Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Reasons Hitler Hosted The Craziest Olympics Of All Time

The 11th Olympic Games of the modern era was held in Berlin in 1936. It would go down in history as the “Nazi Games,” a vehicle of unabashed self-promotion for Adolf Hitler and his regime. The Nazis had hoped the Games would provide a clear demonstration of Aryan superiority and a vindication of their doctrine of the master race. Never before had politics intruded so brazenly into sports, making for a very interesting and controversial Olympics.

10The Counter-Olympics

As Berlin prepared to host the 1936 Olympics, many people were already suspicious of Nazi ideology and agenda. Sports insiders were particularly disturbed by reports of persecution of Jewish athletes. Many within the Olympic organization felt that participating in the coming Games was tantamount to showing support of the Nazi regime. Calls for boycott began to be heard. The debate was particularly intense in the United States, which traditionally fielded the largest team in the Olympics.

Other countries also had groups opposed to the Games. The new republic of Spain went beyond plans for a boycott and proposed an anti-Nazi counter-Olympics to be held in Barcelona, the city that lost out to Berlin in the 1931 vote for the host city. Barcelona had been greatly disappointed at the decision, believing that it was well prepared to hold the Games. Barcelona already had new, modern facilities used in the 1929 International Exposition, plus the Hotel Olimpico that could house the athletes.

Spain was determined to take the glory away from Hitler and the Nazi propaganda machine. Invitations to the “People’s Olympics” were sent out and answered by radical and left-wing athletes from around the world, including the US. There were German athletes who joined to protest the regime at home. Communists, socialists, anarchists—Barcelona swarmed with players of every leftist stripe, 6,000 athletes from 22 countries in all. To call out Nazi bigotry and racism, the emblem of the People’s Olympics depicted three muscled athletes: one white, one black, and the last of mixed ethnicity. The warm and fraternal atmosphere in Barcelona was evident.

But then, just 24 hours before the opening ceremony, the fascist General Francisco Franco launched the military revolt against the government. The Spanish Civil War had begun, in which Hitler would support Franco and the Nationalists. The People’s Olympics was canceled. Nevertheless, individual players had spoken out their conscience and shamed the Nazis. Eventually, Spain and the USSR would be the only countries to boycott Berlin. Barcelona got the chance to host an Olympic party—legitimate this time—in 1992.

9The Nazi Origins Of The Torch Relay

No moment better defines the modern Olympics than the torch relay, a moving symbol of international brotherhood and cooperation. From the lighting of the sacred flame in Olympia, Greece, to its spectacular entrance into the stadium, it cannot fail to excite and electrify. That’s what German Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wanted spectators to experience—not for brotherhood but for the glory of the Nazi regime.

Not many people know that the torch relay is a Nazi invention. The ancient Greeks did run relay races that involved flames as part of their worship to the gods. But all the modern Games before Berlin did not have a torch relay. The idea was not actually Goebbels’s. It was proposed by Carl Diem, secretary general of the Games’ organizing committee and inspired by the flame that burned at the Amsterdam Olympiad in 1928. Goebbels decided to squeeze the last drop of propaganda mileage out of the torch relay, which satisfied Nazi thirst for spectacle and ceremony.

At the lighting ceremony in Greece, the flame was dedicated to Hitler as the band played the Nazi anthem Die Fahne Hoch. By depicting the relay as an ancient tradition, the Nazis were proclaiming themselves heirs of civilization’s progress from Greece, to Rome, and finally to Germany. The torch’s 2,500-kilometer (1,500 mi) route to Berlin passed through Czechoslovakia, where it provoked a clash between ethnic Germans and Czechs. On the last stage of the relay, only blond and blue-eyed athletes were allowed to bear the torch.

Just as Goebbels had hoped, the stirring sight of the flame being carried into the stadium by a fine specimen of Aryan manhood impressed spectators into concluding that the Nazis were strong but not brutal. The New York Times reported that Germany showed “goodwill” and “flawless hospitality.” The Associated Press assured its readers that the Games betokened peace in Europe.

