Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

10 Forgotten War Leaders Who Saved Entire Nations

History has its pages etched with names that have resounded for centuries—Lord Nelson, whose sacrifice during the Battle of Trafalgar ended the French naval threat; Scipio Africanus, whose masterstroke at Zama vanquished Rome’s greatest enemy; Yi Sun-Sin, whose turtle ships defeated a Japanese armada of more than 300 vessels; and Georgy Zhukov, whose costly-but-necessary measures pushed back the Germans and saved the Soviet Union.

There are those, however, whose names have been forgotten or have faded from memory—even though they led, and in some cases even bled for, their nation or their ideals.

10 Cincinnatus

Rome, 458 B.C.

Lucius Quinctius retired from politics at an old age—he had previously served as a Roman Consul. In 458 B.C., Rome was beset by a threat from nearby tribes. The tribe of the Aequi trapped a Roman army in the mountains; the Aequi and their allies also threatened the city itself.

The Senate, upon hearing of the army’s plight, brought Cincinnatus out of retirement, effectively making him dictator of Rome. Upon reaching the city, he immediately gave orders on how to best deal with the situation, arming the men and leading them on an attack, beating back the unruly tribesmen, and saving the trapped army. The revitalized men rallied, preventing the rival tribes’ incursion into the city. Cincinnatus received a triumphant victory parade to honor his deeds.

Knowing he had accomplished his mission, and despite having everything to gain, he quietly relinquished his position as dictator and went back to his farm.

Cincinnatus’s name is best remembered today as a city in Ohio, named after a society founded by Americans during the revolution. Cincinnati tried to further tie its heritage with Rome by nicknaming itself “The City on Seven Hills,” despite having more than seven.

9 David IV

Georgia, 1121

Following the Seljuk victory against the Byzantine Empire at Manzikert in 1071, the Turks tried to conquer Georgian lands. The Seljuk Empire, stretching from Samarqand in the east to the Greek coast in the west, hungrily eyed the tiny kingdom. Thousands of Turkish civilians and other people within their domain quickly settled in the territory, bringing chaos to the populace. The Seljuk army itself then began a series of incursions into Georgia, taking swaths of land.

In 1089, 16-year-old David, scion of the House of Bagrationi, replaced his recently abdicated father. King David IV started a campaign to retake the lost lands. His decades-long mission to restore the glory of the kingdom culminated in the Battle of Didgori on August 12, 1121. A massively outnumbered Georgian army obliterated the Seljuk Turks. Georgian control of the region was secure, and the kingdom became the most powerful in the Caucasus.

For his preservation and restoration of the kingdom, he was canonized by the Orthodox Church of Georgia. He is widely known in his country as the greatest of its kings, earning the epithet “The Builder.”

8 Tran Hung Dao

Dai Viet, 1283–1287

As commander of the Vietnamese forces, Tran Hung Dao was credited with not one but two victories against massive Mongol invasions ordered by Kublai Khan. The Mongol warlord who controlled China at the time planned to subvert the Dai Viet (modern-day Vietnam) in the south. Tran used guerrilla and scorched-earth tactics until the much larger army was dispirited, demoralized, and diseased. Then Tran counterattacked.

One of his famous exploits was the Battle of Bach Dang River. The Vietnamese drove iron-tipped stakes into the riverbed, and Tran lured in the Mongol fleet of 400 vessels. As the tide ebbed, the Mongol fleet was trapped by the stakes and was easily annihilated by the Vietnamese ambush. While Dai Viet eventually paid off the Mongols to avoid further conflicts, the kingdom was largely able to keep its lands and populace out of the hands of a much larger, terrible foe.

Sources dispute exactly how many Mongol invasions Tran stopped. Nonetheless, he became an enduring symbol for Vietnamese resistance against foreign oppression; streets bear his name in every Vietnamese town, and many streets parallel to a river are named “Bach Dang” in honor of his great victory.

7 Jan Zizka

Bohemia, 1420–1424

Almost a century before Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to a church door, Jan Hus of Bohemia (the modern-day Czech Republic) had become an opponent of the Catholic Church, aggravated by the Western Schism. The Catholic Church, tired of Hus’s antagonism, convicted him of heresy and burned him at the stake in 1417.

His followers rose, and in two years, the Hussites became a thorn in the side of the Church and the Holy Roman Empire. The Pope ordered multiple crusades and invasions against the movement, and they would have succeeded had it not been for Jan Zizka.

Zizka successfully led the Hussites against the crusading armies of Europe in multiple engagements through the use of innovative weaponry—early arquebuses, small cannons, hand culverins, and a wagon fort. Zizka’s tactics were a medieval version of today’s mobile artillery.

