History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Beloved Saints The Church Just Made Up

The veneration of saints (“cultus” in Latin) has been an integral part of Catholic spirituality. Modern saints such as the recently canonized Popes, John XXIII and John Paul II, have well-documented biographies. But before the Church established a definite canonization process, exceptionally virtuous and heroic Christians were recognized by popular acclaim rather than ecclesiastical decree.

Without critical investigation of an alleged saint’s life, ordinary people depended on legends, myths, romances, and tradition for saintly biographies or “hagiographies.” Such sources are woefully unreliable. Some early Christian hagiographies may have a historical core, but the accretion of legends make it next to impossible to retrieve the real personality behind the tall tales. Others are absolute fiction.

10 St. Veronica

You’ve likely seen this saint’s picture if you’ve ever entered a Catholic church, even if you don’t recognize her name. Churches often include artistic depictions of the Stations of the Cross, which chart Jesus’s passion and death, and the sixth station shows Veronica wiping Jesus’s face.

The piece of cloth she used retained an image of Jesus. Veronica later went to Rome at the request of Emperor Tiberius, whom she healed using the sacred image. Some legends say Veronica stayed at Rome through the time of Paul and Peter’s mission there, bequeathing the sacred relic to Pope Clement I when she died. Others say she traveled to France, where she married and joined in apostolic preaching.

None of these traditions have documentary support. The episode in which she wipes Jesus’s face is not even in the Bible.

The figure of Veronica is probably a product of linguistic misunderstanding. In Rome soon after Jesus’s death, followers did venerate a cloth with an alleged image of Jesus. They called it vera icon (“true image”) to distinguish it from other “face of Jesus” relics. Ordinary people came to mangle the words “vera icon” into “Veronica.” In due course, “Veronica” came to refer, no longer to the cloth, but to the name of the woman who obtained it from Jesus. Popular imagination took off from there.

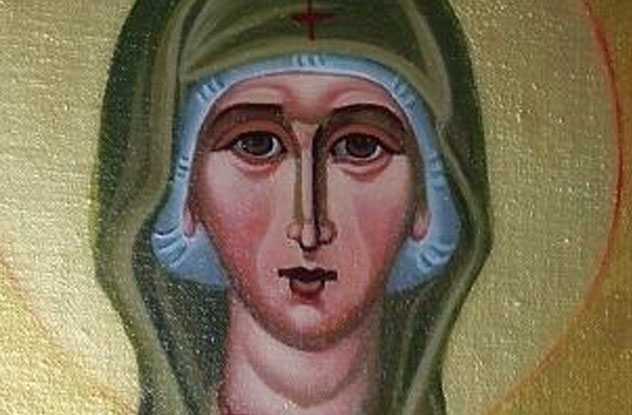

9 St. Euphrosyne

Euphrosyne was the daughter of Paphnutius, a wealthy citizen of Alexandria. Her birth to aged parents answered the prayers of a monk, and Euphrosyne became his student when she grew up. Euphrosyne dedicated herself to a religious vocation, gave away her possessions, and became a nun.

To hide from her family, who’d wanted her to marry a nobleman, she disguised herself as a male monk with the alias “Smargadus.” She entered a monastery near Alexandria as a man, and it was her home for the next 38 years.

Her perfect ascetic life impressed the abbot, and when Paphnutius came to him seeking comfort in his sorrow, the abbot directed him to the care of Smargadus. Paphnutius unknowingly became his daughter’s disciple.

Euphrosyne was soon known for her holiness and wisdom. On her deathbed, in A.D. 470, she finally revealed to her father her true identity. Paphnutius thereafter became a monk himself and lived in his daughter’s cell for the remaining 10 years of his life.

So goes the story of St. Euphrosyne, but she represents a whole class of cross-dressing female saints. The same tale is told of St. Eugenia, for example, a female martyr who disguised herself as a man and became an abbot. Many other saints—Marina, Theodora, Apollinaria, Anastasia Patricia—have purported biographies that resemble Euphrosyne’s.

