Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Greatest Successful Bluffs In History

Winning a battle or moving valuable cargo around the world is no easy task. To be successful, sometimes you have to get creative and deceive your adversary. Often, the best strategy is to trick your opponent into underestimating you or to otherwise employ shifty subterfuge.

10 Operation Anadyr

The Russians practice military deceit and denial so often that they have a specific term to describe the strategy: maskirovka. It was the basis for Soviet plans during the Cuban Missile Crisis (or what the Russians call the “Caribbean Crisis”). Top-level Soviets trusted no one, so they designed their bluff to fool everyone, including the Soviet military. Khrushchev and the Soviet state apparatus planned to deceive the Americans (and their own troops) about their true intentions regarding the large-scale movement of troops and weapons. Then they intended to vehemently deny reality when everyone wised up. The plan was code-named “Operation Anadyr.”

Anadyr is a frigid river that flows into the Bering Sea, and it was the location that the Soviet high command “chose” for military exercises. Missile engineers were erroneously informed that they would be going to a nearby island, Novaya Zemlya, to test ICBMs. The Soviets provided all of their intelligence and soldiers with winter outfits, skis, and parkas, even though they were heading to Cuba. To further keep up the ruse, troops were only moved at night.

The Soviets wanted the American intelligence and any Western spies to think that the missiles were being moved north rather than to the coast of Florida. As a way to deploy ground forces to Cuba, the Soviet high command pretended that they were moving four regiments from the Siberian nuclear location to Cuba to make room for incoming regiments that were part of Operation Anadyr.

The operation went smoothly, and the Soviets were able to get their ICBMs close to Cuba before JFK found out. Even after U2 footage revealed Russian troop movement and suspicious-looking objects, Khrushchev outright lied to the president of the United States. When Kennedy began to suspect foul play, Khrushchev sent JFK a personal telegram saying that “under no circumstances would surface-to-surface missiles be sent to Cuba.” What followed next was the closest the world ever came to World War III as Kennedy figured out just how to call the communists’ bluff.

9 Tube Alloys

The Manhattan Project is a well-known part of World War II history. Everyone knows about Los Alamos and Robert Oppenheimer, but the British are mostly left out of the narrative.

The initial stages of atomic development saw incredible Anglo-American cooperation. However, it was the British who really jump-started research and development of an atomic weapon with the fission experiments of O.R. Frisch and R.E. Peierls at Birmingham University in 1939–40. Actually, this isn’t surprising because the Americans had not yet entered the war. But the British were never fully integrated with official members of the Manhattan Project. So in 1942, they began their own covert atomic program.

The British knew the magnitude of the project, and they, like the Americans, wanted to keep it out of unfriendly hands. Neither the Nazis nor the Soviets were to know about the projects. But Britain went about it a bit differently than the Yanks, employing their characteristic droll and dry British humor to work their deception. As a result, their atomic program had much less security and secrecy than did the Manhattan project because the British simply used the most boring name possible. They called their project “Tube Alloys” so that no one would think to look too closely. Their deception worked.

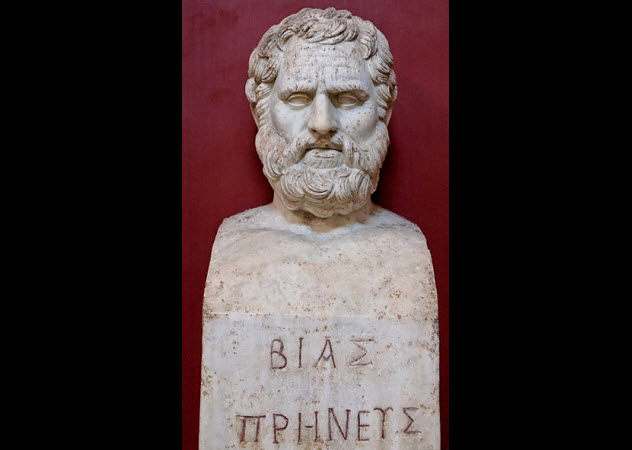

8 Bias Of Priene

This story comes from ancient biographer Diogenes Laertius’s history of Greek philosophy, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Written in the third century AD, the book chronicles the siege of Priene from the sixth century BC (which, of course, means that the story should be taken with a grain of salt).

Bias of Priene was one of the seven sages of Greece, and he led the city against the invading Lydian forces of King Alyattes. The king was doing quite well in the war and had the starving city of Priene on its knees, almost ready to surrender. But Bias came up with a clever plan to trick Alyattes. Even though the city was starving, he fattened up two donkeys and sent them with two healthy men to Alyattes’s camp. The ruse convinced Alyattes that the whole of Priene was also in such good condition and that the city had plenty of supplies to outlast his already long siege.

