Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Most Bizarre Scientific Stories

Some of the most mind-blowing experiments in history weren’t, technically speaking, successful—many either failed to achieve what they intended, or achieved something far stranger than the experimenter could have ever imagined. Below are some of the weirdest, creepiest, and most bizarre experiments in recorded (and in some cases, unrecorded) history.

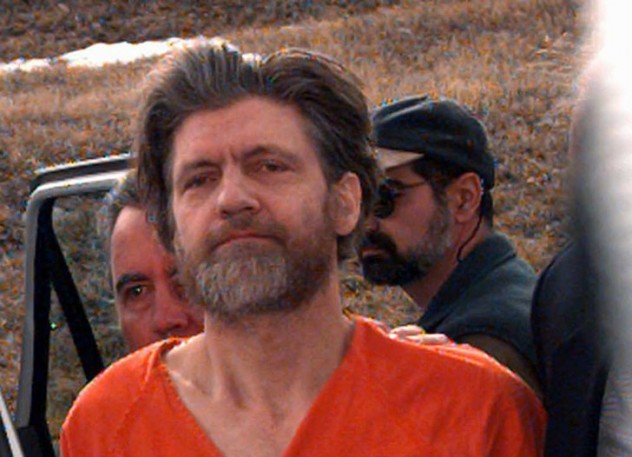

10 The CIA Created The Unabomber

The Unabomber, also known as Ted Kaczynski, is a man currently serving a life sentence in prison for killing three people and injuring 23 others with a series of bombings. What many people don’t know is that before his attacks, Kaczynski was mainly recognized for his incredible genius.

As a child, Kaczynski skipped both sixth and 11th grade, and began studying as an undergraduate at Harvard when he was only 16. He was the subject of much bullying when he was younger due to his lack of social skills, but many of his colleagues realized his mathematical intelligence unlike anything they’d ever seen. As an undergraduate, Kaczynski took part in a psychologically damaging experiment done by the CIA as part of the behavioral engineering project MKUltra. The study was run by Dr. Henry Murray, who had each of his 22 subjects write an essay detailing their dreams and aspirations. The students were then taken to a room where electrodes were attached to them to monitor their vitals as they were subjected to extremely personal, stressful, and brutal critiques about the essays they had written.

Following the psychological attacks, the participants were forced to watch the videos of themselves being verbally and psychologically assaulted multiple times. Kaczynski is claimed to have had the worst physiological reaction to being interrogated. These experiments, paired with his lack of social skills and memories of being bullied as a child, caused Kaczynski to suffer from horrible nightmares that eventually drove him to move into isolation outside Lincoln, Montana.

In Lincoln, Kaczynski built his own cabin and began living simply, without electricity or running water. He set out to become self-sufficient and create primitive technologies by hand. He found his work was limited by the development and industry that was destroying the environment around him. After he found his favorite spot in the wilderness destroyed by industrialization, Kaczynski had reached his breaking point.

Ted began to believe that technology was evil and so were those promoting it. Many believe Kaczynski’s participation in the Harvard study is what later influenced him to send letter bombs to multiple establishments, including airports and universities, in an attempt to get the public’s attention. Kaczynski became a big target for the FBI after his 18-year reign of terror over those whom he believed were promoting anti-human technology that was destroying the world. In 1995, Kaczynski demanded that newspapers publish his 50-page manifesto called Industrial Society and Its Future. He eventually became known as the Unabomber, killing three people and causing injuries to 23 more during his 18 years of mental breakdown.

9 LSD French Hysteria

The town of Pont-Saint Esprit in France isn’t known for much—aside from an odd and widespread outbreak of psychosis on August 15, 1951. Many believe this outbreak (involving over 500 people) to be the result of an experiment carried out by the CIA’s own program, MKUltra.

Supposedly, a report issued in 1949 had been found regarding the United States’ experimentation with the newly discovered drug, LSD. These mass hallucinations ranged from people believing they were being eaten by snakes to people jumping out of windows because they thought they were airplanes. At the time, the US believed it could harness the power of LSD to cause mass hallucinations in their enemies, damaging their ability to respond to attacks.

The hysteria ended with the death of five people and the suicide of at least two others, with no apparent explanation. The hallucination was deemed to be widespread ergot poison by the Sandoz Chemical Company near Pont-Saint Esprit. It is believed, however that the chemical company had been working alongside the CIA to produce mass amounts of LSD for their experimentation with it.

