History

History  History

History  Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

Top 10 Weird Facts About Death & Dying In The Middle Ages

Death was experienced very differently in Medieval Europe: people lived in cemeteries, bones were used as decorative objects, and the bleeding of corpses was used as legal evidence in cases of murder.

Here are a few surprising facts from the wondrous world of the Middle Ages.

10Living in Cemeteries

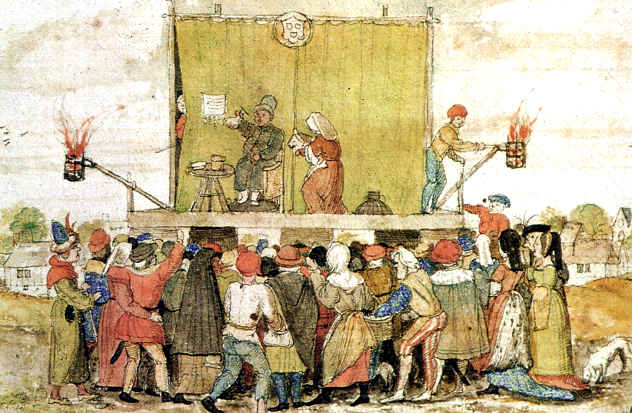

In the Middle Ages, cemeteries were very different places from what we would expect. Rather than being destined exclusively for the disposal of the dead, they were lively places of social activity.[1] All the most important events occurred in cemeteries: local elections, trials, sermons, and theater plays. Prostitutes would also operate within cemetery grounds.

As historian Philippe Aries reports, cemeteries were also places of commerce: belonging to the church, they were exempt from taxation, and became sought-after venues for small business owners.

9Cruentation: Bleeding Corpses as Legal Evidence

Cruentation, the understanding that dead bodies would bleed in the presence of their murderer, was a common belief in the Middle Ages. In King James’s Daemonologie (1597), the fact is described in the following words:

“In a secret murder, if the dead carcass be at any time thereafter handled by the murderer, it will gush out blood as if the blood were crying to heaven for revenge on the assassin.”

Cruentation had legal validity, and it was used as a test to expose murderers from Germanic times until as late as the seventeenth century.[2] This belief was based on the common understanding that dead bodies retained a spark of the life that had abandoned them, and they had, therefore, magical properties.

8Ossuaries

Overcrowding was a common problem in medieval cemeteries. To free up space for new burials, bones and skeletons were exhumed and stacked neatly in ossuaries, also known as “charnel houses.”[3] Many such places acquired a great artistic value, as bones were arranged to produce aesthetically pleasing patterns and ornaments.

In fact, ossuaries were not merely a solution to a practical problem: they conveyed a religious message. Observing the bones was meant to encourage the believers to meditate about their mortal state. The remains were usually displayed next to the inscription “You are what we were—we are what you shall be,” urging visitors to repent and prepare spiritually for their death. Some more recent ossuaries can still be visited to this day.

7Revenants and Their Theological Problems

The idea that the departed may interact with the living was widespread in the Middle Ages, and there are many reports of dead bodies emerging from their graves.[4] In a collection of such anecdotes, gathered by churchman Willian of Newburgh (12th Century, England), it was claimed that “the corpses of the dead [ . . . ] leave their graves and wander around.” And in Melrose Abbey, Scotland, the monks had repeatedly been visited by a dead priest who kept “groaning and murmuring in an alarming fashion.”

Revenants posed a significant theological problem: were such resuscitations divine miracles or demonic acts? The answer depended on the context, although it was generally agreed that, if a dead body were possessed by a demon, the corpse would have returned to a lifeless state after an exorcism.

6The Fear of Sudden Death

While in our time, a swift death is generally considered desirable, this was not the case in the Middle Ages.[5] Sudden deaths were for murderers, suicides, and those who had sinned against God—not for honest and honorable people.

It was believed that dying suddenly would have caused the spirit of the dead to wander eternally in the world of the living. This was mostly because an unexpected death prevented people from spiritually preparing by confessing and taking the last rites.

