Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

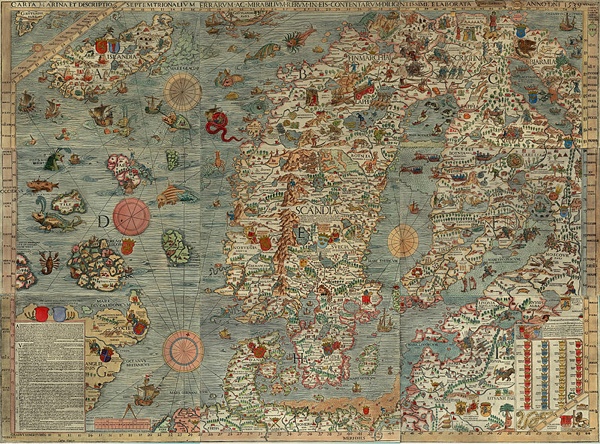

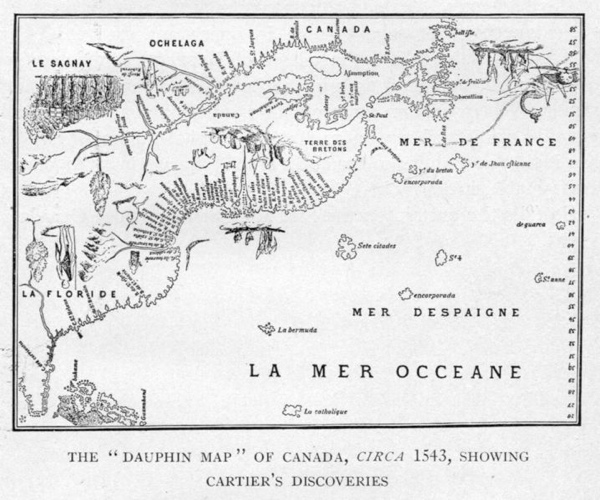

10 Phantom Islands

Last year (2012), a phantom island appeared on Google Earth, just north of New Caledonia in the South Pacific. They aren’t simply figments of the medieval imagination. Phantom islands are different from mythical lands, although as we’ll see, sometimes geography and fable get confused. All these islands once existed on maps and geographers believed they were real. Some were simple errors of fact that were later put right while others turned out to be pure fabrications. All of them had an effect on peoples’ consciousness.

Around 325 B.C., the Greek navigator Pytheas left his home port of Massalia (present day Marseilles), sailed into the Atlantic and turned north. He was the first classical writer to describe Britain, which he called Britannia, or Pritannia, and an island to the north of it he called Thule.

Unfortunately Pytheas’ original account is lost and all we have are commentaries on it by the geographer Strabo and other classical writers. Strabo thought Thule was an invention but he also thought Pytheas’ description of the seas north of the island being choked with ice was nonsense. Ptolemy added Thule to his map of the world in his atlas, Geographia which he published around A.D. 100. After the book was translated by Florentine scholars in the 1410s, Thule regularly appeared as a large island north of Britain on maps well into the to 17th century. Scholars believe that if Pytheas did sail north of Britain and discovered an island it was either one of the Shetlands, the Faroes, Iceland or even the coast of Norway.

Around A.D. 530, the Irish monk Brendan and his followers (the number varies from eighteen to 150) set out across the Atlantic to evangelize and search for Paradise. For seven years they lived on an island with a perfect climate, happy inhabitants and abundant nature. We think this voyage happened, which is to say that Saint Brendan and some fellow monks left Ireland, although the earliest accounts of it appear three hundred years later.

St Brendan’s Isle appears on the most famous map of the Medieval era, the Hereford Mappa Mundi, but more importantly it was a common feature on portolan charts, which were intended to be accurate charts for sailors. It also appeared on 17th century maps by Mercator and Ortelius and in the 1707 De Lisle map. Generally it was located west of the Canaries. There’s a feeling that by the Age of the Enlightenment mapmakers were willing to admit the island didn’t exist but that didn’t stop them wanting to believe in it.