Regardless of the cause, the massive hallucinogenic outbreak that occurred in this little French town is mired in unanswered questions.

8 Beauty And Brains

Hedy Lamarr is most known for her beauty on the silver screen as an actress during the golden age of MGM, but few know that her immense beauty was matched by her equally immense brains.

Hedy Lamarr is most known for her beauty on the silver screen as an actress during the golden age of MGM, but few know that her immense beauty was matched by her equally immense brains.

In the midst of her acting career in the 1940s, Lamarr teamed up with George Antheil with the idea to create a secret communication system. Lamarr was a talented mathematician and, with the help of Antheil, she was able to create and patent an early version of frequency hopping using piano players. She hoped her invention could be used by the military to make radio-guided torpedoes less detectable and harder to jam. Despite securing a patent and pitching the idea to the US Navy, few men of the day took Lamarr or her ingenious idea seriously because of her reputation as an actress.

The idea of frequency hopping that she had developed using a piano roll to change between 88 frequencies was finally picked up by the Navy in 1962. By then, the patent had expired along with Lamarr’s hope for getting any recognition. Today, Lamarr’s invention is widely used as a basis for things such as Bluetooth and Wi-Fi—but she received little credit for her idea until 1997.

7 Suicide Song

What if there was a song so depressing, it could cause you to commit suicide? According to many believers, there is: Gloomy Sunday was composed by Rezso Seress in 1933. Laszlo Javor wrote its lyrics and it was first recorded by Pal Kalmar in 1935.

While it was being written, the United States was in the grip of the Great Depression with a fascist government coming to power in Seress’ native country of Hungary. His lyrics reflect his loss of faith in man and the injustices that were being committed. The song is an unusually sad prayer to God to have mercy on the bad people in the world, which is why Seress had a difficult time finding someone willing to publish it. Laszlo Javor, who had just broken up with his fiancée, later published the song with music and lyrics. Nineteen suicides in Hungary and the United States have been linked to this song in some way or another, including Seress’ own failed attempt to throw himself out a window (though he later succeeded in choking himself with a wire in the hospital).

The creepily melancholy song had been banned from Hungarian (and American) radio stations for worsening the wartime morale. The links between the deaths include suicides right after listening to the song, references to it in suicide notes, corpses holding the sheet music, or having it played on their gramophones.

6 Haber’s Rule

Most know Fritz Haber for his Nobel Prize-winning development of synthesized ammonia for fertilizers and explosives, but few know about his evil work for Germany during World War I. Many scientists of the day saw World War I as not only a war between countries, but between the chemists that represented them when it came to developing new and deadly techniques for chemical warfare. Also known as the “father of chemical warfare,” Haber played a major role in developing chemical weapons. Haber was able to develop uses for deadly chlorine gas that, because of its density, would settle in the enemies’ trenches, choking and burning them to death. He also discovered that long exposure to low concentrations of deadly gases had the same effects as short periods with high exposure. He was able to calculate the relationship between exposure and time, calling the equation “The Haber Rule.”

Haber was proud to serve for Germany and was even promoted to captain by the Kaiser for his work in chemical warfare. Haber believed gas warfare was humane, claiming that death is death regardless of the means by which it was caused. But his wife, Clara Immerwahr (the first female chemist to ever achieve a PhD at the University of Breslau), strongly opposed his involvement in gas warfare. She eventually committed suicide after witnessing the horrid effects the chlorine gas had at the Battle of Ypres.

As World War II began, the Nazis approached Haber, a Jew, offering him funding to continue his chemical weaponry research. Haber declined and fled to Cambridge, England with his assistant. While he was there, it was said that Ernest Rutherford refused to shake Haber’s hand for what he had done in the field of chemical warfare. During the 1920s, researchers at Haber’s institutes continued developing several forms of deadly chemical warfare including the cyanide formula Zyklon A, which was later developed into Zyklon B for gas chambers at Nazi concentration camps.

5 Missing Cosmonauts

Most think that Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space, but is that true? As the space race boomed between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, both countries were going to great lengths to be the first to cross that great boundary. Many of the attempts made by both the United States and Soviet Union ended in failure, and because of this, most of those stories have been destroyed. It’s believed that prior to Gagarin’s successful attempt, two or more cosmonauts had been sent into space—never to return.

