Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

10 Weird Military Plans to Use Animals as Weapons

Animals have been used in war for a long time: ever since we learned that sitting on a horse was faster than running. These ten examples show some of the more unusual ways we’ve used animals as weapons of war over the years.

And just as a note, this doesn’t include blatantly heinous tactics like strapping bombs to dogs—those people should never be honored. All of these entries are unique either for being ridiculously awesome, creative, or just, well, sort of bizarre.

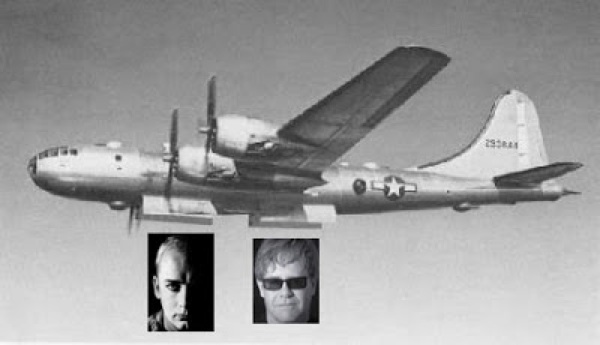

In 1957, at the height of the Cold War, Great Britain hatched a plan to bury a series of nuclear warheads throughout Germany as a failsafe in case the Soviet army attempted to invade Europe from the east. Immediately they encountered a problem: the winter temperatures of the North German plain—where they planned to bury the nukes—got way too cold for the bombs’ electronics to function.

So Britain’s best military scientists went to work, and came up with the most ridiculous idea ever: chickens, they said, would produce enough body heat to keep the electronic circuits warm. With a week’s supply of food, the chickens would stay alive long enough to keep the bombs in working order. Eventually the project was cancelled, not because it was crazy, but because Britain was worried about the political aspects of detonating nuclear warheads in allied territory, which makes a lot more sense.

Before long-distance communication was widely available, homing pigeons were often used to send messages. In World War II alone, the UK used an estimated 250,000 homing pigeons to discretely get messages out from troops behind enemy lines, especially in situations where they couldn’t use radios. It’s the perfect tactic: A trained pigeon can travel more than 1,100 miles (1,800 km) to a precise location, and they don’t send out any signals that can be traced by the enemy. But since pigeon technology isn’t exclusive to any one army, the Germans were sending messages via pigeon as well.

So the British upped the ante by training a small force of peregrine falcons to patrol the coast of Great Britain and intercept outgoing homing pigeons. The project appears to have been successful, and at least two enemy pigeons were captured alive, then jokingly referred to as prisoners of war—although this was a time when pigeons were decorated for acts of valor, so maybe it wasn’t a joke.

Since the 1960s, the US Navy has had an active branch dedicated to one purpose: training sea creatures for war. If that sounds awesome, that’s because it is. Most commonly, bottlenose dolphins are trained to detect underwater mines, and then alert a nearby patrol of their presence.

In Seattle, dolphins and California sea lions are also trained to detect human intruders. When a dolphin spots a swimmer, it will swim to the nearest Navy boat, after which a sea lion will approach with a metal cuff and lock it around the intruder’s leg. Truly.

The Soviet Union also supposedly had a military unit for wartime marine mammals, and would train dolphins to attack enemy ships by differentiating between the sound of the ships’ propellers. A few years ago the dolphins were sold to Iran to be stationed in the Persian Gulf, and have hilariously been dubbed mercenaries.

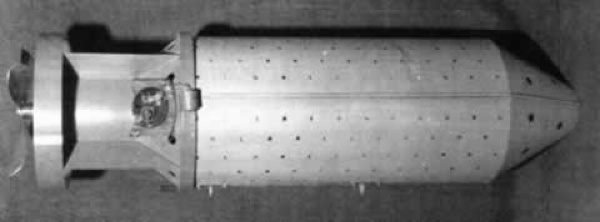

During World War II, military scientists on both sides of the struggle were actively searching for ways to get the upper hand. One idea that came from the US was the bat bomb, codenamed Project X-Ray.

Developed by Lytle S. Adams and actually approved for use by President Roosevelt, the bat bomb consisted of a large empty bombshell which was packed full of hibernating bats. At a certain altitude the bombshell would open and the bats, woken up by the warm air, would swarm out by the thousands.

Each bat had a small charge with seventeen grams of napalm attached to it. When the bats landed on the trees and houses of Japan, the tiny bombs would ignite and set everything on fire. The project was at one point one of America’s main strategies, and thousands of Mexican free-tailed bats were imported for the cause, but it was eventually shut down to invest more money in the atomic bomb.

One of the most visceral reminders of previous wars is the presence of uncounted land-mines scattered across old combat zones. These mines present a real danger to civilians, and it’s estimated that at least seventy countries still have forgotten mines buried beneath the soil.

Clearing away mines with human labor is time-consuming and deadly, so animals are often used for the purpose. Mongolia even reportedly offered the US 2,000 monkeys to help clear old minefields. But like humans, monkeys are still heavy enough to accidentally trigger a mine, which is why Charlotte D’Hulst is working on a genetically modified mouse that will be able to work with soldiers to accurately clear out more than 300 square meters of land in just a few hours.

The mice are modified to be able to detect scents 500 times fainter than normal mice, and are small enough that they won’t accidentally set off any mines in the process, potentially saving thousands of lives.

In the 1920s, Josef Stalin set in motion a plan to create a race of super soldiers by crossing human and chimpanzee genetics. He put his top veterinary scientist, Ilya Ivanov, to work on the project, tasking him with creating an “invincible human being, insensitive to pain.”

