Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Ways Evolution Made Humans Worse

If engineers could design the most efficient human body, it would likely look considerably different than our actual anatomy. That’s because evolution hasn’t left us with a perfect form but rather a hodgepodge of adaptations. And while these changes in our physical design have admittedly pushed us to the top of the food chain, they aren’t without their drawbacks. Unfortunately, in our journey to the top, we’ve developed aches, pains, and diseases that are new to the primate lineage.

10 Back Pain

There is perhaps no malady collectively griped about more than back trouble. We have upper back pain and lower back pain and hordes of chiropractors promising to realign our vertebrae. So, what gives? Are our spine problems all due to spending too much time hunched over computers and lifting with our backs and not our legs? Well, while those things undoubtedly exacerbate the troubles, scientists say the overall design of our spine is also to blame.

Like modern apes, when our hominid ancestors still moved around on all fours, their spines were shorter, rounder, and didn’t take as much abuse since both the feet and hands were absorbing force, and pressure was more evenly distributed along the spine. However, when we started walking consistently upright, about 4 million years ago, our spines gradually lengthened and became more S-shaped in order to balance our torsos over our hips and feet.

Having a curved spine causes increased stress on certain points of the column, which results in all-too-familiar ailments, such as slipped disks, lumbar pain, scoliosis, kyphosis (hunched back), and more. Furthermore, the way we walk (one foot in front of the other and alternating arms) creates a twisting motion that can eventually cause the discs between the vertebrae to wear down and lead to a herniated disc.

No other primate (aside from our immediate ancestors) suffers from such issues.

9 Doomed For Fatness

In some ways, the evolution of the human body is letting us down because it hasn’t yet caught up to our less active, non-hunter-gatherer lifestyles. For instance, our early ancestors were never sure where their next meal would come from, so the body developed a way to store energy, in the form of fat, for later use. Our bodies became so adept at storing fat that it’s now quite difficult to lose weight and downright impossible to keep off lost weight in the long term. Unfortunately, when there’s a fast food joint on every corner and any time is a good time for a meal, our skill in stockpiling body blubber is now working towards our detriment. Hence, the obesity epidemic and rise in type 2 diabetes.

Although we could avoid the flab if we just exercised more and ate healthier to begin with, if we overindulge and become fat, a change in lifestyle may not be enough to get and keep us thin. According to researchers, when we lose weight, our bodies automatically unleash a cocktail of hormones (including ghrelin, the so-called “hunger hormone”) which change our metabolism and drive us to eat. Also, after losing weight, the emotional part of our brains has a greater response to food, while the part of our brains governing restraint is less active. Essentially, we get a bad case of the munchies and no inner voice telling us to quit stuffing our faces.

If, however, our will power is strong enough and we actually lose weight, our bodies continue their coordinated attacks against “starvation” and do everything possible to make us put the pounds back on. These internal defense mechanisms can continue for years or possibly our entire lives.

Of course, we know it’s possible to lose weight and keep it off, because people have done it. Yet scientists say those folks are exceptions to the rule and to remain thin they must stay hyper-vigilant by forever counting calories, measuring food, exercising hours a day, and constantly watching the scale. Not to mention, people who have lost weight automatically burn fewer calories doing the same activities as compared to people of the same size who never lost weight, which means former fatties have to work twice as hard to stay thin. Most of us just don’t have the endurance to fight the battle of the bulge indefinitely.

8 Anxiety Disorders

Remaining in an adrenaline-filled “fight or flight” stage was beneficial when we were living in nature and regularly trying to outrun animals that would eat us. However, having racing hearts, muscles ready to pounce, and hormones pumping through our bodies isn’t quite so useful when we’re working a desk job. While many of us suppress these unneeded responses, instead of disappearing, they can sometimes manifest as anxiety disorders—at least that’s what some scientists theorize.

According to evolutionary biologist Dr. Stephen Stearns, many of our bodily responses are holdovers from the Pleistocene era from 2 million to 10,000 years ago. Even dangerous or anxiety-causing dreams, such as showing up to work naked or falling off a cliff, may result from our Pleistocene brains telling us the night is an unsafe time.

