Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Scandalous Saints And Would-Be Miracle Workers

Christian saints and miracle workers are a pretty elite group. They’re the ones who say they’ve been touched by God, given powers of healing, and sent visions in which they claim to see the future or the truth. Occasionally, though, their claims—and their lifestyles—get a little too outrageous, and people start asking some inconvenient questions.

10 Benedetta Carlini

Born in Italy in 1590, Benedetta Carlini, in her defense, probably didn’t have much of a chance at a nonreligious life. With her mother close to dying while giving birth to her, her father prayed for their survival. He promised the baby to God, should they be saved, and they were. Benedetta entered the abbey at Pescia when she was nine years old, and before she was 30, she had risen through the ranks to become abbess.

Her rise through the community was due in no small part to her claims that she had regular visions, usually delivered by various angels and occasionally by Christ. With help from her confessor, she claimed to be fostering these visions, brought by angels who aren’t going to be found in many official religious texts; they had names like Splenditello and Radicello.

Eventually, she went one step further. In 1619, Carlini claimed that she had spoken to a group of saints, the Virgin Mary, and Christ. She had received instructions that Jesus was going to come to marry her. An actual wedding ceremony was set up, complete with gifts, readings, and a gold ring that she claimed Christ had delivered to her.

It was about then that people began to get a little suspicious, realizing that no one else had actually seen anything miraculous happen. Certainly, no one had seen her holy groom at the wedding ceremony, and no one could see the gold ring, either. There were also her lectures, which she gave while possessed by the spirit of Christ, where she told her fellow nuns that absolute obedience was required and that she was absolutely, completely, honest-to-God divine. Her troubles piled up even higher when word got out that she was also carrying on a romantic affair with one of the nuns. Benedetta claimed to be possessed by the spirit of the angel Splenditello while they were carrying on the erotic bit of their relationship.

Not surprisingly, word got out about the supposedly divine marriage, and the grand duke of Tuscany’s papal liaison sent two Capuchin investigators to review the case. Not surprisingly, they found that there was no basis for her claims whatsoever, and they were either rooted in her own imagination or they had been planted there by the Devil.

Either way, she was clearly not right. She was sentenced to be imprisoned in the convent for the rest of her life, which was another 38 years. After she died, her body was protected by the nuns until she could be buried, for fear that believers in the nearby towns would, quite literally, try to get a piece of her should she be canonized after all.

9 Pierre De Rudder

At the turn of the 20th century, Pierre de Rudder was the poster child for the power of Lourdes. When a tree fell on him in 1867, it left him with a broken leg that permanently crippled him. Permanently, that was, until he had been healed by the Virgin Mary. The Belgian laborer had visited a shrine as a last resort, after eight years of suffering from not only the broken leg but an open wound that refused to heal. He didn’t even go to the official shrine. Supposedly, the healing miracle happened at Oostakker, in Belgium, a replica of the grotto in Lourdes. That, the faithful said, was a true display of the powers and miracles that Lourdes was capable of.

The whole thing went 19th-century viral. While believers used his case to support their claims of miracle working, skeptics were going above and beyond to prove that the whole thing was absolutely not true. De Rudder died not long after the claimed miracle, and in 1899, his body was exhumed for examination to see whether or not his bones had been actually mended. Seemingly, they had. The added physician testimony was more evidence in favor of something miraculous truly happening at the replica shrine.

In 1910, the Medical Society of Milan was still discussing the case and tying to figure out just what they could do with it. Both sides were argued; one said that it was a miracle, and the other said that the break in the bones had healed naturally, and the Lourdes shrine had only removed a psychological block that was keeping him from walking again. What was supposed to be a medical conference descended into something of a religion vs. science free-for-all, with the original physicians who examined him being denounced and some even claiming that clearly, there was some other force at work.

It continued to snowball. Suddenly, there were accusations that it was nothing more than a giant Church conspiracy, seemingly supported by the so-called documented evidence, which contradicted itself on which leg was supposedly broken. In 1911, bets were being placed—literally—when a cleric and a philosopher wagered 10,000 francs on the outcome of the case. (It ended undecided.)

There is one theory that stands out as incredibly likely; while he was injured, de Rudder was collecting a pension for his injuries. His patron died, and the money stopped. Needing a way to return to work and save face, he headed to Lourdes and was “miraculously cured.”

