Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Inspiring Stories Of True Love From The Holocaust

Few events in human history were as evil and as powerful as the Nazi holocaust, but hiding among the horror were pockets of resistance, resilience, and humanity’s refusal to give in. It’s heartening to know that one of the best things of which we are capable—love—can survive and flourish even under the worst circumstances.

10Jerzy Bielecki And Cyla Cybulska

Cyla Cybulska was shipped to Auschwitz with her parents and siblings in 1943. She was the only member of her family who left the camp alive, and she owed her life entirely to a man named Jerzy Bielecki. Jerzy had been in the camp for three years when Cyla arrived. He was a Roman Catholic, imprisoned for helping the Polish resistance. She was a Jew.

Jerzy was working in a grain silo when he first saw the young woman he’d fall in love with, who had been assigned to repair sacks. Looking back in 2010, he said, “It seemed to me that one of them, a pretty dark-haired one, winked at me.” They stole a few words together when they were able, and they were soon smitten. Jerzy made it his goal to get her out.

He spent eight months stitching together a guard’s uniform using scraps of material one of his friends was able to steal from a warehouse. He stole a pass and forged documents for taking a prisoner to work at a nearby farm. On July 21, 1944, he collected Cyla from her barracks, and they walked out of the gate. They didn’t stop for 10 days, when they reached the home of one of Jerzy’s relatives. He rejoined the Polish resistance and found a hiding place for Cyla using his contacts. He went to fight, with no idea he wouldn’t see Cyla again for almost four decades.

Somehow, each came to believe the other had died. Cyla moved to Brooklyn and married, while Jerzy started a family in Poland. In 1983, Cyla told the story to her cleaner, who found the words familiar, saying, “I saw a man telling the story on Polish television. He’s alive.”

Cyla was able to find his phone number and saw him again a few weeks later. When she arrived at the airport in Krakow, Jerzy gave her 39 roses, one for each year since they’d last been together. They became good friends, and despite living on different continents, they met 15 more times before Cyla died in 2005.

9Manya And Meyer Korenblit

The story of Manya and Meyer Korenblit has been described by their son as one of miracles. They were two Jewish teenagers in love when Nazis began rounding up people in their Polish town of Hrubieszow. At first, they were placed in ghettos, but they were later carted away to a concentration camp. By the end of the war, 98 percent of the town’s Jewish population had been killed by the Nazis.

The lovers went to the same camp, Budzyn. Meyer would sneak to the fence between the men’s and women’s sections to talk to Manya, and it was there they made a promise. Once everything ended, if they both survived, they would return to their hometown to wait for each other. They were separated shortly afterward and spent the next three years in 11 different camps.

When they were liberated, they weighed 64 kilograms (143 lb) combined. That’s less than the average weight of a single European adult today. Meyer had escaped a death march from Dachau concentration camp and hidden on a farm before Americans found him. Manya was the first to make it back to Hrubieszow. She had to wait six weeks, not knowing Meyer’s fate—but he made it home to her.

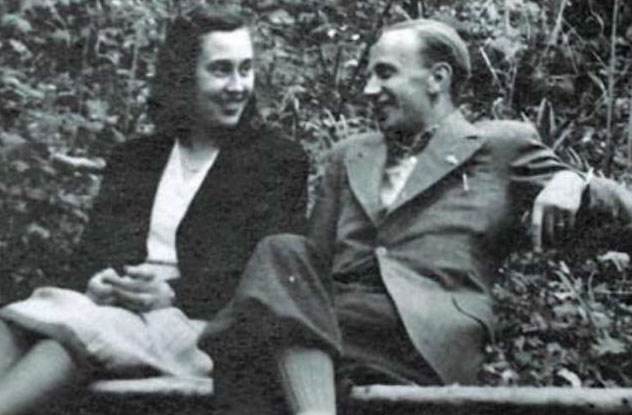

8John Rothschild Saves His Fiance

Swiss Jew John Rothschild met his future wife Renee in 1939. She was German and had been living in France since the Nazis came to power in 1933. She was forced to leave her home in Strasbourg when the city was evacuated by French authorities as preparation for the pending Nazi invasion. Renee knew John’s family, and they invited her to stay at their farm in the French town of Saumur. The two, both 19, fell in love, and they were engaged after three weeks.

