Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Fascinating Last Witnesses To Historic Events

Famous historic events can seem fairly remote in modern times, so it’s easy to forget that history was watched and experienced by real people. And the last men and women to pay witness to some of history’s greatest moments have some truly amazing stories of their own.

10The Last Mutineer On The Bounty

The famous Mutiny on the Bounty has been immortalized in movies and books, but few know what happened to the mutineers after they set Captain William Bligh and 18 loyal crew members adrift in a small boat. Led by Fletcher Christian, the mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where they worked as mercenaries for a friendly chief. But they knew the British authorities would eventually come looking for them and Christian began to search for a safe hiding place. Among Bligh’s books, he found a reference to the uninhabited Pitcairn Islands. Although Fletcher didn’t know it, the islands were the perfect refuge, since inaccurate maps made it almost impossible for European ships to find them.

In 1790, nine Bounty mutineers arrived on the Pitcairns, along with six Polynesian men and 12 women. They had left Tahiti just in time to avoid a British ship sent to arrest them. But while the mutineers might have been safe from the British, they weren’t safe from each other. The Polynesian men resented the Europeans, particularly William McCoy and Matthew Quintal, who treated them like slaves and monopolized the women. In 1793, they revolted and massacred five Europeans, including Fletcher, who was shot dead in his garden at the age of 29.

McCoy and Quintal escaped and retreated to the hills, creating a tense standoff. They were soon joined by a rogue Polynesian but later murdered him as part of a truce arrangement. The other surviving mutineers, Ned Young and John Adams, were on better terms with the Polynesians and were allowed to remain with them. That turned out to be a mistake, since Ned Young was eventually able to make a deal with the women and slaughtered the surviving Polynesian men in their sleep. Meanwhile, McCoy had discovered how to ferment alcohol from a local root and soon drunkenly committed suicide by walking off a cliff.

That left just three mutineers—and they had an axe to grind with each other. Ned Young and John Adams both felt their lives were at stake after receiving death threats from Quintal. Taking him by surprise, they executed him with an axe in 1799. A year later, Young died of illness, leaving only Adams. The last Bounty mutineer eventually had a religious awakening, forming a pious Christian community from the women and children on the islands. He died peacefully in 1829, after several visits from British ships who had long lost interest in seeking his execution.

9The Last Person To See Lincoln’s Face

In 1901, 13-year-old Fleetwood Lindley had an interesting excuse to be out of school. His father had sent a message asking his teacher to dismiss him early so that he could go to Oak Ridge Cemetery and take a look at Lincoln’s corpse.

After his assassination in 1865, Lincoln’s body was moved no fewer than 17 times. In 1876, a gang of Chicago counterfeiters even tried to steal it and use it as leverage to get one of their colleagues out of prison. Eventually, Lincoln’s exasperated son Robert decided to deal with the body once and for all. In 1901, he ordered that his father’s corpse be reburied inside a huge steel cage encased in several feet of concrete.

Lindley’s father had actually met Lincoln and eventually came to act as an informal custodian of his tomb. So when he heard that the body was to be buried for the final time, he sent word for his son to bicycle over as quickly as he could. Lindley didn’t know what was going on until he arrived at the cemetery to find workers chiseling a window into the lead casket. Apparently, the body was intact and immediately recognizable, although Lincoln’s “face was chalky white [and] his clothes were mildewed.” Lindley died in 1963, making him the last person to have seen Lincoln’s face.