It seems that medieval folk were fascinated by women successfully impersonating men to elevate their status in the sight of God. Modern scholarship dismisses Euphrosyne’s story as pious fiction and even concludes that St. Euphrosyne never existed.

8 St. Catherine Of Alexandria

St. Catherine is ranked among the most helpful saints in heaven—the “Fourteen Holy Helpers.” She was born into a noble family and studied the sciences. At 18, she confronted the Roman Emperor Maxentius and charged him with cruelty in his persecution of Christians. Maxentius sent scholars to refute her, but she debated them, and her eloquence converted them. The wrathful emperor ordered them executed and had Catherine tortured and thrown into the dungeon.

She nevertheless persisted in her campaign of evangelization, eventually winning over the empress herself. Alarmed, the emperor finally ordered her executed on the wheel. When Catherine touched the device, it was miraculously destroyed. Enraged, Maxentius had her beheaded. Angels carried her body to Mount Sinai, where a church and monastery were later erected in her honor.

Donald Attwater, in his updated version of Lives of the Saints, calls the above legend “the most preposterous of its kind,” as there is “no positive evidence that she ever existed outside the mind of some Greek writer who first composed what he intended to be simply an edifying romance.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, though maintaining belief in Catherine’s historical existence, admits that stories about her “are to be rejected as inventions, pure and simple.”

The 18th-century Benedictine monk Dom Deforis declared the same traditions as false, and since that time, devotion to the virgin-martyr of Alexandria lost all its former popularity. Catherine was removed from the Church’s liturgical calendar in 1969—but she was restored by Pope John Paul II in 2002.

7 St. Margaret Of Antioch

The apochrypal tale of Margaret makes her father a pagan priest in Pisidian Antioch (in modern Turkey). Her mother died when she was a baby, and she was raised by a Christian nurse who adopted her when her father disowned her. Margaret became a Christian herself and consecrated herself to God.

One day, the Roman prefect Olibrius saw Margaret tending sheep and was struck by her beauty. The prefect tried to get her to marry him or become his concubine, but Margaret rejected his advances. Enraged, Olibrius declared her an outlaw Christian and brought her to trial. When she refused to sacrifice to the pagan gods, the authorities tried to burn her, then boil her alive, yet each time, Margaret’s prayers kept her protected.

In one version of the legend, a dragon threatens her in prison, but she makes the creature vanish with the sign of the cross. In another version, Margaret is swallowed by the dragon, but the cross she was carrying irritates the dragon’s innards, and the monster expels her, unharmed. Her persecutors finally put her to death by beheading.

St. Margaret’s life is not documented in history. While her martyrdom is dated to the time of Emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians (A.D. 303–305), there is no certainty even on the century when she supposedly lived. She wasn’t widely venerated until the 9th and 10th centuries.

Margaret’s story sounds suspiciously like the lives of other female martyrs and most likely originated from the same template. The emphasis on the effects of physical torture on female virgin bodies in these legends seem to derive from the notion that women’s bodies were the source of their spiritual weakness; torture could turn their bodies into vehicles of spiritual victory. Margaret’s tale, like other similar legends, provided lurid entertainment to medieval audiences.

6 St. Philomena

No ancient sources attest to St. Philomena. She was entirely an invention of rector Francis Di Lucia and a Dominican Tertiary nun in Mungano, Italy, near Naples.

The pious fiction was inspired by the discovery in 1802 of a tomb in the Catacomb of Priscilla, mistakenly identified as belonging to an early Christian martyr. The name “Filumena” was inscribed on the earthenware slabs closing the grave, so the alleged martyr was assumed to be a virgin called “Philomena.”

The relics were transferred to the church in Mungano, and a nun named Maria Luisa di Gesu began receiving revelations about the life and martyrdom of Philomena, allegedly from Philomena herself. The revelations received the approval of the Holy Office (today’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), and the entire story, as it came to Mother Maria, was written in an official account by Fr. Di Lucia.

Philomena was allegedly the daughter of pagan Greek royalty who had been childless before her birth. Publius, a Christian doctor from Rome, offered to pray for them as he instructed them in the faith. The king and his wife converted, and their prayers were soon answered with the birth of a daughter, whom they named Philomena, or “Daughter of Light.”