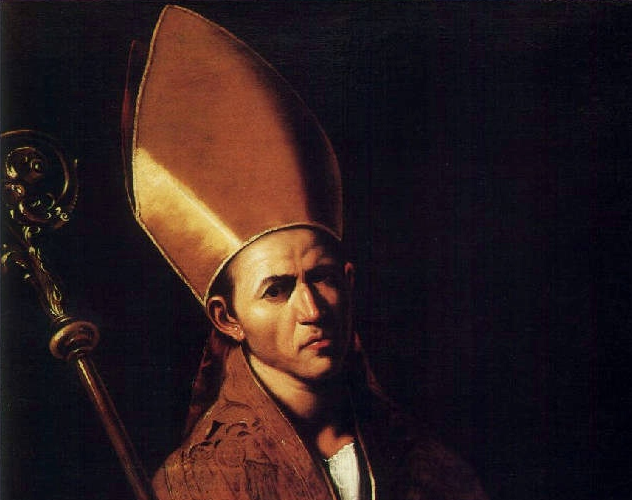

8 St. Francis Xavier

Born in 1506, St. Francis Xavier has been at the center of controversy for centuries. The Spanish-born and French-educated cleric would become one of the founders of the Jesuits, or the Society of Jesus. After a pilgrimage to Jerusalem was thwarted by war, he and his companions went to Rome and accepted a request that they bring Christianity to the Portuguese-run colonies overseas. Xavier headed to India and spent the rest of his life traveling and teaching throughout Asia. His incorruptible body is kept in the Basilica of Born Jesus in Goa, and it still goes on display to the public every 10 years for six weeks at a time.

St. Francis Xavier has been a favorite target of those trying to debunk miracles. The idea is that he’s one of the most well-known for his miracles and proving him a fake would undermine what the whole system is built on. He’s been a target for centuries, starting in earnest in 1752. A book published by the man, who would later become the Anglican Bishop of Salisbury, attempted to draw the line between the miracles of Christian saints and pagan holy men . . . and then promptly said there was no line, because miracles were the stuff of paganism. A big part of the argument hinged on the idea that the saint never spoke of or wrote of his own miracles and that they only started popping up in writing well after his death. Supporters of St. Francis explain it away by saying that he wasn’t about to go around bragging about everything he’d done.

St. Francis Xavier is credited with a pretty impressive list of miracles, including healing, raising the dead, creating and replenishing water supplies, stopping storms, casting out demons and evil spirits, returning sight to the blind, telling prophecies, and other, smaller miracles. He is said to have once lost a crucifix at sea and later recovered it when a crab crawled to him carrying the crucifix.

Canonized in 1623, the saint has been at the center of a massive smear campaign for centuries, one that warranted interference from the Bollandists. The Bollandists are a group of Church scholars responsible for putting together the Acta Sanctorum, a massive collection of official Church texts. The idea was started by a Jesuit in the late 16th century, and now, there are 63 volumes to the work. A part of that work includes arguments in favor of St. Francis and his miracles, and it’s never been officially answered by the saint’s naysayers. However, this might have something to do with it never being really publicized but only published as a part of the Analecta Bollandiana.

His miracles aren’t the only thing to cause scandal, either. In the 1990s, there was a renewed debate over whether or not he was, in the traditional sense, a decent person. Claims include the idea that he hadn’t been too thrilled with being sent off to minister to the people of Asia until he discovered there were “white people” in Japan and China. It’s also claimed that his writings on the people he met in India were less than kind, and he also made it clear that he believed all women were rather shady characters and completely untrustworthy.

7 Padre Pio

Padre Pio was canonized in 2002, and in 2008, his body was exhumed and displayed in a church crypt in Italy. It only reignited the controversy over just what Padre Pio was capable of.

Born in 1887, he was known to speak to—and with—the Virgin Mary and Jesus from a very, very young age. He joined the Order of Friars Minor in 1903, and by 1910, he was showing the wounds associated with stigmata. Even as he gained a huge following of faithful believers (and, incidentally, brought a decent amount of money into his order), there were accusations of fraud. Some of the accusations came from the local clergy, and as more and more miracles were attributed to him, the opposition got bigger and bigger. His “odor of sanctity” was nothing more than his cologne, his psychic abilities could be duplicated by any skilled fortune teller, and his healing abilities were coincidental at best and completely fraudulent at worst, and so on.