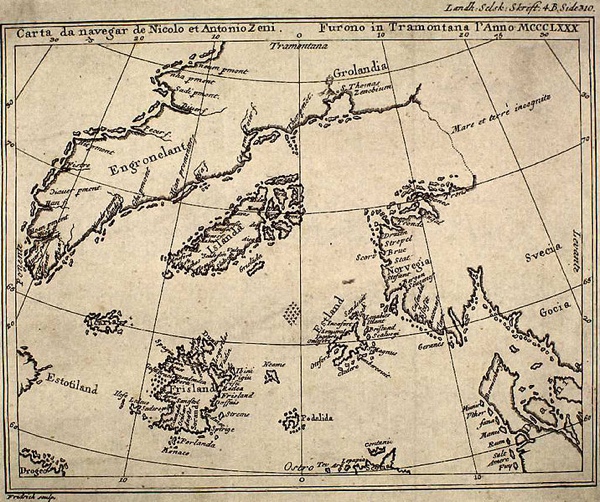

In 1558 the Venetian Nicolo Zeno published a map and letters he said came from two ancestors, Antonio and another Nicolo, who had navigated through the North Atlantic around 1400. The letters were mostly written by the first Nicolo to Antonio from an island called Frisland. On the map, Frisland was roughly halfway between the north-eastern tip of Scotland and Norway. Despite sporadic warfare with some neighboring islands and Greenland, Nicolo was doing alright for himself and encouraged Antonio to come and join him.

The letters were considered dubious when they were first published but that didn’t stop respectable cartographers adding Frisland to their own maps, often where Zeno said it was but also much further west so it was almost part of North America. A few maps include named bays, mountain ranges and towns.

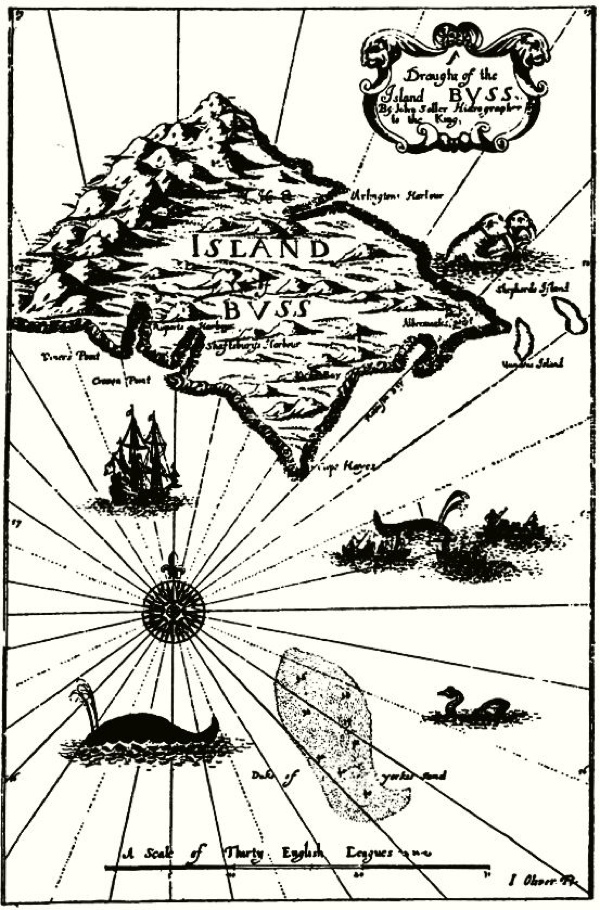

The search for a north-west passage from Europe to Asia began in earnest in 1576 when Martin Frobisher set out to find it (there had been earlier attempts). On his second expedition, one of the ships, the Emmanuel, sailed by an island the captain, James Newton, described as “seeming to be fruiteful, full of woods, and a champion countrie”. The island was named Buss, after the type of ship the Emmanuel was. (Somebody on board lacked an imagination. It’s like calling a place ‘four door sedan’ because you drove by it in one.)