The hollowness of Nazi propaganda was revealed by the catastrophic war years. Nevertheless, at the resumption of the Olympics in London in 1948, the torch relay was retained with a brighter message of friendship and peace. It still remains a symbol of goodwill, one legacy of Nazism we decided was worth keeping.

8Pigeons Poop On Der Fuhrer’s Show

The opening ceremony was a dazzling display of German power. Hitler’s motorcade bore down avenues bedecked with swastikas to the Olympic stadium. In the skies above Berlin, the airship Hindenburg majestically swept the clouds. The Fuhrer and the Nazi hierarchy proceeded down the steps into the arena, to the screams of the delirious and worshipful crowd of 100,000. Here were the gods of the new Olympus. It was Hitler’s day, his moment of glorification. But it seemed the birds had other ideas.

Louis Zamperini, a runner in the US Olympic team, recalled the Chaplinesque moment worthy of Hitler’s mustache when thousands pigeons were released. “And then they shot a cannon and (it) scared the poop out of the pigeons. Literally scared the poop out of them. And we had straw hats and you could hear the pitter-patter on our hats. I mean it was a mass of droppings and it was so funny.” With typical American bravado, Zamperini would later steal the swastika flag hanging outside Hitler’s office building, the Reich Chancellery, outrunning the guards and keeping the flag as a souvenir.

There were other comedies of error. The New Zealand team mistook a German standing erect in front and to the left of Hitler’s dais for the Fuhrer himself and removed their hats to this imposing figure. They then put them on again as they passed Hitler. The spectators apparently misread the French team’s Olympic salute (right arm thrust out sideways) as the Nazi salute (arm out front) and cheered their traditional enemy in genuine approbation. Of all the national teams, only the US refused to lower their flags to Hitler, and an official statement explained the controversial failure to dip the flag as a matter of army regulations.

Another embarrassing incident during the first day involved Liechtenstein and Haiti. Like someone at a party discovering another wearing a similar dress, the Liechtenstein team was surprised that the national flag of Haiti was of the same blue and red pattern as Liechtenstein’s. This spelled potential mix-up in the medal ceremonies. Fortunately, Haiti’s only athlete withdrew, and Liechtenstein didn’t win any medals. To prevent future confusion, Liechtenstein added a crown to its flag a year later.

7The First Televised Games

The 1936 Berlin Olympics was the world’s first televised sporting event. The games were broadcast by the German firms Telefunken and Fernseh. Twenty-one cameras, three of which were the 2-meter-long (6 ft) Fernsehkanonen (“television cannon”), provided live transmission over a 72-hour period to special viewing booths called “Public Television Offices” in Berlin and Potsdam. Around Berlin, 150,000 people crowded into the 28 viewing rooms.

The primitive RCA and Farnsworth equipment produced only fuzzy black-and-white images. But in 1936, it was significant progress from following games via radio, which was how sports fans tuned in since 1921, when Pittsburgh’s KDKA began broadcasting boxing, later followed by baseball and football. It was also a German technological coup that it had beaten the US in the TV race. The Germans conveniently ignored that they were using a technology pioneered by Vladimir Zworykin, a Russian Jew, and Philo Farnsworth, a Mormon—two men whose ethnic and religious backgrounds would have earned them the contempt of the Nazis.

The Germans knew they were engineering the future. The program guide Television In Germany concludes: “From these initial stages of television in broadcasting and telephony, there is a growing up a cultural development that promises to be of unsuspected importance to the progress of mankind.”

America did have one consolation. The first broadcast showed Jesse Owens winning the 100-meter final. It was ironic that German technology would show the African-American Owens stomping on the notion of Aryan superiority.

6Jesse Owens And His Nazi Shoes

Jesse Owens won four golds in Berlin, for the 100 meters, 200 meters, long jump, and 4×100 meter relay. He was the acknowledged superstar of the Olympics. What is less known is that he got a little help from a member of the Nazi Party named Adolf “Adi” Dassler, a shoemaker whose company, Gebruder Dassler Schuhfabrik, specialized in track and field footwear. Dassler came to the Olympic Village with the intention of having as many athletes as possible wear his shoes. Dassler did not have the marketing and advertising tools to promote his brand, so everything had to be done by word of mouth.

