Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

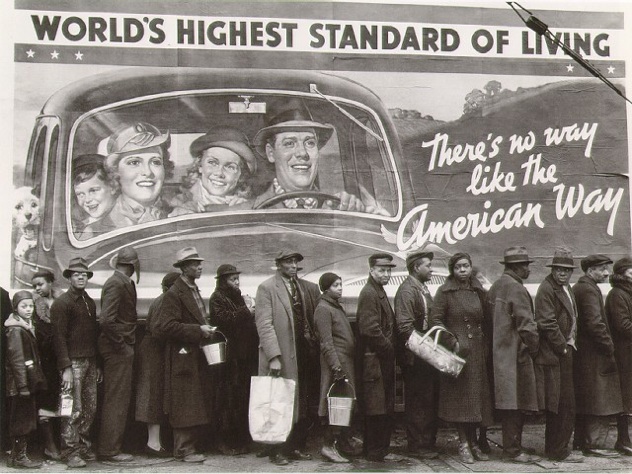

10 Shady Origins Of Consumerism In The US

Consumerism and the practice of flaunting one’s status through clothes, jewelry, and other things has existed since the dawn of civilization. Yet, the endless cycle of working to buy has never been more rampant than it is now. How did the United States, a nation founded on Puritan, non-materialistic tenants become filled with the biggest shoppers on the planet and end up occupying 29% of the World’s consumer market? As it turns out, Americans were carefully and systematically manipulated into becoming insatiable shoppers.

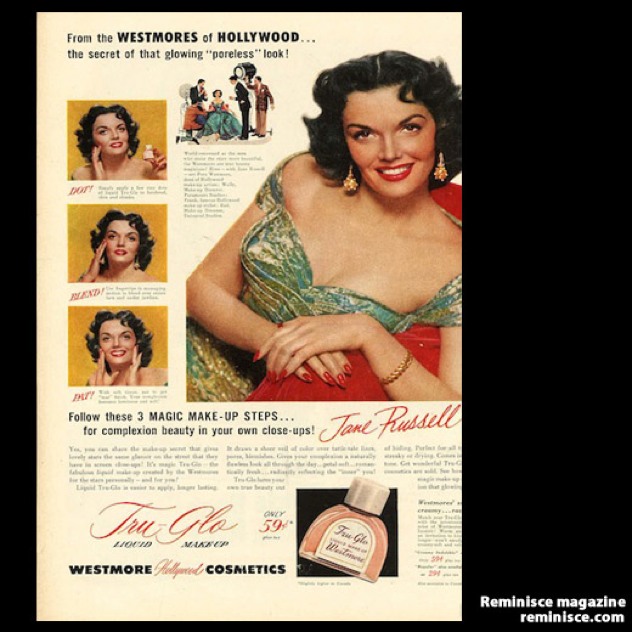

The man who is largely responsible for introducing advertising as we know it was none other than Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays. Bernays’, nicknamed the “father of public relations,” studied his uncle’s writings on psychology and group mentality and learned humans react to feelings not facts. With this knowledge, he saw an opportunity to capitalize on people’s subconscious desires by selling goods with the promise of delivering power, status, sex appeal, glamour, health, and other things with emotional connections. His uncle also taught him that humans often act irrationally when emotions are involved and can be led to believe objects are a symbol of their character. Bernays used these theories to manipulate people into buying products they didn’t necessarily need or want.

One of Bernay’s first widely known marketing campaigns was for the American Tobacco Company where he was tasked with attracting more female smokers. Of course, he had one major hurdle to overcome—it was 1928 and there was a longstanding taboo about women smoking in public. So, Bernays’ consulted a psychoanalyst to help him get at the root of the taboo and was told that cigarettes symbolized the penis. Bernays shrewdly decided to center the Lucky Strike campaign on female power and independence, by advertising cigarettes as “torches of freedom,” equating smoking to female equality. His advertising efforts caused a national stir and almost immediately made it acceptable for women to smoke.

Bernays dominated the marketing arena throughout much of the 20th century and is the reason why those in the US consider bacon and eggs the quintessential breakfast, why Ivory soap is preferred by doctors, and, according to some, is the reason why people believe water fluoridation is safe and beneficial. He had so many successful campaigns that “Life Magazine” named him one of the most influential Americans of the 20th century.