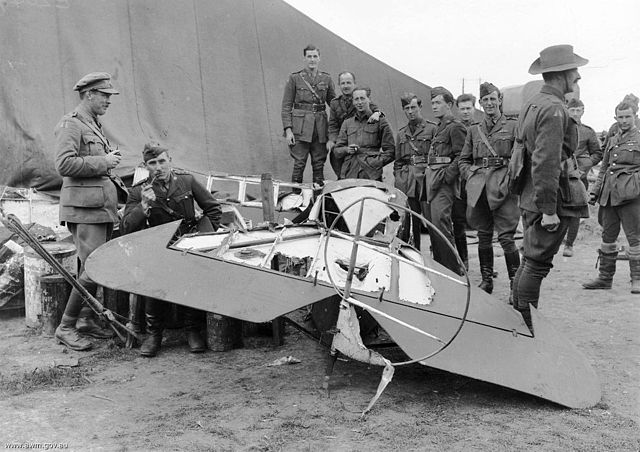

8The Last Witness To The Red Baron’s Death

Even without his connection to the famous Red Baron, Australian Edward “Ted” Smout led an incredible life. When he passed away in 2004, he was one of just six surviving Australian veterans of World War I—and the oldest of the six to boot. Almost 90 years earlier, in 1915, he had lied about his age to join the Australian Army Medical Corps at just 17. He survived the grinding battles of the Western Front, including a nightmarish experience at Passchendaele, where he was buried in bricks by an explosion. He suffered from a nervous condition for years afterward. In 1998, he was honored by the Brisbane government, but still ducked for cover at the first shot of an artillery salute.

Before he died, the 106-year-old Smout officially became the last man to see Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron, shot down. The Baron was leading his famous Flying Circus in an aerial dogfight when his plane was badly hit, probably by Australian machine gun fire from the ground. As a medic, Smout was one of the first on the scene, reporting that the dying Baron’s last word was “kaputt” (“finished”). According to Smout: “I admired his fine leather knee boots, but resisted the temptation to souvenir them, or the Iron Cross he was wearing on a chain around his neck.” However, he did cut off a piece of the cockpit as a memento.

Among Smout’s other cherished memories was Armistice Day, which he spent partying at Paris’s famed Folies Bergere. He was fined 14 days pay for leaving his unit, but luckily he had just been appointed unit paymaster and quietly decided against withholding his own wages. After the war, he became an accountant and was honored for his tireless charity work in 1974.

7The Last Civil War Widow (Died In 2008)

When the 18-year-old Gertrude Janeway got married, the year was 1927 and the US Civil War had been over for 62 years. Her new husband was an 81-year-old Union Army veteran named John Janeway. To make the match even stranger, the couple had waited three years to get hitched, since Gertrude’s mother refused to sign the papers required for a 15-year-old to marry. Although Gertrude continued to receive a $70 monthly war widow’s pension until she died in 2003, she insisted there was no financial angle to the match, calling her octogenarian husband “the love of her life.” The couple built a crude three-bedroom log cabin in Tennessee, where John died in 1937. Gertrude continued to live in the cabin until her own death, almost 150 years after the Civil War ended.

Astonishingly, Gertrude wasn’t even the last Civil War widow (although she was the last Union widow). In 2004, Confederate widow Alberta Martin passed away at the age of 97, having married an 81-year-old veteran in 1927, just a few months after the Janeways’ wedding. Unlike Gertrude, Alberta didn’t claim to have married for love, explaining that “I had this little boy and I needed some help to raise him.” The marriage doesn’t seem to have been especially happy, with Alberta recalling that her husband always grew jealous when she spoke to younger men.

When Alberta died, the press confidently announced the passing of the last Civil War widow—only to be swiftly corrected by Maudie Hopkins, who had married an 86-year-old Confederate veteran in 1936 after he offered to leave her his small farm and pension. Out of embarrassment, Maudie didn’t talk about the marriage for years, explaining that she “did what I had to, what I could, to survive. I didn’t want to talk about it for a while because I didn’t want people to gossip about it. I didn’t want people to make it out to be worse than it was.” Maudie passed away in 2008, almost certainly the last Civil War widow.