When she was 13, Philomena’s father took her to Rome to meet with the emperor Diocletian, who was threatening their state with war. Her story from this point onward runs similarly to St. Margaret’s. Upon seeing Philomena, Diocletian offered to marry her. Philomena refused, as she had already consecrated her virginity to God. Enraged, the emperor threw her into prison and had her scourged. He tried to kill Philomena by throwing her into the Tiber tied to an anchor. When she was miraculously rescued, he tried again by raining arrows upon her. Frustrated yet again, Diocletian finally had her beheaded.

St. Philomena is the only person to be canonized solely based on her miraculous intercessions. Though absolutely no evidence supported Mother Maria’s story, Pope Gregory XVI authorized the saint’s public veneration.

5 St. Barbara

Though St. Barbara was once considered one of the “Fourteen Holy Helpers,” the Catholic Church admitted her non-existence and suppressed her cultus in 1969.

According to legend, Barbara was a beautiful maiden imprisoned in a high tower by her father to keep her from the outside world. While there, she corresponded with the Christian philosopher Origen without her father’s knowledge. She eventually became a Christian herself.

She had three windows put into her bathhouse to symbolize the Holy Trinity. When her father found out, he denounced her to the authorities, but Barbara eluded capture. In time, her father caught her, dragged her home, and after torturing his daughter, beheaded her. He was immediately punished for the deed by being struck by lightning.

As might be expected from legend, there are many versions of this story. But there is no reference to Barbara in authentic historical records of Christian antiquity. Neither does she appear in the original Martyrologium Hieronymianum compendium of martys. The earliest reference in which her name appears is dated to about A.D. 700.

4 St. Alexius Of Rome

According to Greek legend, St. Alexius was the son of distinguished Roman Christian senator Euphemianus. His parents had arranged a marriage for him, but Alexius decided to devote his life to God. His fiancee was supportive and agreed to release him.

On the night of his wedding, Alexius secretly left his father’s house and traveled East to Edessa in Syria. There, he lived as an ascetic and became renowned for his sanctity. A vision of the Virgin Mary proclaimed him a “Man of God.”

After 17 years, Alexius returned to Rome in the guise of a beggar, and for another 17 years dwelt incognito under the stairs of his father’s palace. There, Alexius spent his days in prayer and teaching catechism to small children. It was only after his death around A.D. 417 that a document was found on his body, revealing his true identity.

No trace of the name Alexius can be found in martyrologies or liturgical books in the West before the end of the 10th century. A legend of a certain Syrian “Man of God” composed between 450 and 475 displays similarities to Alexius’s story and may have been its basis. The Greek authors may also be confusing Alexius with St. John Calybata, of whom a similar story is told.

3 St. Eustace

St. Eustace (or Eustachius), whose pagan name was Placidus, was a general in Emperor Trajan’s army. One day, he saw a stag coming toward him with a crucifix between its antlers, accompanied by a voice telling him he was to suffer many things for Christ’s sake. Obedient to the divine summons, Eustace duly converted and was baptized along with his wife and two sons.

Misfortune began to hound him. Denounced for his faith, he lost all his possessions, and his family was taken away by the authorities. The poverty-stricken Eustace sought employment in the fields of a rich landowner. Then he received a summons from the emperor to lead the army against invading barbarians.

In the course of the victorious campaign, Eustace was reunited with his family, but his joy was short-lived. Upon Eustace’s return in triumph to Rome, the new emperor, Hadrian, commanded his general to sacrifice to the pagan gods. Eustace refused. Infuriated, the emperor had Eustace and his family thrown to the lions, but the beasts merely frolicked around them. Finally, Hadrian ordered them roasted alive inside a brazen bull.

The saint was very popular in the Middle Ages and was counted as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. However, the Martyrologium Romanum has dubbed him “completely fabulous,” referring to his story’s authenticity, not his style of dress. The legend of Eustace is a seventh-century production, and his story might have been inspired by a similar tale in the earlier work Clementine Recognitions.