Ivanov went to work in French Guinea and there he attempted to impregnate female chimpanzees with human sperm—his own sperm. Records of the experiments suggest that he only used three chimps for the insemination project, although he brought ten others back to Russia with him, presumably before telling his wife, “For the experiments, I promise.”

The next stage of the experiment involved using ape sperm to impregnate a human female, but from what we can tell it never happened, because the only reproductive age ape they had access to died before they could get started.

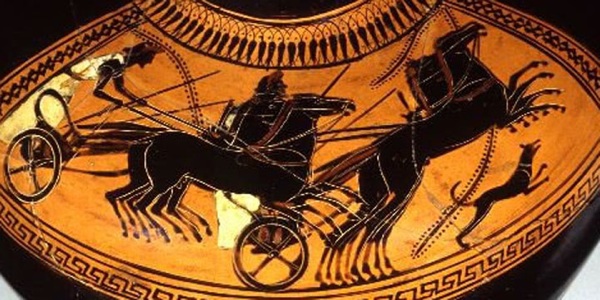

Although dogs are widely used in wars nowadays, they aren’t exactly weapons. In ancient Greece, however, warrior dogs might have been some of the most fierce opponents on the battlefield.

In the seventh century BC, the Greek city of Magnesia began to supplement their military forces with trained mastiffs, which can grow up to 250 pounds (113 kg). They would send the dogs into battle first to break up the troop formations, with the soldiers following behind to take advantage of the chaos. It may sound cruel, but keep in mind that these dogs were often treated like any other soldier, even to the point where they were fitted with suits of spiked armor to protect them in battle.

In 1994, the US Air Force started an initiative to develop non-lethal weapons for use in combat. One of the proposals (which was actually taken seriously) was entitled Harassing, Annoying, and ‘Bad Guy’ Identifying Chemicals. And it was, well, silly (not to mention vaguely offensive).

The entire report, which you can read here, identified several possible ways to drop chemical bombs on the bad guys that wouldn’t kill them, just sort of make them annoyed. For example, one such bomb would contain pheromones to attract bees or wasps to sting the enemy soldiers. Another chemical would inflict the enemy with “severe and lasting halitosis (bad breath).”

Finally, category #3 suggests using strong aphrodisiacs that “caused homosexual behavior.” In other words, the Air Force—at one point—considered making a gay bomb.

As any historian will tell you, Hannibal was a pretty decent military general. His strategic genius played a decisive role in the Punic Wars and put a huge thorn in Rome’s monolithic side for years. Hannibal is probably most famous for leading an invasion force (elephants and all) across the supposedly impassable Alps to attack Rome from inland where they least expected it, like a pre-Christ Lawrence of Arabia, but his most bizarrely creative strategy was yet to come.

Here’s the short version: Years after the Punic Wars, Hannibal was waging his own battle against Eumenes II, king of Pergamon. It was a boat battle, and Hannibal was outnumbered. But he came prepared—he had already figured out which ship carried the king, so as soon as his own ships were in range he immediately began launching jars full of venomous snakes directly onto that one ship, ignoring the rest of the fleet. The king freaked, turned, and fled, and the rest of the ships followed.

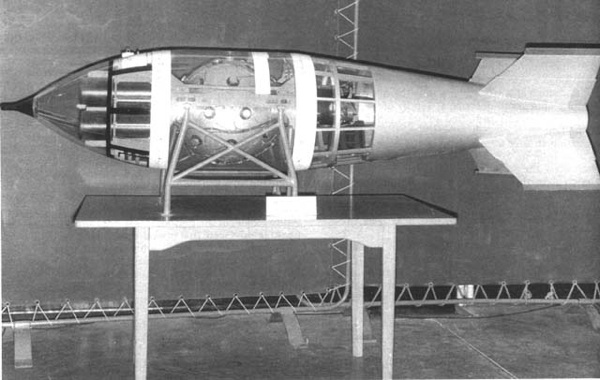

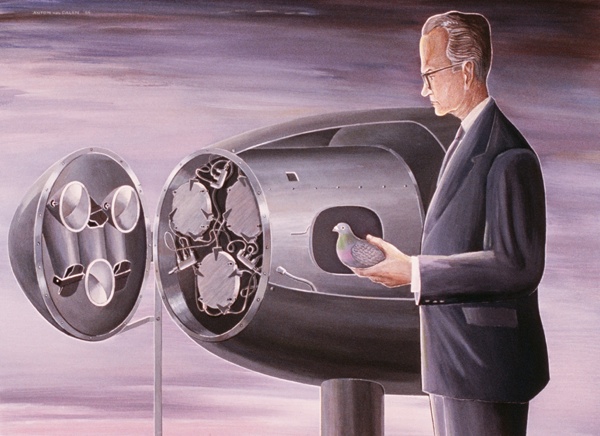

Another misguided World War II idea, Project Pigeon was a military plan to place pigeons inside the nose cone of a missile in order to guide it towards the right target. This was before the era of guided missiles, and it received a lot of attention from the US military.

The plan was to create a specialized nose cone that would fit onto a Pelican missile. Each cone had three compartments that would house trained pigeons and a screen that showed the path of the missile. As the missile fell towards its target, the pigeons would peck at the screen and align the missile in the right direction. The pigeons were trained beforehand to recognize the target, so if it was off-center—such as when the missile veered off course—the controls would correct until all three pigeons were pecking at the center of the screen, keeping the target dead-center ahead.

After some early funding, the project was nixed for being too impractical, although it would make a great Pixar movie.