Their world fell apart over the next few years. John returned to Switzerland to perform his national service, and Renee found work elsewhere in France. In July 1942, all of John’s family in Saumur were deported to Auschwitz. The following month, Renee was imprisoned at the Drancy internment camp, with Auschwitz as her eventual destination.

John had only one way to save her. He left the safety of Switzerland and became one of the few Jews to go out of his way to get into a Nazi prison camp. He’d brought a gift of cigars for the camp commander, Swiss work papers for Renee, and little else. He remembers it as an unnerving experience, saying, “You can imagine the feeling I had when that gate closed behind me. They could have just kept me there.”

It took two days, but the French camp commander agreed to let Renee go—it would be another year until the Germans took direct control of the camp. John and Renee now just faced the small matter of fleeing Nazi territory. They made their way to a border town and were able to find someone to guide them to a gap in the barbed wire fence along the Swiss-French border. When the disheveled pair told their story to a hotel clerk in Geneva, they were given the best suite for the night. They married the same year and are still together over 70 years later.

7David And Perla Szumiraj

David Szumiraj went to Auschwitz in late 1942. During his time there, he tended potato fields, where he worked near a young woman named Perla. The two weren’t allowed to speak, but when guards weren’t looking they made eye contact.

The shared glances were enough for the two to develop feelings for each other. Once they were able to talk for the first time, David says, “It was already inside us, the idea that we were a couple, that we were going to get married.” Their first conversation ended with their first kiss.

In January 1945, with Soviet forces approaching, the Nazis began moving prisoners. The evacuation of Auschwitz was one of the most notorious death marches in history, killing 15,000 people. After a week of passengers eating nothing but snow, David’s train was attacked by British planes. Weighing just 38 kilograms (83 lb), he survived by eating grass until American soldiers picked him up. Today, he still won’t eat lettuce.

David had no idea where Perla was. He sent a friend to a camp in Hamburg that housed lots of women—and she was there. The first David knew of his friend’s success was when Perla jumped out from behind a tree at the army base where David was staying.

They married, had a daughter, and decided to move to Argentina to be with some of David’s surviving family. They couldn’t afford the $20,000 immigration fees, so they had themselves smuggled into the country from Paraguay instead—and remained happily married for the next six decades.

6Margrit And Henry “Heinz” Baerman

Before Heinz Baerman died in 2013, he and his wife Margrit spent much of their time telling their experiences of the Holocaust to younger generations. They spoke to children in schools and museums about the beatings and starvation they’d experienced at the hands of the Nazis—but also about the shared love that got them through it.

They had met not long before the war, in Cologne. At one point, Heinz had been forced to survive by gnawing on bones dumped in a pile of trash outside the guards’ kitchen in his slave labor camp. When he somehow made his way to the fence of the camp where Margrit was being held, she said “he looked like a skeleton.” She begged the commander to let him in so she could look after him for a few days. To her surprise, he agreed. However, they were soon separated.

When Margrit was liberated in 1945, she had typhus and weighed 30 kilograms (68 lb). She says her love for Heinz gave her the strength to continue. He tracked her down by sending a postcard to “The Oldest of the Jews in Neustadt in Holstein” asking them to find her and ask her to contact him.

The couple emigrated to Chicago after they married and were together 67 years before Heinz was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Three weeks later, he died in his wife’s arms.

5Olga Watkins And Julius Koreny

It was 1943 when 20-year-old Olga Watkins met a Hungarian diplomat named Julius Koreny in her home city of Zagreb, Croatia. Olga later described him as “hardly my type, but our feelings for each other grew.” The two got engaged, but Julius was arrested by the Nazis and imprisoned in Budapest.

Olga had no intention of abandoning her man, so she made the 340-kilometer (211 mi) trip to find him. She was forced to use a false name, and at one point, she herself was locked up for two weeks. But she made it, and she bluffed her way into the prison to speak to Julius. Shortly afterward, he was moved to Dachau, a concentration camp in Germany.

Olga followed, traveling another 700 kilometers (440 miles) only to find that Julius had been moved again, farther into Nazi Germany. She reached the next camp in Ohrdruf around the time that Germany was being liberated by the Allies—so when she found out Julius had been moved a third time, she was able to make the final part of her journey a little more easily. She met up with him in a hospital in Buchenwald. The naturally astonished Julius asked incredulously, “Oh God, how did you find me?”

