Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

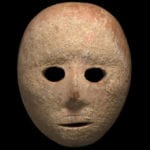

8 Recently Discovered Medieval Vampire Burials

The mythology of vampires is well-known throughout the world. Most countries have some variation on the vampire legend. Remarkably similar, too, are the ways in which vampires can be dispatched, or at least prevented from rising from the grave to plague the living. Modern science has usually dismissed these tales as folklore, however, recent evidence has emerged showing that our ancestors did indeed take these stories seriously. Over the past few decades, an increasing number of medieval burials have been excavated showing incredible brutality performed on the corpses that exactly matches the methods folklore said must be used to keep a vampire safely in its grave. And these graves are not only being found in the vampire’s traditional home of Eastern Europe and the Balkans, but in Western Europe too. Here are 8 of the best-attested cases of medieval vampire burial

In 1991, an archaeological investigation of the ancient church of the Holy Trinity in Prostejov discovered a crypt burial in the presbytery. The body had been buried in a coffin reinforced with iron bars, held to be one method of keeping a vampire buried, since vampires allegedly could not tolerate the touch of iron. In addition, stones had been placed on the victim’s legs, and the torso severed from the legs. The find has been dated to the 16th century. The burial is considered somewhat unusual because of its location in a church, but it has been argued that the extra sanctity of the church may have been thought by those who buried the victim to have been more likely to have kept the corpse in its grave.

In 2009, at Drawsko in Poland, an archaeological investigation of a medieval cemetery turned up something quite unexpected. Three graves were discovered in which the bodies had been subjected to very unusual treatment post-mortem. Two bodies of middle-aged adults had iron sickles placed on their throats. The body of a younger adult had been tied up and had a heavy stone placed upon his throat. This is in keeping with folklore, traditionally sharp iron implements being held to be anathema to vampires, hence the placement of the sickles as a measure to ensure that the alleged vampire would not rise again. Another method of keeping a suspected vampire in their grave was believed to be the placement of heavy weights upon the body, and the positioning of heavy stones upon bodies has been found in a number of vampire burials. The cemetery has not been fully excavated and archaeologists expect to find similar burials in future years.

In 1994, on the Greek island of Lesbos, near the city of Mytilene, archaeologists investigating an old Turkish cemetery found a medieval skeleton buried in a crypt hollowed out of an ancient city wall. This was not an unusual discovery, however, the post-mortem treatment of this body was very much unexpected. The corpse had been literally nailed down in its grave, with heavy iron spikes driven through the neck, pelvis and ankle. The use of iron and the practice of staking down a corpse are both well-attested in vampire folklore. The body was almost certainly that of a Muslim, believed to be the first time a corpse of a person other than a Christian had been found treated in this fashion.

In the early 1990s, archaeologists found what is believed to be the first vampires’ graveyard—an entire cemetery of vampire burials. In Celakovice, about 30 kilometers north of Prague, 14 graves have been excavated so far with metal spikes driven through their bodies or heavy stones placed upon them. The graves are believed to date from the 11th or 12th century. Most of the victims were young adults, of both sexes. It appears that the victims all died at around the same time, possibly in a epidemic, but it is unclear why the villagers thought these individuals were at risk of becoming vampires.

One of the most well publicized cases of recent years, as a Google search will quickly show. Bulgaria is no stranger to vampire burials. More than 100 have been discovered in the past century, but the bulk of those were in remote rural areas. Sozopol is one of Bulgaria’s most popular Black Sea tourist resorts, so the discovery of two skeletons with iron spikes jammed through their bodies caused a sensation. The bodies are believed to about 700 years old, and were located buried near a former monastery. Archaeologists have confirmed that this practice was common in Bulgaria up until the 20th century, and Bulgaria subsequently has become the center of interest for those studying vampire burials.

As has already been noted, the discovery of vampire burials has been common in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, the heartland of vampire mythology. However, until recently, they were unknown in Western Europe. This is now changing, as archaeological examination of medieval cemeteries in the West is starting to reveal that people here were just as afraid of the dead returning to plague the living. A well publicized discovery in 2006 on the island of Lazaretto Nuovo near Venice confirmed that Italy had its own vampire burials. The skeleton of a woman dating from the 16th century was discovered in a cemetery of plague victims. She had had an a large brick rammed into her mouth prior to burial. This is in keeping with medieval folklore, which held that vampires literally chewed their way out of their burial shrouds, so preventing them from doing this was seen as an effective way of stopping them rising from the grave.

The vampire burial phenomenon struck even deeper into the West with the discovery of two skeletons at Kilteasheen in Ireland between 2005 and 2009. Officially described as “deviant” burials, the skeletons of a middle-aged man and a man in his twenties were discovered lying side by side with rocks rammed into their mouths. The discovery caused a sensation in Ireland and the UK and became the subject of a TV documentary released in 2011. It has been argued that the victims may have been considered plague-carriers rather than true vampires, because their early burial in the 8th century predates vampire legends in Europe, however, the vampire burial tag has since well and truly stuck in the public consciousness.

If complacent Britons had thought their ancestors were far too sophisticated to be taken in by vampire legends as primitive peasants in Eastern Europe had been, they were in for a shock. It was revealed in 2010 that a deviant burial had been found in the Nottinghamshire town of Southwell in 1959, attracting much publicity in the British media. A long-lost archaeological report compiled during construction of a new school detailed the discovery of a skeleton dating from between A.D. 550 and 700 with metal spikes jammed through heart, shoulders and ankles. The placement of a spike through the heart in particular attracted public interest because of its long association with vampires in myth and legend. Archaeologists have in fact thrown cold water over the idea the man was considered a vampire because the burial predates vampire legend in Europe, but the idea has seized the public imagination and inspired new research into vampirism in Britain.