Buss was placed on maps but despite several searches it wasn’t until 1671 that another British sailor, Thomas Shepard landed on it. He named several places in honor of his patrons at the Hudson Bay Company. Shepard made a return voyage to find the island and couldn’t. Buss soon vanished from sight again and the common theory was that it must have sunk beneath the waves. By the middle of the 19th century cartographers had come to accept it didn’t exist and left it off maps.

So what had Shepard and the crew of the Emmanuel seen? Given that longitude couldn’t be accurately charted in the 17th century, it is likely that Frobisher and Shepard saw different places they thought were the same and these places were either promontories of Greenland or islands that had already been charted. An alternative is that Buss Island does have the remarkable capability to rise and fall beneath the waves and will re-emerge soon.

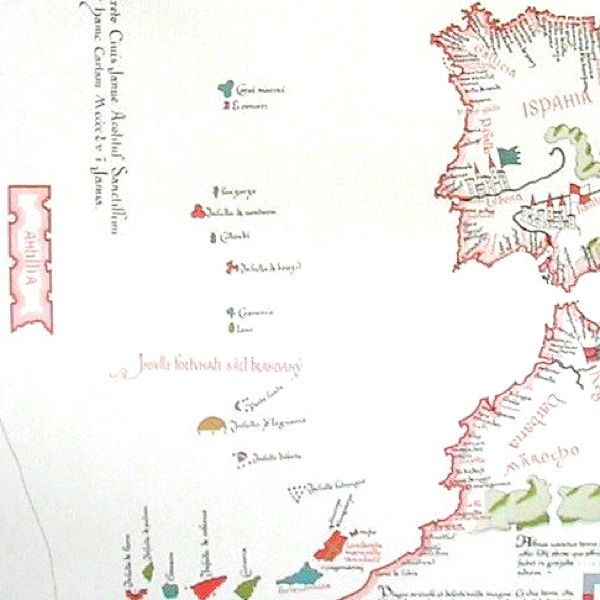

During the Middle Ages, as Islam became more powerful and the Church more corrupt, the notion that somewhere out in the Atlantic was an island where Christianity remained pure sounded awfully attractive. According to legend, when the Muslims invaded the Iberian peninsular in A.D. 711, a group of bishops took their flocks and sailed out into the Atlantic where they found an island and settled there. They called it Antillia or the Island of the Seven Cities. It was a Christian utopia where the people were blessed and so was nature.

The island is the first on this list to have existed in the imagination before it appeared on maps. During the 15th century it was commonly placed in the middle of the Atlantic, halfway between Europe and Asia. The discovery and mapping of the American coast didn’t entirely kill off the idea of Antillia. Some post-Columbus maps still included it. In his 1530 book De Orbe Novo, the Spanish historian Peter Martyr d’Anghiera claimed that a traveller who had spent some time in Antillia stayed with Columbus and gave him valuable information before his 1492 voyage.

If a paradise like Antillia or Saint Brendan’s Isle sounded credible in the medieval imagination so did its opposite, an island haunted by demons. In fact there were two; Satanazes, which usually lay a little to the north of Antillia, and the Isle of Demons off Newfoundland, which first appeared on 16th century maps. The two were sometimes confused although the first began to lose its credibility with the discovery of America and the second has the story of Marguerite de La Rocque to give it the germ of truth.

In 1542 she sailed with Jean-François de La Rocque, variously described as her husband, her uncle or even her cousin, to New France (French Canada). On the voyage she became pregnant to one of the sailors and along with her lady-in-waiting they were abandoned on the Island of Demons. That is to say, they were marooned on an island that only later became identified as the Isle of Demons. The lover, the servant and Marguerite’s child soon died and for the next two years she wandered the island, constantly under attack from the devils that inhabited it. Eventually some Basque fishermen found her and brought her back to Europe. In France she met Queen Marguerite de Navarre who took her account and turned it into a popular romance.