The “One-Eyed Zizka” was already blind in one eye due to old age, and he lost sight in his remaining eye after it was struck by an arrow. He fought and won his remaining battles while completely blind.

In 1424, Zizka suffered and died from the plague. Legend has it that he ordered his men to peel off his skin and turn it into a drum which was to be beaten at the head of the Hussite army.

Internal strife led to the collapse of the Hussites a decade after Zizka’s death, but his victories and defense of the movement became one of the first steps towards the Reformation Period.

6 Sultan Kudarat

Mindanao, 1645

By the 1600s, Spain had reached the far corners of the globe. The Philippines, with an Animist and Islamic demographic, was soon converted to Catholicism. Two-thirds of the country was effectively under Spanish rule, and the Sultanate of Lanao in the southern region of Mindanao Island was the strongest bastion of Islam in the nation.

Sultan Kudarat, who ruled these lands, knew from the onset that he had to unite the various tribes in the region, a difficult task due to blood feuds and rival chiefs. He also played a political game, allying with the Dutch against the Spaniards—and vice-versa. This prevented a simultaneous war against two foreign powers, which would have been a death sentence for any technologically inferior nation.

When Spain finally conquered parts of his territory, Kudarat escaped and continued the fight deep in the Mindanao interior. Unable to dislodge the sultan, Spain granted a treaty recognizing his dominion over half of the large island. Kudarat’s defense and rule of the Sultanate allowed Islam to continue to flourish. But Kudarat’s deeds and the preservation of Islam in the region may have also been the cause of tragedy and conflicts that have plagued the Philippines until the present day.

5 Casimir Pulaski

United States, 1777

Polish military officer Casimir Pulaski had a lively career in the service of his country. He and his father joined The Confederation of Bar, which aimed to topple Imperial Russia’s encroachment in Poland. Pulaski fought in numerous engagements, including the Siege of the Jasna Gora monastery, where he protected one of Poland’s holiest icons—The Black Madonna. Pulaski’s exploits were well praised, until he was unjustly accused of regicide.

Now exiled, Pulaski traveled to France when he heard of another nation trying to rise up against imperial tyranny—America.

Under recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, George Washington accepted Pulaski into his service as the commander of his bodyguards. On September 11, 1777, Pulaski reconnoitered and encountered a large British army in Brandywine Creek in Pennsylvania. Pulaski warned Washington, and the Continental Army retreated. The determined Pole then recklessly charged the British lines with his cavalry. The act saved the entire army—and Washington himself—from utter destruction. For this, he was promoted to brigadier general.

Pulaski and his cavalry continued to serve as part of the revolutionary forces until his death in battle two years later. He earned the title “Father of the American Cavalry,” though he received an honorary American citizenship only in 2009. Though there has been a Casimir Pulaski Day every October 11 since 1929, the occasion has largely been ignored—which is a shame for someone who kept the dream of American independence alive.

4 Kamehameha

Kingdom of Hawai’i, 1797

Hawaiian legends told of Kokoika, a bright star foretelling a conqueror who would defeat his rivals and unite the land. When mystic seers saw Haley’s Comet in 1758, it seemed the prophecy was at hand. The worrisome King Alapai ordered his infant son put to death—but he was disobeyed. The child was reared secretly and given the name Kamehameha, which meant “The Very Lonely One” or “The One Set Apart.”

As Kamehameha grew, he consolidated his power, defeating his cousin and other rivals in civil wars using Western arms and preventing an outright takeover by hostile colonial powers. Earning the moniker “The Napoleon of the Pacific,” Kamehameha introduced reforms like the “Law of the Splintered Paddle,” protecting the rights of people such as children, the elderly, and the homeless. The precept is still used even in modern Hawaiian laws.

Though his successors were unable to hold on to the islands’ independence, his cultural and social contributions have lived on. And yet it’s possible that when youth today hear his name, they just think of a cartoon fireball named after him.

3 Admiral William Sidney Smith

Acre, 1799

While Kamehameha may have been called “The Napoleon of the Pacific,” the real Napoleon faced a problem in 1799. The brilliant Bonaparte knew that invading Britain directly would be disastrous for the Grande Armee. He knew that the best course of action was to weaken Britain’s allies and threaten British trade and hegemony in several regions.