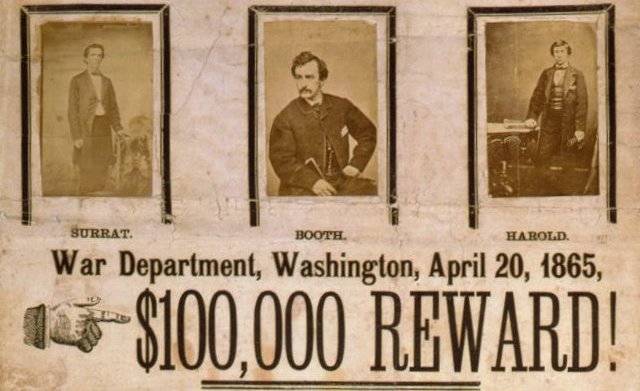

6The Last Lincoln Assassination Conspirator

As the nation wept for the death of Lincoln, most of the conspirators were swiftly brought to justice. All except for one: John Surratt Jr. Introduced to John Wilkes Booth in 1864, Surratt soon joined his group of conspirators. But it’s never been clear just how much involvement in the assassination he had. Surratt himself admitted that he had been part of a failed plan to kidnap Lincoln in 1865, but insisted he wasn’t aware that Booth had gone on to plot a murder. On the night that Booth killed Lincoln and the other conspirators tried to kill the Secretary of State and Vice President, Surratt’s whereabouts are uncertain and remain the subject of much speculation. Surratt claimed he was in Elmira, New York, but others have suggested he was in Washington.

Either way, Surratt quickly fled the country disguised as an English tourist, employing skills he had learned delivering messages for Confederate spies. After arriving in Montreal with detectives on his trail, Confederate sympathizers hid him until he could make his escape to England. He later moved to Italy, where he became a soldier in the Papal Zouaves until an old acquaintance spotted him and alerted the American vice-consul in Rome. Always resourceful, Surratt slipped away again but was captured in Egypt and extradited to the United States in 1866. In the meantime, his mother had been executed for allowing the conspirators to use her boarding house.

Once extradited to America, it proved tougher to convict Surratt than the other conspirators. Unlike the others, Surratt was tried in a civil court rather than a military one, and the jury deadlocked after hearing countless witnesses from the government and the defense. The charges were dropped in 1867, and he was released the following year. In the years that followed, Surratt tried to start a career lecturing about his role in the assassination, but public outrage caused the tour to be canceled after the third lecture. He married, briefly taught, and worked for the Baltimore Steam Packet Company before his death in 1916, at the age of 72.

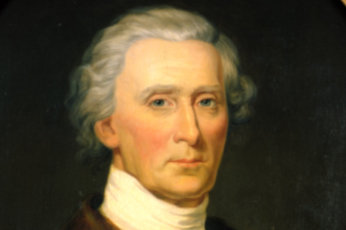

5The Last Signatory Of The Declaration Of Independence

Contrary to what the film National Treasure would have you believe, Charles Carroll wasn’t a freemason and he didn’t leave behind any clues to a secret treasure (as far as we know). But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a fascinating and influential man. Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic signatory of the Declaration of Independence, which he put his name to on behalf of Maryland. Carroll was also the longest lived of the signatories, prompting nationwide mourning when he died in 1832.

The grandson of Charles Carroll the Settler, who had fled the persecution of Catholics in England, Carroll of Carrollton grew up in one of Maryland’s wealthiest families and was estimated to be the richest man in America when the Revolution broke out. Educated at Jesuit schools in France, he became fluent in French and was sent to Canada in 1776 to try and convince the locals to join the fledgling United States. (They declined.)

A consistent supporter of an armed uprising against British rule, Carroll broke ground when he was elected to Maryland’s Convention of 1775, effectively overturning the laws barring Catholics from holding office. He later represented Maryland in the Continental Congress and served in the Senate. Carroll’s service to the country ended with Thomas Jefferson’s election in 1800 and he became the last signatory to the Declaration of Independence after Jefferson and John Adams died on the same day in 1826. He made one last public appearance in 1828, when he laid the cornerstone for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, essentially preparing the country for the coming era of industrialization.

4The Last Mayflower Passenger

When the four-year-old Mary Allerton set sail on board the Mayflower in 1620, she could scarce have imagined that she would be the last surviving pilgrim 79 years later. Mary was born in Leiden in the Netherlands, where her parents had sought refuge from religious persecution in England. In 1620, they decided to depart for the New World.

Early life in America was full of hardships. Mary’s mother died during the first winter, as did many others. Mary herself survived and remained in the Plymouth area for the rest of her life. She married Thomas Cushman in 1636 and raised eight children, of whom seven lived to adulthood. The couple built a prosperous life and would eventually preside over a sprawling clan of some 50 grandchildren.

Beyond her role as a mother and wife and her longevity to 83, much of Mary’s life remains unknown. But she would have been a witness to a tumultuous era in colonial history, living through such dramatic events as King Philip’s War in 1676 and the merger of Plymouth into Massachusetts in 1691.