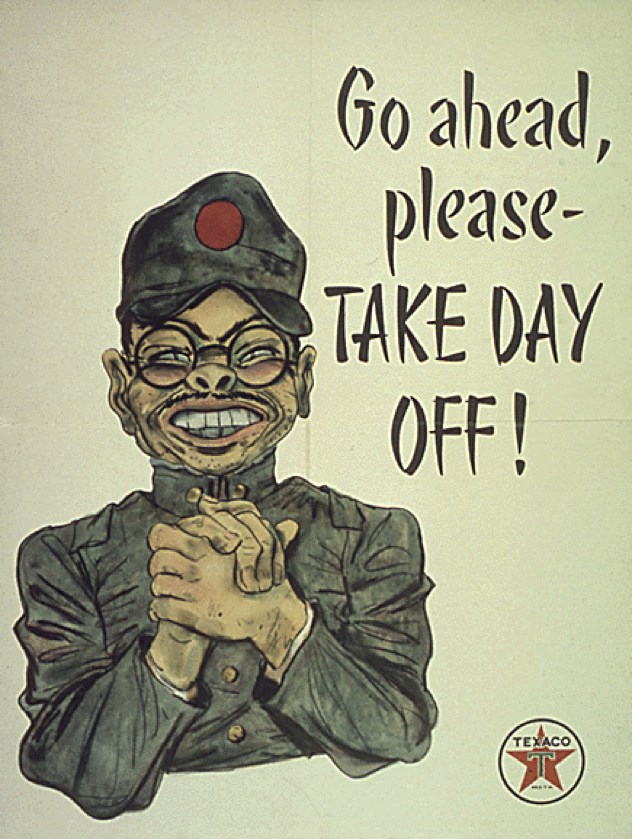

From the start, it seems the idea of a consumerist, malleable society was linked with government ambition. Some of Bernays’ earliest work was as a press agent for the American Committee on Public Information during World War I. In that position, he promoted President Woodrow Wilson as a liberator, spread the tenants of democracy, and was so accomplished he joined the President at the Paris Peace Accords in 1919.

After seeing the effectiveness of propaganda, those in authority weren’t too keen on putting the art of manipulation back in the bag, so to speak. So, even after the war, both the government and businesses continued to use propaganda as a way to control citizens, and occasionally the interests of the government and corporations aligned.

For example, manufacturers were worried the high production and sales they’d grown accustomed to would dwindle once the war was over. Naturally, they didn’t want to see diminishing profits, so they used Bernay’s advertising strategies to convince people to buy more by linking goods to unconscious desires. At the same time, many presidents touted the ‘buy, buy, buy,’ mantra in the hopes it would boost the economy. President Herbert Hoover said to Bernays, “You have taken over the job of creating desires and have transformed people into constantly moving happiness machines, machines which have become the key to economic progress.”

Once consumerism settled in as the basis for the American economy, those in power gradually quit seeing Americans as citizens, but regarded them, above all else, as consumers.

Indeed, it seems today’s leaders treat us like potential buyers, and instead of giving us well-formed, fact-based arguments, they offer sales pitch-esque communications and package their platforms as if they’re destined for the marketplace. In 2002, when George W. Bush’s chief of staff Andrew Card was asked why the administration waited months to explain the reasoning for invading Iraq, Card replied “You don’t roll out a new product in August.”

Overtime, the habit of referring to “citizens” as “consumers” became increasingly common, and now the terms are used interchangeably. This evolution, however, doesn’t sit well with everyone. According to a recent study conducted by Northwestern University, many folks take offense at being called a consumer, “as if their sole purpose and reason for existence on this planet is to consume—to eat, drink, use, watch, and buy stuff.” Interestingly, the study also found that being labeled a consumer automatically makes people behave more selfishly.