Dassler approached his friend and the coach of the German track team, Jo Waitzer, who supported his endeavor to design running shoes that would improve the performance of track athletes. Waitzer agreed to persuade the runners even from other national teams to try out the shoes. Having read about Owens’s performances in the Olympic trials, Dassler was particularly interested in getting the shoes on the American’s agile feet. Dassler urged Waitzer to hand out some shoes to Owens. The coach was hesitant, as he knew his life could be put in danger if the authorities ever found out he was in contact with the African-American star.

Nevertheless, Waitzer braved the risk and smuggled two or three pairs to Owens, all personally crafted by Adi himself. They were made of glove leather, reinforced at the heels and toes with six track spikes. It was pretty much state-of-the-art at the time. Owens won the 100 meters in his German shoes, and by the third pair, Owens said he wanted only those shoes or none at all. He became the unwitting first pitchman for the product.

Berlin was soon abuzz that the impressive black American had accomplished his record-setting feats in shoes made in the small German village of Herzogenaurach. Dassler’s sales skyrocketed. It was worldwide prominence after that for the shoe company everyone knows today from Adi Dassler’s name—Adidas.

5The Dirtiest Basketball Final

Berlin showcased the first-ever Olympic basketball competition. Dr. James Naismith, the game’s inventor, received the honor of tossing the ball for the tip-off of the very first game, Estonia vs. France. The USA was the clear favorite, being the sport’s country of origin, and true to expectations, they steamrolled the opposition effortlessly before facing Canada in the finals.

Basketball was meant to be an indoor game, but the German organizers were unfamiliar with basketball (Germany had no basketball team) and failed to provide indoor facilities. Instead, the games were played outdoors on a clay tennis court, where goals with wooden backboards had been installed. The players had to make do with a ball that was bigger and heavier than today’s. There was a slit on one side for the bladder, so the ball wasn’t perfectly round. This made dribbling on the clay difficult, even in dry conditions.

The day before the final, there was a torrential downpour, turning the court into a muddy mess. The Germans wanted to get the game over with and did not call a postponement as the rains continued the next day. Americans squared off with Canadians in the dirt surrounded by 500 spectators. Dribbling was now well-nigh impossible, and the ball was moved up the court chiefly by passing. The slippery court substantially slowed down the game. The German referees, who didn’t speak English, officiated atrociously.

In the midst of these difficult conditions, the score only stood at 14–4 by halftime of the 40-minute regulation period. The US inflicted a crushing 19–8 victory on Canada at the end.

4Hitler’s Football Embarrassment

Adolf Hitler was never a football fan. He believed that building up a physically fit German youth could be better accomplished by sports like boxing and athletics. But the Nazis did support a strong football team that could play a part in the propaganda machine. They organized clubs and encouraged people to play. Football was also the most popular sport and guaranteed to make the Nazis money.

Team manager Otto Nerz made the Germans a powerful football team, and in 1936, it was joint favorite with Great Britain. The first match was a devastating 9–0 triumph over Luxembourg, a spectacle so overwhelming that the officials decided to invite Hitler to the next match against Norway. Hitler had never been to a football game before, but surely he would not want to miss his Aryan superstars dominating the opposition, whom they had defeated in their last eight meetings. This one should be a breeze.

Hitler gave in to his underlings and, with 55,000 other spectators, took his place at the Poststadion, preparing to savor the sweet victory of his Wunderteam. The Germans did not disappoint in the early minutes—the Norwegians hardly made it past the half-line. But then, the Germans began bungling their chances. Norway found an opening and crashed through with the first goal. Hitler was agitated and began to explode in a tantrum. The Germans doubled on the attack, with Nerz ordering the defenders into the action. But another Norwegian shot sailed past the goalie. Hitler had seen enough. He rose up in an uncontrollable rage and left his first and only football game in a huff. The score was 2–0 for Norway at the final whistle.

3Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia

The 1936 Games came to be immortalized on film, using pioneering moviemaking techniques that changed cinema forever. The monumental masterpiece was Olympia, directed by Leni Riefenstahl. Unlike the blatant celebration of Nazi power in her earlier Triumph of the Will, Riefenstahl’s heroes in Olympia were those who genuinely excelled, regardless of nationality or race. Aside from spectacle, Riefenstahl emphasized the beauty of the human form. To accomplish this, she manipulated the camera lens in ways never done before.