7 John B. Magruder

In 1862, Confederate General John B. Magruder needed to hold off Union Major General George B. McClellan’s advance on Richmond until reinforcements could arrive. The biggest problem with this plan, however, was that Magruder only had about 14,000 soldiers while McClellan had about 55,000. There seemed to be little hope for the Confederates until Magruder decided that he could stem the Yankee advance with a bit of theater.

Magruder used the Warwick River to fool the Union Army into thinking that his forces were far superior to what they actually were. When the river stopped the Union forces, they found the confederates well garrisoned along its 23-kilometer (14 mi) length. Erasmus Keyes, the officer in charge of McClellan’s left flank, witnessed columns of gray uniforms flowing beyond the trees. He heard thundering drumrolls and the commotion of soldiers cheering as they fell into position.

This, of course, was all an illusion cooked up by Magruder. He did line his men along the length of the river but their position was not strong at all. He barely had enough men to make them stretch end-to-end. To maintain the look of disciplined troop movement, he used the same column of men over and over. They simply doubled back after they put on enough of a show to convince the Union soldiers that they were fortified and ready for a fight.

After Keyes reported to McClellan about the formidable Confederate force they were about to face, McClellan chose to lay siege to the nearby city of Yorktown rather than press on to Richmond. In the meantime, Magruder and his men were able to escape with minimal casualties, and reinforcements arrived in the city.

6 Doug Hegdahl

Doug Hegdahl was only 19 when he decided to go above deck on the USS Canberra to watch the ship’s nighttime bombardment of the North Vietnamese forces. This turned out to be an awful idea because the force of one of the guns knocked him overboard into the Gulf of Tonkin. It was 1967, and the young Navy man found himself literally floating in the middle of the Vietnam War. He tried to swim to safety, but the Viet Cong found him first. Doug soon became a guest at the Hanoi Hilton.

At first, the Vietnamese refused to believe Doug’s story about being blown off the deck of his own ship. They assumed he was a spy. After repeated interrogations, however, the Vietnamese changed their minds, convinced that they had only captured a simpleminded fool who was not a threat. As a result, they allowed him greater freedom to roam the POW camp than they did with more valuable aviators and officers.

In reality, Doug was exceptionally brilliant (barring his bad judgment to go topside during a firefight). He maintained the illusion of being mentally challenged so that he could move around the camp without much supervision and collect vital information. Using his incredible power of recall, Doug memorized the names of all the prisoners as well as the names of their parents and hometowns. When the senior POWs in the prison realized Doug’s potential, they ensured his release. Doug was able to provide the US with confirmation on the MIA status of soldiers and officers. This gave the US incredible leverage with the Vietnamese, who had not been releasing any information about the number of POWs they had or who was alive or dead.

5 Washington’s Evacuation Of Long Island

The first major battle of the American Revolution did not go well for the colonists. Washington needed to defend the critical city of New York from a rapidly advancing British Army.

At the Battle of Long Island, the Brits handily outflanked Washington and captured roughly 1,000 of his soldiers. Washington recognized that the best course of action was to save his army to fight another day. It would have been foolish to attack the larger and better-prepared British Army. He needed a full tactical retreat, but executing one was difficult. Timing had to be perfect, with regiments arrayed in a manner that did not leave their front exposed.

To carry out the evacuation flawlessly, Washington made it seem like the opposite was happening. He had all the ships placed as if they were going to ferry in reinforcements rather than evacuate the original soldiers. This ensured that the troops would not panic and rush the ships when they learned that they were evacuating. It also appeared to the British that the Americans were actually going to stay and fight. Remarkably, the Continental Army executed the whole affair with complete secrecy. Even Washington’s officers were fooled. The soldiers thought they were preparing for a suicide attack. But then, aided by the weather, they began to successfully retreat.

4 Regiomontanus’s Almanac

Christopher Columbus did not have the best relationship with the native peoples of the places he “discovered.” There may have been initial periods of peace fostered by the wonder factor of new cultures interacting, but that goodwill only went so far.

In 1502, Columbus was stranded on the north coast of Jamaica. His crew decided that the best way to get help was through plundering the local villages. Of course, the natives responded with hostility, forcing Columbus to figure out a way to stave them off before they killed him and his outnumbered crew.

Gambling, Columbus bluffed to the natives, telling them that if they did not help him out, the Moon would disappear. He had a copy of Regiomontanus’s almanac, the Ephemerides, that showed that a lunar eclipse would happen in Nuremberg, Germany. But Columbus had no way of knowing if an eclipse would happen in Jamaica, expecially with the time lost at his new coordinates.