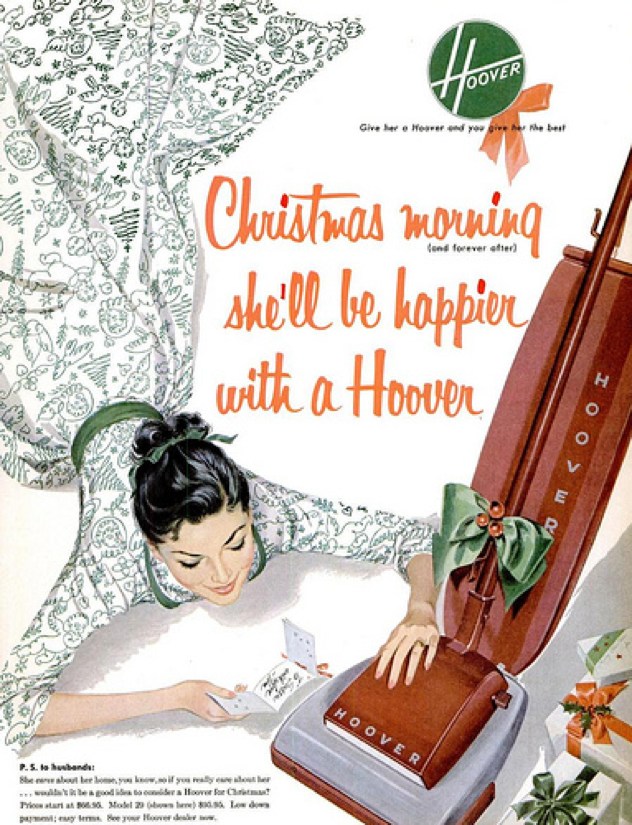

In an interview shown in the BBC documentary “The Century of Self” Bernays said the word “propaganda” developed a negative connotation after World War I and II, since it was associated with something Soviet Communists and Nazis used to perpetuate their command. To distinguish his profession Bernays quit calling his industry propaganda and renamed it “public relations.” Still, public relations was little more than a euphemism, as it continued to rely on the fundamentals of propaganda: half-truths, persuasion, and attempting to change public attitudes. Although advertisers weren’t coercing people into supporting a particular political party, they were using their messages to influence how citizens felt about clothes, cars, beauty, and everything in between.

Nowadays most of us know we can’t take any advertisement at face value. In other words, we understand celebrities are paid to carry a certain brand of bag, we see the Coke can placed blatantly front and center in our favorite TV shows, and we know cars are supposed to represent male sexuality. Yet, even knowing these ideals were completely manufactured, it’s nearly impossible to keep them from seeping into our own beliefs — that’s the strength of the propaganda.

Apparently, Bernays didn’t realize his form of marketing so closely resembled fascist strategies and was shocked to learn Joseph Goebbels, Hitlers Reich Minister of Propaganda, kept copies of Bernay’s writings and used them to engineer the rise of Nazism.

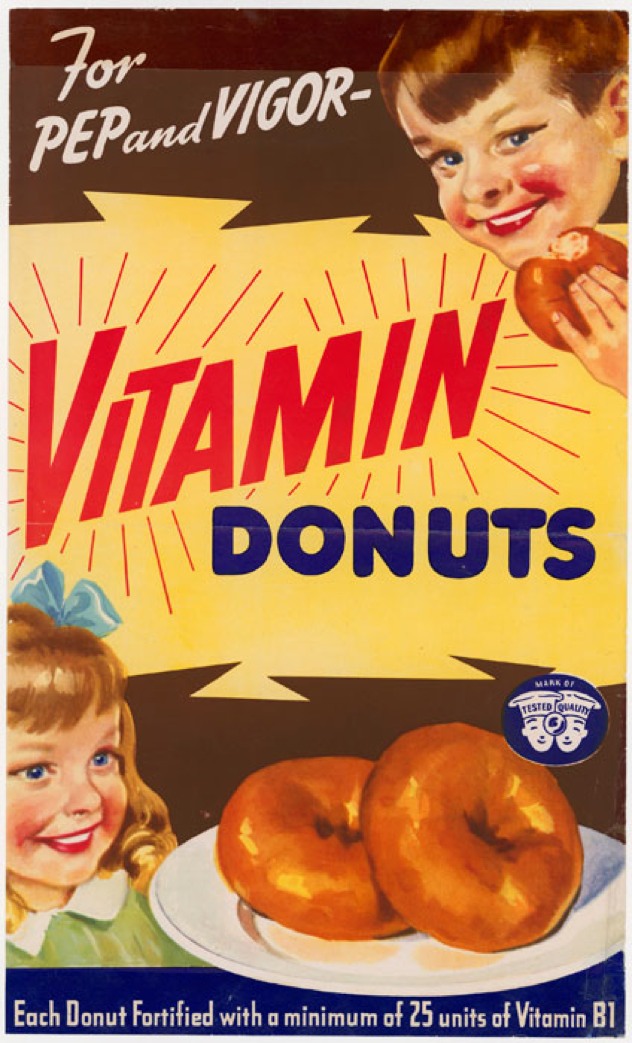

Early advertisers understood the only way to keep consumers buying was to ensure they were never wholly satisfied. Although most companies didn’t make shoddy products (although planned obsolescence is currently an issue), they did use ads to convince viewers they were somehow inferior if they didn’t have the newest, most expensive gizmo on the market.