His incursion into Egypt caused panic in Britain and its Ottoman allies. Egypt was Ottoman heartland, and beyond was the lifeblood of British economy—India. By March 20, 1799, Napoleon had made his way to the fortress in Acre. Like the Crusaders a century before him, he planned for it to become a secure, impregnable base for future expansion to the east. And he could have succeeded—Britain and multiple nations, as early as 1799, could have been at his mercy—had it not been for William Sidney Smith.

The British admiral boldly captured the French artillery, loaded on nine transport boats. Napoleon, deprived of his precious cannons, ordered multiple assaults on the fortress—all unsuccessful—until disease forced him and his army to retreat. The vital trade route to India was safe.

Years later, a captive Napoleon in Elba reacted “as if his bile stirred” at the mere mention of Sidney Smith. He was heard to have said: “That man made me miss my destiny.”

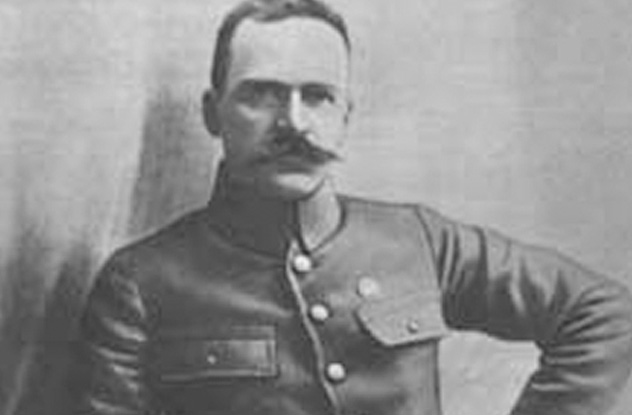

2 Jozef Pilsudski

Poland, 1920

One year after the end of World War I, the Bolsheviks aimed to seize Ukraine and perhaps expand their influence all the way to Western Europe. Jozef Pilsudski, Poland’s chief-of-state and commander of its military forces, allied with the beleaguered nation. The Russo–Polish conflict was a back-and-forth affair. But by 1920, the Soviet armies, inspired by Lenin and Trotsky, pushed westward to Poland.

At the outskirts of Warsaw on August 16, 1920, Pilsudski devised a counterattack against the numerically superior Russians. During this “Miracle at the Vistula,” Bolshevik generals Tukhachevsky, Yegorov, and even Stalin were on the receiving end of a major rout.

The Bolshevik offensive was blunted, and Pilsudski gained honors in his native Poland. With Europe still reeling from the devastation of World War I, who knows how far the Red Army could have marched? Who knows how different the world could have been if this “near miss” had not happened, and Communism engulfed the continent as early as 1920?

1 Marshal Mannerheim

Finland, World War II

Most readers are familiar with the Winter War, the disastrous Soviet invasion of Finland, and with Simo “The White Death” Hayha, the superbly skilled sniper. Finland was, however, involved in three separate conflicts during World War II. Fortunately, Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim was at the helm.

Mannerheim was 72 years old and planned to resign when the Soviets came knocking at the door. But with the man organizing the Finnish defense and boosting confidence, the brave Finns held on for many months during the Winter War (1939–1940) until finally capitulating to the Soviet Union.

When Germany offered assistance, Mannerheim saw an opportunity to strike back at the Communists, but it would put his nation in grave danger. He ordered Finnish soldiers not to advance into Leningrad or even bomb it, despite German demands. This Continuation War (1941–1944) placed Finland in a precarious situation. Teetering too much in support of either side meant alienating the other completely. Britain and other nations that supported Finland before against Russia now decried its attempt to regain its lost lands and even declared war.

As the tide of war turned, Mannerheim knew that Finland would be at the mercy of Stalin—not Hitler and certainly not the Western Allies. One story claims that Mannerheim was able to gauge Hitler’s strength during their meeting (which we still have on tape) by smoking in front of the Fuhrer. Hitler, a non-smoker, could have readily ordered him to stop but did not do so, so Mannerheim knew he had the upper hand.

A separate peace was ensured with the Soviet Union, with Finns fighting to expel their former German allies in the Lapland War.

As the Second World War drew to a close, Red Army tanks rolled down the streets of Budapest and Bucharest. Berlin and Warsaw were reduced to rubble, but Finland still stood independent. Despite an alliance with Nazi Germany, its Jews remained relatively safe from the Holocaust; despite being at war with the Western Allies, it was still held in high esteem as a democracy.

All of that thanks in part to an old soldier, who, like Cincinnatus of Rome, went back to war to lead and serve when his country most needed a savior.

Jo’s wracking his brain trying to see if he omitted any names of great leaders. If you think he forgot your favorite, you can scold him via email at [email protected].