History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Crazy Facts From Bedlam, History’s Most Notorious Asylum

If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, that path may well cut through the fetid halls of Bethlem Hospital. The institution began as a priory for the New Order of St. Mary of Bethlehem in 1247. As religious folks are wont to do, the monks there began to look after the indigent and mentally ill. The monks believed that harsh treatment, a basic diet, and isolation from society starved the disturbed portion of the psyche.

While their aim was pure, those who would succeed the monks were not so wholesome of purpose. What would follow was more than 500 years of madness and squalor. So awful was Bethlem, that its bastardized nickname “Bedlam” would come to be a universal synonym for lunacy.

10Origins

Bethlem began as a small institution, catering to only a handful of inmates at once. The original structure was built atop a sewer, which frequently overflowed, leaving patients to trudge through the foul muck. It accommodated approximately a dozen patients at any given time, and it featured a kitchen and an exercise yard.

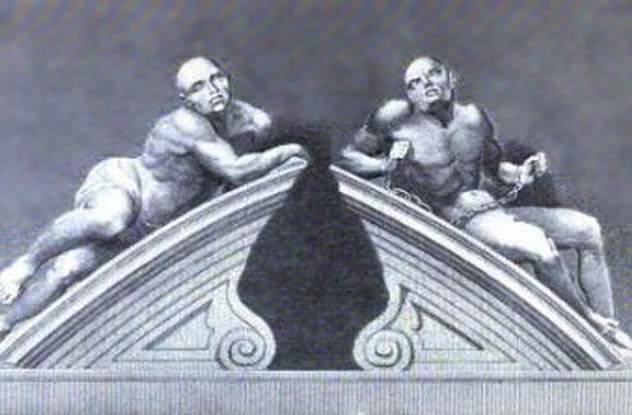

Little is known of Bedlam during the intervening medieval period, but during this time, control of the facility transferred from the church to the crown of England, probably because the government foresaw a potential profit. By the 1600s, the original facility was a crumbling mess. A new building was commissioned in the late 17th century, an imposing structure whose entrance was flanked by two human sculptures wracked with suffering named “Melancholy” and “Raving Madness.” Melancholy appears blank and vacant, where Raving Madness is charged with fury and bound in chains.

Many of the patients locked therein weren’t what we today would consider mentally ill. Along with the raving schizophrenics and psychopaths were epileptics and those with learning disabilities. These souls were often forsaken by their loved ones, allowing for a wild medley of abuse.

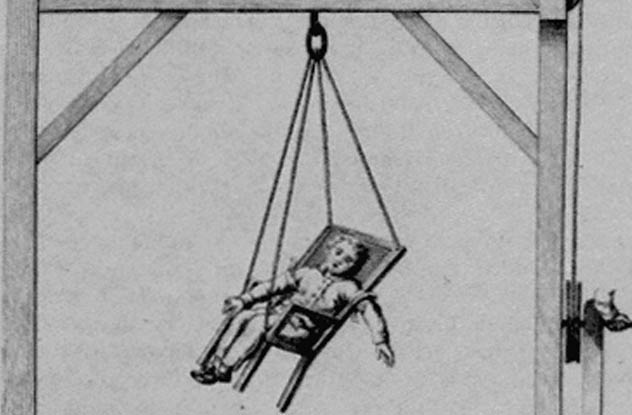

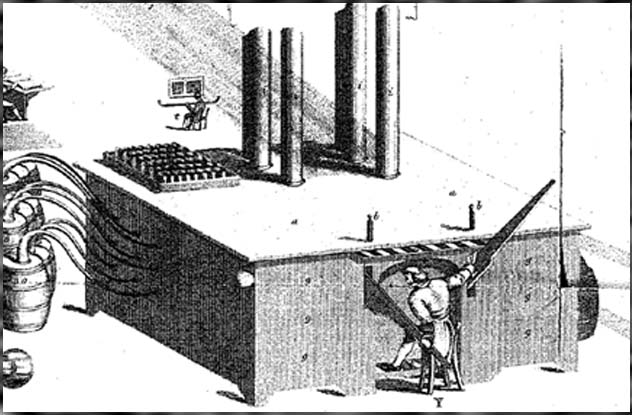

9Rotational Therapy

One of Bedlam’s many controversial treatments, rotational therapy, does not seem particularly awful at first glance. Invented by Erasmus Darwin (grandfather to Charles), this therapy involves sitting a patient in a chair or swing suspended from the ceiling. The chair is then spun by an orderly, the speed and duration dictated by a doctor.

This low-rent carnival ride could rotate a dizzying 100 times a minute. Of course, carnival rides can be great fun, but it is their brevity which makes them manageable. Two minutes in defiance of gravity is a thrill—but can you imagine being stuck on the Zipper or the Scrambler for a few hours?

Countless patients were subjected to this treatment at Bedlam. Inducing vertigo did nothing to curtail the severity of mental illness. The results of rotational therapy included vomiting, pallor, and incontinence. At the time, these were seen as beneficial, especially vomiting, which was considered therapeutic. Oddly enough, rotational therapy would later provide valuable insight to scientists studying the effects of vertigo on balance.