Wall Street banker Paul Mazer made it clear when he said, “We must shift America from a needs- to a desires-culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old have been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America; man’s desires must overshadow his needs.”

It was no secret customer dissatisfaction was the goal for many manufacturers. Charles Kettering, director of General Motors, wrote an article for a 1929 magazine which he candidly titled “Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied.” In it, he tried to persuade readers that continual consumption was the only way to sustain the economy. He said, “You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times.”

While it may seem like it’s our economic duty to continually spend (and subsequently work harder), in truth we could all work a fraction of the time and still have enough goods and services to meet everyone’s needs. Secretary of labor James J. Davis discovered this fact in 1927 and discussed it in an interview with “Nations Business,” pointing out that America’s textile mills “could produce all the cloth needed in six months’ operation each year” and only 14% of the country’s shoe factories were needed to provide every citizen with footwear for a year. Later in the interview it was suggested that all the world’s needs could be met by only three work days a week.

Facts aside, intuitively it seems like we should be working significantly less than our ancestors. After all, we have machines, assembly lines, computers, the internet, and a wealth of technology meant to make our lives simpler, yet, according to an ABC News article, we are working longer hours than at any time since statistics have been kept, and Americans are working more than anyone else in the industrialized world.

So, what gives? Why isn’t technology making our lives easier and why aren’t we all jumping on board the three day work week that was shown viable in 1927? Unfortunately, it’s all done for the sake of business profits. Working employees everyday and getting greater numbers of products to market is more profitable for business owners than just meeting everyone’s needs—that is, of course, if they can convince people to buy the products. But, thanks to Bernays and his followers, corporations know how to turn citizens into consumers, trigger their unconscious cravings, and make them purchase unnecessary products.

In his later life, Sigmund Freud became increasingly withdrawn from the world as he felt humans were innately evil and civilization was a largely ineffective construct meant to restrain our animalistic sides. Bernays and others latched onto this notion and felt it was their obligation to direct the masses towards what was best for society.

Bernays’ own daughter said her father felt the public’s judgment was not to be relied upon since people could very easily vote for the wrong man or want the wrong thing, so they had to “be guided from above” by a group of enlightened despots. As expected, Bernays deemed himself one of the enlightened and used his advertising messages to influence the people towards his will.

Walter Lippmann, a 1920s political commentator, had similar notions and believed people would operate under a mob mentality if not adequately governed by the intellectually elite. He argued that the average person had too many limitations (selfishness, preconceptions, limited social contact, prejudices, etc.) to make socially responsible decisions. Such philosophies gave those in power the ability to justify their manipulative tactics.

For the elites to maintain dominance over the average man and keep him on the perpetual work/ buy machine, they had to link consumption with an emotion nearly all Americans share: patriotism. And nothing is a greater symbol of Americanism than democracy.

Those who judged themselves enlightened, like Bernays, saw nothing wrong with manipulating the public into thinking consumption was a democratic necessity. In fact, he may have believed it himself, as he said, “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in a democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country… we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons… who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.”

The idea of consumption being fundamental to consumerism became so ingrained that today when someone speaks of anti-consumerism or anti-capitalism they are immediately pegged as a socialist or communist. Yet, others would argue a capitalistic, consumption-based society is by definition undemocratic because it perpetuates low wages and creates class divisions which prevent all citizens from having an equal say in the decisions affecting their lives. In other words, those with the most money have the most power and influence.

There were a few who spoke out about how unbridled consumerism led by corporations could result in excessive waste, depletion of resources, and a submissive working class.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt particularly stood out in his distrust of a corporate-run economy. In his 1936 “Acceptance Speech for the Democratic Nomination for President” he said, “It was natural and perhaps human that the privileged princes of these new economic dynasties, thirsting for power, reached out for control over government itself. They created a new despotism and wrapped it in the robes of legal sanction. In its service new mercenaries sought to regiment the people, their labor, and their property. And as a result the average man once more confronts the problem that faced the Minute Man.”

