dickenson, twenty-two years old. At the trial, Dickenson alleged that the colonel had tried to raise her skirts, put his hand in her underwear, and kiss her many times on the lips. To save her virtue, though the train was in motion, she escaped to the step outside the first class railway carriage and clung there, screaming for help. Baker’s trial caused discussion over the British class system since it was argued, quite rightly, that if he’d been in third class, he’d have gotten away with it. Although he escaped the rape charge, he was convicted of committing an indecent assault.

When a policeman stopped to question a fifteen year old telegraph boy about why he had eighteen shillings in his pocket in today’s money, that’s about ₤77 or $122 USD), he kicked off a scandal that reached all the way to the British royal family. The boy hadn’t stolen the money—he’d earned it sleeping with gentlemen at a house on Cleveland Street, and so did other young telegraph boys. Scotland Yard raided the house. Among the well connected visitors was Lord Arthur Somerset, the Duke of Beaufort’s son. Prince Victor Albert, nicknamed “Prince Eddy” was also an alleged customer. While the British press kept his name out of the papers, American and French reporters weren’t so circumspect. Several of the men involved in the pedophilia ring – including Somerset – fled the country to avoid prosecution.

In 1846, after wedding John Ruskin, the leading critic of the age, the beautiful, young, and bright Euphemia “Effie” Gray expected her life to go the usual wife and motherhood route. Instead, the older Ruskin put off consummating the marriage. And put it off, and put it off until years later, she met and fell in love with another man, John Everett Millais, a Pre-Raphaelite painter and Ruskin’s protégé. She abandoned her unhappy marriage to Ruskin in 1854 and filed for annulment on the grounds that she was still a virgin. The revelations caused unflattering comment on her character in the papers. She married Millais, though she paid a price—never again would she be allowed to attend a social event if Queen Victoria was present. She probably didn’t mind that much, since she and Millais had eight children together.

When William Charles Yelverton met, wooed, and ultimately became twenty year old Theresa Longworth’s lover, he “ruined” her in the eyes of Victorian society because they weren’t married. She accepted his excuses, took to public speaking to support their life together, even going so far as to follow him to Scotland and Ireland so their affair could continue, but eventually, she expected a wedding. She got the matrimonial ring in a secret church ceremony in 1857. She also got a shock a year later when Yelverton made a bigamous marriage to another woman. Theresa eventually took him to court seeking alimony. He insisted their marriage was invalid because of their religious differences—he was Catholic and she was Protestant. After many appeals, the case went in his favor.