Somewhere between what actually happened and Queen Marguerite’s version, the details became distorted and enhanced. Were the demons in La Rocque’s imagination, were they Native Americans, conflations of both, or were they actually a later addition to fit in with the name of the place she was left on? That island certainly existed and it was close enough in location to the legendary Island of Demons to become one and the same.

Hy Brasil was a magical place off the Irish coast, hidden under dense mists except for one day every seven years. It bore more than passing resemblance to Saint Brendan’s Isle and Antillia in that beneath the mists the sun shone every day and the inhabitants had all they could ask for. It first appeared on portolan charts in the early 14th century and in 1498 John Cabot set out on an expedition to find it. Naturally he was unsuccessful but there are reports from well into the 17th century by people who claimed to have visited it. In 1674 John Nisbet was returning to Ireland from France when dense fogs forced him to anchor off an island. Four sailors went ashore and spent the day in the company of an old man who was so pleased for company he gave them several sacks of gold.

The two great cartographers of the late Renaissance, Abraham Ortelius and Gerhard Mercator, included Hy Brasil on their maps of Ireland. In fairness to them, they were working off received knowledge so if a sufficient number of reports and earlier maps claimed there was an island off the Irish coast they were inclined to put one in. By the 18th century it had pretty much disappeared from maps although there were still occasional claims by sailors to have visited it.

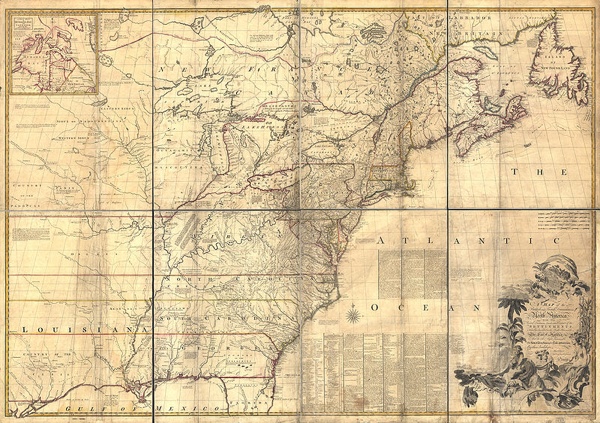

In 1783 this much was known about Lake Superior: it was big and it straddled the boundary between the USA and Canada that needed to be agreed on for the Paris Treaty between America and Britain to take effect. It was entirely believable that two large islands could exist in the middle of the lake, especially as they appeared on otherwise geographically accurate maps being used in the treaty negotiations. Even better, if the boundary ran north of the islands it was consistent with the one drawn on the land. So two parcels of land were handed to America; it was just a matter of finding them.

The islands had been named in the 1720s after Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain and French Secretary of the Navy. The theory is that French officers thought that adding them to official maps would sufficiently flatter the Count and he’d keep channelling funds towards exploration. He died in 1720, which was lucky because if he’d found out they were invented, heads would have literally rolled. It wasn’t until the 1820s that their non-existence was established, by which time the Louisiana Purchase had gone through and America wasn’t too bothered by the loss of lands that were imaginary in the first place.