Fearing Roosevelt’s sentiments could undermine their influence, the industrial elite from corporations like General Motors, DuPont, and General Foods came together and formed the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). Together they started spreading the message that Roosevelt was running the country into debt and was responsible for the slow economy. In a 1936 internal memo, NAM was tasked with “re-selling all of the individual Joe Doakes on the advantages and benefits he enjoys under a competitive economy.” NAM packaged its message with the idea that sacrificing a free economy would lead to the handing over of all freedoms to the government, including free speech, religion, and press.

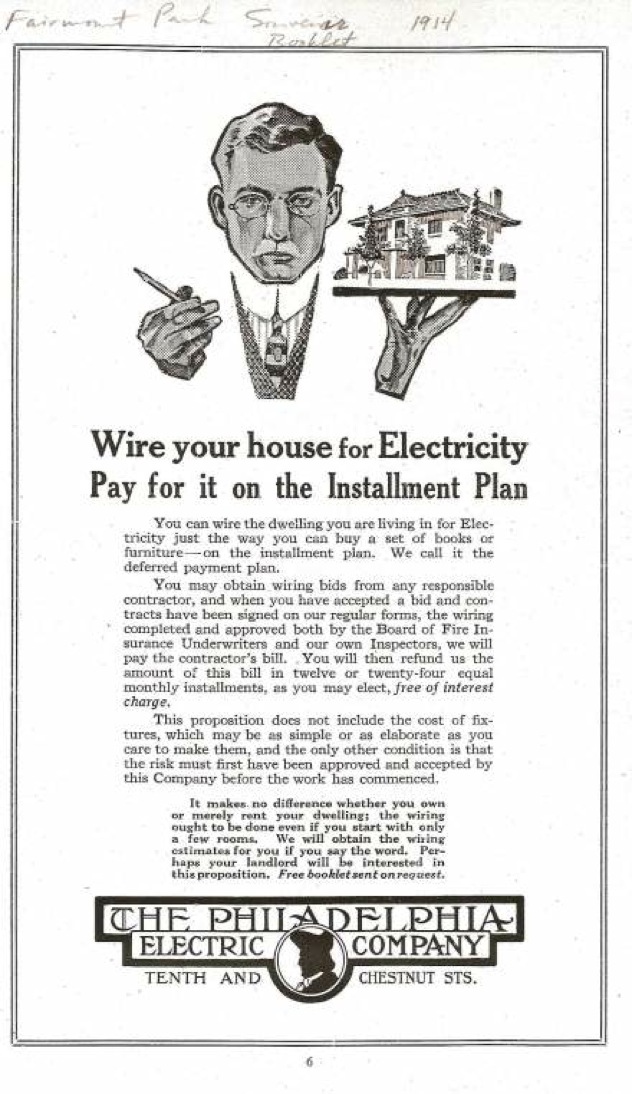

In the 1920s, manufacturers realized they could expand their profits even further by targeting a largely untapped market—the poor and lower-middle classes. Obviously these folks didn’t have much disposable income, so businesses came up with a sort of workaround: the installment plan. These plans allowed consumers to buy expensive goods by agreeing to pay for the product in increments over a set period of time. Often this setup resulted in the buyer paying far more than the product was actually worth, yet it made it possible for many more people to purchase costly items such as cars, appliances, furniture, washing machines, and other luxury goods.

Creditors, debtors, and installment plans were nothing new for the time, but being in debt always carried a certain stigma. Savvy advertisers knew they had to remove the shame of debt if they had any hope of the masses taking advantage of the installment programs. And so they did. “A small cash payment,” “convenient monthly payments,” “a reasonable down payment,” and other persuasive sayings, which are all too familiar today, became mainstream. In some publications the number of advertisements mentioning installment plans more than tripled through the 1920s. Also, the overwhelming success of installment buying in the auto industry (thanks in large part to GMACs marketing efforts) made it socially acceptable to use installment plans to buy other types of goods.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression that followed the roaring 1920s was more painful for those who participated in installment plans, since their lack of income also meant the repossession of many of their belongings.

Unfortunately, it seems neither businesses nor citizens have learned from the mistakes of the 1920s and ’30s, since we’re still persuaded to rack up debt and live outside our means.

Content and copy writer by day and list writer by night, S.Grant enjoys exploring the bizarre, unusual, and topics that hide in plain sight. Contact S.Grant here.