Though they married, there is a bittersweet ending to their story. Julius was at their home in Budapest in 1948 when Olga traveled back to Zagreb to visit relatives. When the Iron Curtain fell, they were on different sides and were unable to reach each other. They both remarried and didn’t meet again until the 1980s. Their reunion encouraged Olga to write a book about her epic journey through war-torn Europe.

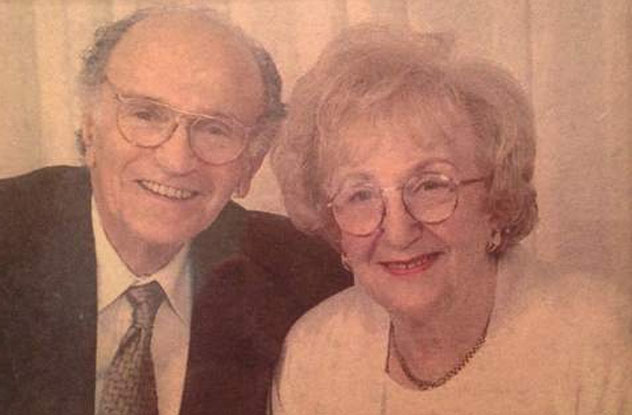

4Howard And Nancy Kleinberg

Bergen-Belsen was hellish even by concentration camp standards. Thousands of corpses were piled high around the camp, and it was overrun with typhus, typhoid, and tuberculosis. A lack of food had forced some captives to resort to cannibalism. When the camp was liberated by the British, there were over 38,000 prisoners, but most were so ill that only 10,000 survived.

Howard Klein seemed almost certain to be among those who died. After being ordered by camp guards to push bodies into a pit, he became exhausted and collapsed among them. “I felt I had to lie down in order to meet my maker,” he said. A young woman named Nancy spotted him among the bodies—and realized he was still alive. Her companions were skeptical he could be saved, but at her insistence, they moved him to a bunk bed.

Howard was too ill to move or speak. Nancy nursed him for a week before he was well enough to talk to her. She looked after him for another two weeks until he disappeared while she was away getting food—the British had moved Howard to a hospital, and Nancy was unable to find him. He’d been so close to death that it took him six months to recover.

By sheer coincidence, both Howard and Nancy separately chose to emigrate to Toronto. When Howard found out that Nancy was living in the city, he turned up at her door unannounced with a bunch of flowers and no idea what to say. “How many times can you say ‘Thank you for saving me?’ ” he recalls. “I was lacking words.”

They married three years later, and as of 2013, they were still going strong. Howard has spent their years together treating his wife “like a princess,” according to Nancy. That sounds like a pretty good way to say thank you.

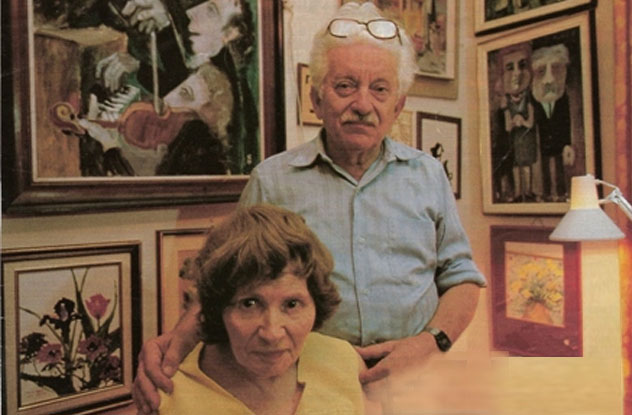

3Joseph And Rebecca Bau

Love was forbidden among the Jews in Nazi concentration camps. However, Joseph Bau and Rebecca Tennenbaum were not people who gave in to the Nazis. Before he was imprisoned, Joseph had used his skill as an artist to create fake documents that saved hundreds of lives. On February 13, 1944, the couple married in the women’s barracks of the Plaszow forced-labor camp. If they’d been caught, everyone present would have been killed.

The couple had crafted their wedding rings from a spoon. Joseph was later freed from the camp by Oskar Schindler, and their wedding was featured in the film Schindler’s List. That list originally contained Rebecca’s name, but she switched Joseph’s in instead, sending herself to Auschwitz and almost certain death. Amazingly, she survived, and the couple reunited after the war.

Today, their wedding is still celebrated as a symbol of hope. Following festivities for what would have been their 70th anniversary in 2014, the couple’s daughter Cilia said, “According to Jewish tradition, in times of deep desperation, a wedding ceremony would be held in the cemetery, symbolically linking the living and the dead.” The Plaszow camp had been built on a cemetery.