For some of us, it’s not the stifling of the fight or flight response which leads to anxiety but applying it to every situation (dangerous or not) to the point where we become sick. Psychiatrist Randolph Nesse suggests we sense danger in ordinary situations because the fight or flight response hasn’t caught up to the evolution of our bodies or the world we’ve created. For example, flying through the sky on an airplane or walking into a room full of strangers are things our prehistoric brains would never do—there’s too much inherent risk. Yet today, these things are commonplace. Constantly having to balance societal pressure against our natural instincts is a recipe for unease and stress.

7 Knee Strain

Although the knee is incredibly mobile and excellent at transferring and bearing loads, it is still one of the most commonly injured body parts and accounts for around a million medical procedures per year in the US alone. Again, this is a dilemma other primates don’t have.

It seems by evolving to stand upright, we put much more force on our lower limbs, of which the knees take a brunt of the burden. In fact, when we run, our knees have to absorb forces multiple times our body weight. And, because of our relatively wide pelvis structure (also a result of bipedalism), our thighbones are angled inward toward the knees. This is good for overall balance since it places our feet under our center of gravity, but this awkward angle destabilizes the knee joint itself and makes us susceptible to injury.

Women, who have wider hips than men, have an even greater knee-thigh bone angle and consequently can’t run as fast as men and suffer more knee injuries.

6 Foot Problems

Undoubtedly, podiatrists everywhere are thankful we started walking exclusively on our feet, or they’d be out of a job. It turns out that to gain the ability to do things like stand up and see what’s in the distance or reach tall fruit, we took on plantar fasciitis, bunions, collapsed arches, and other foot difficulties. These foot issues aren’t simply a result of our modern lifestyle or from wearing shoes, as there are fossils of other bipedal hominids who had the same problems.

To accommodate upright walking, our feet became less flexible and developed supportive arches. Still, our feet and ankles aren’t always strong enough to support the amount of pressure we place on them, so disorders are common. Not to mention the fact that the foot has about 26 bones, which came in handy when our feet needed to be flexible and grasp tree branches, but now all those bones just create more potential for things to go wrong.

As paleontologist Will Harcourt-Smith explained, “Because the foot is so specialized in design, it has a very narrow window for working correctly. If it’s a bit too flat or too arched, or if it turns in or out too much, you get a host of complications.”

Dr. Jeremy DeSilva describes the “jury-rigged” evolution of our feet as the biological equivalent of paper clips and duct tape and says even the ostrich foot is better equipped for bipedal walking. However, the ostrich has walked upright for 230 million years, compared to just 5 million for hominids. So, perhaps after another 100 million years or so, we will have fused ankle and leg bones and only two toes.

5 Lost Opposable Big Toe

Not only did bipedal walking give us a host of foot problems, it also caused us to lose a really cool opposable big toe. As much as we like to boast how our opposable thumbs make us superior to other animals, imagine having another grasping “finger” on each foot. If our feet would have remained like those of Ardipithecus ramidus (a human from 4.4 million years ago) then we would still have our opposable toe and the ability to both walk and climb trees. While our gait would look a little wonky as judged by today’s standards, the bright side is we’d never have to bend down to pick something up again, which seems to fit nicely with our tendency for laziness.

That being said, the human body is highly adaptable and some of us, like the African pygmy in the above video, can climb trees (even ridiculously thin trees) with as much ease as a chimp. It simply requires a lot of practice starting from an early age, really strong calf muscles, and training the feet and ankles to be more flexible. In comparison, the average person would shatter his ankle if he were to try and bend his foot to the same angle the pygmies use when climbing.

4 Difficult Child Birth

Yet another trouble caused by transforming a horizontal body plan to an erect one is our extremely difficult child births—at least in contrast to other primates. In female apes the birth canal is oriented in the same position throughout and the baby ape can come out smoothly in one straight shot. On the other hand, the birth canal of female humans shifts 90 degrees at one point, which means women generally need another person to twist and maneuver the baby through the many protrusions of the pelvic cavity. Considering all the twisting and turning and potential for the baby to get stuck, it’s easy to understand why childbirth used to be a leading cause of death in women.

Of course, if humans had stayed on all fours, childbirth wouldn’t be nearly as risky and complicated as it is now, since it was habitual walking on two feet that caused our pelvises to shift and narrow.