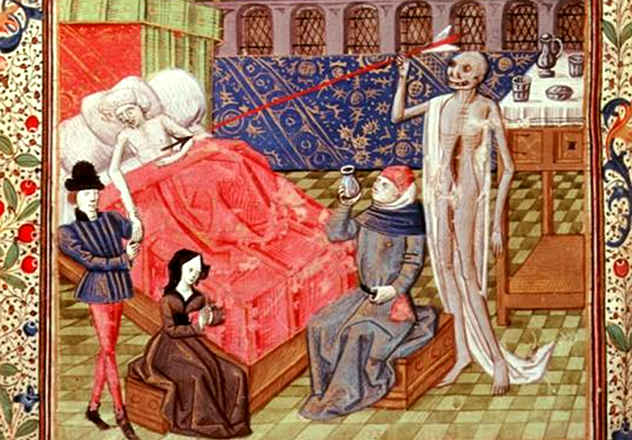

Treatises called Ars Moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) existed to prepare the dying for a “good death.” These often contrasted peaceful scenes of people in prayer and surrounded by their family with images of sinners dying among devils and monstrous creatures.

5Danse Macabre

The “Dance of Death,” often painted in charnel houses in medieval and renaissance cemeteries, portray different members of society being carried away by dancing figures of the dead. The message is clear: regardless of wealth and social status, we are all equal in our unavoidable demise.

Interestingly, despite their grim subject, the Danse Macabre had a strong comic connotation.[6] Nuns are caught in indecent acts with their lovers, and doctors are portrayed observing vials of their own urine, challenged by mocking skeletons to cure their own death if they can.

While the personifications of death are mostly portrayed as mocking or indifferent, there is one curious exception. In the Danse Macabre of La Chaise-Dieu (France, 15th Century), Death is shown covering its face before carrying away a little child, perhaps in an attempt not to scare him.

4Transi Tombs

These tombs display effigies of deceased persons where the dead are represented as being in an advanced state of decomposition, often even devoured by monstrous creatures, toads, or snakes.[7] The word “transi” indicated a body in the process of decomposing: not a skeleton and still recognizably human.

In some cases, the tombs have two levels: on the top, the person is depicted as peacefully departing life, often in prayer. On the lower level, the same individual is shown in an advanced state of decomposition.

The tomb of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany in St Denis (Paris, 16th Century) is particularly descriptive; the artist captured even the smallest details. Beneath the praying figures of the king and queen, the two bodies are shown bearing the marks of the embalmer’s stitches on their stomachs.

3Frau Welt

These bizarre statues, mostly found as decorative elements in German cathedrals, depict beautiful young men or women. While the front of the statue portrays an image of health and happiness, the back reveals rotting flesh, horribly disfigured by maggots, worms, snakes, and toads.

Like many of the aspects described in this list, Frau Welt had an allegorical meaning, as it embodied the deception of the world: beauty, plenty, and the mundane pleasures of life are temporary and superficial, and they lead to a state of moral corruption.[8]

2Apparent Death

In the Middle Ages, the absence of breathing, movement, and sensitivity was generally considered sufficient to diagnose the death of a patient. Yet, there are reports of rather unusual methods being used to ascertain that death had occurred. In La Chanson de Roland, the epic poem, Charlemagne bites Roland’s toe hoping that the pain may awaken him.[9]

Medieval doctor Bernard de Gordon suggests to “call [the person] aloud, pull his hair, twist his fingers [ . . . ] and sting him with a needle.” If all such methods fail, the doctor suggests to put a small ball of wool next to the mouth of the patient: if the threads move, then the patient is still breathing.

Cases of apparent death would not have been frequent, as the dead were often kept in the house for a few days before the funeral.

1The Cult of Relics

The cult of relics is one of the most striking aspects of the Middle Ages. Whole bodies or body parts, thought to have belonged to Christian saints, were believed to have powerful healing properties.

The cult reached its peak between the 11th and 13th century. People would travel great distances to be able to pray before the relics, asking to the saint to intercede for them.

Fragments of relics were even sewn into altar cloths, and it was believed that the Eucharist (Holy Communion) could only be celebrated on an altar covered with such cloth.[10]