3The Last Continental Congress Delegate

Naturally, the Continental Congress tended to attract distinguished elder statesmen. As a result, only one delegate made it to the 1840s—John Armstrong Jr. The son of Continental Congress delegate John Armstrong Sr., John Jr. had a distinguished, if slightly tarnished career. His first mistake came at the end of the Revolutionary War, when he wrote the Newburgh Addresses, which called for the army to refuse to disband unless Congress approved higher pensions. George Washington himself had to face down the conspiracy, with the officers only emotionally yielding after Washington produced a pair of glasses, famously declaring: “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray, but almost blind, in the service of my country.”

Armstrong later served as a senator and as ambassador to Paris, where he fell out with Napoleon and resigned at the first chance he got. During the War of 1812, James Madison appointed him Minister of War, with a remit to fix the chaotic military situation. He largely didn’t succeed, failing to support Oliver Perry and William Henry Harrison in favor of a disastrous attempt to seize Montreal. Probably his worst moment came in 1814, when he refused to fortify Washington, believing that a British attack was unlikely. One torched White House later, he was unceremoniously replaced by James Monroe. He retired to a genteel life in the country and died in 1843, the last survivor of the Continental Congress.

2The Last Suffragette

As a young girl, Ruth Dyk marched down the streets of Boston demanding votes for women. She was introduced to the movement by her mother, Annie Belcher, who was one of the first women in America to attend medical school, only for university administrators to force her to drop out after she decided to get married. Her mother’s example made sure Ruth never forgot the value of an education, becoming a distinguished psychologist and authoring three books. From the age of 11, she was active in the movement to eliminate inequality at the polls and remembers her delight when the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920. Ironically, she still wasn’t able to vote that year, since she wasn’t old enough.

Ruth’s mother had once caused a scandal by allowing local prostitutes to stay with her after their house burned down, and Ruth continued her commitment to social justice, working as a social worker for delinquent girls in the 1950s. She also raised three children and finished her anthropologist husband’s seminal book on the Navajo after he developed cancer and Parkinson’s disease at a young age.

Ruth never lost her interest in politics, and her concerned family had to prevent her from campaigning door to door for Hilary Clinton’s 2000 Senate campaign in New York. She continued to work for women’s rights, ruefully noting that the suffragettes hadn’t “changed as much as we hoped for.” She passed away in 2000, at the age of 99. The year before she died, she was able to pay tribute to Annie in a Ken Burns documentary, which opened with her proud declaration: “My mother was suffragette.”

1The Last Of Lewis And Clark’s Companions

In 1807, Sergeant Patrick Gass was the first to publish his story of Lewis and Clark’s epic continental journey. And in 1870, he became the last member of the expedition to die, passing away quietly at the age of 99. A soldier by trade, Gass served as a carpenter on the expedition, building forts, canoes, and wagons. When Lewis and Clark split the expedition into three groups for the journey back from the Pacific, Gass was chosen to lead the third, which skirted around waterfalls on the Missouri River before rejoining Lewis and Clark on the Yellowstone River.

Gass kept a journal on the expedition, but it was barely readable (he had only become literate as an adult). So he brokered a deal with a Pittsburgh bookseller named David McKeehan, who ghostwrote his 1807 account. The book was the first to name the expedition “the Corps of Discovery” and went through several printings, including French and German versions. Since Lewis apparently committed suicide before making any headway into his own memoirs, Gass’s account played a key role in popularizing the expedition with the public.

Sadly, McKeehan got most of the profits and Gass struggled to make ends for the rest of his life. Always patriotic, he reenlisted during the War of 1812 and lost an eye during the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. He later bounced between jobs, getting by on a stingy military pension and regaling his neighbors with stories of his travels. When the Civil War broke out, Gass tried to enlist again at the age of 87 but was turned down. He also led a movement to increase pensions for veterans of the War of 1812, but the army declined to examine his proposals.

When not writing lists, Clarke is living the life of an aspiring historian and writer.

![Top 10 Haunting Images Of Historic Tragedies [DISTURBING] Top 10 Haunting Images Of Historic Tragedies [DISTURBING]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/33758v-150x150.jpg)