The stigmata, however, got the most attention. Attempts were made by various physicians to examine the wounds, but examinations always failed because of the pain that Pio claimed to be enduring. There were some things that just didn’t seem right. The wound in his side was actually on the wrong side and in the shape of a cross rather than a traditional lance. There were no forehead wounds, and those who did get a decent look at the wounds on his hands claimed that they were fairly superficial. And, they were, of course, on his hands instead of his wrists, which he explained away by stating it would be “too much” to appear in the same way as Christ.

According to documents recently unearthed from Vatican archives, the charges of fraud were absolutely true, and at least two Popes went on record saying they thought as much. The documents also include testimony from a pharmacist who claimed Pio had come to him (through the pharmacist’s cousin) requesting a bottle of carbolic acid, which he claimed he needed for sterilizing purposes. The pharmacist was skeptical based on the rather secretive method he went about procuring the acid.

There are still those who remain faithful to Pio. His canonization by Pope John Paul II is linked to the infallibility of the papal office, so he’s a saint. That’s all in spite of a rather grisly discovery: His body was far from incorrupt when exhumed; a wax mask was made for his display, and there were no signs of the stigmata.

6 Simon Of Trent

In 1475, a Franciscan friar named Bernadino da Feltre made a very, very unfortunate and ultimately deadly choice for his Holy Thursday sermon. After an incredibly impassioned and anti-Semitic sermon, the body of a two-year-old Christian boy named Simon was discovered in the Jewish area of Trent on March 26. The Bishop of Trent accused the Jews of murder, leading to mass arrests, torture, and the execution of six people.

The sermon had predicted that there would be a ritual murder in the community in recognition of the Jewish Passover. The body of the little boy seemed to bear all the signs of a ritual killing, and it wasn’t helped by the testimony of a recently baptized man named Johann. Serving a prison sentence for theft, he took advantage of the offer of a shorter sentence to confess that Christian blood was an important part of Jewish Passover rituals. The fallout over the little boy’s murder was so bloody that in April, the region’s nobility stepped in and ended the torture and inquisition. It absolutely wasn’t forgotten, though, and in June, after the confession-by-torture of an 80-year-old man, eight of the town’s Jewish citizens were either burned at the stake or beheaded.

Within a few days of the discovery of Simon’s body, there were already miracles associated with him. Those that came to see the body of the boy who was supposedly martyred for his faith claimed no less than 130 miracles in the year after his death, and suddenly his image was featured in woodcuts and frescoes, the image of innocence and the savagery of the Jews. One painting of him in a Carmelite Church was said to weep and also cause a woman to give birth to twins three months apart.

The so-called cult of Simon added fuel to a fire that was already burning pretty heartily. Pope Sixtus IV eventually ordered an investigation into the miracles and the accusations in hope of restoring the peace. The envoy declared that there were no miracles taking place and there had been no martyrdom. An angry mob forced the papal envoy to seek protection, but with the help of the Bishop of Ventimiglia, arrested the man they found to be the real murderer—a Christian named Enzelin. Even though the announcement that the Jews had been found innocent was made before the executions at Trent, retribution was in full force.

The little boy’s body was kept on public display until at least 1517. In the meantime, Simon has had something of a controversial appointment as a saint, supposedly canonized by Gregory XIII about 100 years after his death. Vatican II disagreed, though, removing him from the Calendar of Saints in 1965.

5 Audrey Santo

Questions of miracles aside, the story of Audrey Santo is an incredibly tragic one. In 1987, the three-year-old girl was playing outside when she fell into the pool. According to her family, she made a full recovery, but she was over-medicated at the hospital and lapsed into a coma. After a three-week coma and a complete failure to respond to physical therapy, she was left unable to speak or move.

Her family took her home to care for her, hoping for a recovery, but something more miraculous happened. When friends and family came to pray for her, blood and oil began to run from the religious imagery she was surrounded with, and her family claimed that she was able to heal others. They drew parallels between her life and historical events. For example, the first medical log from her near-drowning was dated exactly 42 years to the minute from the Nagaski bombing.

By the time Audrey was a teenager, the Massachusetts girl was at the center of constant pilgrimages, based on the idea that she had become a “victim soul,” or someone who suffers so others don’t have to. It’s absolutely not a Church-sanctioned idea, but it was still a popular one throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Those that believe in her abilities claim that she’s been responsible for allowing accident victims to walk again and even curing cancer. There’s also a claim from parents of a missing college student who asked her to help them find him. His body was found in a nearby reservoir not long after they visited her.

