Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

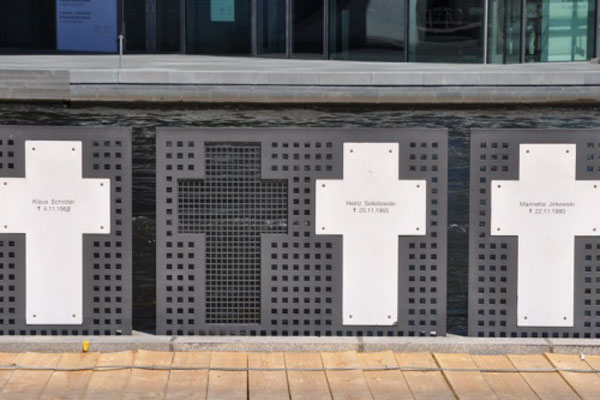

10 Depressing Stories From the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall—or the “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart” as it was fondly called by the people who came up with the idea—was nearly one hundred miles long. That’s one hundred miles of concrete slab, peppered with guard towers, traps and more barbed wire than you could shake a stick at.

During the thirty-odd years it was at its most impenetrable, hundreds of attempts were made to cross it, and many people from all walks of life died trying. Here are ten of the most depressing stories relating to those failed crossings of the Berlin Wall:

Peter Fechter was an eighteen-year-old who wanted nothing more than to taste the sweet air of West Germany. His plan was simple: he and a friend would wait until an opportune moment, then sprint across the “death strip” (it was actually called that) and vault the wall to freedom.

Although his friend made it, Peter was shot in the pelvis by a guard and fell inches short of his goal. The whole drama took place in front of hundreds of witnesses, soldiers and journalists on the western side of the wall. Peter lay in agony for more than an hour, while sympathetic bystanders literally a few feet away could do nothing but watch as he died. When he finally passed away, an East German soldier picked up his body and carried it back to East Berlin, followed by thousands of futile boos.

Tunneling out of East Germany was a fairly common activity during the time of the Berlin Wall. Tunneling into East Germany, on the other hand, was almost unheard of. But that was exactly what two men did one day, in a desperate attempt to help their wives and children escape the East.

When the two men arrived in East Germany, armed guards were waiting; it turned out that one of the wives’ family members had betrayed them. One of the men was shot to death by the guards who greeted them on the other side of the tunnel, and the other spent ten years in prison. Bringing a whole new meaning to rubbing salt in the wound, his wife divorced him while he was in there.

When six-year-old Andreas Senk was accidentally pushed into the water by a friend during play, it seemed at first that he was rather lucky. The stretch of water he fell into was heavily guarded by dozens of soldiers in patrol boats and watchtowers.

But no attempt was made by any East German official to rescue the child. Though it’s arguable that the guards simply failed to notice the boy, they also refused to assist a West German rescue effort—even going so far as to train their guns on the firemen conducting the search. Four more children died in a similar way before an agreement was reached that put safety precautions in place.

It’s easy to forget that the guards stationed at the Berlin Wall were genuine soldiers, and that they therefore enjoyed all the perks normally offered to soldiers, such as glittering medals. One of the more infamous of these was the Medal For Exemplary Border Service.

Its infamy stemmed from the fact that it was generally given to guards who had successfully shot unarmed civilians. For example, the soldier who shot forty-year-old Ernst Munst was given the medal due to the fact he “handled his weapon superbly and put it to use masterfully”—in other words, he shot the unarmed Munst in the head.

Interestingly, almost no guards were arrested as a result of any death on the wall. One of the harsher sentences was passed to a guard who shot Walter Kittel: he received a two-year suspended sentence for manslaughter after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Bunny rabbits thrived in the so-called Death Strip, between the two walls. With virtually no human interference, the rabbits were free to frolic and breed.

So although the collapse of the wall was a great event for the people of Germany, it turned out to be a death sentence for the Berlin bunnies. Many were trampled to death by elated Germans desperately trying to reach loved ones. The rabbits that did survive managed to hide in nearby bushes, where many of them starved to death.

Bernd Lünser was a twenty-two-year-old student from one of Berlin’s universities. When the wall went up, he was left stranded and unable to reach his place of study. Eager to continue on his academic path, Bernd planned to scale a rooftop and then use a clothes line to descend into West Germany.

But his plan was foiled by a group of guards. Bernd, struggling with the men, called for West Germans to aid him in some way; his compatriots quickly responded by creating a makeshift net for Bernd to leap into. Tragically, the struggle caused Bernd to miss his jump by a few feet, and he was killed instantly.

The Berlin Wall split many families in two, which is part of the reason why escape attempts were so common: people simply wanted to go home.

Strict border regulations meant that if your family member died trying to escape across the wall, you weren’t even allowed to attend their funeral. The dead would often be buried anonymously—as was the case with Klaus Brueske, whose mother and seven siblings were prevented from visiting him, even in death.

Though painted as inhuman monsters by the other side, the border guards were essentially regular people doing their (admittedly rather evil) job. They were for the most part members of the community, and part of the fabric of everyday life.

When a group of children asked some border guards to show them the weapons they carried, the guards eventually relented and explained the functions of the guns. But in a freak accident, one of the weapons discharged and struck a nearby thirteen-year-old schoolboy, Wolfgang Glöde. The fate of Private K (the guard responsible) isn’t known.

Almost every person who died anywhere near the Berlin Wall has had their lives very thoroughly researched and put on display, so that people today might appreciate what they went through. To date, only one person has never been identified.

All we know about this man is that he drowned in the full view of onlookers, and that no one ever came to claim his body from either East or West Germany. Despite decades of scholarly work and research, nothing else has ever been discovered about this man. If dying is one of the worst things that can happen to a person, then dying completely anonymously—with no one around to care—must take bad luck to a whole new level.

It’s unknown exactly what prompted Ingrid and Klause H. to escape East Berlin, but the reason was presumably a very good one.

While hiding in the back of a truck, Ingrid’s young child Holger began to stir. Terrified that a guard would hear, Ingrid muffled the baby’s cries with her hand. But Ingrid was completely unaware that little Holger was suffering from bronchitis, and was therefore unable to breathe through his nose.

When the truck arrived in West Germany, Ingrid and Klause had gained their freedom, but had lost their son.

Karl Smallwood has written a book, Internet Adventures, which you can read about here. And you can follow him on Twitter.