Fortunately for Columbus, he had witnessed other lunar eclipses on his voyages, so he was able to figure out the discrepancies with the almanac and successfully predict the eclipse. The natives were frightened enough to give Columbus the time he needed to fix his ship.

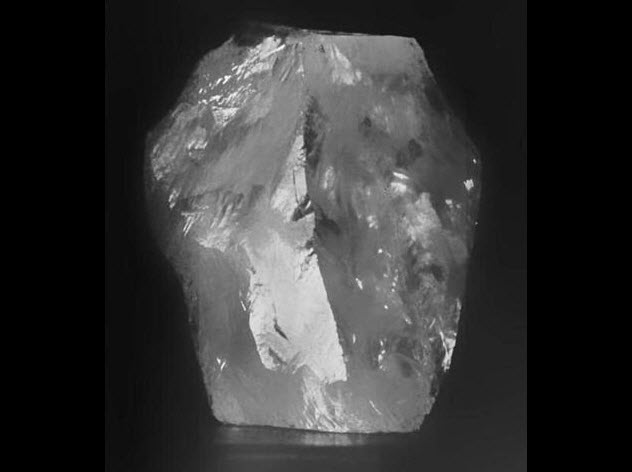

3 Cullinan Diamond

In 1905 in South Africa, Captain Frederick Wells discovered the Cullinan diamond (aka the “Great Star of Africa”). At the time, it was the largest diamond ever discovered, and it would not be surpassed until the 1985 discovery of the Golden Jubilee Diamond. Interestingly, both diamonds were found in the same mine.

In the early 1900s, South Africa was a colony of Britain, so the South Africa Prime Minister Louis Botha decided to give the diamond to King Edward VII. It was a deeply symbolic gesture because South Africa and Britain had just fought the bloody Boer War. In addition, Louis Botha was an Afrikaner war hero who had led a bloody guerilla campaign against the British. He felt that it was absolutely necessary to present such a huge token of goodwill after the war. The biggest problem, however, was how to ensure the diamond’s safe arrival in Britain.

The South African government decided to send the diamond under armed guard in a great procession on a massive steamboat. Great fanfare accompanied the diamond on its ocean journey, but the stone on the ship was a fake. The entire shipping process was a ruse. South Africa wanted to divert attention from how they actually sent it: by post. They simply wrapped the diamond up and sent it by mail. Everyone was fooled until it reached the king.

2 Battle Of Megiddo

In World War I, the Allied fight against the Ottomans had been a bloody back and forth for much of the war. It was mostly British and Anzac troops fighting in disease-infested wet areas. The most famous fight was the Gallipoli campaign, which did not go well for the Allied Powers. But as the war reached its end, the Brits began to achieve some decisive victories.

In 1918, the Battle of Megiddo was one of the most decisive victories of the campaign, and it involved some clever tactics concocted by Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund Allenby. He wanted to attack the Ottoman front lines at the Plain of Sharon near the coast. It was ideal territory for that glorious cavalry charge that the Brits had wanted for the entire war.

To achieve maximum success, the Brits began to divert Ottoman attention away from the real location of the attack. British forces built an entire fake camp deep in the interior of Palestine, complete with dummy horses and increased patrols of real men. They also made sure to light giant fires at night to fool the Ottomans. It worked, and the Brits successfully defeated the Ottomans on the coast rather than on the Jordanian border.

1 The Battle Of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was a significant battle in the Southern theater of the American Revolution. The fighting saw the young, battle-hardened British officer Banastre Tarleton face off against the older American officer Daniel Morgan. It was 1781, and the war in the Southern theater had not been going as the British had wanted. It was supposed to be a loyalist stronghold, but revolutionaries filled the backcountry. General Cornwallis was furious with the state of affairs, and he sent Tarleton in pursuit of Morgan through rural South Carolina.

Although both officers commanded roughly the same number of men, Tarleton’s entire army consisted of professional soldiers. Morgan’s men were mostly untrained militiamen who had proven that they would break easily in front of an organized British assault. Morgan knew that Tarleton was aware of that weakness, so Morgan brilliantly anticipated Tarleton’s maneuvers.

Instead of trying to get his mostly untrained men to hold the line against the better-equipped British, Morgan decided to have his men fire two volleys and then fall back. It would appear as if they were retreating. But Morgan ensured that his position was between two rivers and that his men would have to stand and fight eventually. To guarantee that it would not be a slaughter, Morgan placed his well-trained regulars and sharpshooters on a ridge where they could fire directly into the advancing British Army. Lastly, he engineered the situation so that his militia could link with the Patriot cavalry and fully envelop the remaining British.

The battle was over in less than an hour. It was a complete rout and an enormous victory for the Americans.

I’m a graduate student of British history, and I like to write articles in my free time. Check out my other work here at Listverse or my work over at Cracked.com