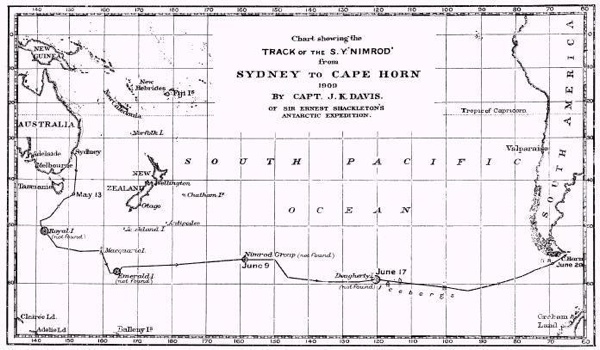

By the late 18th century the focus of exploration had shifted from the North Atlantic to the South Pacific. Though sailors made rapturous claims about Tahiti being a paradise, the search was on for more practical qualities, like timber, minerals or even an island that could provide a decent staging post for ships sailing between South America and Australia. By this time the problem of recording longitude had also been solved and accurate coordinates could be entered in ships’ logs. If a captain reported a previously uncharted island of sufficient size the claim was taken seriously and expeditions sent out to find it. Emerald Island sounds enticing—a name you might give to a really bad TV show or a tract housing development. It was called that after the ship that sealer William Eliot was captaining in 1821 when he sighted it.

The chart above shows the route of the 1909 expedition by Captain John King Davis in the Nimrod, the ship Ernest Shackleton used in his exploration of Antarctica. The phantom Nimrod Islands were named after an earlier ship of the same name from where they were sighted in 1828. Notice that the 1909 ship has gone to the exact locations where Emerald, Dougherty and the Nimrod Islands were supposed to be. Though Antarctica barely appears on the chart they were in a region close enough to receive its worst weather and as noted off Dougherty Island, icebergs were a problem. It seems likely that Eliot and the earlier Nimrod saw a Fata Morgana, a mirage prevalent in the polar regions that distorts distant objects and makes them appear as landforms. It wasn’t until the 1940s that Emerald and the Nimrod Islands were classified as phantoms. They still appeared on some maps up till then.

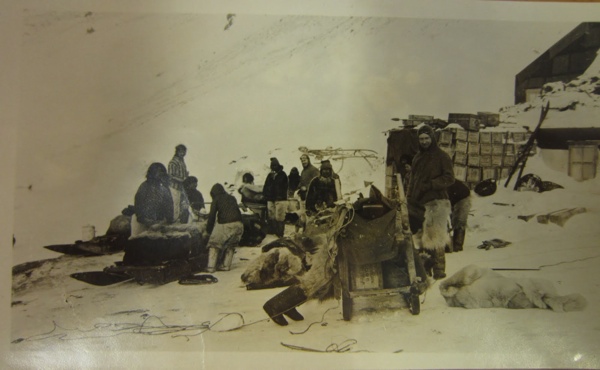

Is a phantom island worth killing for? In 1906 Robert Peary saw a large landmass off Ellesmere Island in the Arctic, which he named Crocker Land after one of his financial backers. Although there are accusations that Peary was perpetrating a hoax it is also possible he saw a Fata Morgana. (It shouldn’t be confused with the Croker Hills, which arctic explorer John Ross saw in 1816 and named after the Secretary of the Admiralty. They also turned out to be a mirage.)

In 1913 an expedition under Donald Baxter MacMillan from the American Museum of Natural History set out to find Crocker Land. He was excited at the prospect of discovering new plants, animals and even a new race of people. Like so many arctic expeditions, this one quickly hit worse conditions than had been expected. Frostbite and illness forced several members to return to the base camp. What was more, the local Inuit people, who knew what they were talking about, insisted there was no such landmass. As the situation became grim, MacMillan sent engineer Fitzhugh Green and Inuit guide Piugaattoq out to reconnoitre the land. At some point Green shot Piugaattoq and killed him. He would later claim he thought the guide was trying to escape with the dog team but before that the other expedition members agreed to the story that Piugaattoq fell into a crevice. Small justice, but the Macmillan team would be stranded in the arctic for four years. Paradoxically, the expedition was a complete disaster and the photographic records of Inuit people are considered its only real achievement.

John Toohey is the author of Captain Bligh’s Portable Nightmare (probably out of print) and Quiros (Definitely out of print). He is a photo-historian and author of the blog One Man’s Treasure.