2 St. George

St. George is the patron saint of England and personifies the English ideals of honor, bravery, and gallantry—which is strange because George was not English at all. He was supposedly born in Cappadocia (in modern Turkey) in the third century to Christian parents.

When George’s father died, his mother moved back to her native Palestine, taking George along with her. George joined the Roman army and was promoted to the rank of Tribune. But at the height of the emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians, George resigned from the army.

He tore up the emperor’s edict against the Christians, which infuriated Diocletian. He was imprisoned and tortured by being forced to ingest poison, crushed between two wheels, and boiled in a vessel of molten lead. George miraculously survived all these, his wounds being healed by Christ Himself.

Forced to do pagan sacrifices, George instead prayed to the Christian God. Fire rained down from heaven, and an earthquake toppled the pagan temples, killing its priests. George was finally dragged across the streets of Diospolis (now Lydda, in Palestine) and beheaded. Milk instead of blood flowed from his severed head.

The myth of St. George battling the dragon was a later addition to this story and depends more on the medieval ideals of knighthood than on the earlier biography. Very little is actually known of St. George, and his story should be taken as mythical rather than factual. Even the earliest narrative from the fifth century is, in the assessment of the Catholic Encyclopedia, “full beyond belief of extravagances and of quite incredible marvels.”

Pope Gelasius admitted that George is one of those saints “whose actions are known only to God.” He is so shrouded in legend that some people believe he never existed at all or is just a Christianized version of an older, pagan myth.

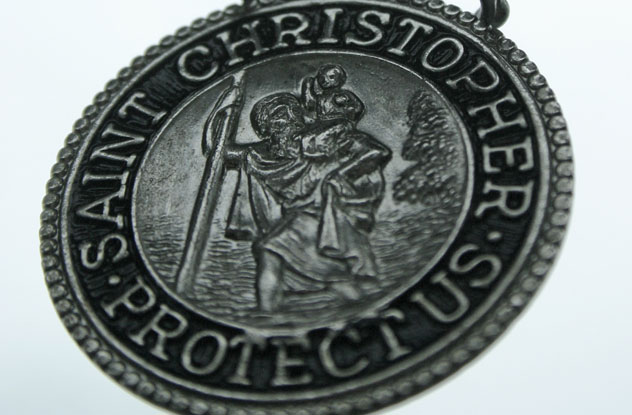

1 St. Christopher

Probably more people have been distressed by the removal of St. Christopher from the Church’s liturgical calendar than any other saint on this list. As patron saint and protector of travelers, St. Christopher is an all-time favorite, his protection invoked even by soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. While the Church has not stripped Christopher of his sainthood, his demotion means his historical status is in grave doubt.

The original Greek legend from the sixth century, which was later embellished, tells of a pagan king whose wife prayed to the Blessed Virgin for a son. Her prayers were answered, and a son was born who was named Offerus. Offerus grew up into a giant of a man. He offered his services only to the strongest and bravest master and wandered the land in search of adventure. A hermit convinced him to make Christ his master, and Offerus decided to dedicate himself to helping people cross a raging stream.

One day, he began to carry a small child across the dangerous torrent and felt the child growing heavier and heavier until the weight nearly crushed him. Upon reaching the opposite bank, the child revealed himself to be Christ. His heaviness was the weight of the world He had borne upon Himself. The child baptized Offerus in the stream, and from then on, he was called “Christopher” or “Christ-bearer.” Christopher was eventually martyred in A.D. 251 after converting many pagans.

This story may have originally been intended as a spiritual parable: Believers carry Christ in their hearts, and the weight denotes the trials of a soul taking on Christ’s yoke. In time, the story began to be understood literally. It has been postulated that the real Christopher is an unidentified Christian martyr from western Egypt. Unable to determine his identity, other members of the church referred to him as “Christopher” or “Bearer of Christ”—an honorific title given to virtuous Christian men. Over time, it became his personal name.

My hobbies are history and chess. My book The Chess Workout is available on Amazon.