Riefenstahl was one of the first to use a moving camera for traveling shots in a documentary, putting her crew on roller skates as they took the footage. She built a track so the camera could move alongside the sprinters. She had a pit dug so she could film the pole vault against the backdrop of the sky. Riefenstahl developed a special 600-mm telephoto lens for close-ups and compact shots and sent aloft a balloon with a small 5-mm camera for aerial views. An underwater camera that changed speed and focus skillfully managed the tempo of the different diving events.

Riefenstahl edited the shots for maximum dramatic impact. The transition shots from one event to the next were wonderfully fluid. Close-ups captured the sweat and strain of marathon runners, their exhaustion and determination to go on. This was interspersed with crowd reaction shots with synchronized background music giving the athletes’ movements the impression of a dance. This was back in the days when to simply attach any sound to film was difficult. But Riefenstahl did it with impressive precision that stunned audiences. Never before had a documentary been produced with editing and sound.

There is controversy over whether Olympia was overt propaganda or not. On one hand, Goebbels clearly was involved in the film. On the other hand, Riefenstahl featured African Americans Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalf, whose successes Hitler clearly resented. She was also not averse to recording German defeats at the hands of other competitors. Later on, Riefenstahl left overtly Nazi footage on the cutting room floor. Nevertheless, the Nazis used the feel-good and inspirational theme of Olympia to reflect back on the regime.

Olympia won the grand prize at the 1938 International Film Festival in Venice, beating Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Disney himself welcomed Riefenstahl to Hollywood with open arms, the only studio executive to do so in the wake of Kristallnacht. Even today, Olympia‘s brilliant cinematography continues to mesmerize.

2Art As Sport

Once upon a time, the Olympics awarded medals for art. It was founder Pierre de Coubertin’s vision that the Games should highlight aesthetics as well as athletics. Every Olympics between 1912 and 1948 awarded gold, silver, and bronze in five categories: architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, and music. All works had to be sports-themed—paintings, for example, could feature athletes in action, while musical pieces might pay homage to a sport or an individual competitor. The German Art Committee proposed to add a Works for the Screen category for 1936, but de Coubertin apparently smelled a rat and turned it down, sensing that it would be a vehicle for purely propaganda films.

In Berlin, the Germans dominated the art competition jury, taking liberties with home court advantage to remedy the situation that saw Germany haul in just one medal in the last two Olympics. Remedy it did—German artists won five out of the nine medals handed out. German musicians made a clean sweep of the Musical Composition Solo and Chorus categories. The only American to win a medal was Charles Downing Lay, with his Architecture entry “Marine Park in Brooklyn.”

Initially, the public showed no enthusiasm for the art competition. But a flurry of propaganda eventually interested 70,000 people to view the exhibition, making it one of the most successful Olympic art competitions. We can only speculate how much money the Nazis raked in from the sales of the artworks, as transactions were made “without the usual formalities,” according to the official report. To the delight of de Coubertin, however, the award-winning musical compositions were played by the Berlin Philharmonic in a concert at the end of the Games.

The amateurism clause of the Olympics eventually killed the art competition. The quality of the entries never seemed to satisfy the jury of art critics, and it became the practice to withhold medals and proclaim no winner. It was discontinued after the 1948 London Olympics.

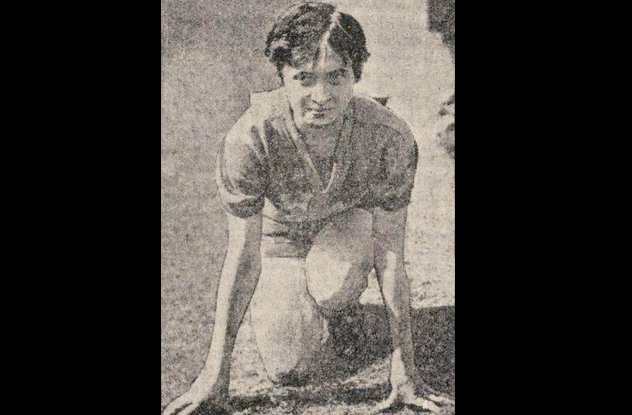

1Elizabeth Robinson’s Unbelievable Comeback

Elizabeth Robinson’s gold in 1936 came five years after she was given up for dead, her battered body taken to a mortician for burial.