8Famous Patients

While the majority of Bedlam’s patients were sadly anonymous and lost to history, the facility housed a handful of famous inmates. These included architect Augustus Pugin, who designed the interior of the Palace of Westminster (where the parliament meets), a motley crew of would-be royal assassins, and legendary pickpocket Mary Frith (aka Moll Cutpurse).

Perhaps the most larger-than-life patient that ever roamed Bedlam was Daniel, who’d served as a porter for Oliver Cromwell. Daniel was reportedly 229 centimeters (7’6 “) tall, which would have been a shocking sight in the 17th century, when few men topped 6 feet in height. Per Cromwell’s instructions, Daniel was outfitted with his own library.

A religious fanatic and alleged clairvoyant, Daniel had his own “congregation” inside Bedlam, which would gather to hear him preach. Daniel’s ability to see the future supposedly enabled him to predict several terrible events, including a plague and the Great Fire of London in 1666, which destroyed much of the city.

7Art

There’s little doubt that art often walks hand in hand with mental illness; painters like Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Michelangelo all seem to have had demons that sparked their work. So too has Bedlam Hospital done its part to inspire.

Bedlam is depicted as the ultimate ruin of a man named Tom Rakewell in a series of paintings by artist William Hogarth created in the 1730s. The series, titled “Rake’s Progress,” sees Tom inheriting a fortune, which he blows on gambling and prostitutes. In the last of eight paintings, Tom lies prostrate on the floor of Bedlam while society ladies look on and fellow patients suffer through their delusions.

English artist Richard Dadd spent two decades as a patient in Bedlam. Likely a paranoid schizophrenic, Dadd became convinced that his father was the devil, and he stabbed him to death in August 1843. He fled to France to fulfill a lunatic plan to kill the Austrian emperor and the Pope (under the instruction of the Egyptian god Osiris, who he believed communicated with him). He was later captured when he attempted to attack another man with a razor on a train.

Dadd’s masterwork, “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke,” was commissioned by Bedlam head steward George Henry Haydon. The painting, which Dadd spent nine years on before giving it away unfinished, is a window into Dadd’s disturbed mind. It is fantastical, yet filled with baroque details, Shakespearean context, and ties to folklore. It has inspired many over the years, including Freddie Mercury of Queen, who penned a song in honor of the painting.

6Brutal Treatments

Psychiatric treatments have come a long way since Bedlam first opened its doors to the mentally ill. Today, we have reliable pharmaceuticals and established paths of psychotherapy. But in the past, treatments could be decidedly more traumatic.

Bedlam was run by physicians in the Monro family for over 100 years, during the 18th and 19th centuries. During this time, patients were dunked in cold baths, starved, and beaten. William Black’s 1811 “Dissertation on Insanity” described the asylum thusly: “In Bedlam the strait waistcoat when necessary, and occasional purgatives are the principal remdies. Nature, time, regimen, confinement, and seclusion from relations are the principal auxiliaries.” He went on to describe the use of venesection (an archaic term for bloodletting), leeches, cupping glasses, and the administration of blisters.

Bedlam was so horrific that it would routinely refuse admission to patients deemed too frail to handle the course of their therapies. As early as 1758, the conditions and treatments in Bedlam were described as archaic by people like William Battie, M.D., who managed his own asylums.

5Mass Graves

Many patients did not survive their stay in Bedlam. In recent years, excavations for England’s new Crossrail system have uncovered mass graves in London, including those of asylum residents and plague victims. After patients died, their families often abandoned them, and the bodies were hastily disposed of without benefit of a Christian burial. Hundreds of skeletons from Bedlam were discovered on Liverpool Street, at a site which is slated to become a modern ticket hall. Before construction can begin, 20 archaeology digs must be completed to comply with planning regulations.

Many of the remains date back to the 16th century and are being studied at the Museum of London before being reinterred. History describes a burial ground next to the hospital whose keeper was charged to “smother and repress the stenches” from the corpses within. Among the bones, even more ancient finds have been made, including a golden coin nearly 2,000 years old, depicting the Roman Emperor Hadrian.

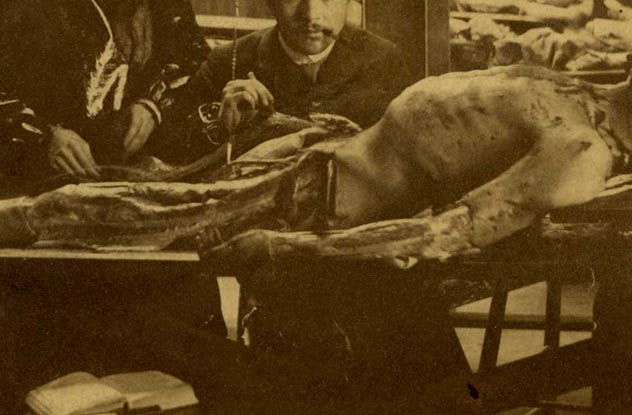

4Dissections

In the 18th and 19th centuries, anatomical studies were in vogue in Europe. Unfortunately, there was a vanishingly small supply of corpses to dissect; only those of indigents and executed criminals could be used for scientific purposes. This led to the grisly cottage industry of “body snatching”—raiding recently filled graves to sell the bodies to medical schools.