In order to avoid the bad publicity, most information on any “lost” cosmonauts has been covered up. However, The Torre Bert listening station in Italy has captured several recordings of the almost mythical figures. The first was of a very frightened and confused woman talking about her craft failing upon re-entry—She is believed to be saying “Isn’t this dangerous? Talk to me! Our transmission begins now. I feel hot. I can see a flame. Am I going to crash? Yes. I feel hot, I will re-enter–” and then the transmission cuts out. (Some believe this to be a hoax because radio signals cannot be transmitted during re-entry). Another recording picked up sounds of heavy breathing and other noises that lead some to believe Sputnik 7 was a manned flight and that the pilot, Gennady Mikhailov, died of heart failure during orbit.

The Torre Bert heard three more signals, one from a couple aboard Lunik affirming that “Everything is satisfactory, we are orbiting the Earth” at regular intervals until an abrupt shift to garbled and frantic communication on February 24th, a description of something very large outside their ship, and then silence. The next transmission came in as an SOS signal that seemed to be fading as the cosmonaut drifted farther and farther from Earth. The final transmission received is believed to be from Alexey Belokonev frantically radioing “conditions growing worse—why don’t you answer? We are going slower. The world will never know about us.”

Whether or not the Soviets ever covered up a lost astronaut, it was certainly within their capabilities. For proof, look no further than the case of Grigori Nelyubov, a man dismissed from the Soviet space program, only to have all documentation about him destroyed (including his removal from a series of pictures documenting his membership in the program).

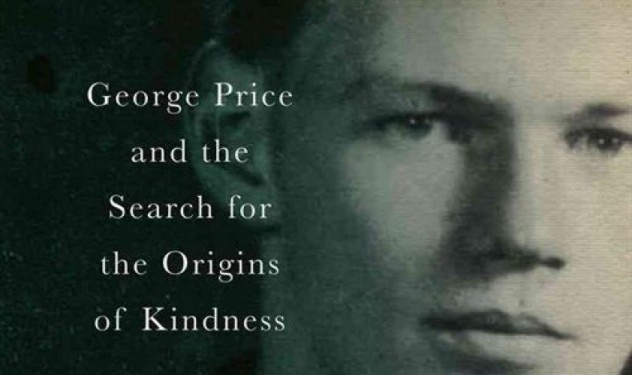

4 Killed By Kindness

George Price was a chemist and geneticist who moved to London in 1967 to do some work in theoretical biology. With no formal training in the fields of population genetics or statistics, Price was still able to formulate an equation that mathematically disproved the idea of true altruism. No theory had ever had the sheer number of applications in evolution, biology, and mathematics that Price’s theory on kin selection did. In a nutshell, his theory stated that people are most likely to show altruism to an organism whose genetic makeup is most similar to their own (like a parent or child perhaps) because in doing so, their genetic heritage would be most likely to live on.

George Price was a chemist and geneticist who moved to London in 1967 to do some work in theoretical biology. With no formal training in the fields of population genetics or statistics, Price was still able to formulate an equation that mathematically disproved the idea of true altruism. No theory had ever had the sheer number of applications in evolution, biology, and mathematics that Price’s theory on kin selection did. In a nutshell, his theory stated that people are most likely to show altruism to an organism whose genetic makeup is most similar to their own (like a parent or child perhaps) because in doing so, their genetic heritage would be most likely to live on.

Price also theorized that, in the same way an organism would “sacrifice” itself to further its genetic line, it would also sacrifice itself to eliminate others closely related to it if that meant that the organism’s genes would better propagate. The implication is that kindness is never truly selfless if it’s actually a survival adaptation.

As mind-blowing as that is, the more interesting part of the story is what the theory did to its creator: Price could not emotionally handle the idea that he belonged to an exclusively selfish species. He began partaking in increasingly random acts of kindness towards both strangers and the homeless, only to have his hopeful altruism continuously disproven by his own theory. He gave up all of his belongings and allowed homeless people to live in his house. Eventually, people began stealing his things until he himself was both homeless and sick with depression.

In the end, he lost everything in his effort to disprove his own theory. George Price committed suicide in January of 1975.

3 Weighing The Soul

In 1901, a doctor by the name of Duncan MacDougall made a discovery that he thought would revolutionize science—a way to measure the mass of the human soul. While it may seem crazy, the loss of mass that was experienced by his patients is documented as real.