2Gerda And Kurt Klein

When Barack Obama presented Gerda Weissmann-Klein with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010, he said, “She has taught the world that it is often in our most hopeless moments that we discover the extent of our strength and the depth of our love.” The strength referred to 60 years working as an author and campaigner for human rights. The love referred to the moment that Gerda Weissmann met Kurt Klein, the man she would go on to spend her life with.

In January 1945, Gerda was one of 4,000 Jewish women marched from slave labor camps by SS guards. They walked for 550 kilometers (350 mi) over the course of months. By May, only 120 were left alive. During the march, Gerda’s best friend had died in her arms. She had already lost her parents and brother, along with 64 other members of her family. With the last survivors too weak to move, the women were abandoned in an old factory. Gerda weighed only 30 kilograms (68 lb).

On May 7, a car approached the factory. Gerda stood in the doorway while two American soldiers got out. Kurt Klein, a Jew who’d fled to the US from Germany before the war, was one of them. “He looked like God to me,” Gerda said. When Kurt asked about the other women, he referred to them as “ladies,” a title Gerda hadn’t heard in over six years.

When Kurt held open the door for her so they could go inside, Gerda said she felt “restoration of humanity, of dignity, of freedom.” They married a year later in Paris, before having two daughters and dedicating their lives to trying to make the world a better place.

1Cyla And Simon Wiesenthal

We’ve mentioned Simon Wiesenthal before. The Austrian Jew survived the Holocaust and later helped hunt down thousands of Nazi war criminals. But the story of his marriage to Cyla Wiesenthal is every bit as spectacular as the story of his fight for justice.

Cyla and Simon married in 1936 and lived in the Polish city of Lvov, which is today part of Ukraine. In 1941, the Nazis arrived, and Lvov became the Jewish ghetto of Lemberg. In October 1941, the Wiesenthals were shipped to a small labor camp, where they worked for a year. By then, the mass killing of Jews was gathering pace, and the couple knew their deportation to an extermination camp was inevitable.

Simon was able to build links with the Polish resistance group Armia Krajowa. He used his job at the camp’s railway shop to obtain charts of railway junctions for the resistance in return for their rescuing his wife. Armia Krajowa smuggled her out of the camp in early 1943 and provided her with a fake Christian identity.

Cyla was sheltered in Lublin, over 200 kilometers (120 mi) to the north. In June 1943, the Gestapo began rounding up suspicious women in the town, so Cyla traveled back to Lemberg to find Simon. After hiding for two days in a train station cloakroom, she made brief contact with him. Once again, he used his resistance contacts, this time to find her shelter in Warsaw.

In 1944, Simon tried to commit suicide. He survived, but the story lost that important detail when Armia Krajowa informed Cyla of Simon’s actions, and she believed he was dead. In the meantime, he was moved to a different camp and met a man who had lived on the same Warsaw street as Cyla. The man told Simon that every building on the road had been destroyed by Nazis using flamethrowers, with no survivors. When Simon’s camp was liberated in May 1945, he contacted the Red Cross, who confirmed his wife was dead.

Except she wasn’t. Cyla had been captured in Warsaw and sent to a camp, and the British had freed her a month before the Americans rescued Simon. Each believed the other was dead, until Cyla was reunited with a mutual acquaintance in Krakow. He was extremely surprised to see her. “I’ve just had a letter from your husband asking me to help locate your body,” the friend explained. Unfortunately, they still had a problem—Simon was in the American zone, and Cyla was in the Soviet.

Simon hired a man named Felix Weissberg to get his wife across the border. However, Weissberg was far from competent. He destroyed Cyla’s papers before getting to Krakow, where he forgot her address. He put a notice on a bulletin board: “Would Cyla Wiesenthal please get in touch with Felix Weissberg who will take her to her husband in Linz.”

When three women presented themselves, all claiming to be Cyla, Weissberg had no idea which one was telling the truth. He couldn’t smuggle three women across the border with new fake documents, so he had to guess after interviewing each one. Luckily, he got it right. The couple reunited, and they wasted no time making up for their two years apart. Their daughter was born nine months later.

Alan found it interesting that after meeting his future wife, Kurt Klein arranged for Oskar Schindler to surrender to the Americans instead of the Soviets.