Audrey died in 2007, at 23 years old. In 2008, the local bishop gave his approval to an organization formed in her name, allowing them to petition the Vatican for her canonization. It’s not without considerable controversy, though, especially when one of the miracles, the weeping, bleeding statues, has no precedent for being authenticated. Samples of the oil taken from Audrey’s room were tested. They were a combination of chicken fat and vegetable oil. The representatives from the local clergy aren’t saying anything one way or another, and the push moves on.

4 St. Guinefort

In the 13th century, Dominican friar Stephen of Bourbon recorded an absolutely heartbreaking story. It was the story of St. Guinefort, whose selfless actions and martyrdom would begin a cult that would last into the 1930s. It was a cult that the Church fought against, mainly because Guinefort was a dog.

The story says that Guinefort was originally the dog of St. Roch, who had dedicated his life to caring for those who were suffering from the plague. When he caught it himself, he and Guinefort retreated to the woods, where Guinefort brought him food. When St. Roch died, Guinefort was taken in by a local noble family.

The family had a baby. They left the child alone one day, and when they returned, the baby was nowhere to be seen and blood was smeared across the blankets. Thinking Guinefort had killed the baby, the father killed the dog. Only afterward did he see the sleeping baby and the snake that Guinefort had killed. Overcome with grief, he buried the faithful dog.

Once the story got out, Guinefort’s fame grew. Parents started visiting the dog’s grave, leaving offerings and performing rituals around the trees that the nobleman had planted. Stories began of children that had been healed at the grave site, and Guinefort was identified as St. Guinefort and made the patron saint and protector of children. According to Stephen’s writings, the rituals that surrounded the veneration of the dog had every reason to alarm the Church. There was said to be a practice in which a sick child was left on the dog’s grave overnight, lying on straw and surrounded by candles. Many children didn’t survive the night, burned by the candles or killed by predators. If they did survive, though, they were said to be cured of whatever had ailed them.

The Church attempted to put down the cult, digging up the body of the poor dog and destroying the shrine that had been built in his honor. Laws were passed against the veneration of St. Guinefort, but the cult wasn’t about to give up on their sainted canine that easily. St. Guinefort’s wood was still the site of pilgrimages, and the cult was still active through World War I and likely into the 1930s.

The story of St. Guinefort is likely a retelling of an earlier, older story: Brahmin and the Mongoose. By the time the story made it to Europe, the mongoose had become a greyhound, the dog associated with everything noble. Stephen attempted to convince the peasantry that their actions weren’t just deadly, but also devilish, but offerings and visits to the wood were Guinefort was buried continued.

It’s also thought that Guinefort was partially born from another St. Guinefort, who was human. The human saint was also known as a protector of children, and St. Roch, the man whom Guinefort loyally fed, was the patron saint of good dogs. Either way, it’s pretty epic that the cult continued in the face of opposition from the Church.

3 St. Januarius

St. Januarius (or St. Gennaro), is the source of one of the longest-running and most regularly repeated miracles of the Catholic Church. Twice a year, on his feast day of September 19 and on the first Saturday in May, the dried blood of the saint turns to liquid. It’s been happening for more than 600 years, and on the rare occasions that it hasn’t happened, horrible, horrible things were said to come right on the heels of the failed liquefaction. There have been plagues and earthquakes associated with it. On at least one occasion, it’s been rumored to liquefy as a sign of approval. When Pope Francis visited the relic, it liquified in his hands, which the attending cardinals took as a sign of the saint’s approval.

That was in 2015, but there’s been a scientific explanation for the phenomenon since 1992. According to the story, the vials of blood came from a rather bizarre source. The story of Januarius ends in the beginning of the fourth century with his beheading by the governor of Campania, after wild animals refused to attack them in an amphitheater. After his death, his bones were moved several times, and Charles II of Anjou even had a reliquary built for his head. It wasn’t until 1389 that the first mention of the blood is made, and it was only as a diary entry by an Italian writer whom we don’t even have a name for. The legend of the blood coming from the moment of his beheading also doesn’t show up until about 1,000 years after it actually happened.

The blood liquifies when it’s removed from its glass case, and how long it stays liquified varies. Sometimes it solidifies overnight, and sometimes it remains a liquid for days. A number of experiments have some to the conclusion that iron hydroxide, prepared correctly and with a little bit of salt added, will behave exactly like the blood does.