3 Shrinking Brains

Contrary to popular belief, the human brain is shrinking and has been for the past 20,000 years. Although it did get larger for the first 2 million years of our evolution, it has since lost a tennis ball–sized chunk of mass.

Admittedly, there’s some debate about whether a shrinking brain is necessarily a bad thing, but there are some scientists who think it’s proof we’re getting dumber. Cognitive scientist David Greary calls it the “idiocracy theory” and hypothesizes our modern society makes it easier for dumb people to survive and procreate, whereas in earlier times, where everyone had to get by on his wits, these people wouldn’t have survived. Consequently, with these dim-witted folks allowed to stay in the gene pool, our brains have progressively gotten smaller. Even though we have improved technology, Greary believes that’s largely a result of societal support and says, in regards to innate smarts, the large-brained Cro-Magnons may have surpassed us.

To be fair, some theorize our brains shrank because they’ve grown more efficient. In other words, to save calories and energy, our brains downsized to keep only the necessary functions and “yield the most intelligence for the least energy.” Others believe our smaller brains are simply a sign of domestication and lower aggression. Followers of this theory cite bonobos and dogs as evidence, since these relatively peaceful animals both have smaller brains as compared to their more violent respective relatives, chimps and wolves.

2 Weaker Bones

Genetically speaking our bones aren’t much different from Homo erectus. Unfortunately, they have about 40 percent less mass, which makes them more prone to breakage and osteoporosis.

So, why are our bones dwindling in density? Apparently, our bodies still have the capacity to develop strong, thick bones, but our lack of movement and pressure starting at an early age has turned us into a bunch of softies. This is why doctors commonly recommend resistance training, since it helps to strengthen bone density. For instance, the arm bones of professional tennis players (who obviously put their arms under regular strain) are nearly as thick as those of Homo erectus.

Women are particularly suffering from bone loss, even in contrast to females from just 30 years ago. While poor diet may have something to do with it, researchers say the bone loss trend started before the agricultural revolution. Thus, lack of physical exercise is likely the main culprit.

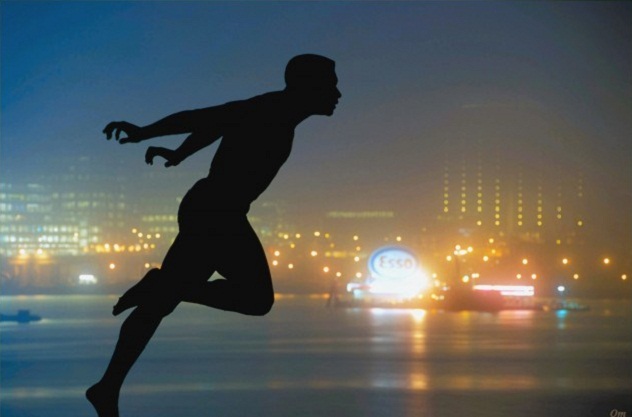

1 Gotten Slower

Considering we’re dumber, weaker, fatter, and plagued with injuries, it should come as no surprise that we’re also much slower than our ancestors. According to research by anthropologist Peter McAllister, the average ancient Australian could run faster than today’s highly trained Olympians. Based on a set of fossilized footprints preserved in a claypan lake, McAllister concluded the ancient Australian who made the tracks could run at least 37 kph (23 mph)—in mud and while barefoot.

In comparison, the current fastest man in the world, Usain Bolt, has reached a max speed of 41.8 kph (26 mph), albeit with considerable training, spiked running shoes, and on an engineered track. If ancient man had such advantages, he’d likely leave Bolt in the dust.

While it seems counterintuitive that we would evolve to be slower, weaker, dumber, and the like, the principle of evolution doesn’t always guarantee progress. Depending on our environment, we can evolve positive or negative traits, and what’s beneficial in one place or time period may not work so well in different circumstances. So, while athletic prowess and survival skills aren’t necessary in our modern, cushy lifestyles, if an asteroid hit the Earth and knocked us back to the Stone Age, then our skills at sitting at a computer for eight hours straight would be utterly useless.

Content and copy writer by day and list writer by night, S. Grant enjoys exploring the bizarre, unusual, and topics that hide in plain sight. Contact S. Grant here.