Betty was a native of the Chicago suburb of Riverdale and attended Thornton Township High School. One day in 1928, her biology teacher spotted her chasing a commuter train and was astonished at her speed as she caught up with it. After timing her later as she ran 50 meters (150 ft) down the school corridor, the teacher encouraged Betty to join the Illinois Women’s Athletic Club. Soon, Betty was clocking near-record times at competitive events. In July, she passed the trials and made it to the 1928 Olympics US team.

At 16, having never been away from home, Betty was on a ship to Europe. This was the first time female athletes were allowed in track and field events, over the objections of Baron de Coubertin and Pope Pius XI. In Amsterdam, Betty became the first woman—and the youngest—to win the gold in the 100 meters, setting a world record of 12.2 seconds. She returned to the US a heroine and continued to break records thereafter.

Then, on a hot June day in 1931, tragedy struck. Betty was with her cousin Wilson Palmer in a biplane 200 meters (600 ft) up when the plane stalled and nosedived. The horrific impact left both unconscious. The man who pulled Betty from the debris saw her mangled body and bloody face and thought he was looking at a corpse. He put her in the trunk of his car to a nursing home and left her with the undertaker there. Fortunately, the undertaker noticed she was still alive, and she was taken to the emergency room.

Betty drifted in and out of consciousness for 11 weeks while she was in the hospital. Doctors repaired her damaged left leg by inserting a rod and pins to stabilize it. Doctors feared Betty would never walk again. The media proclaimed her running days over. Betty’s left leg became half an inch shorter than the right. She was in a wheelchair for four months. It was a crushing blow for Betty, who wanted to defend her 100-meter title at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics.

But with grim determination, Betty struggled to walk then run again. By 1934, she was back in training. She missed LA, but was ready for Berlin as a member of the 4×100 relay team. Since Betty’s shortened leg made her unable to start in the crouch position, she was allowed to start standing up. Betty ran the third leg, handing over her baton as the favored German team fumbled and dropped theirs. The Americans surged forward, giving Betty Robinson her improbable second Olympic gold. The International Olympic Committee called her comeback “one of the most remarkable in the annals of the Games.”

Betty retired from competition soon after and married Richard Schwartz in 1939. She continued as a coach and gave talks to athletic associations across the US. Elizabeth Robinson Schwartz died in 1999, an almost forgotten Olympic heroine.

+The Muslim Women Who Snubbed Hitler

Halet Cambel personified the new Turkish woman in the 1930s. She exemplified the transformation of Muslim Turkey into a modern secular state led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, where women received the same rights and opportunities as men.

Cambel was born in Berlin to a family with close connections to Kemal. She was a sickly child, falling prey to typhoid and then to hepatitis. Cambel got herself into shape with exercise. She was fascinated by stories of knights, which led her to take up fencing under a Russian coach. She returned to Istanbul in 1924 to study archaeology, but her fencing skills earned her a place in the 1936 Turkish Olympic team with fellow fencer Suat Fetgeri Aseni Tari. They were the first Turkish women to compete in the Games. Cambel was repulsed by Nazi ideology and did not want to go, but the Turkish government prodded her to participate. Her disgust toward Hitler must have been heightened when she saw the Fuhrer’s infuriated reaction to Jesse Owens’s victory.

Cambel and Tari did not win any medals, but they will be remembered as the women who defied Hitler. Cambel recalled the moment: “Our assigned German official asked us to meet Hitler. We actually would not have come to Germany at all if it were down to us, as we did not approve of Hitler’s regime. We said that we would never have come to Berlin if our government had not told us to do so. When the official asked us to go up and introduce ourselves to Hitler, we firmly rejected her offer.”

Halet Cambel settled down to life as an archaeologist after the Olympics.

Larry is a freelance writer whose main interest is history.