MacDougall began by recruiting participants who were in their last few days of dying from tuberculosis. He took his six participants, laid their beds on a large scale, and closely monitored their weight before and immediately following their passing. What he discovered was astonishing: The subjects lost, on average, 21 grams (0.75 oz) in body weight when they died. With no other possible explanation, MacDougall concluded that this must be the exact weight of the human soul.

He claims that the weight drop couldn’t be a result of evaporation, sweat, or loss of bowels because of how rapidly the drop occurred. He also claimed that it could not have been loss of air in the lungs, because when he attempted to force air back into the patients, the scale didn’t change. His colleague and critic, Augustus Clarke, believed the weight change to be caused by the sudden rise in body temperature as the blood stops being cooled and circulated—but Dr. MacDougall maintained his theory, testing it on dogs as well as other animals and finding no weight drop as he did in humans. MacDougall believed that his hypothesis should be put up to more testing due to his small sample size, but his research ended when he abruptly died in 1920.

2 Living Digestion

Scientific discoveries often stem from the sacrifice of others, and the discovery of human digestion is no different. William Beaumont was a surgeon for the United States Army during the 1800s. He came across a man by the name of Alexis St. Martin who had been injured while working for a fur company. St. Martin was shot in the stomach by a buckshot-loaded shotgun, which ripped a large hole right through his skin but let his organs remarkably intact. Despite Beaumont’s belief that St. Martin was going to die from his injuries, he survived—albeit with a gaping hole that gave a clear view into his stomach.

Beaumont knew St. Martin could no longer work at the fur company, so he hired him as a handyman. As Beaumont examined St. Martin’s odd injury, he did as most scientists would and snatched up the opportunity to see human digestion in action. Beaumont ran digestion experiments on St. Martin for years by extracting his stomach juices and even lowering pieces of food into the hole tied on a string. Beaumont was able to discover that stomach acids, and not just the movement of the stomach, play a huge role in the process of digestion.

Understandably, St. Martin grew tired of being Beaumont’s science project and left for Canada. Their paths crossed yet again in 1826 when St. Martin was again ordered to be Beaumont’s handyman. The experiments increased in their intensity as Beaumont put digestion up against the effects of temperature, exercise, and emotion. Beaumont was able to publish a book on his findings, though the two men eventually parted ways for the last time later that year.

1 The Death Diary

Since the beginning of time, humans have been fascinated by death—what it feels like, when it occurs, what we think about as we’re dying—yet to this day many of these questions are still unanswered. On the evening of November 25, 1936, Dr. Edwin Katskee, with the use of cocaine, set out to document this last stage of life by injecting a powerful and lethal dose into himself. He planned to document his thoughts and feelings at each stage on a wall that has come to be known as his death diary.

There had been a note scribbled on the wall stating he did not intend to kill himself, as well as detailed instructions on how to use a pulmotor to revive him, but they were found too late. The rest of his notes are so erratic and illegible that the only way to discern their order is by tracking a visible decrease in legibility over time. Some of the earlier notes included “Eyes mildly dilated. Vision excellent,” “Partial recovery. Smoked cigarette.” But as the drug began to take its toll, Katskee began suffering from seizures and paralysis in waves. High on the wall there was a note that said “Now able to stand up” and another that read “After depression is terrible. Advise all inquisitive M.D.’s to lay off this stuff.”

One of the more difficult-to-read notes reads “Clinical course over about twelve minutes.” Katskee was fascinated by his “staggering gait” and noted that his voice was “apparently ok” despite the fact that no sound came out when he spoke. His final note was only one word, “paralysis” which tapered off into a wavy line down to the floor. An antidote was found with him, but it was never used.

While there is some evidence Dr. Katskee wanted to commit suicide, it is more likely that he meant to document as many stages of death as possible and then ring for help at the last moment, and he tragically underestimated how impaired he would become.

Though many of Dr. Katskee’s scribbles are ultimately illegible and useless, his tragically fatal experiment stands as a testament to the dedication, bravery, and madness of history’s greatest scientific minds.

Shelby is an undergraduate at Arizona State University studying psychology and medicinal biochemistry. She is constantly fascinated by the mysteries of the world around her. She hopes to go on to medical school once she graduates to be able to search for and solve these mysteries.