Discovery of such a concoction at about the time that the relic was first mentioned would certainly have been in the realm of alchemy rather than excepted science. Researchers guess—although there’s no proof whatsoever—that the 1317 papal outlawing of alchemy may have encouraged some ingenious practitioners to present their work in a way that wasn’t going to get them excommunicated.

2 Santuario De Chimayo

This one’s a little bit different, as it’s an inanimate object that’s supposed to have healing powers, and the priest who oversees it is sick and tired of telling people that the miracle isn’t in the dirt.

Santuario de Chimayo is in New Mexico, and it’s occasionally called the Lourdes of America. The whole thing started with a legend set in 1810. According to the story, Don Bernardo Abeyta, a member of the Penitentes, was praying in the hills of New Mexico. He saw a strange light coming from the middle of nowhere and, when he investigated, he found a 1.5-meter-tall (5 ft) wooden cross buried in the ground. He dug it up and returned it to his church, only to find that in the morning, it had returned to its original spot. After the cross returned several more times, they took it as a sign that a church needed to be there. So, they built the chapel that’s now Santuario de Chimayo.

It became famous, with around 300,000 people visiting every year. The faithful believe that the dirt from the floor inside the chapel has healing powers, some walking hundreds of miles for the chance to rub the dirt on the parts of their bodies that ails them. Many even take some of the dirt with them.

The chapel is overseen by Father Casimiro Roca, who took over the chapel after it had been all but abandoned by its previous tenants. He’s the one that made it into such a popular attraction, and he’s not at all dishonest about the miracle dirt.

Sometimes, in fact, he seems vaguely annoyed that he has to keep buying dirt to keep the crucifix hole freshly filled. When Roca took over the building, he cleaned it up, added a gift shop, and made no secret of what goes on at the site. People come from all over, some walking for miles carrying crosses, in hopes of being cured by the dirt that Roca and his staff originally gathered from the nearby hills to replenish the dirt that tourists took. Now, they also buy clean dirt and keep it in a nearby dirt storage house. That hasn’t stopped the rumors that the dirt magically reappears due to divine intervention, though, and Roca says that people just might be missing the point. It’s not the dirt that’s miraculous, he says, the miracles are God’s.

1 The Nuns Of Sant’Ambrogio

In 1998, author and historian Hubert Wolf picked up the story of the nuns of Sant’Ambrogio. The story had been long forgotten, buried in the Vatican archives since the 1850s. It was a series of pretty radical accusations brought against one nun by a recently cloistered sister.

Katharina von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen entered the convent of Sant’Ambrogio after being widowed for a second time. It wasn’t long after she entered the convent, though, that she sent a panicked letter to her cousin, who was a bishop in the Vatican. She claimed that one of the sisters there was trying to kill her and that she was only one target of a whole series of scandals, which she related to him after he came and retrieved her, moving her to safety. The accusations and the trial were an absolutely scandalous affair that the Vatican successfully buried for decades.

According to Katharina, the problems centered around the charismatic novice Maria Luisa. Supposedly, Maria Luisa received visions and messages from the Virgin Mary and Jesus and commanded a bizarre sort of respect and obedience from her fellow nuns. She also spent an inordinate amount of time with a man they knew as “the Americano,” which was doubly odd since the nuns weren’t supposed to have any kind of contact with the outside world.

In addition to the visions she claimed to be receiving, Maria Luisa also claimed various other miracles, like the odor of sanctity that she claimed came from her naturally. Katharina voiced concerns about the whole thing, and it was then that she started to find her food was tasting a bit funny.

When Church officials investigated, they found the bizarre veneration went back to the novice before Maria Luisa—Maria Agnese Firrao. There were other stories about her: that she, too, had shown signs of approaching sainthood. In spite of the Church’s earlier ruling that it absolutely wasn’t the case (she was removed from the convent and imprisoned in another), Maria Luisa claimed to be following in her predecessor’s footsteps on her heretical journey to sainthood.

Further investigations found that Maria Luisa would claim to “purify” other nuns by calling on the spirit of Elijah, and saying that by “laying herself over another nun” she would impart some of her own virtue to the less virtuous. She even went as far as having letters written (the author sworn to secrecy), which she could claim were written by the Virgin Mary. While on trial before the Church officials, Maria Luisa swore that she was carrying on her duties as she truly believed she had been tasked by God, continuing the work of her predecessor.

Maria Luisa’s charm didn’t allow her to talk herself out of trouble. After a series of behind-closed-doors investigations, she was imprisoned. Katharina had a happier ending, founding the Benedictine Abbey of Beuron.