In the late 1790s, a man named Bryan Crowther was brought onto the staff of Bedlam as the chief surgeon. Crowther was tasked with attending to sick patients, but he was much more interested in them after they died. As mentioned, families were often uninterested in claiming their deceased relatives, allowing Crowther freedom to carve them up. He was particularly interested in dissecting their brains, searching for some physiological mechanism responsible for mental illness. Although his activities were highly illegal, even blasphemous, he was able to carry on with these experiments for some 20 years.

3Corruption

When control of Bedlam transferred from the church to the crown, a certain amount of corruption was inevitable. The majority of this vice was rooted in embezzlement. Donations of food and other provisions would be taken or otherwise sold by management, leaving patients on starvation rations.

Perhaps the most sinister reign was that of John Haslam, who was appointed to head Bedlam in 1795. Haslam believed that mental illness could be cured but only after breaking the will of the patient. This was accomplished through any number of the aforementioned tortures. Haslam’s ugly tenure came to an end after a visit to the hospital by Quaker philanthropist Edward Wakefield in 1814. Knowing full well what a horror show they had on their hands and fearing bad publicity, Bedlam personnel tried to keep him out, but he eventually gained entry in the company of a hospital governor and a member of the British Parliament.

Wakefield witnessed horrifying conditions. He saw naked, starved men chained to the walls. The worst case was one James Norris, who was clad in a harness with chains running into the wall and into an adjoining room. When the staff saw fit, they would yank on the chains, slamming the unfortunate Norris into the wall. Wakefield inquired how long this had been going on, and Haslam told him between 9 and 12 years. This led to a long public inquiry of the goings-on within Bedlam. Haslam blamed the conditions on his chief surgeon, the butcher Bryan Crowther. Eventually, both men were let go, and Bedlam began taking steps toward more humane treatment of patients.

In 1863, Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum was opened, and it accepted Bedlam’s most infamous and criminal patients, including Richard Dadd. With that, Bedlam’s notoriety dipped considerably, and today, it operates as Bethlem Royal Hospital.

2Political Prisoners

Reasons existed to lock people away at Bedlam besides the treatment of psychiatric issues. Certainly, there were few better ways of silencing an opponent than trapping him in a mental institution. Not only would the person be out of your hair, but the stigma of being a patient at an asylum would undoubtedly damage said enemy’s credibility if he were ever released.

One of the strangest figures in the hospital’s history was a man named James Tilly Matthews. In the wake of the French Revolution, tensions between England and France were mounting, and the possibility of war seemed imminent. Matthews traveled to France, seemingly of his own accord, in an effort to defuse the situation. He was soon locked up by the French on suspicion of being a spy, but after a few years, his claims convinced them that he was merely insane, and he was returned to England. He immediately accused Lord Liverpool, the British Home Secretary, of treason.

Matthews was locked away in Bedlam, where he unspooled a bizarre tale, claiming that he was a secret agent and that his mind was being controlled by the mysterious “Air Loom Gang.” This group used a machine to control his mind by way of a magnet implanted in his brain. Matthews claimed the gang was intent on forcing a war with France. His family believed the dark forces in play were all within Matthews himself, and they had two different doctors go to the hospital to examine him. Both claimed he was quite sane.

None other than the aforementioned John Haslam took a shine to Tilly, using him as the subject for his seminal work Illustrations of Madness. The treatise seemed definitive proof that the man was, in fact, insane and not the unfortunate victim of political scheming. By most accounts, this served as the first fully documented case of paranoid schizophrenia. However, with the exception of his claims about the Air Loom device, Matthews was extremely intelligent and well spoken. Some believe that he merely cracked under the pressure of being used as a pawn in the machinations of two governments.

1Human Zoo

The most notorious aspect of Bedlam was its availability to the public. It was expected that friends and family would drop in on patients, but for many years, Bedlam was run like a zoo, where wealthy patrons could drop a shilling or two to roam the fetid hallways. These visits were so frequent that they made up a significant portion of the hospital’s operating budget.

Wandering through a facility for the mentally ill was not without its attendant risks. While most patients were probably more of a danger to themselves than anyone else, there was also no shortage of psychopaths manacled to the walls. There was also always the chance that some poor, tormented soul might empty his chamber pot over your head.

Henry Mackenzie’s 1771 work The Man of Feeling described a visit to the hospital as follows: “Their conductor led them first to the dismal mansions of those who are in the most horrid state of incurable madness. The clanking of chains, the wildness of their cries, and the imprecations which some of them uttered, formed a scene inexpressibly shocking.”

Mike Devlin is aspiring novelist.